| Jul/Aug 2014 • Travel |

| Jul/Aug 2014 • Travel |

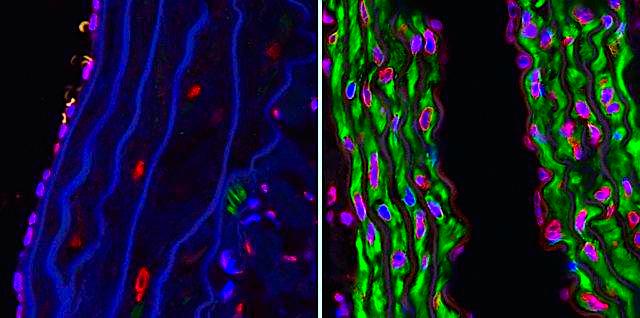

Image credit: Michelle Olive, NHGRI, Digital Media Database, www.genome.gov

Yangon, Myanmar, 2013

The streets of Yangon: potholed, uneven, choked. It's the sidewalks that bring back the past, with their tiny cracks that can widen into crumbling valleys, their uneven planes rising and sloping like Arctic ice sheets. This betel stained landscape is familiar—I discovered it 30 years ago, during my first visit to Myanmar in 1975. Yangon, it comes back now—not in the air, but in the gravel grinding at my feet.

On that other trip in 1975, I arrived late at night. Flights to Myanmar always arrived late at night. I somehow found the YMCA, a dilapidated hostel, but an institution that continued to serve as a vibrant community center. Students went there for English classes. The piano was in constant use, its overworked sounds echoing up and down the halls. I remember lying in bed that first morning and hearing a surprising musical style. The player galloped with his right hand, creating rhythmic patterns that enticed my imagination. I was a student of music and knew something of its mysteries and its discipline, but here was a breadth and range of subtlety and mystery built along new lines. The uniqueness of Burma, there in my ears, within my first 24 hours.

Today I pick my way down Pansodan, one of the straight streets cutting through the old downtown. It's mid-morning. The brightness of the sky is searing. Pansodan, stretches in a straight line toward the river. I carefully cross, dodging buses and bicycles. Now I stand on the corner of Pansodan and Maha Bandoola, next to the crumbling Telegraph Office building. Through the street sounds I make out rock music. In an instant I am caught up once again in a web of enchanting music. This time it comes from two black-clothed speaker boxes nailed to a tree, blasting rock'n'roll. I follow one chorus; it's not noise, it's good stuff. The guitar work is clean. Nothing mechanical. The riffs are timed perfectly to meet up with the downbeats in a play of sweet anticipation. The drummer and bass are tight. As I listen I can imagine them eyeing each other's every movement. Lots and lots of practice in there. The singer's gravely voice, filled with menace and power, blends in with the guitars in a way I've never heard. I am struck: yes, they're following the rules, it's hard rock, and, still, the Myanmar people take these instruments and create a new world order.

I stand on that corner for three or four more songs, each in every way unique and competently played. All around me are stalls selling lunch: a fruit vendor cutting pineapples and papayas, a noodle guy pouring broth over the small bowls of rice noodles the Burmese love. Pigeons gather under the grey and green trees, drinking water from tubs and pecking at scraps. Some of the pigeons follow me as I move down the sidewalk.

The Telegraph Office looms to the right. The building holds its bulk in the upper floors, reminding me of a barrel-chested longshoreman. However, it is no mere monument. In Myanmar all the old colonial structures, many over 100 years old, still serve as the scaffolding of everyday life. Official business takes place on the upper levels, real activity on the lower floors, in the basement doorways and half-submerged stairwells leading to tiny printing offices, Western Union desks, stationary provisionaries, and shadow-filled bookshops. And in front on the sidewalk, a library of the street. Tented stalls sell pamphlets and dicey reprints in English and Burmese, a thriving second hand trade. Printed on cheap yellow paper, the jackets replaced by hand-written labels, each book hangs on a thin string on a wooden rack. Stacks of the hand-made books, tied with strings, mark the fringes of each stall.

