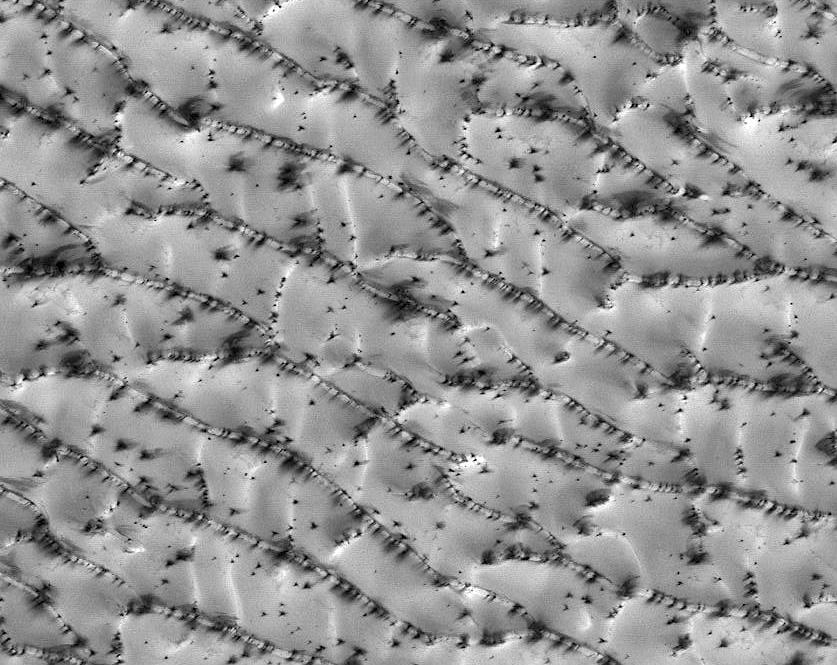

Photo courtesy of NASA's image library

Good Lady of Many Names—Onktkommer and Uncumber, She who prevents suffering, grieving Kümmernis and sorrowful Frasobliwa, She who liberates us—Liberata, Librada, and She who rids us of our pains, Dèbarras—I beg you: set me free.

Before your single golden slipper, the other given to the fiddler who gifted you song, I offer you oats. I have no money, no riches nor jewels to give you, all I have are these oats, which would sow the seeds for the harvest. My Lady, give me mercy as God gave you when you refused to be given away like meat to hands that would bring you harm.

Make me abhorrent.

Make me ugly.

Make me seen as I want to be known.

Release me.

Merciful Lady, rid us of our tribulations. We are dying.

Beloved of the Gods and Holy Spirits, Saint Wilgefortis, Crucified Princess and Martyr—pray for us.

(Patient 0: The Girl)

In spring, the beards grew.

The first one grew on the chin of a girl no more than 12 years old. She felt the bristles when she rubbed her chin against her shoulder to wipe March dew off of her face. They left thin white tracks against her flesh. She dragged her nails against the strands: dark, thick, and coarse. She took her father's razor to her face. The porcelain sink stained red from wounded skin. The hairs remained.

Her mother saw the dark shadow along her chin three days later and grabbed her daughter by the jaw.

"Do you think you are a man?"

The next morning, her mother took her to the doctor, and the girl began to bleed for the very first time. It was knives in the pit of her stomach, shattering her pelvis. Her jaw ached as she clenched her teeth through the squeeze of blood in her stomach while the doctor kneeled down to her line of sight and told her with a smile, "Razors are not for little girls to use. It'll just grow back thicker. You don't want that, right?"

For the x-ray, her doctor ordered her to drink water until she felt like she was about to burst. "Drink until your bladder is full, and don't eat anything before the ultrasound. Just pretend there is a baby inside of you," the doctor said. "Think of it as training for when you grow up. It'll be quite similar, I reckon."

The thought of a baby growing inside her made the girl scream.

On the morning of her appointment, she refused to drink. Her mother forced ten cups of water down her throat. When she tried to relieve herself before the appointment, her mother pulled her hair until the girl cried out.

"We are going to get rid of this as soon as possible. You'll thank me sooner or later."

Her stomach ballooned, full of water and urine and blood, straining against the confines of her skirt, and she cried as the cool gel was spread across her belly. As the nurse moved the probe across her skin, the bulging slope of her body disgusted her.

"Hold it in," the nurse said.

The girl cried, "I can't."

"Hold it in, anyway."

