| Jul/Aug 2014 • Travel |

| Jul/Aug 2014 • Travel |

Image credit: Darryl Leja, NHGRI, Digital Media Database, www.genome.gov

War is everywhere, marauding, rolling, random, perpetual. I forget who said that. Perhaps it was Bob Marley. At any rate, we live in a world of war, which, if it isn't occurring outside right now, is on its way here and will arrive shortly. You can set your watch by it.

The air route from Kuwait City to Beirut crosses several regions where war is going on, or has just passed, or is coming soon. The airplane, in this case a Kuwait Airways Airbus 310, skirts the Zionist entity to the west, then veers east—just in case someone fires off one of those American-funded smart missiles, but also because the folks back home might raise a clamor if the Airbus got too close. (The folks back home are the real enemy in this part of the world.) We follow a narrow jinking route just inside Syrian airspace, where, thousands of feet below, a Russian-made tank is flattening a residential block.

"Beirut International Airport" carries a lot of baggage. Hijackings, hostages, and Hezbollah run through my mind as I peer down through threadbare stratus. This was the place where Israeli commandos destroyed 13 civilian aircraft (1968); where "suicide-bombing" first became a journalistic buzzword, 281 American marines and 58 French paratroopers perishing when two trucks carrying 5,000 kilos of TNT were driven into their barracks (1983); where you could hear a pin drop during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990); where Israel dumped most of its shell-casings during the 2006 war; where Terry Waite, John McCarthy, Terry Anderson, Thomas Sutherland, and Brian Keenan landed before being kept hostage, largely in solitary confinement in Waite's case, for over four years by the Party of God. I felt I was entering what the Arabs call "the gates of hell," and what the English, with typical understatement and much less enthusiasm, call "a hornet's nest."

Whisked off the Arrival's floor by a morose, shirt-sleeved cove who seemed not to have shaved for several days—seizing my bag, he'd said he could find me a taxi—I noticed that the airport had changed its name and was now Beirut-Rafic Hariri International Airport. Rafic Hariri was a much-loved former premier who contrived the reconstruction of Beirut, cleaned up the streets, and donated millions to victims of the Civil War, but who was blown up in 2005 for his trouble. Nobody knew who'd done it, though everybody knew who hadn't. This country hurt even its own. I had an image of a dog whirling in the dust, snapping at its own tail. That was what happened in places where everybody was always right, no matter how divergent or contradictory their views.

If they could do that to one of their own, what could they do to me? Brian Keenan, also a teacher, had been snatched from the street just after leaving his home, not so far from where I was going. He had done nothing, other than look too British. (Keenan was Irish, but that didn't matter. On such small errata are empires built, contested and dissolved.) Britain was in bed with America, which was in bed with Israel, etc. So when a jittery man with evasive eyes drove me off at speed in a People Carrier, I had my heart in my mouth. The man asked, with rather too much unctuousness for my taste, if I minded him picking up his brother before we plunged into the darkness of Beirut in search of my hotel. Merciful heavens, I thought, will the brother leap into the back with me, zipcuff my wrists, blindfold me, and prod my belly with a Kalashnikov till we reach some cellar in the darkest recesses? I felt I was taking a hell of a chance when, reaching instinctively for the cant words of the region, I said, "No problem."

There wasn't a problem, disappointingly, though the drive seemed interminable and unnecessary, pursuing an unlikely up-and-down route between crumbling masonry and the odd, bullet-holed hoarding of another era. The brothers chatted in the front while I viewed the new tower blocks, glimpsing blue sea to the left and rocky mountains to the right. The famous cedars must have been a long way out of town, but there were cypresses dotting the rubble of the building-sites like careful brush-strokes, and soon pretty ateliers and shuttered villas sprang up all over the hillsides. The hotel was up a side street a few hundred yards down from the posh Clemenceau district and the hip Skin Clinic I was bound for. I wasn't planning to interview Hassan Nasrallah or confront the different religious groupings, Armenian, Maronite, Eastern Orthodox, and Assyrian Christian, and Shi'a and Sunni Muslim, over a hubble-bubble. Nor was I really looking for action in a four-by-four stone cell. I was here to get a carcinogenic spot cut out of my temple.