I glance up at the Telegraph Office's main entrance. The round, white columns are half discolored by black stains from runoff, the silt that streams from the sky every day, year after year, spraying mold over half the walls. I remember these images from my first trip, too: this is the patina covering all Burmese buildings. On that first morning in 1975, I took a pedicab down streets uniformly painted with this moldy brush. There was then no evidence of electricity, nor were boardings of commerce strung onto the sides of buildings; no motorcycles struggled to pass, no restaurants or fruit stalls existed. Back then every road led only past a few decrepit relics of the colonial period. I remember how my driver stood high and leaned his whole body with every push onto the pedals. Sweat streamed off his shirt onto the dust of the street. The streets were slow-motion whirls of beige and black as people in doorways and on sidewalks rose from sleep, each staring ahead in the state of silent grace given to every person when they first awake. They looked through me with a cutting blankness, transfixed by the unwelcome wind that had disturbed their interior dreams.

Today the city is clogged by blue and white buses and three-wheeled tuk-tuks. Like any other city in Asia—like every city in Asia—there are vistas of chaos and noise, each person following an idea of determined progress. Yangon's transformation into a commercial hub is well underway by now.

Further down Pansodan to the left, the Customs House, yet another imposing colonial structure, this one refurbished and all white, without stains. Banks line the street here. Each dark doorway offers a glimpse of cages with bars and wire mesh. I can make out only a suggestion of activity within: people changing money, sending cash by bank transfer. These operations are the same in banks all over the world. The rest, the Private Banking schemes, the short selling, the bundled subprime mortgages from my world, all so remote. I walk on. Easy for me to think this way, that innocent transactions I see in this place are somehow pure and immune from the schemes of Wall Street, with cash in my pocket.

And here, on the sidewalk, something else draws my attention away from that world. Now, in front of me: at least 100 bags, laid out neatly in rows of six, a complete display of traditional medicine, each herb and root wrapped and carefully labeled. Some hold black seeds. Some are crumbled dried leaves. Some are hard, desiccated berries, or hollow roots, or knotted vines in rusty hues, or chunks of bark. Two men sit nearby discussing business—their seriousness shines. The one in a black and white checkered shirt and tight green Burmese sarong, the longyi, sits on a stool and gestures with both arms. The other listens. He wears a blue baseball cap and purple pants and plastic sandals. This is trade, carried out half through words, half through body language, a transaction everyone can understand, the marketplace devoid of false fronts, the product there to see.

I realize, though, how each item carries its own history of labor. Each medicinal plant was carefully cultivated and selected, each piece carried down from a hill or up from a valley, on a bus or in a cart, in someone's pocket or in an overstuffed bag; each was traded several times before being washed and labeled, to finally land here on Pansodan under the street trader's gaze. And I know, too, that one of these two players may possess more information than the other—asymmetries are inevitable. I want to think of the two parties as being equal. Maybe I'm sick of a rigged world economic system riddled with inequality.

Further down the street, high in a tamarind tree, I notice a small spirit house, its wood boards loosely tacked together. The front is open to expose the Nat, the spirit staring down Pansodan, straight into the world. A pouting, comely female face: sweeping eyebrows drawn in arcs, thick lashes, bangs, an open, broad-spread nose, full cheeks, fleshy. She wears a green, net-like robe flecked with gold. Dried flowers adorn her chest. She holds her hands at waist level, palms up, ready to receive. Someone keeps her cleaned, keeps the house from falling apart. Someone still wants to satisfy her. The rest of us walk by uncaring.

Finally, Pansodan meets The Strand, the large, British-built road that runs along the Irrawaddy. The river is clogged with barges, its banks lined by dusty warehouses. I cross the road and stand unprotected in the midday sunlight. Big, dusty trucks rumble behind me. I look up Pansodan, that vector of jarring concrete extending corner after corner, a dart piercing the city's heart. It's so full of life, I want to imbibe it all. I would reach both arms across and lift it high, arching my back, and let all its raucous movement slither into my throat, all the cracks and stains and moldy spores and people looking serious, following their convictions. If I could, I would absorb all that earnestness of the city, the busy-ness that fires us up, yet lulls our hearts and pulls us apart.

I glance up at the sun. She bears down, unrelenting. I close my eyes. I sense then an alternate sky, one streaked through with the pinks and golds that form over the river at sunset: a calming, opposing force to the grinding busy-ness of Pansodan. This street in the sky fans off in thick streaks. Up there I would plant my feet and open my arms in joy. My limbs would tingle with vibrations, with all the colors and sounds I have glimpsed here in Myanmar over the years, those realms at odds with the crumbling sidewalks along which I roam, day after day, in disappointment. What sounds and rhythms flow unperceived, echoing through the receiving mind. Oh, what movement riles these skies.