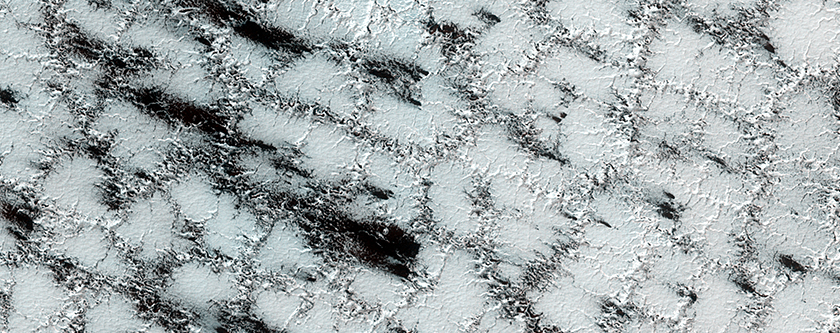

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

The day you forgot to put the chicken in the chicken stew, I knew we had a problem.

Where the hell's the bird? I said.

You laughed.

I raised my hands and shoulders and eyes to the heavens.

You said, What?

I grabbed the marker by the Ocado grocery board. Where's your hearing aid? I scrawled. You wrote SMASHED. I wrote SMASHED? You underlined your version twice with a flourish. I added two extra question marks to mine. You yanked me in and plopped a kiss on my forehead. I stood there with my breasts squished to your chest. You said, What's the matter with you?

I shrugged.

Let's watch something cheerful. Let's watch a Jamie, you said.

We ate our thin stew out of soup bowls in front of Jamie Oliver's Food Escapes. It was the episode where Jamie goes to Sweden. I didn't mind watching it again, subtitles on, volume way up, because I enjoyed your surprise at Jamie's reaction to the world's stinkiest fish. You guffawed, and I laughed along with you.

After the end credits had rolled, I said, Do you remember our summer in Fez? You said, Yes! I said, We ate pigeon pie sprinkled with castor sugar. You glanced in the direction of our newly acquired birdfeeder. I said, How about Vancouver? Do you remember that? You said, Mm. I said, Remember the restaurant we ran back in the thirties? elBulli? Up on the hill? Yes, you said. Yes, I remember. Nice place. Good view. WE NEVER HAD A RESTAURANT, I yelled. IN THE 30s WE WEREN'T YET BORN! I WAS JOKING, TOO, you yelled back.

I sulked, then stared pointedly at your bowl. Didn't you like your chicken stew?

You scowled. Things these days don't taste the way they used to, you said.

I took our trays to the kitchen so you wouldn't notice the tears in my eyes. The Eating and Drinking Factsheet lay open on the counter. Food wasn't supposed to be a problem at this stage, but last night you'd prodded your cottage pie as disdainfully as if I'd piled smouldering garbage on your plate. You wrinkled your nose; you pushed it away. You, whose love of cottage pie was legendary. You'd never eaten less than three helpings of mine. Your refusal to try even a spoonful was a step backwards. No, further: it was a step off a cliff.

The Factsheet said, "Food tastes may change so experiment with stronger flavors." It said, "People may show a preference for additional sugar or salt." At the bottom, it said, "Damage to specific parts of the brain means some people may enjoy tastes they never liked before or dislike foods they liked previously."

I'd contained my panic over the meal last night but only just. If you were tumbling down the timeline of your life—and sure, it wasn't like that, not quite, not all at once; it was an uneven slippage depending on mood and sleep and other less predictable factors—and you remembered me still, definitely, no doubt about that—nonetheless the question gaped: how long before I would be cottage pie?

Every day I tried to be upbeat. Every day I failed.

In every conceivable way we seemed to be headed in opposite directions. You were eating less, I was eating more; you were growing thinner, I was growing fatter; you were living happily in the moment while I was in an almost constant state of fear about loss.

It got worse.

Just as alcohol does not bring out a person's true nature but rather a version of it, said the doctor, so with dementia. A kind person may become nasty. A prude may become an old letch. A generous person, mean... You, my love, were consistently kind hearted. Optimistic in a way you would once have mocked. Soppy, sentimental, no longer discerning. You, who had previously dressed in Marks and Spencer's blues and greys and blacks, the nautical range or the Italian, bought yourself a camouflage onesie. For special occasions, you told me at the time.