When the ultrasound was finished, she rushed into the bathroom and locked the door. It took an hour for the nurse to convince her to come out. As they exited the medical center, despite the muggy heat of early June, her mother made her wrap a scarf around the lower half of her face. In the car, the mother told the girl to keep the scarf on while the air conditioner blasted.

The girl took off her scarf when they arrived home and her mother wouldn't look at her.

When alone in her room, the girl turned on her desk lamp and drew a red marker on her stomach where her uterus would be, tracing the rough shape of the organ and making little marks where the scalpel would cut it out once she was old enough.

The doctors found no fluid-filled sacs, no tumors, nothing malignant nor benign, in her uterine walls. The hormones in their daughter's blood and DNA were average, the normal amount of estrogen, testosterone, and androgen a cisgender girl her age would have. There were no signs of excessive hair growth on other parts of her body besides her face.

The beard grew and grew, no matter how many times her mother took razors to the girl's fresh baby skin, still as soft as when she was a newborn. Hot wax, honey sweet and thick, only made the girl scream from the pain when her mother ripped it off. The dark hairs disintegrated under ultraviolet lasers, only to grow back in minutes. Hundreds of dollars were spent, all for nothing.

Her mother soon decided: "Nobody can see you."

And so they hid their bearded 12-year-old girl away in her bedroom, took no more visitors, and schooled her from home. The girl picked out oats from the porridge and banana bread her mother made, placing them on her windowsill as she looked out at the giant fir trees. She braided the strands of her beard together and waited for the day it would be long enough for her to scale the walls.

(Patient 157: The Maiden)

The Saint had been with her without name since she was a child.

Her patron Saint had been hidden behind the emaciated corpse hung on crosses, lit by stained-glass of rotating colors and fluorescent lights. Though the corpse, sculpted from plaster and wire, was flat-chested and bleeding from protruding ribs, her Saint shared its likeness so well that though the pastors and priests would call upon her as false over the centuries, as mere myth born out hysteria, the Maiden knew her Saint was real. Her Saint had breasts, dark robes hugging her curves, and a chin coated by bristles, hairs, and wiry strands, folded into the wrinkles of her dress.

Her Saint and the corpse of the Holy Son who decorated churches, cathedrals, and shrines all across the world were twins, but the woman with the beard was her savior, and her Saint had blessed the maiden from birth.

When she began to see echoes of her Saint out in the world, the Maiden felt no fear as many did. Women who had only known soft hairs on their cheeks now knew the harsh bristles that had lingered on the maiden's face since she was a child. They were forced to understand her in some part, now. The Maiden walked amongst the women with beards and was at peace. Though she was lapsed Catholic, excommunicated by her existence as a woman who did not fit the strict criteria of a binary sitting on a house of cards—she, a trans woman of neuroscience and lab studies, found solace in a modest church pew, knees pressed against the wood.

She did not pray, but she breathed. She removed one shoe and offered oats. In the echoes of the ceiling, she heard the plucked strings of a fiddle.

Her Saint came to her.

"Are you freed from your tribulations?" asked her Saint.

The Maiden smiled. "Yes. You've helped me. Thank you."

Her Saint kissed her shaven face, and the Maiden knew she and her fellow women would always have the choice bestowed to them. Other women like her did not mind the hair that had been growing on their chins and cheeks since adolescence. Other trans women would prefer to keep their beards, but not the Maiden. She found them a nuisance, but her Saint had healed her.

A fiddle's strings echoed in the bannisters of the cathedral, and her Saint's beautiful, bearded face glimmered gold.

Not a single hair grew on the maiden's face ever again.

(Patient 567: The Wife)

The woman had been a good girl. A good daughter, then a better wife. Her mother taught her how to sew the holes in pants and shirts by the time she was seven. She could make a full course dinner by the time she was ten, her fingers scented with rosemary, basil, olive oil, and the grease of pot roast. Her skin was clear of blemish and scarring, the result of a rigid routine, cleanser stinging against her open pores. She ate well, counting her calories under her Mother's watch. Her father wore a matching ring with her he had her promise not to take off until she was married to a man she loved. She was not to take it off until her wedding day, when the protection would pass on to her husband. She wore it every day until she was 22, when her husband proposed to her on their college graduation day.

