Photo courtesy of NASA's image library

I rode the track to its terminus at the village of Haran, and emptiness unrolled before me to the far meeting of earth and sky.

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

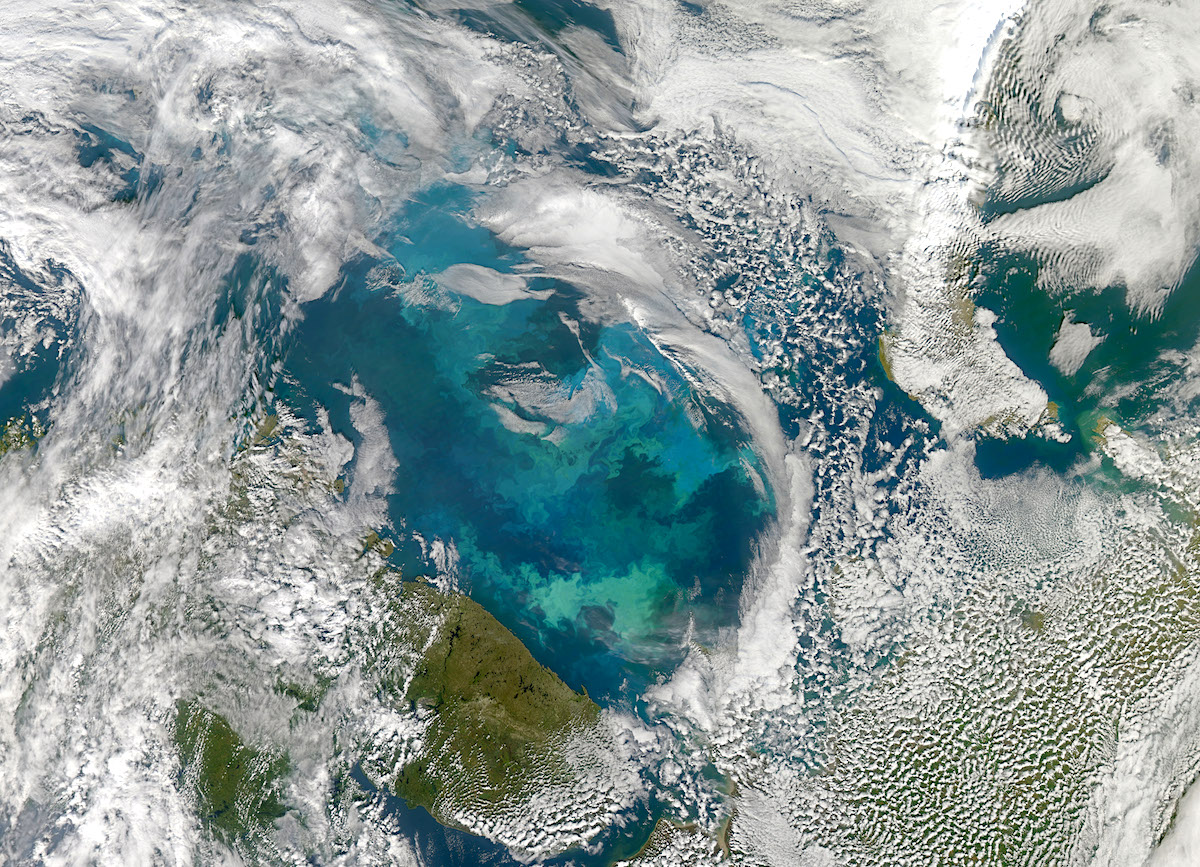

There were two islands visible from the shore, and the larger of these was Chatakdal. Chatakdal was formed in the shape of a camel-ish double hump, its windswept grasses a pale, parched green, which gave the island its saurian aspect: a dreamlike abstraction of a lizard sunning in the shallows of the Andelman Sea. The other island, Gumeshel, was in the shape of a mesa and lay several kilometers farther out. Roughly the size of a football pitch, it existed chiefly as a blemish on the horizon, visible only in the mornings, before it was swallowed by the midday haze rising from the sea.

I was staying in a pension in the town of Turgusten, a former fishing village whose (overly aspirational) transformation into an international tourist destination had been arrested by a renewal of separatist activity in the east. A spate of terrorist attacks, including a bloody bombing in the capital, had frightened off foreign visitors, and this late in the spring, when the tourist season should have been ramping up, the country's southern beaches lay all but empty.

The building boom, funded by speculators from the country's moneyed northwestern provinces, had given the town an abundance of boxy, white resorts with fanciful if appallingly kitsch names ("The Princess Breeze," "The Ocean Palace"), but after a trilogy of low seasons, these had already begun to fall into disrepair, the decadence manifesting with metaphorical emphasis in the empty swimming pools and cracked whitewash surfaces I passed by each day, wandering the beach on my excursions northward and southward along the coast.