It wasn't that I minded your eccentricities scooting out in public. I didn't give a hoot what others thought. But losing you, I minded very much. I minded not being able to talk to you about what was going on. I minded decades of our memories slipping so bloody indiscreetly away. I minded how I was not even supposed to show you I minded. Perhaps that was what I minded most of all.

The doctor had spoken of possible changes to your nature, but he hadn't mentioned the possibility of changes to mine. Yet, changes there were. Oh, yes. For every sweet craziness you showed, I became more crusty, irritable, blaming, abusive, erratic, pessimistic, helpless to suppress my ire, and filled with self-loathing.

So, what to do about it?

The doctor said I must fit myself to your reality. No vice-versa possible. But I didn't want to fit into your present: I wanted our presents to coincide. That, my dear, said the doctor, is like wanting to bend time.

Then, I decided, we must bend it.

On the grocery board, I made a list. Time-bending experience, I put at the top. Underneath, I wrote: new, shared, totally consuming. I added sensory. Then I paused. You were too deaf for music. I couldn't control where you looked or what you saw. Taste would've been the obvious choice before—then there was smell. A new smell? A combination of taste and smell? Stronger flavors, more salt?

I ran to the study to boot up the computer. Was the world's stinkiest fish available here? Yes, Google answered. My heart thudded like a fresh catch on deck as the tin of surströmming appeared. One item in the basket. Click. Basket to checkout. Click. New tab. If you got rotten herring on your clothes, said the online forums, you'd want to dispose of them. What better clothes to try it in than onesies? I ordered another camouflage number for you and two in my size. Then, some Swedish tunnbröd. Despite being able to get potatoes, onions, and sour cream over the road, I ordered them from the Swedish shop, too. This online shopping was a riot.

After I had made sure each order would arrive before 9:30, I planned a trip out of town. The traditional way to eat the fish was in the open. If we didn't want to draw attention to ourselves, it would be best to do it far from the crowds. I gazed at my screen. It wasn't quite Sweden, but it had the water and the mountains and the remote, open space; Jamie would surely approve of surströmming in Wales. I bought two train tickets to Aberystwyth. From the station we'd get a taxi to a secluded spot. By my calculations, we'd be at the beach before sundown.

Order, regularity, routine, said the other factsheets in the series, but I didn't see how that was doing us any good. Fight madness with madness, I reckoned. We'd make a new memory with a smell that would stick. With the world's stinkiest meal, we'd blow our senses apart. Together. If we hated the experience, if we puked, well—YOLO, as the youngsters online put it.

First, came the courier with the can of fermented fish, the tin red and yellow and swollen and rusty. Next, came the courier with the package of onesies. Last, came the man from the Swedish shop with the fresh Swedish groceries.

The trip was six hours, door to sea, though I'll skip the details of our journey. The difficulty in doing something unpredictable could have been predicted. Suffice to say, while I was used to your disease's almost tidal fluctuations, your slip-sliding away seemed to skid ahead rather alarmingly—but come, let's skid ahead ourselves to the part where the taxi driver dropped us off at the beach.

The sun was sinking against a livid sky. Starlings were swirling in ever bolder patterns above the pier. The sea was green and calm.

You stood, your face slack, your expression not empty but entranced.

I stood next to you, and I suppose I could have modified my silly plan and let you be, but I chose to force things onwards.

Sweetheart, I said, time to eat.

You ignored me, though I knew your hearing aid was not smashed but wedged like a mollusc in your ear.

I spread our green and blue picnic blanket on the grey pebbles. I laid out the ingredients for our surströmming smorgasbord. When everything was ready, I called to you again.

You said, I'm not hungry.

I said, 'Course you are.

Shhhhhhhh, you said.

I pulled you over to the blanket. I forced you to kneel down. Your head remained lifted, your eyes in the air.

Have you ever seen anything so beautiful? you said.

Many times, I said.

Don't you like birds? you said.

Not as much as fish, I said.

