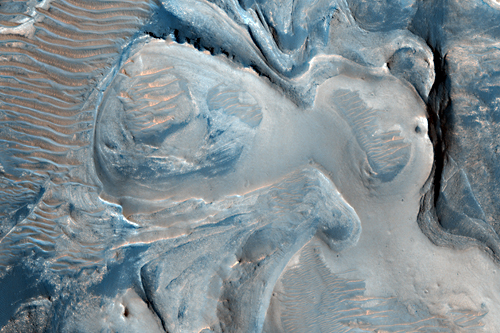

Image: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

In July I had to go to this baseball death camp. The first day I stood outside the clubhouse in the 100 degrees plus the humidity, and my purple jersey stuck to my skin like saran wrap, and all I could think about was how I was not a team player. My new baseball mitt was rigor mortis stiff. I was really bothered the pants didn't have pockets. The chain link fences had just been replaced that year and glinted in the sunlight. I tried touching one, and it was like gripping a light bulb. Everything smelled like brown dirt and fertilizer.

I was supposed to go to dugout number three, except I didn't know which one it was. They had been handing out a paper with the map on it, but I forgot to pick one up, and I missed all the other purple jersey kids because I had to go to the bathroom. I walked in the direction of the closest dugout. A 17-looking guy with bleached hair and a blue lanyard indicating he was a counselor walked past me.

"Is that dugout number three?" I asked. He made a sound like he was scraping his throat with sandpaper and hocked a big loogie to my left and kept walking. It's not even ten o'clock yet, I thought.

There were no purple jersey kids at the first dugout. I started towards the other two, thinking I saw something purple at the furthest dugout. I had to go downhill, so I was walking like a jackass. I wasn't born this way, I kept trying to tell myself.

The way the camp worked was like cramming a four-month baseball season into four weeks. We were sorted into teams—there were five in all—and we were supposed to practice and play with them for the whole month. My team was called "The Lookouts." My jersey number was 67.

The dugout was this wooden shack painted white with a big red "three" on the side. A guy with a beer belly just screaming "head coach" was heaving a cooler of water out of the dugout, and he eased it onto a plastic chair that creaked like it was going to break. He paused a moment to hike up his khaki shorts and scratch his crotch, and then he looked at me and asked, "Who are you?"

"Is this dugout number three?" I asked.

He gave me this look like, Oh, man, kid.

"You're late," he said. "Grab a seat."

I walked inside the dugout, and it was like a go-cart sauntering into a monster truck rally. Every sports movie I had ever seen starred a team full of geeks, losers, and rejects, usually captained by an equally loser coach who was emotionally sensitive and had something to prove to his father, and they would suck until some good player joined the team and whipped them all into shape. I had hoped I would be placed on this team so, between gulps from our asthma inhalers, I could have a rousing discussion with my teammates about the reproductive techniques of the spider wasp. However, I was on the other team: the team of 12-year-olds with six packs who bragged about how much they could bench. The team that spent most of the movie kicking my team's ass.

I took a seat next to a pubescent science project with hair growing out of his knuckles. He turned to me and licked his lips. I must have really pissed on some Indian burial ground for this, I thought.

"This can be the one favor you do me in your whole life," my dad had said.

We were both out of breath. I was sitting on the couch, and he was kneeling and holding my feet with his hands. All I wanted was to drop dead. He had had to throw my half-brother, Pete, out of the house to break us up. The ceramic ashtray I had made in art class had gotten knocked off the coffee table at some point and was broken on the floor.

"It's one stinkin' month. It won't kill you."

It was two days before camp started. He asked why Pete and I had been fighting. I told him I had gotten mad at him because I didn't want to go to baseball camp. He asked me why I didn't want to go. I said I thought the kids would make fun of me.

"You haven't even met them yet!" he said.

I said I sucked at baseball.

"You'll get better. What d'you think camp's for?" he said.

I didn't see why I was making such a big deal about it myself. Mom and Dad were trying to coordinate their vacation days so at least one of them could be around most of the time, but it still only added up to most of August. It seemed like things were getting worse with Pete, and the last thing they wanted was for us to be alone together in the house all day.