With the end of the academic term at the international school and the completion of my teaching duties, I'd come down from the still-rainy capital in search of sun and rejuvenation, and the sea waters, though far from warm, had lost enough of their wintry bite to swim in. I had little else to occupy my time and few people to talk to (an arrangement I'd chosen by design, and which I was coming to regret), and the greater part of my day was given to swimming dilatory laps a few meters from the shore or reading from the crate of novels I'd lugged here with me. The town seemed to be devoid of anyone between the ages of 18 and 35, and the population skewed much older, so a geriatric torpor prevailed, something my morning swims could do little to combat.

My chief source of social interaction in town was the manager of my pension. Lacking other guests, Hazam, a dark, thick-necked ex-sailor who'd learned Amarguese in the Garamdi merchant-marine, had pressed me into service as his evening dinner companion. I'd been reluctant, at first, to foster too close an intimacy with the hotelier, who seemed to wear an expression of perpetual suspicion, but the dinner was included in the board, and the dishes, prepared by our laconic Daari chef, Musuf, were too good to pass up.

We talked, Hazam and I, chiefly of girls: where we might find them, strategies for seducing them, how they might be enticed back to the hotel, and the relative merits of women of different cities, different provinces, different nations; i.e., where could be found the prettiest and—a more pressing concern for the two of us—where the easiest.

Although Hazam spoke in a way tending towards the reminiscent (he was in his late 30s), especially about the (brief) heyday of Turgusten as a tourist destination ("The parties here in the summer, you can't imagine!") I found he was, uncharacteristically for the lothario he seemed plainly to be—or, at the very least, to have been—restrained with respect to the details of his individual conquests, and this I respected about him. He did not share his conquests to boast, merely because it was the only way to get the point across, and he spoke of the psychology of woman with the detached attitude of a jaded businessman or a long-disillusioned academic, whose aspirations had diminished to the simple exchange of practical knowledge, man to man.

I also found he was fond of the Amarguese word "fuck":

"I would never pay a girl to fuck, and I have never needed to."

"Those fuckers in the capital could have saved us a lot of money if they'd just ended the war in the east."

"But did you fuck her?"

This last question, he asked of any story I told featuring a woman, however tangentially, and I noticed his eyes would glaze over with boredom if the story went too long, as if the soul had freed itself of the burden of the corpus, and not till I had announced the story's end would the light of reason return to his eyes, and he would ask this question, which seemed, for him, the sole determinant of any anecdote's worth.

Although otherwise crude, Hazam arranged our dinners with as much fastidiousness as if they were held in the officers' quarters. Each evening, Musuf laid out an unblemished, bleach-white tablecloth surmounted with impeccably laid utensils and plates, and Hazam and I would sit at exactly six and twelve. Arranged this way, our prandial conversations had something of the form, if not the content, of salonic philosophical debates. Hazam's costume at these dinners was a tight, starch-white dinner-shirt, which ill suited him as drastically as it would have a gorilla.

The conversations were not unedifying, certainly not unentertaining, but I tended to reach my limit at about the 70 minute mark, and I would pack off shortly thereafter to escape to a teahouse in the town's center, where I could do some reading (my chief companion, Alastair Penningten's volumes-long account of his travels through Garamdal 30 years ago), leaving Musuf to occupy Hazam's time with endless, smoke-ringed games of grimly-contested backgammon.

A week of such debates passed before I saw for the first time a girl who seemed pursuable. Arriving at the teahouse after dinner one evening, I discovered, sitting in a wood-trimmed alcove (the teahouse was centuries old, its beams imported cedar, its brick walls dating to the golden age of the old Garamdi empire), a young university student, perhaps 20, reading from an oversized book while a metal carafe steamed at her side. She had a serious air, or it was a combination of her dress (a slim, black turtleneck), her makeup (generous eyeliner), or her facial expression (unhappy to be studying at this hour), that gave me this impression, but the seriousness seemed unsuited to her age.

Seeing her, I took a moment to judge my chances, felt discouraged, and then decided to talk to her anyway.

I walked up and asked her, in Garamdi, What are you reading there?

She lifted her eyes and looked at me appraisingly before tilting up the thin cover of her textbook. It was a cheap student's edition, common in the country.

You're a student.

I am.

You're studying for your exam?

I am.

How's the studying going?

She shrugged her shoulders, paused a beat as if expecting me to ask another question, and then said the Garamdi phrase meaning, "Okay." Her tone seemed to be one of declarative boredom, untinctured even by an explanatory admixture of suspicion.

