Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

It's dry and hot, 95 plus. Kay has pulled her car off the road and is walking the gravel lane following the eastern edge of Sugarbush Lake. Her dog, a yellow mutt called Sally, darts in and out of the woods. By high summer here in western Michigan, the trees and undergrowth are dense between the lane and the lake. When Sally finds the shore, she leaps into the water and paddles in a small circle before racing back to Kay's side to shake herself dry. Kay is a place, too.

Cold, wet dog spray reaches Kay's bare legs and the hem of her cotton skirt. This makes her jump a little, but the spray feels good in the heat. "This water finding my skin is Sugarbush Lake," Kay tells herself. Sugarbush is where she spent summers as a child, a few snowbound Christmases, too, and where, one July, she nearly drowned. She still looks up the word a few times each year. Kay says we neglect our important words. So, this word drown: to die under water or other liquid of suffocation. Traceable back to about 1300, as a derivative of the Old English druncnian, "be swallowed up by water" (originally of ships as well as living things), probably from the base of drincan, "to drink." And there it is, Kay thought, when she first read that: we drink to live and we swallow; we are swallowed by what we drink.

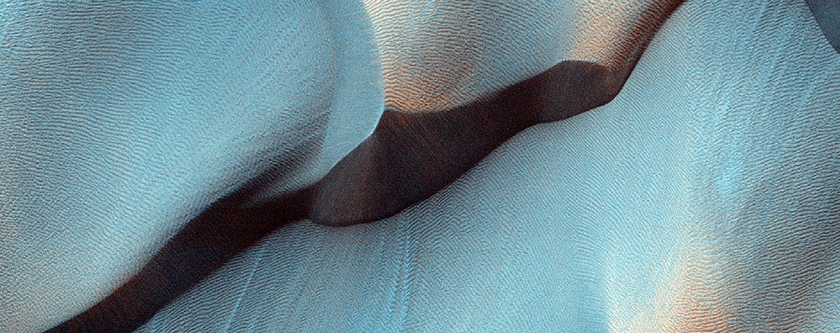

Here is the lake, outlined in blue in the top right section of the map:

Sugarbush is life. Life is the shape and geography of the lake, its soundings—the latter, a nautical term. We take soundings by dropping a line in the water to measure its depth. Sugarbush has the irregular contours and nebulous waters of a fetal sonogram. The sonogram a sounding, too. Ultrasonic waves are above the range audible to human ears. These are waves before birth and after death. Sugarbush is death, too. This same water once opened its mouth and pulled her under. The swallowing lake.

Kay is nearing the cottage where the family used to stay, but she is not in a hurry to reach it. Nor is she in a hurry to put her toe in the shallows at the lake's edge. She aims to pull time off its mission, make time into something belated, a train losing minutes as it heads for the station. "Move slowly, Kay," she sings aloud to herself, her voice like a bell, her voice ringing a few feet above the lane before slipping into the air and woods. "Move slowly! Move slowly!" She's not young anymore. Sixty years have passed and will disappear. She no longer has all the time in the world. She remembers the impatience of childhood, how she fought to speed the deliberate clocks and calendars. When will the school bell ring? When the summer holidays? When Christmas? She could weep for having rushed the hours, for all the now-times spent dreaming of future-times.

Today, the weather is on Kay's side. A summer slower than molasses. The air is still, nothing stirs, no breezes come off the water. Only hot sun on her back and glinting off the water's grey-green surface. She hears the dog at play and insects buzzing. No other voices but these, and her own. The people who brought Kay to this place, season after season, are gone. In the graveyard. Mother, father, grandparents.

Finally, more than halfway along the lane, Kay reaches the cottage where the family used to stay. There are no cars in the driveway, no people on the familiar deck with its stone barbecue and picnic table. On the side rail, there is no transistor radio, a baseball game in a box, snapping the afternoon. These cannot possibly be the same barbecue and table she remembers. Yet they appear to be. Here is a view of the deck looking back towards the lane:

Look closely. Kay is there, but difficult to see as she stands in the wash of bright sunlight, an open field behind her.

Kay remains at the edge of the property for a long while, wondering what to do. Finally, she moves past the barbecue and steps onto the rust-red boards. She pauses to check whether her footsteps have disturbed anyone inside the house. Will the door be thrown open? Will someone smile and say, "Can I help you?" or "Are you looking for somebody?" Or "Kay, we've been expecting you?" Or will a nervous owner step out and demand, "Whadda you want?" "Who are you?" None of this happens. When Kay finally musters herself forward to tap on the door, no one comes. While waiting there, she thinks about mustering—muster in, muster out, mustering troops, mustering courage. It is hard to warm to people who show no need of mustering. She likes clichés. She likes an explanation given by filmmaker Terrence Malick, back in the 70s: "When people express what is most important to them, it often comes out in clichés. That doesn't make them laughable; it's something tender about them. As though in struggling to reach what's most personal about them, they could only come up with what's most public." Thank you, Terrence, Kay says now and again. Thanks because it is not easy to describe ourselves.

