|

|

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Nonfiction |

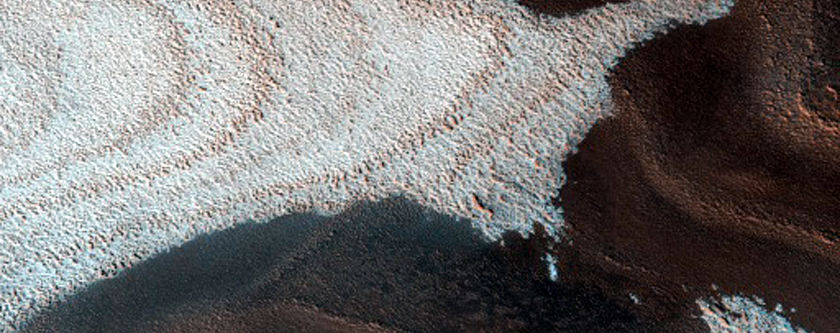

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

"Do you know where we are?" the sheriff asked me, with a sideways glance, turning off the ignition. He probably knew I had no idea. "We're near the village of Cañones. This is where we start looking."

Several hours before, Emilio Naranjo, the sheriff of Rio Arriba County, New Mexico, had told me what we were looking for—a dead man.

I was a young faculty member at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and had traveled to Northern New Mexico so that I could help at a small clinic in the village of Tierra Amarilla while the clinic's regular physician was away.

He had knocked on the door at about one in the morning, a middle-aged, sturdy presence in a snow-covered cowboy hat. He apologized for the early hour and the snow he'd tracked in. "Did they tell you you're also the medical examiner for the county?" He nodded in agreement before I could say, no, they hadn't—"and we're going to look for a body."

It took two hours to drive 40 miles—the only car on a snow-packed descent through piñon and juniper canyons, past sentinel rock faces in half moonlight.

We parked along a narrow road at the mouth of a canyon. "I think he's over this mesita," Sheriff Naranjo said, and I followed him, trudging through snow a foot deep, over a small ridge and down to an arroyo. We walked 50 yards or so, and he was there, outlined and snow-crusted like a rocky intrusion, a white masked face, arm across his chest, across his heart. We both knelt down and with a gloved hand the sheriff brushed the snow away from his frozen face. There was a bullet hole right in the middle of his forehead.

I was wondering what a medical examiner would do, and I remembered from a medical school pathology lecture that he'd look for the Mortis brothers, Rigor and Livor—rigor mortis, the stiffness of the body, and livor mortis, the dependent purple stain of blood, pooled and layered like some geologic stratum. He was already frozen stiff, his thin jacket a sheet of ice, and as I tried to pull it up to check for livor mortis at his waist, Sheriff Naranjo looked at me quizzically. "Doctor—do you think he's dead?" He chuckled, and perhaps I did, too. I remember thinking I'd never seen anybody more dead—but I figured Sheriff Emilio Naranjo probably had.

There was no crime scene investigation—at least not then, and I somehow doubt ever. We picked him up, a frozen, dead weight, and carried him head and heel as if he were a stretcher back to the police cruiser. And then we slid him feet first along the back seat, angled down so he would fit, and drove him to the Española hospital.

The next night, Sheriff Naranjo knocked on the door about midnight. There had been a shooting at the bar, and the victim had been brought to the clinic's new emergency treatment room. I remember seeing spurts of blood as I hurried to the man on the gurney. He'd been shot in his scrotum. We were able to clamp the artery and get an IV started, and then we loaded him into a Chevy van that had been converted to an ambulance, and once again we drove to the Española hospital. Our patient survived, but a friend told me years later that the man's cousin, who had shot him in the balls, shot him again, this time in the heart.

Rio Arriba County is larger than Connecticut, a starkly beautiful land of mountains and river valleys. Its first settlers were the ancestors of the present Pueblo Indians, and in 1598, the conquistadors arrived. The Spanish explorers' journey along the Camino Real, the royal road from Mexico City, ended in what is now Española, the economic hub of the county, a town of 10,000 on the banks of the Rio Grande. The settlers called the northern, upper course of the Rio Grande River and its territory the Rio Arriba, and below Santa Fe, the Rio Abajo.