No, you said, no, I like birds.

I knelt alongside you with my automatic can opener. It was time to take the bloated tin in hand. I clamped the rim and pierced it.

There was a hiss.

You jerked away as if you'd heard a snake.

I laughed. Have a whiff of this, I said. I called out, louder, again, to you and the beach and the ocean and the heavens and the birds, HAVE A WHIFF OF THIS.

It was then the smell hit.

We retched convulsively.

Jamie had underplayed it. The words used to describe it online—humid rotted burning rubber faeces roadkill dumpster—fell short. Revolting: our bodies were revolting. I kept my finger on the opener until the top of the can fell off. And then, vile and putrid as the stench was, it began to edge towards bearable.

Our retching stopped.

I wiped the blur from my eyes. I was giggling. Hysterically. I thought you were, too. I passed you a roll of kitchen towel, grateful I'd packed us one each. My hands were shaking, but I was determined not to be like the fools on YouTube who treated the food as a prank. We would do this properly. We would show the traditional ritual its due respect.

I cut two small squares of the crispy tunnbröd. On the top of each I placed a smear of butter, a teaspoon of crushed almond potatoes, a scoop of sour cream, a sprinkle of the finely diced red onions and, the pièce de résistance, a sliver of fermented pink herring. I held a morsel as pretty as sushi out to you—and found you were crying.

Love, I said, trying to laugh your tears away, there's nothing to cry about.

But you only sobbed more. You said, Something's died. Something's dead.

I pulled you away from the picnic blanket. With the morsel in one hand and your wrist in the other, I dragged you, weeping, across the beach.

Dead dead dead, you moaned.

When we were as far away as we could get, determined to carry out the rest of my plan, I shoved the morsel into your mouth. It smeared on your chin. You spat.

Disgusting, you said.

Delicious, I said.

Then why don't you try some yourself? you said.

All right, I said. All right then, I will.

I turned back to our picnic spot, but the tin was no longer there. Nor were the starlings. Overhead, rogue seagulls were fighting. Something fell into the ocean with a splash. At once the birds went back to the basket for the rest of our meal.

Everything gone, I thought to myself. In the end, everything's gone. There's no way around it.

Smell might not have brought us together as I'd intended—but we were certainly together in being kept apart from everyone else. The taxi driver refused to take us back to the station, but to give him his due, he arranged a lift on a farmer's cattle truck. On the train, we had the whole carriage to ourselves. And on the tube, the last one of the night, it was pretty much the same.

After we had disposed of everything related to the experience in the bins outside, we took a long, hot shower together. I hosed you down with Fairy liquid, then you hosed me. We took turns; it was fun. The detergent made brilliant, pine-scented bubbles. When we were done, smelling like two fresh dishtowels in our spare, clean onesies, we settled down to watch a Jamie's Food Escapes.

Halfway through the Andalucían episode, you got up from the sofa.

Don't pause it, you said.

Sure I will, I said, pressing pause.

No, you said. I've seen this one.

I raised my eyebrows. You shuffled through to the kitchen.

Shamelessly, I pressed my ear to the partitioning wall. I heard the grocery cupboard open and shut. I heard the lid come off and go back on the biscuit barrel. I heard rustling in the bread basket. I hesitated, then called, There's some leftover cottage pie in the fridge.

Want some? you called back.

If you are, I said, nonchalant.

You returned to the sitting room bearing two hefty helpings on a tray. Okay, they were served in coffee mugs, yours with a salad spoon, mine with a mustard spoon, but still. I clicked pause again to make the episode continue, but I couldn't eat. My eyes were on the screen, but my attention was on you. Finally, able to hold back no longer, I peeked. You had your mouth to your mug, literally shovelling the food in.

Hungry? I said.

Umgtphshwyes, you said, talking, chewing, and swallowing at the same time.

Two nights ago you wouldn't touch my cottage pie, I said.

The moment the words were out, I regretted opening my big trap, but you simply shrugged.

Leftovers are best, you said. You know that, love.

Huh, I said.

I stuck my teeny spoon into the potato crust, then changed my mind. Taking my cue from you, I lifted the mug to my mouth and shovelled.