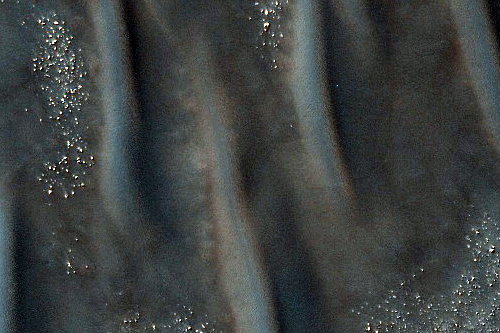

Image: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

The large woman stepped into Swee Heng Cakes and Delicacies on a hot morning with her two children: a ten-year old boy who reproduced her rotundity on a smaller scale and a six-year old stripling so pale and skinny, the market aunties did not believe he was her own. She was not feeding him enough, that was obvious. He walked too quietly and docilely at her side for a child his age. Maybe she put something in his food, drugs or something, they said, looking at the dark circles under his eyes. But the market aunties were too delicate to say this: he was going to die.

Under sheets of sticky plastic held down by metal clips from Popular bookstore, gleaming buns sweated and butter-cream cakes lay tessaracted where the baker's knife had just passed. First customer of the day. Mother who starves her son. He flicked away the last bit of grime he had picked from his toe nails and stood up with a grunt.

On her full moon face was a half-moon smile between long Buddha earlobes—a smile to be found on nurses and Chinese teachers of a certain generation. It was an old-fashioned face. He scratched under his singlet as the woman paused in front of the long sandwich loaves, which went the furthest towards feeding a family. A clever wife, manage the house, he observed, save up to buy nice things once in a while like sea bass for dinner. Maybe this time she would buy something for the kids.

The plump boy pointed at a chocolate butter-cream slice adorned with a swirl of white cream and two jewel-bright spots of red jam. His smudged glasses slipped down his pug nose, and he pushed them up with a sweaty palm, smudging them again. "Mommy!" he called.

She was feeling the loaves for their freshness. The little emperor walked up to her and pulled at her skirt. "Mommy-mommy, I want the chocolate one."

"So much sugar not good for you." She selected a long plastic bag filled with bread and moved towards the counter. The younger boy trailed behind.

"But this one very nice. Got strawberry jam."

"No money."

The woman placed the loaf down and took out a flaking black purse, but the boy caught up with her. He jiggled about on one sweaty leg.

"Only 70 cents! Very nice!"

"Buy already you never share with your brother."

The boy gaped.

The baker interposed. "Now offer! Buy two for one dollar. Then the small one also have," he said, beckoning to the younger child. "Come, Ah Boy, you want chocolate cake?"

On milk-white, pin-stick legs, the boy ran to his mother and hid behind her skirt. Her half-moon smile grew tighter as she pointed to the loaf on the counter. "This one enough, pay up for this."

The man gave up. A good mother. Thick skin. Teach her children to listen. He checked the bag twice and keyed in the price with painful precision. No need to care about other people's children. But the plump boy continued jiggling, this time by bending both knees and heaving himself up and down in little sobs, to which his flushed cheeks quivered in time. His heavy glasses slipped helplessly to the tip of his pug nose.

"Mommy! I never eat before! I will share!"

She counted out the coins carefully into the baker's hand. He jangled them cursorily and poured them into the drawer. The boy stood by with his mouth open.

Mrs. Tan walked out of the cake shop, holding the younger boy by the hand. The fat one could take care of himself. He fought with a whimpering, iguana-like slowness for whatever he wanted. But she worried for this fragile child. Unlike his older brother, he did not whine or fuss. He was skinny, but he did not seem to want anything. With his bean-curd pale skin, his wet, raspberry mouth, and the dark circles under his eyes, he was doted upon by the aunties when they went to the market. They tried to pinch him.

She knew about the rumors: he was not well; he was dying. At dinner-time, she placed rice and steamed eggs and fried fish and cut watermelon before him, and she made sure he was chewing. Sure enough, the food disappeared with a re-assuring rapidity. That was before she found out his older brother was sneaking food off the plate after he finished his own, while the younger boy chewed the same slimy wad of rice over and over. She beat the older one for stealing from his younger.

"Mommy!"

They were passing the stationery shop now, a dank and many-shelved room which smelled sweetly of graphite and exercise books. Ah-Pui sniffed the cool air and felt on his pudgy arms the allure of side-click mechanical pencils, the erasers smelling of peaches and grapes, the country erasers imprinted with flags from across the globe.

"Mommy! I want to buy an eraser!" His brother and mother had walked on. From the stationery shop came two tanned girls shorter than Ah Pui, chattering about the Strawberry Shortcake notebooks they had bought. They were followed by their mother.

But Mrs. Tan continued walking. He began to jiggle again. "Why cannot buy?" he yelled in an aggrieved voice loud enough for the entire corridor to hear, "Why other people have I don't have?" The girls stopped to gawk at this monstrous jiggling lump, but their mother simply brushed past.