She taps again, but the place is closed tight. No movement or voices within. Odd at the height of summer. Relieved to be there with only Sally at her heels, Kay peers freely into the cottage to note how little has changed. The same pine interior, same row of picture windows overlooking the lake. She recalls the wire mesh window screens they put up every summer to soften the sunlight, cool the rooms, and allow in the odors of pine, wild flowers, algae, and rusted rowboats. She recalls, too, one December evening, standing on the long sofa beneath the windows, elbows on the ledge, face pressed against clear glass. Her mother turns off the lights, leaving only the fireplace to throw sparks and shadows, so they might watch the storm. Snow is falling, a blizzard so fast and thick, Sugarbush Lake is a whiteout. Lake Michigan, less than 50 miles due west, surely a whiteout, too. The Great Lakes are disappearing.

By the time of the blizzard, Kay has come to prefer winter over summer, especially at Sugarbush Lake. They cannot press her to swim in December. The problem might be set aside as long as snow falls and the days remain cold. But spring comes and summer will not be stopped and soon they start in on her again. First, her mother takes her shopping for a new swimsuit and talks up the Sugarbush vacation. This is confusing to Kay, who loves shopping with Mom in the brand new suburban malls near Detroit, who loves Sugarbush and the cottage, but is now afraid of the lake. In the weeks before going, she lies in bed at night and imagines it, this water shaped like birth, a life-giver, its surface lush with lily pads. But for a frightened child, the idea of life does not bring comfort. Life is alarming, dense and dark. Trees from ancient wilderness press the lake's edge.

Her fear is made worse because she cannot remember going under. She knows it happened. As a fact, an incident. The near-drowning incident. It has entered the family annals, become a narrative, an explanation even, of a child with too many fears. But often, our memories are only what people say happened. And these are constantly revised as they pass from one person to another, one year to another. For example, sometimes, they tell her it happened to her at the age of four. Sometimes, the age is five. Sometimes, they say "now what year was that?" As if the event is receding in importance. As if they are trying to trick her into forgetting it. Into forgetting what she cannot remember.

Kay dislikes relying upon the word of others. But she possesses no auto-narrative of the event, no immediate knowledge or representation of it. There is only a sensation of pulsating dread when she thinks about the water. Her sister says "picture yourself swimming strongly all the way across the lake." Kay closes her eyes. But she cannot shift herself out of the shallows and into the middle. The best she can do is put her mind at the shore. She imagines the lake's edge, moves her mind along it, until finally, here and there, she comes to an old ramshackle dock:

These homemade docks at Sugarbush, promising firm ground, a stone path leading to a cottage, a mother and father, a clearing in the trees, and a gravel road back to town, because life asks to be lived.

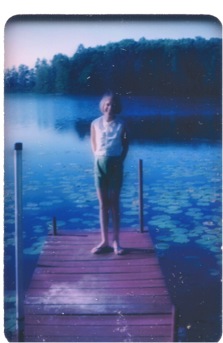

Here, taken during the time of her fear, is the only remaining picture of Kay at Sugarbush Lake:

She must be about ten years old, so this would be several summers after the near drowning. A new haircut, summer shirt tucked into her shorts, a little tummy and below it, skinny legs ending in rubber flip-flops. To prove to them all she is carefree, Kay runs almost to the end of the dock with its loose boards and creaking supports, before turning to pose for Dad with his Kodak camera. It was Dad who pulled her out of the lake. Now she clasps her hands behind her back and smiles. No one should guess how lonely and humiliating it is to be cut off from the others when they swim and splash and dive and dunk.

Kay keeps the photograph of herself at Sugarbush because it is the only one and because as an obsessive archivist, she must. But she cannot bring herself to look at it very often. She knows fear is not pretty, not appealing, and fear is present in the photograph.