"But you've always loved baseball," was mom's argument. I had played on a Little League team the year before. Here's what that was like: kids learned new words just to make fun of me. I didn't care because I didn't think I would ever have to play again.

Dad's complaint was no one was ever on his side. Mom was always siding with Pete, Pete was always siding with her, and while I should be helping him out, it looked like I just wanted to tear the whole house down. Here he was busting his ass trying to keep me out of trouble, mom from going nuts, and my half-brother from wrecking his life, but Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, it didn't look like anyone was going to do him any favors.

"Let's think about us for second," he said. The four of us were sitting around in the living room. Mom was pissed because it looked like dad had thrown Pete out of the house again. Pete was looking at me like the whole thing was my fault. There was so much staying calm going on, it could have popped a blood vessel.

"No, let's think about you," Mom said.

"Okay, let's think about me," Dad said.

Every morning, while he stuffed me in the back of his car, Dad reminded me I was doing this for a cause. "It's for your brother," he said. It was also for Mom and it was also for him. He was going to fix things, and this was how I was going to help. He put it in terms of doing our jobs. Mom's job was to put up with her job. Pete's job was to find a job. My job was to go to baseball camp. And his job was to keep it all together. When I was signed up and had my jersey and everything, he bent down and gave me a kiss on the forehead and whispered, "Thank you," and turned to leave me standing there in the sun.

The coach started giving a speech. I looked down the bench to see if there was anyone who looked like he couldn't bite off my head. There was one light-haired kid who looked about the same size as me, but then I heard him crack his knuckles from halfway across the dugout.

When the coach was finished with his speech, he clapped his hands together and said, "Okay, boys. First thing is we're going to do some suicides."

Great, I thought. Though when I thought about suicides, I thought of taking a sans-parachute stroll out of a 747, or knocking back a glass of bleach, and I got the feeling this was going to be different.

What it actually meant was we had to run our butts up and down the field for like an hour. When it was all over, I felt like puking, but then the coach told us to get our gloves, because we were going to practice catching. In addition to the coach, there was another lanyard-wearing counselor like the one I had seen before. This one had a buzz cut, and his nose seemed to lean a little too far to the right. His name was Monty. He looked like the guy in a World War II movie who's an asshole but he gets shot halfway through and you feel bad about it anyway. We had an odd number of people on the team, so I ended up playing catch with him. I asked if he could just lob them nice and easy, and instead he sneezed on the ball and kept launching them at my face.

The coach clapped his hands again and said it was time for lunch. He never said anything without clapping his hands first. We all hiked back up to the clubhouse, where we had an assigned table where the team was supposed to eat together.

They had a couple crates full of ham and cheese sandwiches in shrink-wrap, bananas, and bottles of either iced tea or water. I was behind a curly-haired kid who was on the blue jersey team. He looked at the guy passing out sandwiches and said, "I'm not supposed to eat ham."

"Then get two bananas," the guy said.

The kid rolled his eyes and went to the banana crate. I took a sandwich. When I got to the banana crate, I felt sorry for the kid who couldn't eat ham. Most of the bananas were only kind of yellow, as in, they were mostly brown. I hovered over them, trying to pick out one at least 60-percent normal looking when Monty came over and said, "You gonna take one or just stare at them all day?"

I didn't want to do either, but I grabbed one and sat down at the table. The kid next to me was already halfway through his sandwich.

"So, what's your name?" I asked.

"Shut up, shitface," he said.

Great, I thought. Shitface. Some other kid snickered. I ate my sandwich slowly so I wouldn't have to look up. When I was done, I considered the banana but decided the brown spot was too big.

"You gonna eat that?" the kid who called me shitface asked.

"Have at it," I said, pushing it towards him.

I drank the rest of my water quickly. The light-haired kid from before was sitting across from us and started talking. His name was Dan. "Not 'Danny,' just 'Dan,'" I remembered him correcting the coach. He was really interested in what everybody's dad did.

"What's your dad do?" Dan asked the shitface kid.

"Your mom," he replied.

"Wiseass," Dan said. He turned to me. "What's your dad do?"