"Enough. You come here," Mrs. Tan said to the boy. Her expression was unreadable.

This time Ah Pui stood his ground, jiggling for erasers and a slice of cake. His mother did not care if the entire neighborhood heard what she had to say. She had no respect for these women who gave in to their children's demands just as they gave in to their own fancies. She had no respect for a son who ate too much.

She announced, "We have already gone for a nice lunch."

"Not enough! Not enough!"

"Then we also went to the arcade. Spent five dollars. You never shared one token with your brother."

"He don't want what! My fault meh? Everything he also don't want."

"Fine," Mrs. Tan said as she walked on towards the fruit stall. "Today when we go home I will throw away all your country erasers. You don't want to share, then you get nothing."

The boy ran up to her, screaming and dragging on her skirts amidst sweet-scented heaps of rambutans and mangosteens. "Don't throw away! I will share! I will share!" The stall keepers stared impassively from beneath naked light-bulbs. That woman again. But why bother? Not our kids anyway.

One of the men scribbled prices on cardboard plates torn from the sides of S.A. Gala apple boxes. The acrid, jaw-clenching stench of marker fluid melded promiscuously with the smells of ripening fruit. "Come-offer-come! Come-offer-come!" he bellowed, even though Mrs. Tan was the only customer. "What you want: apple, rambutan, orange! All guaranteed sweet!" He tossed down a basket to where she was selecting apples, but Ah Pui gave her no peace.

"Don't throw away!" he wailed.

She held her forefinger in his face. "If you don't want me to throw them away, show me you can behave. Hold your brother's hand and make sure he doesn't run away."

While his brother's hand was locked in his clammy fist, Ah Pui thought of the country eraser collection he had spent the whole of Primary Four building up. You flicked one eraser at another and the one on top won. That was the way Germany got him 15 others. Whenever there was a difficult match against another boy's equally famous eraser, out came Germany, and he would win. His leg was still jiggling, and his nose ran. He rubbed the mucus away with his arm angrily. The small one was tugging and pointing. What did that idiot know about anything? Germany would never lose, just like the way C was the correct answer in an MCQ test question he was clueless about. Then he lost Germany, in a freak match that saw his eraser flip over Teck Seng's, before Tanzania fell on top of his with a fatal flourish.

His brother twisted to get his hand out of his meaty grip. Where Mrs. Tan was inspecting each royal gala apple for blemishes and firm stalks, bees hovered near the dried honey longans. Ah Pui held on so tightly, the younger boy gasped and cried with pain. Always like that, he thought, stupid dumbo, you can go and die. Mommy always give you things, but you don't want. The aunty at the market know better. Everybody know you going to die. Got things must take, otherwise later don't have. Now you want to make her throw away all my country erasers. Very funny right? He crushed his brother's hand within his own, grinding the fine bird bones painfully against each other.

"Mommy! Mommy!" the younger boy screamed.

Ah Pui cuffed him across the head. "Stupid! You want to get us into trouble?" He hit him once more before he saw Mrs. Tan striding up. He let his hand go. The little boy fell to the ground, cutting his knees.

His mother was there the same instant. She picked him up and dusted his knees, while Ah Pui stood by, too afraid even to jiggle. She asked the younger boy if it hurt, but he turned from his bleeding cuts and put his face to her chest without a sound.

"What sort of brother are you?" she yelled.

Ah-Pui trembled red-faced. His flabby cheeks quivered.

"I know! Just because I want to throw away your country erasers, you take it out on him!"

"I never! He so naughty, he want to run away..."

She pointed to his brother's cuts, at which she was dabbing with a wet tissue. His kneecaps were raw and bloody. "So you're saying he fell down himself? I saw you let go!"

He did not deny it. She would throw away his country eraser collection whatever he did. To that she would add a sound beating when they got home. Now that is was for sure, he stood cowed and empty.

"Can't trust you with a simple thing!"

Mrs. Tan saw the bleeding would not stop, however brave the little boy was. She took out money from her black purse and threw it at the older boy.

"Boy, this time you listen carefully, and you better get it right. Go to the mama shop over there and buy one box of plasters. Nothing more. Then you come back. Understand?"

As Ah Pui bent to pick up the money, he nodded, so he seemed to be bowing to the floor. With the sticky notes crushed against his side, he turned to go, his spectacles slipping to the edge of his nose again. He took two steps, his slippers flapping against his scrunched-in toes.

"Only the plasters, you understand?" she yelled after him, "Don't think I don't know what you thinking. Don't you dare buy sweets with the change."

"I never say I will," he said simply.

"Don't talk back!"

He shambled on. So the country eraser collection would be down the rubbish chute tonight, and the cane would be off its hook on the telephone cupboard. Then? Balling the fist without money into his left eye, he walked on, his mouth an open gash of ragged breathing, into which he drew the dusty smell of lentils, onions, and drying jasmine when he reached the mama shop. Then she might lock him in the storeroom for the night with the hantus with their long razor nails, or throw him outside the house. Police catch you. Bangali take you away. That was when she caught him stealing his brother's food.

