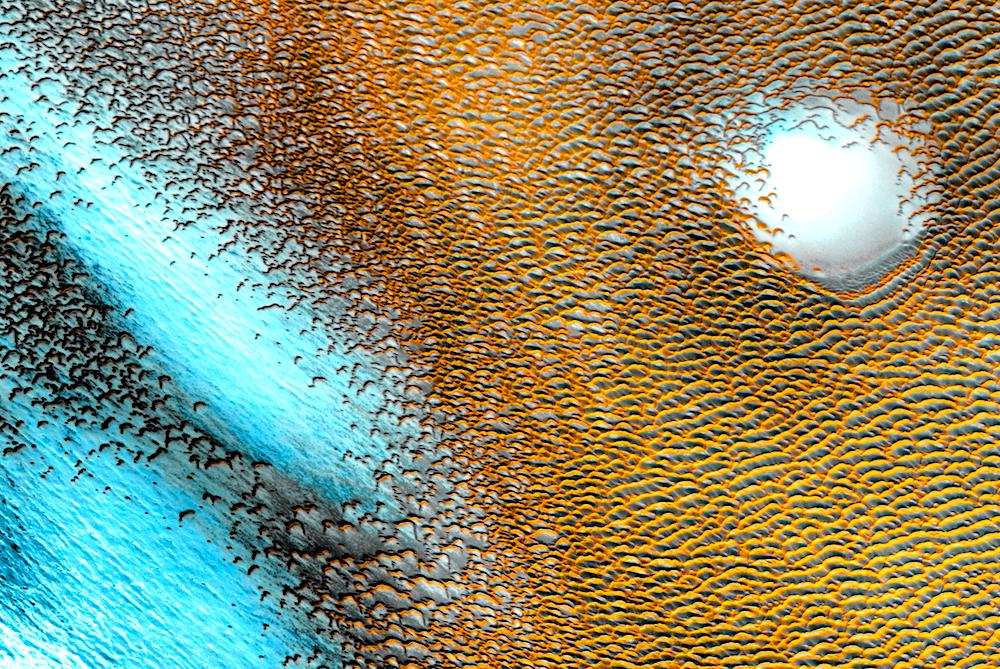

Photo courtesy of NASA's image library

One of my fondest childhood days was spent at Steve Martin's house—not the famous comedian but another Steve Martin, the coolest boy at Mount Pleasant Elementary, 1969. He had an impossibly wide smile, a paisley shirt and bell-bottoms jeans. I had never been to a boy's house before. Only girls liked me, because I was girlish. And because girls didn't invite boys to their homes, this was my first time ever going inside another family's world.

My mom drove me over Saturday morning.

"Ooo," she said, looking at the three story home from an earlier century, "they're rich. I didn't dress for this."

"You don't need to come in," I said, running off with speedy seven-year-old feet.

She stuck her long neck out the car window and stage-whispered, "Behave!"

I knocked on the door—it had its own gargoyle knocker! Steve opened it, a finger to his lips, a shush-command in his glare. I tiptoed silently after him.

I remember his older brother lolling on the couch, a cereal bowl on his lap, watching cartoons, ignoring me.

Steve and I sat and watched, too.

I remember an older sister, who was a cool teenager. She especially liked me—we played that I was her butler. She fixed my hair and dressed me in a cool outfit—which she let me take home.

I got to meet the whole family. They were glamorous. The parents looked like movie stars—ones on vacation. The kids did the cooking. Wild!

The mom kept telling me to help myself to pop and made sure the other kids were being hospitable to their guest.

I don't remember much else: the gloss of the fashion magazine the teenage sister and I read together; the mother yelling "bowls!" and the brothers grumbling back into the living room to fetch their drying cereal remains; the father joking with me that the hamburgers we were having for dinner were made from horse—neigh!

My school days as a little gay boy at the dawning of the Canadian '70s were not collegial. I was avoided on good days and mocked or abused on bad ones, so Saturday-at-the-Martin's was a lovely change. I think the main thing I took from it was that rich people were classy on the outside but messy and chaotic on the inside, in a fun way.