"He's the mailman," I said. Dan nodded his head. There was a pause, and then Dan started talking again to no one in particular.

"I talked to this one kid, and his dad's a fucking dentist. Can you believe it?"

When lunch was over, we went back to drilling. The shitface kid's name was Robby. His jaw seemed to hang low in his mouth. He was a dick to me, but he was also a dick to everybody.

"You sure got issues, kid," the coach told him.

"Yeah, I do," Robby replied.

What had happened was Robby had told another kid to fuck off for what was apparently the last time, and things were already getting ugly when the coach broke them up. I was trying to catch grounders from Monty. He gave the coach this expectant look, like he'd been waiting to be given the okay to break some kid's bones, but the coach waved him off. The grounders started coming a little harder.

When it was finally five o'clock, I limped back to the clubhouse where my dad was waiting for me. I limped because some kid Ty Cobb'd me in the thigh when we were running a scrimmage. That's what the coach called it. "No Ty Cobbing each other," he said. I had dirt stains on the inside of my jersey. We sort of nodded to each other wordlessly, like we were about to go pull a jewel heist. We stopped and got some fast food on the way back.

It looked like Pete wasn't going back to school. The last two months that year dad practically had to beat him up every morning to get him out of bed, and even once he got there, he didn't go to class.

"You're in some deep shit, bud." That was the last thing Dad had to say to him before the summer let out. Mom's opinion was they needed to try another therapist.

"How's that going to fix anything?" he asked.

"Maybe there's something they missed," Mom said. "Maybe he needs someone new to talk to."

"He's been seeing someone new every couple of months," he said.

The way Dad put it was he could take a breather whenever I was in school, because I studied enough that it kept me busy. The worst trouble I had gotten in was the year before, for drawing a picture of a cruise missile in my notebook. It would have been okay, if it hadn't been heading straight for a rectangle which I had labeled "school." It was when I got cooped up in the summer with my half-brother that Dad said he couldn't take it. Pete had taken to hanging around the house all the time. He didn't go over to his friends' houses anymore. His band had broken up and reformed without him. He didn't want to get a job anywhere. Throw me in the mix, and our house was on a hair trigger.

Mom was sitting on the couch watching TV when we got home. Dad took the bags of food into the kitchen and grabbed a beer. She was wearing his Phillies T-shirt.

"Come here and sit for a moment, sweetheart," she said. I flopped on the couch and felt my butt press up against the spring. She stroked the back of my neck with her fingers. I had some fleeting idea if she could understand the way I felt, then everything would get better.

"Did you have any fun today?" she asked.

"Not really," I said, and I felt bad about saying it. There was a moment where she just let her palm rest on my shoulder. I was waiting for her to say I didn't have to go, and I would feel bad and say yeah, I did, but then she said, "It'll get better. Besides, it's only a month." Which made me feel even worse.

Dad came out and told me to come eat. Mom and Pete had made sandwiches earlier. I went into the kitchen, and we sat at the table eating our hamburgers. He guzzled down his beer pretty quickly and scratched his face. He had the kind of five o'clock shadow that grows back by noon.

"You know something?" he said. "You're a really great kid. Best in the world."

I dug a French fry into a puddle of ketchup.

"I don't think I can go for a month like this," I said.

"Yeah, you can," he said, like that settled it.

"No, I really can't."

"Jesus H. Christ, whatever happened to just trying something?" he said. He looked ready to turn the table over. I was about to tell him I would sooner use a baseball bat to bludgeon myself to death when he said, "I don't want to hear it. Just shut up and eat."

He slumped his head into his hand. "Just shut up and eat your goddamn food."

When we were done eating, he crumbled everything up into one big ball of paper and tossed it in the trashcan. He stopped me as I started up the stairs.

"If I hear so much as the floor creaking the wrong way, you both are sleeping outside tonight. You hear me?" he said.

"I'm just gonna go read a book," I said.

"Then read it in the kitchen or something," he said. "Just don't provoke him."

Part of the problem was Pete and I still had to share a room. I walked in, and he was sitting on his bed, reading a car magazine, even though he'd failed his driving test. He'd been down to the DMV at least three times, and every time he had come home and broken something, and last time it had been my glass replica of a mosquito trapped in amber.