He'd been the first man she'd dated, the first she'd ever been with. She didn't let him penetrate her throughout college, where they met at the Greek Living Gala at the beginning of their freshman year—fingers around his cock didn't count as sex, that's what her mother told her. So long as she didn't let anything inside of her—not fingers, not a cock, a tongue, if she did not wrap her lips around his cock—it would not count as sex.

Mother warned her it would hurt, "You'll bleed, and you will enjoy it." Mother had not warned her how much.

She'd known no other man—not a woman, had not allowed herself—so she rolled her hips through the pain that swelled with the pressure against her lower organs and wrapped her legs around his waist. She bit her inner cheek hard enough to taste iron as the pressure burst, matching the sheets below with red. Her pelvis bones pressed against her skin, and she held her husband to her breast like a babe as he came. On occasion, there was a sliver of pleasure. A rub against a soft bead, making her thighs twitch and stomach clench with heat, but it would be gone as soon as he was inside to the hilt.

The diploma holding her degree in religious studies sat on the fireplace mantle next to her husband's. Her husband's diploma remained open. Even in summer, she kept the fire going, and she'd watch the brisk light lick at the hems of the sleek blue diploma folder. She contemplated throwing her diploma into the electric fireplace. She didn't remember a single thing from any of her classes. She didn't remember why she'd studied at all.

They were going to have children: not yet, but in three years, when she was 25 and he 28, then they would have children. He made sure to pull out before he came inside of her, but he kept her legs spread and took in the streaks of salty white against her cunt and the inside of her thighs. Sometimes he'd trace a finger over the trails they'd made. Though he had no desire for children just yet, he enjoyed the act of sex and the ritual of it: the fondling of her backside, the stroke of her hair, and her deft fingers against his belt, practiced and coerced by muscle memory. The squeeze of tender flesh beneath his fingertips, the sink of nails into pink—not enough to pierce, but enough to mark.

The woman had no feelings towards it whatsoever. When he finished, she would simply offer him a smile.

After fucking her against the kitchen counter two months into their marriage, he pulled on a strand of hair rising up from her thigh, streaking towards the careful cut of her pubic hairs. She hitched a half-gasp when he pulled the hair out.

"Why don't you take a day at the spa this weekend? I'll book it for you." He smiled. "I'll make sure you get a wax and massage."

Her thighs and cervix were dotted with raised, reddened pores when she left the spa. They left dots of blood on the inside of her underwear and skirt. Her clothes chafed against the raw skin.

He bought her clothes for her. Her jewelry, shoes, the brand of makeup that looked best on her, the eyeshadow palettes that best brought out the shade of her eyes, and facial routine. Little by little, more of her things she'd had previously began to be replaced by new items bought for her. There was only one set of clothing her husband urged her to keep, one he'd ask her to wear some nights when he felt particularly adventurous.

"I'm glad your uniform still fits you," he said, sliding a hand underneath the plaid skirt she used to wear every day to high school. "You look so sexy like this."

The woman felt the hairs on her sideburns when she was doing her facial routine at the same time she did every morning: 7:30, the smell of coffee wafting through the vents, and the water cold on her fingers. Perspiration from spring rain on the windows. She thought the first strand was just a stray peach fuzz that grew too long. She pulled. It did not relent.

The hair grew from the sides of her face to the cut of her jaw in two days. Fields of bristles and strands grew out of the under-skin of her chin. She touched her cheek bones and felt the soft carpet of fuzz harden and bristle beneath her nails. When she managed to pull a strand out, it was thick and visible between the cuticles. The pore where she'd ripped it out bled, reddened, and faded. A fresh strand grew out not ten minutes later. The hairs she carefully plucked from her upper lip lengthened into a mustache of light brown, each individual bristle visible against her skin.

By the time her husband returned a week later from a business trip, the beard had grown long enough for the tip to slip between the line of her cleavage, nestling into the collar of her shirt. No matter the amount of times she attempted to shave it off, the hair grew back in hours, then minutes. She gave up after three days.

When her husband saw her, he did not recognize her. He thought she was an exhibit from a traveling freak show his grandparents used to speak of. It was when he heard her voice come from those hairy lips that he realized it was his wife. Her husband felt his own chin that couldn't grow more than scruff. He would not touch her.

The Wife had been so afraid the whole week, but when he saw her, she felt none of that fear. She was surprised at herself: the expression of horror and growing disgust didn't hurt her. His reluctance to touch her, lay in their bed or eat at their table with her, brought her no pain. He left on another business trip two weeks later and did not come back.

