|

|

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Nonfiction |

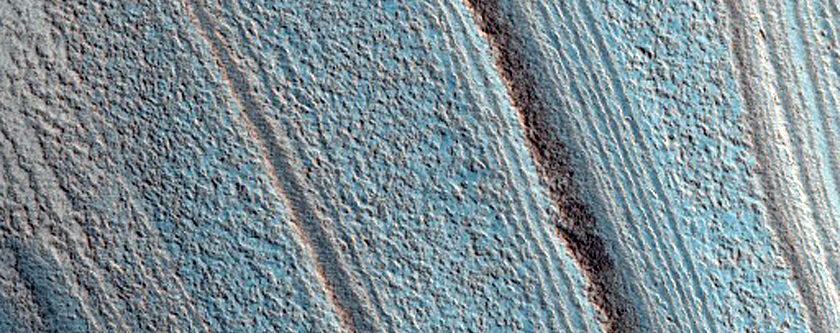

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

Through a speaker, the principal tells the author of this story and his classmates:

"A tornado has touched down less than a mile southwest of the school."

The author of this story and his classmates are eight, are nine, are at work on their timelines.

They will hang in the hall.

Long-told of their homes', their two-stories', their trailers', their farms', their livehoods' perilous parking in tornado alley, the author of this story and his classmates have particular and concrete fears of the weather.

There is not a tornado outside.

The principal, through a speaker: "I repeat: One is on the ground and moving thisaway."

There is not a tornado outside, and the author of this story's classroom is awash in the sudden sobs of children. They form a single file line at the door and await the lead of Mrs. Livesay; the author of this story and his classmates cry into each others' spines, trembling.

The timelines consist of photographs describing a line of time. And on special and long paper. The author of this story will get a less-than-satisfactory grade on his.

Through a speaker, the principal: "This is not a drill."

This is a drill the author of this story and his classmates don't know.

Outside, there is April or May, scents many and sweet, an easy breeze, but the author of this story and his classmates know how the weather stirs from this still, might suck up any spring day with the right confusion of cool and warm airs.

In the author of this story's timeline, Mrs. Livesay will take off points for a lack of specificity, in general.

"But the dates of the photographs?" she will write.

There are no alleys in the town where the author of this story and his classmates live. Too few buildings. Too much breadth in all its views. Not enough spots that block a looking at the long flat pourings of the land. The author of this story dreams alleys as statewide swaths of open plain, inviting a hell-swirl from above.

Mrs. Livesay does little to calm the author and his classmates' demand for their mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers and pets in the long line at the door. To be held and to hold. To be with. To sob more comfortably into than their peers' small spines in the line. To hear a better tale of it. To save the mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers and pets from the peril they might face from without because the school is big and on a hill.

Left to right along his timeline, the author of this story in a highchair will come after the author of this story swaddled still in hospital linens, red-headed and wrinkled.

And this is accurate.

But as to when these pictures of himself are, Mrs. Livesay will say the author of this story has said nothing.

There is no savage wind of utter dislocation spinning outside to pluck them away, forever, and as the line they form peels out the door, the author of this story and his classmates scream on for their mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers and pets to die with and the whole hall gives echo to both their form and contents. In lines of 20 that break near classrooms' doors, the author of this story and his classmates and the entire school stand third bricks from the wall and stare into weird mirrors of their own red faces.

Finger-like is the simile given to the author of this story and his classmates like a warning in a book they're read on tornadoes' forming. Like an omen. Like a promise in a book they're read. Like a sign to find along the stretched horizon telling only their imminent obliteration.

The author of this story dreams funnel-clouds as so many hands' single digits pointing precisely to all the things they'll tear to shreds.

The line of photographs describing the author of this story with blonde hair comes after those of the author of this story as a newborn, after his crawling, comes after his standing with the aid of the coffee table with red-hair. And the darker hair of the last photographs and today comes after the blonde.

But, in so many words, Mrs. Livesay will say the author of this story's failed to locate the points along his timeline. In so many words, she will circle the lack of months, of dates, of years, along the line of time the author of this story's photographs describe.

The author of this story and his classmates pray and cry and make small balls of themselves; sweated palms grip shaking knees, all atremble, not wanting to die and longing to be underground.

Coming after whatever is the last photograph along his timeline, the author of this story will not include a photograph of waiting to die in the hall with his classmates. No one takes a picture, and there is not a tornado outside. Nothing's outside tearing already at their edge as they await the coming of what they're sure is after them.

Before the author of this story and his classmates are the wall and the floor and their own bodies and the prospect of ending. They dream the green of the light through the clouds that is not outside.

Outside, there is blue-sky and the author of this story and his classmates know that before the path of a tornado there is little hope.

That less comes after.

That surviving can only be a story of looking, relentlessly, for where everything's gone.

There is not a tornado outside unwriting the long stories of trees, unwriting the springs' sudden blooms, unwriting points of reference within the town and turning it to an intimate unknown.

The author of this story and his classmates are eight, are nine, and curb the short lines of their bodies, return to the crouchings of the womb in a line of 20 against the wall, run their sobbings into themselves. Their chins slip in the salts and snots and waters of their bodies along the small lines of their clavicles and they prepare for the tornado that is not outside to arrive.

The author of this story and his classmates hold their breaths.

In a book they're read, they hear it sounds like a train.