There has been a struggle for land and power in Rio Arriba for hundreds of years. Utes fought the Comanche here, Apaches the Navajo, and the Spanish Conquistadors fought everyone else. The Spaniards, and later, the Mexican colonists who came to New Mexico, claimed the land that they could in the names of a succession of Spanish kings. Oftentimes, multiple families shared the same land grant in common, and they treated their lands as a commons, raising sheep and cattle, cutting wood, and farming, work that barely sustained them. In 1848, the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican American War and ceded the New Mexico Territory to the United States, also assured the overwhelmingly poor Hispanic settlers in Northern New Mexico that they would retain ownership of their land and their grants. It didn't happen. Between unscrupulous Anglo land barons, railroad land grabs, and unsympathetic courts, Northern New Mexicans continued to lose their land and their many appeals for justice.

Northern New Mexico has remained a frontier—an isolated, beautiful, but hard land that seems visually and palpably unique. Historically, people who live on frontiers often endure poverty and stress; there tends to be more alcohol and drug use... and violence.

I continued to work in Rio Arriba's high mountain villages, helping communities to organize clinics, bringing medical students and residents to help staff them. The distant descendants of Spanish explorers and more recent arrivals have been my patients and my friends over the years. I've cared for the diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and chronic pain of these hard-working farmers, ranchers, and tradespeople of Rio Arriba, and many years ago, I treated a heroin abscess, festering square in the belly of a tattooed Virgin of Guadalupe on a patient's forearm. Several months after that, I arrived in a mountaintop village clinic to discover that its young physician had been found dead, slumped in a chair, a needle dangling in his arm.

Learning and practicing medicine is about pattern recognition, identifying the distinctive trails of histories and the symptom clues of diseases, recognizing a class of coughing children, a woman's bruised face, chest pain radiating down an arm, a needle's tell tale tracks, the smell of alcohol on a breath, or, in my case, a community newspaper's reporting.

Returning from our clinics, we would drive through Española late Wednesday afternoons, and there were inevitably traffic jams. Española is known as "The Low Rider Capital of the world," and frequently traffic would back up behind a parade of vintage cars, like a '55 turquoise and cream Chevy I remember, raked and lowered, doing ten miles an hour in a 35 zone, bass note bouncing with a $5,000 hydraulic system.

But I realized it wasn't just low riders causing the Wednesday traffic jams. People were slowing down to buy the Rio Grande Sun, Española and Rio Arriba County's weekly newspaper, hawked on the small town's busiest intersections. I stopped to buy copies, and eventually I started subscribing.

The Sun was consistently winning awards for investigative journalism, its reporters filing multi-part stories over weeks or months, covering a county where I began to appreciate that political shenanigans and local government malfeasance were the rules, and violence the norm. The Sun campaigned for open meetings and records and wasn't afraid to sue if it was stonewalled. And of course, the Sun also covered crime, and reading it, I began to realize that my first two days in Rio Arriba County seemed almost routine, that there were inordinate numbers of murders, robberies, DWI and domestic violence stories, and for a rural community that I both loved and lived in, the Sun's police blotter was a weekly study in social dysfunction.

Bob and Ruth Trapp were both young reporters when they started the Sun in 1956. For almost 60 years, Bob Trapp had been the quintessential small town newspaperman—the last of a vanishing breed—a scrupulously honest, fearless, independent journalist and a mentor to generations of young reporters. Bob died in 2014, but his son, also a Bob, continues the family tradition.

Forty-thousand people live in Rio Arriba County and it's estimated that 30,000 read the Sun every week. It is passed around in families and between neighbors, and its local news is interpreted for the Spanish speaking elderly and recent Mexican immigrants. If lawyers from Santa Fe and Albuquerque need some information, some background perspective about their cases, they read the Sun. The Smithsonian Magazine once asked rhetorically, "Can a weekly paper in rural New Mexico raise enough hell to keep its readers hungry for more, week after week?" The answer is people love it, and hate it, but nearly everybody reads it, including, presumably, the dozens who have contributed to the rock-through-the-window collection displayed prominently on shelves around the office, and most recently, the person who threw a modified Molotov cocktail—an entire gasoline can—through a window. The fire was contained, the presses rolled, and the understated story only made page three.