In the home now completely her own, she made herself a bowl of oatmeal, thickened with coconut milk, honey, raspberries, and pumpkin seeds. The dry oats she didn't eat were left on the kitchen windowsill.

(Patient 82: The Crone)

Wrinkles set in the flesh like folds of old sheets smelling of dust and the scent of bodies shifting through the decades. Her hair had long since lost its color, bright and dark shades fading into pepper, gray, and white. The hair fell to the floor, the shoulders, visible against dark, loose fabrics. It was best to let the flesh breathe instead of being confined in clothing that could jostle bones far more brittle than they once were.

Her husband had passed ten years ago, his mind gone before his body. Late April, the anniversary of his body's death. Her children scattered, her grandchildren drifted on wind, teetering back to her when they remembered her gifts of rings, earrings, and childhood toys carved by her own hands. The only things growing with the vigor of life were the pots of basil in her window, the sill only large enough for one pot and a succulent.

She felt the beard when she washed her face, her hands moving to the sink with routined muscle before the light, as she washed the sleep and sweat from her wrinkles. The light switched on, and her beard was white as the curls on her head, the strands thin on her scale and exposing liver spots and wizened flesh.

The beard was full, far more handsome than the goats of her own great-grandfather's family farm in the Alps, curling at the end with a single peppery streak. Her husband had once joked that such a beard would fit her austere face, and she'd known it wasn't an insult.

She washed her face, made her morning coffee, and watered her succulent and basil. She hungered for oats.

(Patient 42: The Boy)

The boy was 16 when he felt the first bristles on his chin. He'd been preparing for his Spring Recital. Legally known by his parents under a name he did not see as his own, but made for him when he was only hours born, he had never been able to grow facial hair in the way so many men could. The hairs were as dark as the coils on his head, black against his deep brown skin, and as he brushed his fingers against the tips, he smiled.

His vision was a crisp 20/20, but the words on the music sheets were blurs moving from line to line, the letters jumping from side to side, dancing just as the notes did. Looking at his music sheets for "Je te veux" for too long made the front lobe of his skull threaten to split open, but his fingers danced to the keys, color coded by dots and the stickers textured to his fingers, memorizing by ear and touch. When reading became too stressful, he sat at his bench and meditated, controlling his breathing and feeling his fingers against the keys, and then returned to playing. His father often worried about whether or not the boy could take the strain reading music required, but the boy was determined. He was too anxious to tell his father his father's child was not a daughter, but a son through written words, but his music would speak for him. Music was the language he best understood.

Now, the boy stroked his chin, dragged a fingertip along the coarse tips, and relaxed into his piano chair.

He started to brush the edges of his music notes, the sheets given to him by his teacher and the ones he wrote himself, the scraps of spoken word and rap beats and stanzas he'd jot down in a flourish at the height of an early morning inspirational high, against his chin. The bristles made the sound of velcro against the edges, and they vibrated into his shoulder blades, loosening the tense muscles through his biceps, all the way to his knuckles. The tension in his body melted.

On a blank music sheet, he wrote a hymn: a tango of piano, deep, droning beats, and a cello echoing the mournful wail of the human voice. He couldn't quite decide on the title, but imagined a defiant Saint, her smile coy and hidden amongst coils of hair, hated by a father who saw his child as little more than chattel. A child who spoke to God and was granted a wish for safety.

Music was his God, and God spoke to him through his fingers, and his lyrics and notes were his worship. He wrote his symphony, and his signature was "Luca." His true name, not the name he would let wither and die on his birth certificate. He would not be known as his parent's daughter, but their son.

Before an audience of faces obscured by the shadow of bright lights striking hot against his skin, an audience largely decorated by similar bristles and strands as was on his face—men, women, little girls, others—he took his bow and plucked the stringed ribs of his cello, and the boy—the son of his father and mother—spoke to God and the Saint.

(Patient 5542349: The Bearded Lady)

In the dim light of the pub, the bearded ladies broke bread, shared a table, and made a toast with their chilled glasses. Over their beer, they invoked the names of their late sisters.

"To Julia Pastrana."

"To Krao Farini."

"To Anne Jones."

"To Jennifer Miller."

"To Helena Antonia."

"And to all the bearded ladies—May your beards not be scraggly but as fine and luscious as ours!"

As they drank, they laughed into their beer, the foam sticking to the thick curls and strands lining their beatific lips, the curves of their chins and cheeks, trailing down their necks to their breasts.