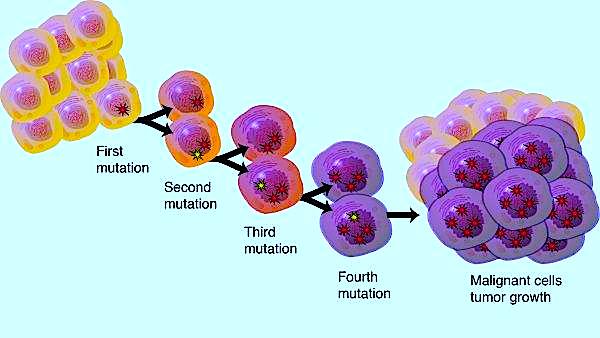

Skin cancer and war are alike in some ways. Both are potentially fatal, and both can induce panic and paupery, but the similarities soon end when you consider that the former is curable. In fact, the comparison may even seem cheap and offensive, alongside the columns of misery, uprootings, desuetude, physical torment, and long-winded death the latter has brought over the centuries. I say "seem" because "is" has recently undergone a sustained beating at the hands of some pretty skilled interrogators. We are too used now to the simulacra of video games, war games, splatter and smear movies, simulations and dissimulations, and French high theory to find reality all that unbearable. Estrangement and insulation from the smells, tastes, and feel of things bring spectatorial relaxation and the pleasures of play. Brecht's alienation effect is inverted—the distantiated playgoer is not a critical observer; he enjoys the action as action. Our new world is immersive, intense, but also abstract and dreamlike. Reality has become unreal. I remember pilots overflying Iraq during the first Gulf war, their excited viewing of the computer screens in the noses of their jets, as they released a bomb and watched it drop: Hey man, a hit! But this insulation was not only theirs; the victims seemed to experience a highly stylized, highly theatrical high all of their own. The thrill informed the kill; it was the fun that counted. Wow. Nothing like blasting another being into a thousand messy pieces over a video feed, or cradling one's dying child in one's arms in front of a camera.

The taxi pulled up at a seedy-looking joint with a succession of startled porters on hand to open doors. The room wasn't bad, and I enjoyed a beer—the first in months—before heading out to look at the city. The evening was chilly, almost bracing on the Corniche, with moisture in the air that soon turned into drops of fat, cold rain. I walked up to Clemenceau, intrigued as much by the Beiruti's apparent fondness for pro-Semitic French statesmen over the Middle East's customary reverence for 16th century Muslim divines as by the need to identify my destination. The street I was looking for was called Maamari. (Mousa Maamari, it turned out, was a Lebanese-Syrian patriot, famous for building a literal castle in the air in order win over his glacial, upper-class beloved.) It lay at the end of a zigzag between ancient black cypresses and green-tinted plate-glass cubes housing coffee shops and bookstores. I would return early the next day for an appointment with the man whose name bore an unsettling resemblance to the name of the thing he would extirpate from my face.

On the Corniche, I couldn't see the Lebanon Mountains, but I could see the snow on the summits, white frosting for the world's choppy grey cake. Flags streamed above the Port Authority, and gulls got tugged sideways. I aimed my camera at the scruffy black kids begging on the intersections. Handy place for bumming a meal, as the traffic jams were nearly immobile. The rain grew stronger, suddenly rebounding off the cars like tracer fire, then as suddenly died down to drizzle. On the hotel street, lights burned orange over a pizza oven, and a fat old man in a medieval turban sat above his wares in a grocery, lit like a shrine, the bottles of liquor behind him suggestive of votives. I was struck by the young African women—Liberian, the skin doctor opined later—emerging from the blocks of flats, sheathed in leatherette and lipstick, heading for trysts on the Corniche.

Skin cancer is a post-industrial late-capitalist phenomenon, like obesity, sex addiction, and bipolar disorder. Not strictly-speaking a racial marker, it is, nevertheless, most often found amongst fair-skinned northerners. Privileged pain photo-bombs the commoner sorts of suffering, but like everything rushed too readily into the limelight, trampling the amputees, shell-shocked, paraplegic and malnourished underfoot, it soon becomes ludic. Orange tans, strawberry fretworks of liquid nitrogen freezings, droopy straw hats and glistening, sun-blocked faces. I felt I was at one with Valentino Garavani.

The doctor worked busily, chattily, efficiently slicing through the tumor and extracting it for lab tests, which proved negative. "All out," he said, with a jaunty kind of relish, leaving me to the mercy of his assistant while he rushed off to fondle a pair of breasts in the next cubicle. The assistant staunched the wound with wads of surgical bandage, which she built up on one side of my head and face and wound round my skull till it resembled a footballer's head-guard, and then turned me out into shafts of brilliant sunshine. The air had been vacuumed, and I enjoyed the sudden bitter odors of wet leaves and cement. Passers-by didn't share either my equanimity or my equine happiness. Some looked on fearfully, others crossed the road to avoid me. A young woman put her hand to her mouth. Perhaps I brought to mind a Hollywood zombie or something that had stepped out of The Mummy's Tomb.

On the Corniche even the black kids ran away. I tried to reassure them, lurching after them with the camera held out, but that only seemed to make things worse. They shrieked, one child sitting down to bawl in the gutter. An old woman came running out of a church with a mop. Was it because I looked like someone who'd lost the side of his head to a mortar shell? Was I taking them back to harder times, terror from the skies, abrupt bereavements? But humankind could bear very much reality; it could bear the worst of it. The woman waved the mop in my face, driving me off, and I stumbled at the roadside curb, where the traffic was thickest, sprawling across a windscreen. The man behind the glass was open-mouthed, his cigarette falling into his lap. We had a strange meeting of sorts, but one that no longer had sleep as an option. One moment his eyes were wide with alarm, the next—with what subtle slow-mo gradations of feeling and realization—they were squeezed shut from laughter. I like to think that what he saw was not some monstrous, cartoonish creature who'd blotted out the sun, but one who, just for a moment, with his weirdly dressed head and mad swiveling eye, had filled the universe and made it comic.