By the time Dad snaps this picture, Kay has become a timid swimmer who will no longer venture beyond her footing. Every year, they remind Kay she once was happy in the water, happy and fearless as her mother has always been. Mom grew up on the banks of the Thornapple River and all the local lakes. Mom swam every day of summer. Mom was a fish. Although she too had a water incident. At the age of 15, she swam under a raft to hide from her brother, got trapped and could not find her way out. Many times, Kay has heard her tell the story, even detected a trace of panic entering the telling. But no one has found a helpful way to connect what happened to Mom to what happened to Kay. If anything, the mother's incident makes it worse for the daughter. Mom was brave where Kay was not. Mom found her way out; Kay had to be pulled out. Mom got back in the water and kept swimming, whereas Kay... In sum, Mom's incident is a story of overcoming, Kay's a story of defeat, one more thing to feel bad about. Families fail to notice the narratives in their midst.

In fact, Kay has no memory of being fearless in water. It's gone. Various remedies are tried during the remaining years of her childhood. Lessons, encouragement, carrying her into the lake, coaxing her to swim alongside her father. There are painful humiliations, too, as her parents grow exasperated with a child so focused in her terror, so grasping of their arms. One night during a family trip to the Smoky Mountains in Tennessee, they check into a Holiday Inn. Her parents decide to give her a swimming lesson in the motel pool. Kay cries and clings to the step ladder at the pool's edge as her father beckons her into the middle. Eventually he gives up, swims past her and climbs out of the water, a cross expression on his face. Wet with shame, she climbs the ladder behind him. From a safe distance, she watches him confer with her mother. The pool lights dance, animating her parents' heads bent together in discussion of their youngest. Their disappointment and embarrassment radiate to where Kay stands, chlorinated water running down her bony, shivering legs, to make a little puddle on the Holiday Inn patio.

Progress is slow, but progress is made. At the age of 16, many lessons and attempts later, Kay begins to go into the water alone and gradually recovers a limited pleasure in swimming. When summer comes, she wades into Sugarbush and breaststrokes away from the shore, turns on her back to tread water and stare at the sky. But with each swim, Kay is hyper-vigilant, constantly drawing the invisible line beyond which she will not go. As long as her feet reach the lake bottom and her head remains above the surface of the water, she is on the safe side of the line. She swims a few yards at a time and tests the bottom, relieved to find it. A few yards more, test again. Until she reaches the spot where she must stand on the tips of her toes to reach the bed of the lake, or the moment she feels herself carried by the water's currents.

Only once in the succeeding years does Kay misjudge her footing in the lake. It happens during the last summer spent at Sugarbush, not long after the birth of her son. Kay brings her husband and baby to Michigan, and her parents rent the cottage for a month. The first afternoon, she leaves the others sitting at the picnic table up above the shore. She goes down the path, tiptoeing from stone to stone with her bare feet, then places her towel on the dock and wades into the shallows. It is early summer, and the water is cold, so it takes many minutes before she is in up to her waist. With each step, the water inches higher and Kay shivers and lets out an ooooooh. She hears them laughing up at the table. She laughs with them. She turns to look back at her son, a baby in her husband's arms. The adults are talking now, not watching her. She is alone down here. She eases herself in and glides away from the shore, thinking about her son. How tied a mother is to a son. How connected to the land. She swims gracefully, her body made tired and lazy after nights of broken sleep. Her mind full but unfocused. She forgets to test her footing until she has drifted too far. She turns upright in the water so her feet will find the lake bed, but the bed has dropped away, leaving her suspended. Kay's body and head bob below the surface. She goes under momentarily, comes up spluttering. The panic of childhood returns with terrifying speed, as if it has waited too long. Kay coughs and thrashes and fights for the shore. In less than a minute, she can see the shore is nearer. She is swimming. She propels herself several yards further and then tries for the lake bed again. There it is. Her feet find it. She stands, water at her shoulders, catching her breath and watching the people at the picnic table. They have not seen. She will not tell them. She swims back slowly, allowing time for the fear to recede. Kay reaches the dock, wraps herself in the big towel, climbs the stone path to the picnic table and sits down to warm herself in the sun. Next to the living.

Now. Today. Parents dead. Husband gone. Son grown. Sally will die soon. Kay never knew a dog that didn't die on her. Kay has come here to remind herself how once she nearly drowned, and although it took many years, she learned to swim home. She wants to remember she did swim home. By herself. With that knowledge, she can sit on the dock.

This will be Kay many years from now, an old woman at Sugarbush Lake, and in this photograph, there is no fear:

Sometime after this photograph will be taken, when she is too frail to swim and memories are going, when there is no reason to fight for the shore, Kay will find the near-drowning incident of early childhood has been in her mind all along. Soon it will be the only thing in her mind. A memory of how to die. You drift out beyond the imaginary line, until you can no longer find your footing. And let yourself go under.