"Sup, fag?" he asked.

"Nothing, dick," I said.

I sat down on the side of my bed and looked at the floor. I was dirty, but I didn't feel like taking a shower. My hands had bloody skid-marks on them from tripping over someone in the dugout. I kept my books and my movies on the same shelf next to my bed. I checked them every day, because Pete was always stealing my movies, and he usually ended up losing or breaking them. He would yank them out of the VCR all wrong and screw the tape up.

"Where's The Offering?" I asked.

"I didn't touch The Offering," he said.

"This case is empty. It was full the other day," I said.

"I told you I don't know what happened to it," he said.

"It didn't get out of its box and walk away," I said.

He ignored me and went back to reading, and I wanted to run at him and beat his face in, but instead I started looking around the room. I ducked under the beds and opened all the drawers, checking all the stupidest places.

"What are you doing?" Pete finally asked.

"I'm looking for my movie," I said.

"Well, stop, cause you're not gonna find it," he said.

"Then tell me where it is," I said.

"I said I don't know where it is," he said.

"Yeah, you do," I said. I added, "You retarded dipshit."

It was the same satisfaction as picking at a big, chunky scab. As he got up from his bed and put me in a full nelson, I tried to think of why it seemed so natural for us, why this was the path of least resistance. I tackled him in his midsection and knocked him into the bureau. He threw me to the floor. I heard stomping on the stairs.

"Now you've done it, asshole," I said.

Dad came in and grabbed us both by our necks and flung us onto our beds.

"Just what makes you do this?" he asked.

He yelled at us for about ten minutes, mostly about things we knew, like you know your mother and I are trying to work this out and you know there's not enough space in this house and you know how much trouble you're going to be in if in five minutes one of you doesn't get his ass downstairs. He slammed the door on the way out. Pete curled up on his bed and pulled out another magazine. I forgot about my movie and checked up on my ant farm. I decided I needed to hunt for more ants at the ballpark if I got the chance. After four minutes, Pete was the one who got up and headed for the door. "Freak," I heard him say. I didn't hear whom he was talking about. I just nodded my head, watching the ants in their tunnels as they burrowed deeper and deeper into the dirt.

"I hear he got it from the mafia," Dan said. "For being a snitch."

"No way. I heard him say it was from football," another kid said.

"Well, he told me he got hit with a baseball bat."

"You asked him?"

They were talking about Monty's nose. We were on a bus, driving over to Veteran's Stadium in Philly. It was this big special thing. The whole camp was going to get to go and practice on the field and see the Phillies' locker room. We were told we might also get to meet one of the Phillies, and there was all this hubbub about who everyone wanted to meet. It wouldn't have made a difference to me if we were meeting Babe Ruth.

I was sitting next to Robby, which wasn't ideal. He seemed to agree. His butt took up most of the seat. The only thing he said to me the whole trip was, "Stop breathing so weird."

Next to me, Robby was kind of the worst player on the team. The thing is, I was so bad, I could be ignored, but Robby was kind of decent, so he had something to lose. That, and it didn't help he never said anything other than a command or a rhetorical question. It didn't matter anyway; our team destroyed everything in its path. I only got made fun of for sucking, which is different from being blamed for it. We won the first two games of the week by stupidly high margins, like 16—3, or 12—1. Some genius came up with the slogan, "Look Out for the Lookouts!"

When I told that to dad, he got really excited. "See, I told you you'd like it," he said.

"No, you listen to me," Dan said. He was talking to somebody about three seats up from him.

The first time I had been to the Vet for a game was when I was maybe six or seven. We got some decent seats in the 300 level, and Dad said it was the first time he hadn't sat in the 700s. He pointed out all the bases and tried explaining how the game worked, but I kept getting distracted by the jumbotron. Mom bought me some Crackerjacks, because that was how it was in the song. I hurt my tooth on a peanut.

When I had to go to the bathroom, I went with Dad and Pete. We had to wait like five minutes for the urinals to open up. I ended up taking the longest to pee, so they were waiting for me. When I came out of the bathroom, Pete was standing against the wall with his hands in his pockets and Dad was talking to another man. Both of their faces looked flushed, and they were talking quickly.