Fifty years later, I was looking after my mom, who was dying from DLB—Dementia-with-Lewy-Bodies—when Steve Martin, the comedian, came on the television in her little retirement apartment.

"Hey!" I said to her standing behind her easy chair, brushing her wispy hair, "Remember Mount Pleasant Elementary School's Steve Martin? From when we lived in Quebec?

"The boy who was mean to you."

"No, no," I said, coming around the front, between her and the TV, hauling out the gentle voice I used to correct her delusions. "He was my friend, remember. I went to his house to play."

"I remember," she said, craning her neck to see around me, her wrinkles pulled taut, eyes focused and purposeful—suddenly once again my young '70s mom, waving her anxious boy aside. Behave.

I stepped aside as a chill rippled through me. She tipped herself back upright and continued, "The teachers arranged it. They thought it would stop him from tormenting you."

I've been floored several times in my life, but never quite like that. I couldn't speak. I plopped onto the orange flowery couch—the sofa bed we'd had in the basement for decades for company, now my spot in the living room and my bedroom at night. I bit into my finger as the ramifications continued to wriggle into my mind and body. The movie, Roxanne, played on, and my mother, oblivious to what she'd just done, fell asleep. In her dotage, she had forgotten to maintain the decades' old benevolent lie.

Flickers of beloved memories came to me but then turned in the new light, revealing other interpretations. The older brother wasn't indifferent to me. He'd sneered when I came into the Martins' living room, stretching his feet out, pulling the bowl up onto his belly so I couldn't sit beside him on the couch.

Steve had cereal, too. The brothers refilled several times, a family size box of Fruit Loops—a sugary cereal my mom would never have let my sister and I have. Neither offered to get me any. The clink of spoons was louder than Casper with the volume down.

I remember now: we were having to be quiet because the parents were sleeping in. The Parents!

And I met the sister because Steve took me upstairs to play in his room and said, "I'll be right back." He never returned. Eventually, maybe hours later, I had to go to the bathroom. I ventured out into the hall and stood trying to guess the correct door. I was terrified I'd open the master bedroom, but I heard a snore tumble down a higher staircase and remembered the house had three floors. I guessed this floor's bathroom was the purple door (all our doors were white) not the blue one or the green one. But, purple was the teenage girl's room, and I woke her. She had me go downstairs and bring us up chocolate milk for lunch on a tray with magazines from the hall table. It was my punishment for waking her.

And the cool clothes I was gifted? They were the older brother's hand-me-downs that Steve had rejected. The sister had pulled them out of a garbage bag on its way to the charity shop.

And when the father had said our meal was horse meat, they all looked at me. The older brother said, "She's gonna cry." And the whole family laughed, which is when I noticed how wide all their faces were. Long teethrows. Like a TV commercial for something American.

When I came back into the present, an American commercial was on in my mother's apartment—only for denture cleaner, not toothpaste. When Daryl Hannah's blonde curls flooded back on screen, I turned the TV off. I didn't want to see more of Steve Martin's virtuous deceit. My mom's innocent snore calmed the room like a warm cat's purr.

And now I have two childhood days. I remember them both, because the innocent, edited version is still in circulation. Sometimes recalling one memory will trigger the other—that time the Martin family enjoyed my charming visit, and that other time the Martin family was forced to endure the school weirdo for a day. But just as often, it's one on my mind alone when Steve Martin comes on TV, or when I read that IKEA is accused of using horse meat, or when a teenage girl in my vicinity lazily flips a page of a fashion magazine and either she rolls her eyes or smiles my way.

Subsequently, there are two of me, two children I have been: the adorable poor ward of that lucky rich family and the unlovable little queer foisted upon a normal family's Saturday.

I wouldn't have this double childhood if my mother had only remembered to prolong the deceit. She is double, too: the wrinkly, sleepy, wispy, delusional ancient who is dissolving day by day, and the sassy, conspiratorial '70s mom, engineering my sense of the world for good. I love both these women and also the very different little boys they have given me. That I almost didn't get to have the one who needs me the most seems outrageous: like a stolen twin baby only returned by accident.