I'd found in my travels in the country that speaking Garamdi as a foreigner was sufficient entrée to most conversations, and I felt discomposed to have run across someone so unimpressed with my status as a foreigner.

I wonder— I began tentatively, and then she brought her eyes back down to her book, leaving me stranded, standing, it seemed, for no reason in particular before her small wooden table in this little alcove.

Have a good evening, I said to her.

She hummed a reply.

Humbled, I staggered to a table on the room's far side and debated leaving town, leaving the country. But I tried to distract myself with the Penningten. I avoided looking at her alcove for some time, and when I did, I found she'd packed her things and gone.

I own to an abiding fondness for the Garamdi. Beneath their reserve I know them to be a gracious, generous, hospitable and sensitive people. Perhaps too sensitive at times, but if they are, they have good reason to be so. They are the creatures of their precarious geographic location.

Since antiquity, their land has been buffeted by the winds of conquest and empire. From the sea, the Vilinians. By land, the Rusch and the Qushi from the northeast, the Kalam and the Daari from the south. A plethora of peoples have walked their lands, and left their impress: The once-nomadic Daari still till the soil and drift with their sheep in the nation's far east. The fair-haired Galeni, long assimilated, live on in the sight of an occasional freckle.

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

In the mornings, I frequented a cafe near the marina. It was one of those places so old-fashioned, so marked by the prevailing style of the time they were built in, as to seem timeless: walls painted a sickly, faded lime, reflecting a mania for industrial pigments that had prevailed after the revolution, with furnishings seeming not to have changed in decades, dull chrome tables and peeling vinyl chairs spilling out from a pair of perpetually open double-doors onto the concrete landing preceding the marina. The place had a lively atmosphere because many of the artisanal fishermen stopped here after spending the early hours of the morning working the waters off the coast. Here, old men in fishing caps spent the forenoon holding forth in animated debates I was at a loss to decipher, the gravelly rumbling of which formed a kind of pleasant hubbub above my attempts to read the newspaper. These men largely ignored me, a foreigner was no novelty in a town that had once aspired to tourism, so I drank my coffee in peace and could concentrate on puzzling out, with the aid of a Garamdi dictionary, the day's news.

In the capital, I listened to Amarguese radio and picked up the international editions of Amarguese newspapers, and these served to remind me a world outside of Garamdal existed, but in this town, my world was so diminished, I resembled those subterranean creatures with withered, vestigialized sensory apparati capable of gathering only the information at claw-reach. Two papers, Bahshal (Citizen), a conservative paper which served as an organ of the Nationalist Party, and Republik (Republic), the leading paper of the opposition, served as my morning reading. What I liked about them was the charming foreign quaintness of the writing styles. The editorials addressed the reader directly, with servantish obsequiousness and a courtly prolixity, something of the air of a vizier addressing his king (Esteemed reader, it has recently come to the attention of this humble columnist that some in our modern and educated country still feel it is acceptable to denigrate our countrywomen in public. Why just the other day, stepping off the tram, I was witness to an episode that outrages...). This was married to the clipped, telegrammic prose of its news bulletins (Inflation measured at 10.9% over the past year; Ministry of defense orders more tanks; Heroin ring dismantled in [the city of] Ijif), and these two styles formed a sort of master tutorial in Garamdi reading comprehension.

The morning after my abortive conversation with the girl at the teahouse, I puzzled over an editorial about the role of various eastern dialects in the education system. Among the bulletins, some business about the latest Vilinian provocations at sea, but not until later that day would I understand the news I had skimmed. Walking back to the pension from the marina, I saw a speedboat racing up and down the shore, its noise all out of proportion with its size. When I reached the pension, I saw Hazam standing out front, watching the shore, his posture clenched. I came up to him, and his eyes didn't shift from the horizon.

"They want to take our islands!" he practically shouted as I came up to him.

"Who?"

"The Vilinians! Who else?"

"What're they doing?"

He turned to me. "They are trying to take Gumeshel. Look, you see on the island?"

I looked at the island, a squat grey blob thinner than my pinky. "What am I supposed to—"

"They put their fucking flag on our island!"

Hazam's sailor's eyes were arguably better than mine, but a flag flying above the island would have been invisible to anyone who wasn't part hawk.

I hated asking him straight questions, because he tended to dodge these with the capriciousness of a caged predator, but with effort, I teased out the situation from him:

There were dozens of islets in the waters between the Garamdi mainland and the Vilinian home islands, and the status of these tiny islands had always been a point of contention between the two nations. In recent weeks, the new Garamdi government had begun making bellicose formal pronouncements about the islands, declaring all new maps published in the country would have to clearly indicate these islets formed a part of Garamdi territory. This seemed largely a ploy on the part of the Nationalist Party to invigorate the electorate during the shaky first days of the accession of their newest prime minister, an opaque provincial governor who'd been selected as a compromise candidate among the party's internal factions.