I turned to Pete and asked, "What's going on?" Pete sort of shifted his shoulders around.

"Your dad's talking to my dad," he said. I didn't understand what he meant at the time. I thought we both had the same dad. We went back to our seats and Mom smiled and said, "You missed the triple of the century. No, the millennium."

Mom kept cheering, but Dad was sort of quiet for the rest of the game.

Pete's real dad never visited, and that was the only time I ever saw him. Pete only talked about him once, two years ago. I was home sick with strep throat, and he was home because the high school didn't have to go back until the second week of January, and we watched this movie on TV. It was a really dopey father-son sort of thing, and I could tell we both hated watching it, but we sat through it the whole way. Later I asked him if he ever saw his dad.

"Not really," he said. "He's crazy anyway. That's why Mom left." He started picking at one of his fingernails. "That's why I'm crazy. Because I caught it from him."

"Jeff's pretty crazy, too," I said. I only called my dad "Jeff" when I was talking to Pete, because that's what he called him.

"Jeff's okay," Pete said. "You're okay."

We pulled off the freeway and into the parking lot, which stretched like a dull grey desert around the stadium. The sky was drab and smoggy: "Philadelphia-colored" was what mom called it. Everything was concrete for miles in every direction, and the horizon was dotted with oil tanks and the lumbering high-rises of the city skyline. The stadium itself looked like a colorless stone salad bowl. The coaches herded us off the bus, and we grouped ourselves into teams. Some guys in red Phillies jackets came and greeted us, and we all followed them inside.

They took us down onto the field. There was blue tarp laid out in some places, and an old man was pushing a hand truck to put down the base lines. The grass felt more Astro-turfy than I thought it would. The red jacket guys told us none of the Phillies team members were around, but maybe they'd show up later. They started giving us some spiel on the place's history.

"Bo-ring," some kid yawned.

We split off into our teams and did drills like we did every morning. It felt stupid, and I was tired, so I sat down for a bit. Monty came over and said, "Get up."

"I don't want to," I said. All of a sudden I was on my feet and wasn't sure how I'd gotten there. Monty was grabbing me by the back of my jersey.

"Get goin'," he said. I started running.

Afterwards, we got to see the locker room, as promised. It was just a big room full of jerseys, and it smelled like lemon air freshener. Everyone else kind of ooh'ed and ahh'ed. I even heard one kid go, "This is so cool," and it made me want to knock him over. I hated feeling like I was missing something. Like the world was an inside joke I wasn't in on.

When that was over with, we had some free time to walk around the stadium.

"We're gonna use a buddy system," the head coach said. "So you don't get lost."

Great, I thought. The buddy system. My buddy ended up being Dan.

"How'd I get stuck with this kid?" he asked. He was asking me.

I expected Dan to go off with someone else, but he ended up just lounging around while everyone split away. Finally, he looked at me and said, "I'm going this way."

"Fantastic," I said.

"Wiseass," he said.

I followed about ten feet behind him. I had been to the stadium a couple times already, so everything seemed familiar: the cold cement walls, billboards advertising beer, shops full of hats and jerseys and stuffed Philly Phanatics. Dad was always complaining about how the stadium looked like a piss-bowl with its brown and yellow seats. The hot dogs tasted watery, but I was hungry and wished a vendor were open. Dan was looking around like the Phillies could pop out any second.

"This place is huge," he said. It sounded like he was talking to himself, so I didn't answer.

"Well, aren't you gonna say something?" he asked.

I gave him my best "Are you serious?" look. "Haven't you ever been here before?" I asked. He shook his head.

"My grandmom doesn't like to go to games," he said.

I scrunched my eyebrows together because I didn't know what he meant. I felt this sinking in my stomach like it was the physical version of the phrase "Things never work out the way you want them to." We kept walking for a bit without saying anything, and I saw Robby standing alone, leaning against a railing. I wanted to keep walking, but Dan had to go and say, "What're you doin'?"

"What's it to you, fuckface?" he said back.