"Uncle, I want to buy plaster, one box," he half-sobbed in mortal fear.

Wrinkled, white-haired, glossily black-skinned and dismissive, the Indian man reached for a packet from a shelf from over his head, his crumpled linen shirt lifting over his checked sarong. He threw down the small white box on the counter, his fake rolex tinkling.

"$1.50!" His head never stopped swaying to the Tamil songs cackling from the radio.

Ah Pui passed up the money and cupped back the change in a panic. He bit back the teary hiccups convulsing his sides, making his upper lip overhang the lower so he looked like a flustered turtle. Cry for what? You think crying will change anything? The Indian man did not look at him again. Bangali take you away. Ah Pui looked directly at his yellow canines. Always showing your temper! Everything you must grumble! But the chocolate cake was cheap. Got things must take, otherwise later don't have. Care for yourself only. You think everybody got time to care for you?

Outside the mama shop, his right foot landed on the wooden ramp with a hollow explosion, but neither the Indian man nor his mother looked up. Down the corridor, he saw how she crouched like a massive mermaid, her denim skirt billowing over the bare floor. At the very edge, he glimpsed the tip of his brother's foot, encased in a red sandal, prone and unmoving. See? I know you are always so careless! If you check your work, you sure get A in this test. He shuffled along, the box of plasters held before him like a lamp. What happen? As usual you cannot control yourself, you must eat the potato chips without sharing with your brother. No dinner for you tonight! So she would throw away the country erasers tonight. His spectacles misted over. You cannot tell the difference between right and wrong. You want to eat I give you eat, you want something I buy for you. When it's time to do your homework, you don't want to do. The only thing you scared of is the cane, right?

He smudged his glasses back on his face and handed her the box. She took it.

"Why so long? I know you went to look at the toys, right? Give me the change."

Ah Pui closed his eyes. She stopped dabbing at his brother's knee and tore open the box. After detaching a plaster from the strip, she re-considered the change in her pocket.

"Stop sleeping!" she barked, "You don't care what happen to your brother?"

He opened his eyes and saw his brother sprawled against their mother with his flimsy legs held before him. His wounds gaped like mouths. He was dying.

This time she handed him only a two dollar note. "Go back to the mama shop and get some sweets for your brother. Hurry up, we're going to the bus stop soon."

When they got home, she would throw away his country eraser collection. But Germany always lose. Now he always lose. There was a time when his younger brother ate as much as anyone: bowls of fish porridge stringed through with mushy spinach, hot oats with black sauce and egg. Only that their mother had to follow him with the bowl to the hall, outside the gate, downstairs to the car-park where the school buses honked and picked up their noon-load of uniformed and shrieking children. Between mouthfuls, he pointed, ran, played on the swings. One day there was no bowl of lunch for him. Got things must take, otherwise later don't have. There were no lollies, no chips, no snacks, but he rolled on the rug and laughed at the TV. By 6:00 he was quiet in his room, listening pensively to the sizzle of fish slipped into oil. Ah Pui ate fearfully and copiously from steaming mounds of rice, from dishes piled high with fried eggplant in blackbean sauce and tengiri with chillies and onions. His father said something. "I am disciplining him!" his mother screamed, "He'll get nothing until he learns to eat properly." From then on, Ah Pui was always hungry. The second night, his brother sat at the table, chewing but not swallowing, allowing him to finish the food when their mother was not looking. He shivered in the recesses of his belly-fat. The Indian man was no longer anything other than an Indian man. Two chupa-chups. 120. He gripped the cola-flavored lollies, suddenly hungry, but they were for his brother who was dying.

He looked down the corridor and saw his brother was limping along with the help of his mother. They had started for the bus stop by the shops without him.

"Hurry up! Why are you so slow?" she yelled. 178 rounded the corner. Ah Pui started to run, the red lollipops held before him like flowers, his gut fats jiggling of their own accord. "Quick! Going home already!"

He ran up with the chupa-chups and she handed him his EZ link card.

"Don't eat now, ah," she warned, forgetting they were all meant for his younger brother. "Go home then eat, share with your brother."

They boarded the bus in a scramble with a burly tattooed man and an old lady flourishing a lace handkerchief pungent with eucalyptus oil. She shoved him aside. "Aiyoh," he sighed, unable to push back.

"Hold your brother!" his mother called from behind the man. "Don't make him fall down!"

But Ah Pui was already holding his younger brother tight. The bus began to move. He passed the lollies to the younger boy, who started to unwrap them.

"Don't eat now!" Ah Pui cried, "Go home then eat!"

The lights turned red and the bus hurled to a stop. His brother fell face-down, thin, bendable as drink straws. The chupa-chup hit the back of his throat, the lollie-stick lanced through his cheek.

His mother pushed through. "I told you! I told you!" she shrieked.

When the news broke the next day, no one was surprised.