The Vilinian foreign ministry, for their part, did not take these provocative statements in stride, responding with a revised map of the eastern Andelman Sea, in which the islands were colored a royal Vilinian yellow. The two sides had been jaw-jawing for weeks by the time I'd arrived at the town, and now, in a spectacularly audacious move, the Vilinian navy had made a night-landing on Gumeshel and erected a flag pole on the island, upon which they'd hoisted the Vilinian flag. A press release was sent out. The stance of the Vilinian government had always been that Ikariona (the Vilinian name of the island) was a Vilinian island and had always been such. It was only natural the Vilinian flag should fly on Vilinian territory.

"The problem with this country is those fuckers have the balls, and we don't," Hazam grumbled.

I asked him what he thought the government would do in response to the provocation.

He shook his head. "Who knows?"

In the half century since the fall of the imperial dynasty and the rise of republican Garamdal, the country has undergone profound changes. Skyscrapers now overshadow the palaces of the former imperial capital, asphalt highways connect the villages of the provincial hinterland. The torch of the revolution, still a fresh memory, is carried on by the Nationalist Party, which has won every election in the country's history, and whose members dominate the Garamdi parliament.

I find myself one morning sitting in a cramped office in the city of Ijif for an interview with a mayoral candidate put up by the Nationalists. Flush with cash from the party, he has bombarded the airwaves with his presence, and trucks touting his ties to the party blare their messages at the oddest hours along the city's dusty avenues.

"What does the party mean to you?" I ask the would-be mayor through my interpreter.

"Ah, good sir. Why it is everything. Without the party, we are no nation."

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

That evening, intending to stretch my legs before dinner with Hazam, I wandered down the beach to the town of Berenis. The town was smaller than Turgusten and was just large enough to support a beach bar adjoining the ruins of an old seafort from the days of the empire. The walk was not long, perhaps 40 minutes, along a fresh concrete path installed by the municipality only a couple of years before, and by the time I reached town, the sun had already set, the sky's western edge still a vibrant, dying gold.

The bar hosted a handful of older couples, grey-haired, white-haired, only their affections seemed unturned by age, gripping each other's hands with the closeness of young lovers. I saw a girl in a light cardigan drinking alone as she smoked a cigarette and watched the colors of the sky change over the waters. Coming closer, I saw it was the girl from the teahouse.

We recognized each other at the same time, and a moment of mutual surprise passed before she lifted her hand to wave at me. Seeing by the smile on her face she was a little drunk, I felt emboldened and stepped through the cool sand to her table.

Good evening, I saluted as I approached, exchanging my stranger's salutation for the Garamdi familiar one.

Good evening to you, she responded invitingly, the smile still on her lips as she said this. I supposed it was the alcohol.

May I?

She shrugged noncommittally, Why not? and I sat down.

I never got your name, I told her.

Nesla, she answered, offering me a cigarette, which I waved off.

Nesla— I wanted to tell her I thought it was a pretty name, and then thought better of it: How's the exam studying going? She shrugged her shoulders and said a phrase in Garamdi meaning either, "What exam?" or, "What about the exam?" I couldn't tell which, and I decided to drop the subject.

I—I began, and then she interrupted me: Where are you from? she asked almost demandingly. I hadn't understood the peremptoriness of her question was characteristic of her (and thus something worth combatting), so I answered her question without hesitation.

When I told her, she looked surprised. I thought you were Amarguese.

I shrugged my shoulders and smiled. I'm sorry to disappoint.

How old are you?

Thirty.

She looked at me appraisingly. She had large eyes, the confidence to use them how she saw fit, and a slightly witchy nose that would have marred her face had she been older. On her, I found it fetching. You look younger.

People tell me that. How old are you?

Twenty-four, she said as she picked up a beer bottle and looked at something on the horizon.

That's old for a student, isn't it?

She laughed, surprised by my bluntness. I'm a bad student.

I looked her over. You look like a bad student.

She chuckled, her lips pressed into an "O," the Garamdi word for "yes." Oh, yes, she said, nodding. I am a bad student.

A waiter appeared, another youth with a haphazardly grown beard. I asked for two more beers, and when they came up, she insisted on paying for them.

What are you doing here? She tilted her head the way the Garamdi sometimes do when they ask a question. She meant in this town.

I'm just a tourist.

But why here? There's nothing here! She swept an arm back, emphasizing how expansively the nothing-here-ness extended.

Maybe I see it from a different perspective than you do. Nobody likes the town they grew up in.

She shook her head. I'm not from here.

I asked her where she was from, and she told me she was from the capital, explained she'd been sent down by her parents to study at her aunt's house. This wasn't completely out of the norm. The exit exams were a few weeks away, and few students spent the reading period at the university.