I thought we were going to leave it at that, but then he started walking next to us.

"Who're you with?" Dan asked.

"I'm not with anybody," Robby said.

"Don't be a fuckin' liar," Dan said. "Everybody's with someone."

"Who gives a shit?" Robby said, but then he added, "I was with Monty. I ditched him."

"Monty'll kill you, you know," I said. I tried to sound experienced, because I was.

"I don't care," Robby said, and we kept walking. I wanted to ask him what he was doing following us if he wanted to be by himself, but asking Robby for a reason was the sort of thing that got you beat up, so I just kept staring at the walls. There wasn't much to see inside the stadium. After circling the concourse, even Dan started to get bored and complained about being tired. He made us stop at a bathroom, and I was stuck outside with Robby.

"So what's your problem?" Robby asked. The way he said it made me think, I'm not like you. I just pretended like I hadn't heard. As if to make his point he added, "You don't say anything ever."

And what am I supposed to say to that, I thought. Because I don't want to talk to anybody; because I've got nothing to say; because nobody likes it when I say things; because I don't like it when I say things. Maybe I had answers, but I didn't want to tell them to him, and I didn't want to tell them to anybody. Robby looked like he was getting mad, but I didn't have time to answer because Dan ran back out of the bathroom.

"You guys, Monty's in there," he said. "We gotta get out of here."

I felt a buzz like we were playing jailbreak, but I couldn't think of why this was my problem.

"We gotta go now," Dan said, as Monty pushed him out of the way and came up to Robby.

"You. Let's go," he said. "Big trouble." Monty's small black eyes were fixed into Robby's. The phrase "Like a doll's eyes" popped into my head.

"Screw you," Robby said.

You idiot, I wanted to say. At the same time I wanted to see what would happen. Dan was backed up against the wall, like he was next or something. Monty let his shoulders droop for a moment and stood there. Then he snatched Robby by his collar and hoisted him up. I could hear the fabric ripping somewhere.

"Don't make me drag you, pal," he said. Then I couldn't tell whether it was from Robby struggling or whether Monty just threw him, but Robby fell backwards and landed with a meaty thud on the cement floor. Monty reached down and started pulling Robby by the neck.

"What're you two lookin' at?" he asked.

"Nothing," I said.

"Nothing," Dan said.

Monty nodded his head and kept forcing Robby back down the concourse. Dan looked like he had just caught the game ball.

"Holy shit!" he said.

Didn't he know the consequences? I thought. What did he think would happen? When they were out of sight, we started in the same direction until we came to the meet-up point, where Robby was sitting on a bench and Monty was talking to the coach, who kept fiddling with the whistle around his neck like he was going to break it.

"Maybe we should say something?" Dan said.

"Like what?" I asked. He didn't reply. We just stood there watching the coach yell at Robby until all the kids filtered back in and it was time to go home.

Dad drove into the parking lot ten minutes later than usual in our neighbor's white sedan. I recognized it by the clump of tree-shaped air fresheners hanging off the rear-view mirror. I should have known something was up and to not screw around, but I still did this thing: ever since I limped back to his car the first day, I had taken to staggering up to him after camp like I had just crawled away from a gang fight. He wasn't in the mood today.

"Hurry up and get in the goddamn car," he said.

This can't be my fault, I thought, and I tried to think of what I'd done.

We weren't driving faster than usual, but I could tell we were hurrying. I didn't want to ask the question, but I felt like someone had thrust a script under my nose, and I had to say it.

"So, where's our car?" I asked.

"Pete has it," Dad replied. We didn't say another word to each other until we got home.

He told me to get inside while he returned the car. I went in and Mom was standing around, and she came over to me and asked if I was okay.

"Pete can't drive," I said, like I could prove them wrong. "He doesn't have his license."

"We have the police looking for him now," Mom said.

Dad came back in and asked, "Are you hungry?" Without waiting for an answer, he went right into the kitchen and started boiling some hot dogs. Mom kept pacing around the living room, readjusting lampshades and stacking and unstacking coasters, all the while telling me not to worry. I sat on the couch and rubbed my ankles together. Dad told us the food was ready. We were out of hot dog buns, so we just ate them using slices of white bread. Mom and Dad didn't look at each other the whole time, and I did nothing but look at them until it felt so bad I had to just look at my feet.