I soon realized I was reading about a pattern—the signs and symptoms of an endemic health problem, reported not by the medical community, nor the county or state governments, but by a community newspaper. And apart from a few voices, no one else seemed to pay much attention—until 1999. That's when the Sun broke the national story that Rio Arriba County had the highest per capita heroin overdose rate in the country. Fifteen years later, it still does. And Rio Arriba County invariably leads New Mexico, which usually leads the country, in almost every category of public health risk: prescription drug overdoses, domestic violence, homicides, DWI's, and suicide.

The Sun has kept on the case. Every year it prints a summary, a one or two paragraph vignette about each overdose death—their names, ages, and the medical examiner's toxicology and autopsy findings. It's a descriptive diorama of a death scene; of how they were found, a needle left stuck in a vein, a bottle of spilled pills by her side, and an empty pint of vodka in his back pocket. They are obituaries without the family and friends or instructions about where to send the flowers.

There is no unifying theory as to why heroin, other opiates, and alcohol invaded this very rural place and its people. Various hypotheses include Vietnam vets returning with habits, conductors and porter pushers on trains that used to stop here decades ago, and Mexican mafiosos and gangs peddling so-called black tar heroin far off the interstates, along the rural, blue highways of Northern New Mexico.

For many of my patients and their families—whose resistance has been worn down by poverty, racism, depression, and violence—the modern derivatives of the opium poppy, along with alcohol and family dysfunction, have devastated their lives and their community like an infectious disease, spreading between generations and by contact with contiguous neighborhoods.

In 2003, the World Health Organization defined "The Social Determinants of Health," "the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age," and the forces that shape people's environments like economics, social policies, and politics. The social determinants include health behaviors like alcohol and drug use, smoking, diet, and exercise; social, economic, and environmental conditions like employment, education and family support; and access to quality clinical care. They are the things that really matter in our lives.

Every week, in the Sun, I can read about many of those social determinates, and the policies and politics that shape them. They are the news, the headlines: the millions of dollars that came to the county for drug and alcohol rehab programs only to be squandered through mismanagement and cronyism, and now the programs are gone; the failing schools with a 56% high school graduation rate, and seven different Española school superintendents in five years; the lack of community leadership, vision and jobs, and the paucity of social support systems.

Bob Trapp said, "A good community newspaper is like a library. For many communities, you can go back and see what happened a hundred years ago." Newspapers are not in the public health business, but I think good community journalism provides an important cultural context, a social history of place and people, a backstory that can help in assessing a community's health. But, along with the demise of the paper health record, newspapers are going away.

If you can't read about your community's health in a newspaper, thanks to the University of Wisconsin Center for Population Health, you can see a digital diagnosis of its health status on a map, zip code-specific. The social determinants of health is a mouthful, but its well-researched health behaviors and conditions frame an interactive model that ranks the health of every county in our country. You can look yours up, compare it to others, and even see how to improve your community's health.

On the health rankings website, Rio Arriba County ranks 31st in New Mexico, next to last. Ironically, Los Alamos County, just up the mountain from Española, and the site of the Los Alamos National Labs, ranks first, the healthiest in the state. The fact that neighboring counties can have such great health disparities is further proof of the differences that race, income, education, and geography make—that your zip code may be as important as your genetic code.

Still, the website won't tell you the history of your place—the backstory—that a good newspaper can.

At the time, the violence I encountered long ago with Sheriff Emilio Naranjo seemed an unlikely, random occurrence. It was a good story I could tell. Perhaps, the story became a little more embellished after I began reading about the county's problems in the Rio Grande Sun—that, and following Emilio Naranjo's colorful career. While sheriff, he was accused by a political opponent of planting marijuana in his truck, and then convicted of perjury (although the conviction was later overturned). He became a State Senator, and ultimately, the Patrón of a political machine that controlled Rio Arriba County for 30 years. The story might even get better, if I'm telling it on the winding road leading to my home in a beautiful canyon—and, timing it just right—I point out the place where Emilio (as I fondly call him) and I parked that night to find the dead man.