Attempting to find a point of commonality, I told her I also lived in the capital.

You're not a tourist, then. You seem, she pressed her gaze into mine, like a traveller. In Garamdi, she used the literary word, the one that means "wanderer." How long have you been here in Garamdal?

Two years.

What do you think of this country?

I paused before I answered. I love it here.

I hate this shitty country, she announced, less to me than to the spectacular dusk. I wish I could go somewhere else.

Where?

Anywhere! Somewhere far. She thrust her right wrist into the sky. As far as possible.

I told her I wanted to go to the east.

You aren't afraid? There are terrorists there. You could get killed in a bombing.

I didn't recognize the Garamdi word for "bombing" and asked her what it meant. She lifted her arms and threw her hands apart: "Pow!"

"Bombs!"

Yes.

I shrugged my shoulders.

You're brave, she assessed with an ironic smile, or reckless.

We drank until it got dark, and I offered to walk her back to Turgusten. As we walked the concrete path out of Berenis, I offered my elbow. She looked at it and shook her head, laughing.

No, she said as she ran off towards the town. But you’ll visit me tomorrow? Before I answered, she'd disappeared into the darkness.

Beyond the cliffs, a scrap of blue scape, the sea. These are the islands of antiquity. The land is arid, rocky, the sun, blinding, punishingly white. It is a barren land, but it has been said such lands as these are the most fertile soil for poets. The great epicists of antiquity hailed from these parts. Why, perhaps not far from this congeries of misshapen stones, which the archaeologists tell us were the remnants of the ancient city of Mirindar, Imiro Xano recited his masterworks to an assemblage of scribes hunched over papyrus scrolls. How bracing the realization one walks among the ghosts of such legendary figures. One's pen-hand is humbled, shall any of our own writings survive the merciless weathering of the millennia to come?

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

At the cafe the next morning, the day's papers were alight with reaction to the Vilinians' claiming of the island. The opinion writers at Republik portrayed the episode as typical Nationalist bungling, while Bahshal urged unity in the face of foreign threat. A spirit of levity and animation seemed to have overtaken the cafe. Old men in fishing caps argued excitedly about what the Vilinians had done. The debates were loud, but there seemed to be no edge of anger to them. Furthermore, the conversations at the tables around me were punctuated with bouts of laughter. The Vilinians were at the very least, an honorable enemy—these were not Daari terrorists—and they were better respected in these parts than the current suite of Garamdi politicians. A military flare-up, well, such matters were good for the national spirit.

From a pair of tables over, I watched a paunchy middle-aged man speak with one of the older fishermen. The fishermen here were men of the sea, their faces weathered by sun and wind, and as they aged, their features grew gnomic, wizened. This fisherman, who looked to be one of the oldest, had been reduced to a shrunken goblin, but he had a haleness that was the gift of the sea. The old man had launched an animated monologue, spoken in the tone of harangue, peppered with gesticulation, sometimes lasting several minutes. I searched, almost reflexively, for someone to point this out to, realizing as I turned to do this, I was thinking of Nesla.

In the country's east, a growing independence movement among the Daari tribes tests the mettle of republican conscripts. If the Nationalists can administer the remnants of the empire in a more capable fashion than the deposed emperor, they may gain the legitimacy they shed so much blood to win in the revolution. If they fail, the nation will be reduced to a rump state, prey to its more powerful neighbors.

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

After dinner, I called on Nesla at her aunt's apartment, a squat, white block of stucco near the town's central square. Little decoration adorned the apartment building, save a single television antenna, which jutted in an elbow from the building's northeastern corner. When I rang the doorbell, it was Nesla who answered and smiling with unexpected delight, leading me by the arm to the living room.

The aunt, Marjina, greeted me excitedly, glad for the opportunity to be hospitable to a foreigner. She was younger than I'd imagined, in her late 30s, slightly overweight in a way that thickened her arms and her thighs. Her hair, streaked with grey, she kept cropped short.

We sat in their small, tightly-packed living room, on an L of floral cotton-upholstered couches. Nesla and I shared the floral couch while the aunt, Marjina, sat on the corner sofa chair.

I was offered tea, which I sipped politely, and then we descended into an excited hush, broken only the sound of advertisements coming from the television. I wondered if I was meant to be the one to guide the evening's conversation.

Marjina broke the silence: So what do you do for a living? Nesla said you've traveled a great deal. Are you a journalist?

I shook my head. I'm a teacher.

Ah, she said, "Intellectual." She used the Amarguese word, which she enunciated in her heavy accent, and turned to her niece, laughing, a private joke.