I couldn't stand it when Mom and Dad didn't talk to each other. I wanted them to argue or yell about whose fault this was, but when they didn't say anything, it made me feel like it was my fault. After dinner they started watching the news, and I asked if I could watch a movie, and mom said, "Sure." I went up to my room and didn't want to come back down.

I could already see it in my face whenever I looked into the mirror. One day, I was going to look just like my father. I was a scrawny kid, but I was going to fill in someday, and people would say it was uncanny, the resemblance. They said it already. When Pete and I were together, like brushing our teeth or something, I tried to find our mother in both of us, to find something linking us together. I wanted to find what was always there, what had been done to us, what had been flowing through our bloodstreams since before we had the chance to know.

I didn't feel like watching a movie anymore. Instead, I grabbed a book about reptiles and went back downstairs and started reading about Gila monsters. After a while, Mom or Dad started flipping through the channels.

At 10:30 the phone rang, and by midnight Pete was standing at the door with a police officer behind him. They had caught him going south down I-95. He had stopped at a rest station. Apparently he hadn't given the officers any grief, either, so he was only in trouble for driving without a license. They gave us the ticket and told us we'd get the court date later.

When the officer left and the car was parked back on the sidewalk, it was just the four of us in the living room again. Mom had started crying. I didn't register a word Dad was saying. I was sitting on the floor, my book still open, and I could have left the room at any time, and I wanted to leave, but I felt I was the only one Pete could see at the moment. Because I was the kid who hadn't run away.

Dad was tired of talking, and it was Mom's turn to have her say, so he came over to me and said, quietly, "Hit the sack." I didn't even bother to brush my teeth or take off my dirty underwear. I sat lying awake in bed, getting sticky with sweat, until I heard the door open and saw Pete climb into his own bed.

I remembered something Dad had told me once. People don't actually think about you all the time. He said it to comfort me, because I was being a kid and believed no one ever forgot about the bad things I did, like throwing fits and getting into fights with Pete. I thought about that, and I thought about Pete taking the keys to the car and driving down the highway, and I could imagine every bad thing I'd ever done to him playing through his head like on a tape. Thinking about it made me do something I really didn't want to do, which was cry. It made me want to smother myself. I pressed the pillow up against my eyeballs to try and stop the tears. Then Pete did something he'd only done once before. It was the night after the cruise missile fiasco. I was worried because I thought they were going to suspend me from school. I was crying in bed, and Pete came over and lay down next to me and started patting my head. He kept patting my head, and it made me cry harder and harder.

What had scared me then was the thought I was really just like him; that we were brothers through and through.

"What's going to happen?" I had asked.

"It's okay. It's okay," he said.

What I wanted to do was to tell him we didn't have to hate each other, and that I never hated him. I wanted to tell him we didn't always have to be fighting and breaking each other's things, and that it'd be okay if he wanted to borrow my movies as long as he asked first. We could watch them together. I wanted to tell him even though I wasn't his full-brother and Dad wasn't his father, we could still be friends. We could help each other get over our problems. We could be just like anyone else.

Instead, here's what happened: I fell asleep and woke up the next morning and went to baseball camp. I continued to suck, and the kids continued to hate me, and Robby continued to hate everybody, and the Lookouts kept winning game after game. Eventually Pete came out with his reasons: he just wanted to go for a drive; he didn't think it was fair he couldn't. I repeated them to myself until I was convinced they were true. Because what was the alternative?

When camp was over, everybody got a little gold-colored trophy with the player's team and number embossed on the plaque, so mine read: "The Lookouts, Number 67." I did my job. I did what I was supposed to do. But I didn't do it for my team, or my family, and I didn't do it for Pete. I did it because it was the only way I could avoid hating myself. I did it because I was learning the difference between what had been done to me and what I had done on my own. I did it for the same reason any of us do anything we don't understand: because we want to see what we're really made of; we want to see just how far we can pick at the scab before it bleeds; we want to see what we can create; we want to see what we can destroy.