I puzzled a little over why she considered teaching to be such an intellectual profession, but she began to assault me with a barrage of questions, and I dropped my puzzlement, trying to keep up with her and also return Nesla's expectant looks my way, whenever Marjina asked me a question.

Why had I come to Garamdal? What did I think of Garadmi people? How did I like life in the capital? Was it preferable to the south? Had I ever been married? Had children? These questions scarcely slowed until a serial came on the television which diverted their attention. So-called "girls' stories" were popular in the country. Alongside crime dramas, these constituted the majority of the nation's televised emissions. The stories were all the same: A young girl from the provinces comes to the big city where she must contend with the challenges of city life, or else a young girl from the big city comes to a small town in the provinces where she must contend with the challenged of provincial life, etc., etc. Eponymously named: Hana, Ijila, or toponymously, Aliyef Tale (I've visited Aliyef, the television serial covered all of the city's wrinkles), they all had the same arc, a girl goes from being an awkward fish out of water in a new place to finding love, to arriving at social triumph.

I observed Marjina and Nesla as they smoked and watched the serial, occasionally exchanging light, hurried words. The conversation with me had stalled now that a more interesting source of entertainment existed. I wondered how long I would have to watch TV with these two. Also, whether this modern-looking aunt was Nesla's chaperone or enabler. Unsure how to proceed, I elected for passivity, and my eyes wandered Marjina's home. On the wall above the television hung a portrait of Hazur Mufendis, the revolutionary, advertising plainly the aunt's politics.

The show ended. Hana, the doe-eyed protagonist was shocked to run into Aktan, her boyfriend of last season, as she wandered the shuttered of grounds of her childhood school. The season was climaxing, racing to its inevitable cliff-hanger conclusion. The credits rolled. Commercials for laundry detergents and skin creams followed.

Marjina stood up and arched her back in an unself-conscious reverse back-stretch, then strode to the kitchen where the hiss of a faucet and the clinking of pots seemed to indicate she was preparing another kettle of tea.

I turned to Nesla, who gave me an expectant look. I was about to say something when, on the television, the news came on, and a jolt ran through me as I saw Gumeshel and a graphic of the Garamdi west coast beside the newscaster. The talking heads introduced a segment about the military crisis.

Footage of Turgusten and of Chatakdal, and then Gumeshel. A map of the coast around Turgusten highlighted the tiny the islands, and a bright red arrow pointed to Gumeshel. A man in military uniform spoke with severity into a bouquet of microphones.

Marjina returned with tea, and Nesla and I shifted quickly apart. I asked the Marjina what she thought of the situation surrounding Gumeshel.

It's the Nationalists' fault for spouting their bullshit. Now they put us into a pissing contest with the Vilinians.

You don't think it was the Vilinian's fault for taking the island? I asked.

No. These Nationalists bit off more than they could chew.

But you're a Nationalist, aren't you? I glanced at the portrait of Mufendis, the founder of the Nationalist Party. Wasn't Hazur Mufendis a Nationalist? Marjina, gave me a look of surprise and then turned to Nesla, slyly with a look saying, "This one."

Yes... That is true. But Hazur Mufendis was a real man. If he did a thing, it was not be puffed up. Not to bark and not bite. He was strong. All these men who came after him were shit. She smiled, Actually, I correct myself: All men are shit!

Auntie!, Nesla protested.

I don't include you in this, Marjina said to me with a pleased, ironic smile. Here, drink.

In the town of Haran, I greet a classroom of eleven-year-olds. Hanging on the wall above the blackboard, a portrait of Hazur Mufendis overlooks with what seems to be pride, the future of the nation. Of the revolutionaries who can be considered the republic's founding fathers, Mufendis can be said to be foremost, and it is to his legend the Nationalist's have yoked their claim to legitimacy.

His is the story of the great men of history. An imperial childhood. Learning to read by firelight in a provincial village far in the empire's hinterland. A father imprisoned by the imperial secret police. A career as a lawyer and then a revolutionary firebrand. It must certainly be flattering, even posthumously, to have one's image littered about one's country with such proselytic, but I wonder what he would think of the country, or of his party, today.

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

Some years ago, before I set off on my travels, I'd found, in an old travel magazine, a series of photographs of the Garamdi far east. I suppose these would have been taken around the same time Penningten had made his travels in the country. A horse-drawn carriage, braving an icy village lane in the wintertime, its wheels replaced with sled-skis, the flanks and legs of the horses frosted with snow; a trio of rifle-toting soldiers wandering a poppy field, the first blooms white against the summery greenness; an old woman hefting an enormous wooden spatula before a clay bread-oven, its embers glowing with demonic intensity; and, most startlingly for me, a young Dari girl, perhaps 12, in an anonymous village house, cradling a newborn goat in her arms, laughing into the camera. She had dark eyes, exquisite lashes, densely-knitted eyebrows; this thin child, with a face framed by pigtails, seemed a creature out of time, citizen, or subject, of a nation, an empire, that either no longer existed, or had never existed at all. When Marjina asked me, Why did you come to Gardamal? although I could have given her any number of ready answers that would have satisfied her, none of them could have done justice to the truth, and the only honest answer to give her would have been to point to the photograph (which I have never been able to find again) of that laughing little girl.

Nesla and I settled into a sort of simulacrum of courtship. We met in the evenings at the teahouse and stayed until closing, earlier now after the imposition of a curfew that emptied the streets of the town past dark, and making our way back to her aunt's house, I could kiss her in the shadowed sections of the dark streets, a frisson of danger adding to the pleasure of these episodes. She turned down any suggestion we should meet, alone, somewhere in private, but in truth this kissing in the dark was already more than I'd expected of my sojourn here.

I imagined for her a life in the capital she seemed reluctant to discuss. I'd asked her what part of the city she lived in, and she'd named a district I recognized, though it was far from the quarter where I rented my own flat, as one belonging to the slim, perpetually precarious Garamdi middle class. Her father would have been a tradesman, then, or a government bureaucrat, her mother a housewife or a clerk. Inflation, the threat of unemployment, the unseemly press of rural peasants who came into the city every year and made of the capital's outer districts a zone of poverty, these all were a sort of vague threat to that wary, anxious class.

I discovered she read a great deal, and we spent a fair amount of time discussing various Garamdi and Amarguese authors (the Amarguese ones she'd read in translation, her knowledge of Amarguese, in spite of a course in the language at school, no better than her aunt's). Though I was initially surprised by this, I decided I could square her well-readness with her bad-student-ness by recognizing her love of reading derived more from a penchant for idleness than a driving intellectual curiosity.

How long will you be here? she asked me one evening.

I couldn't tell whether this question reflected a shift in her feelings towards me. I had planned only a few more weeks here in the south, before I returned to the capital. I would have stayed for her, but I didn't know how to say this to her, or if it would help if I did.

I read the progress of the crisis in the papers each morning. Although it concerned me, in a way, although it was passing all around me, the thing had an air of irreality. That I was on the ground so to speak made the crisis no less virtual. In the dueling editorial pages of Bahshal and Republik, the Nationalists and their opposition rattled their respective rhetorical sabres. Bahshal's editorialists condemned "those who would seek to weaken the resolve of our armed forces in the midst of a conflict," while the opposition, sensing weakness, pounced on the new prime minister "not up to the task," "an incompetent provincial," and this partisan squabbling made the thing feel distant, an affair in the capital.

When fishing vessels were banned from operating in the waters off the coast, the cafe became a gathering place for the now disemployed fishermen, whose initial amusement at the situation had spoiled into upset, now that it was beginning to affect their livelihoods. The morning grumbling had begun to take on the air of revolutionary grievance.

There had been an abortive attempt to reclaim the island. It came out in the papers, the Vilinians had fired warning shots at the approach of a Garamdi corvette drawn too close to the island, and this, the warning shots, had been threat enough, apparently, for the navy to stand down. ("I told you, no balls," Hazam declared when I asked him about the episode.)

Do you have a girlfriend?

This question Nesla asked me later at the teahouse. The answer was no, and when I asked her if she had a boyfriend, I was surprised when she said yes. A classmate at the university, whom she'd been seeing for a year.

I asked her if this was why she had blown me off the night I had first tried to talk to her at the teahouse.

No! He doesn't own me. I can talk to a man if I want to.

Then why?

Because! You seemed like some kind of playboy. Some foreigner who travels here and there. You talk to some girl. You try to sleep with her... Is that what you do? That she smiled as she said this, as if she had some wry rhetorical point, left me feeling backfooted. I felt each of us knew a thing the other did not know, and because of this we were locked in a sort of awkward asymmetrical combat, in which she seemed perpetually reaching for an upper hand.

This was, of course, partly a relationship of convenience, but I felt I could lose grasp of the thing at any moment, and there was warmth in that, the sense of precariousness. It was the sense I could spoil things if I made a mistake that helped lend the thing its feeling, and this sense hastened my steps each evening to meet with her at the teahouse.

Could the country modernize? The electrification of the far east, universal schooling, the expropriation of private lands and their redistribution to the peasant farmers, the fruits of republicanism. These are the nation's hope.

—Alastair Penningten, Voyages in Garamdal

A warship was moored off the coast.

"It's a destroyer," Hazam announced to me as we watched it in the morning light. "We've got about a dozen of them in the navy."

At the crest of the taller of the hills of Chatakdal, the Garamdi national flag flapped defiantly in the morning breeze.

"They'll see how close they can get. These are all our waters. I mean to say, it's either theirs or ours. There's no international waters here, you understand? We're either in their waters or they're in our waters. The only way to see whether it's our waters or their waters is to go there. If they fire on us, it means it's their waters. If we fire on them, that's how we show them it's ours."

There was a weariness in his voice surprising to me. War was no good for business, and the Vilinian tourists who might have cushioned the loss of other foreign visitors, he could be sure to write off, along with whatever rich Garamdi northerners would have thought to make a summer holiday in the beaches here, if not for the presence of battleships to mar their tranquil ocean views.

Hazam told me if the pension went under, he might go home, a village in the east, far in the country's interior. He recounted to me a little of his hardscrabble childhood. "I never saw the sea until I was eighteen! Pictures, sure. On TV, but never in person."

Looking out at the sea, he seemed to want to take it in, save it, as if he already anticipated losing it.

"There's nothing like it, being at sea. Yeah the work was shit, but you never had the land bullshit to deal with. You had the ship bullshit, but it's not so much, compared to the land bullshit. There was real peace, at sea."

He suggested we make a trip together to a bordel in the provincial capital, another coastal city further south, a three-hour car ride away. I had no opposition in principle to paying a woman for sex, but for me it put in mind too much the question of hygiene to go with another man, or with this man in particular.

And there was another thing: "You said you'd never paid a woman for sex."

He shrugged. "You do not pay the woman. You pay the madame."

The crisis passed with surprising anti-climacticism. Thanks to the 11th-hour intercession of the Amarguese foreign minister, who it was said, spent 24 sleepless hours working the phones, the two governments agreed to stand down their navies, and the flag on Gumeshel was removed by Amarguese marines. The status of the islands was left unspecified and an arbitration committee was to be formed under Amarguese auspices to determine the fate of the islands.

The resolution of the crisis had opened a space for me to be reflective. My life was my own again, and not dominated by the day's news. I returned to my troglodyte existence, that subterranean creature who knew nothing of the outside world. The newspapers I was accustomed to picking up every morning at the kiosk by the marina, I left un-purchased, returning instead to the novels I'd brought with me. During the crisis, I'd scarcely felt able to concentrate, and now I was forced to consider the question I'd come here to resolve: what path would I take from here? A new teaching contract. Returning west. Going further, traveling further. I felt a free man, and rather than being weighted down by the consequentiality of the choice I would have to make, I felt very light, as if traveling with no luggage.

Nesla and I discussed making a trip together. The summer stretched before me, inviting, open, a track through open land toward a boundless horizon.

With the next girl you meet, you should be more aggressive, she told me in bed one morning. You could have slept with me much earlier if you'd told me what to do.

I raised my eyebrows.

I'm giving you advice. I'm telling you about the next girl you meet.

I told her I wanted to take her traveling with me, but she demurred, using the thin excuse of her exams. I argued with her about it until she finally admitted her boyfriend would be arriving in a few days.

At the bus station in the morning, I drank tepid coffee out of a paper cup and sat in a waiting room occupied by old men and women clutching cheap suitcases and bags of woven plastic overflowing with bundles of clothing. Nesla had volunteered to come with me, and when I picked her up from her aunt's house, I was surprised to find another Nesla I had failed to know. She was pale, her hair unbrushed, wearing a t-shirt and loose pants. Without her makeup, I saw she was faintly freckled, and I thought of Penningten: The fair-haired Galeni live on in the sight of an occasional freckle.

In the waiting room, she'd curled up against me, still sleepy. I offered her the coffee, which she waved away.

Call me when you get back to the capital, and let me know you made it home safe.

I told her I would, and she asked me if I would want to see her when she returned to the capital in the fall.

What about your boyfriend?

You can still talk to me. It's not a crime to talk to a man.

I felt uncomfortably aware of the audibility of our conversation in this quiet room.

I'm not sure that's something he'd be comfortable with.

She cradled her head in my chest, yawned, exaggeratedly, it seemed. She clasped her hands in mine.

It struck me our relationship had followed the arc of a television show: A girl from the capital comes to a beach town in the south to study for her exams... She'd lived that show. So, for that matter, had I.

Stay, she said quietly.

I smiled reflexively, and I was pleased at the thought she wouldn't see this smile. I cradled her in my arms. She was light and as warm as a wounded bird. We were both quiet a long time, and I supposed she was wondering what I was thinking. Perhaps not, and if she had asked, I would not have told her the truth or been capable of telling her the truth. An image prevailed in my mind: a village girl laughing as she held a newborn goat. I was thinking of all the plans I had ever made.

I lowered my chin to the side of her forehead.

I opened my mouth to speak.