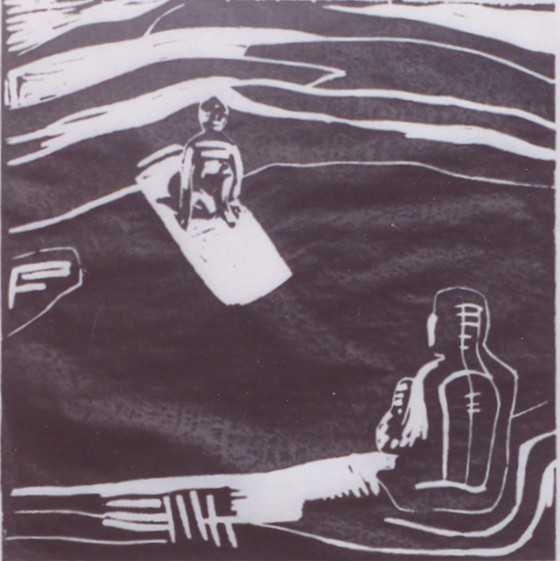

Art by Janet L. Snell

The beginning of June, 1987. Greenspan was taking over the Fed from Volcker; Webster, the former FBI chief, had taken over the CIA from Casey, who had resigned and then died; in the American League East Toronto had taken over first place from the Yankees; and from the sound of things, the cicadas were taking over Baltimore. Bridgewater lay on the sticky green and white rubber strips of a chaise lounge by the side of the Wyman Park Pool Club pool, flipping through Time Magazine, glancing at news items with only a fraction of his attention. Bored. Restless. Affected, perhaps, by the cicadas' frantic monotony, he felt his angst, too, rising to a pitch.

The high-pitched rattling of the cicadas was like the ceaseless shrilling of maracas, a constant sound swelling and subsiding, coming in waves, a shrill chattering sometimes so intense Bridgewater thought his eardrums would burst. He could feel the pulsing throb as something actual, of which the penetrating noise was only a single manifestation: some elemental force of nature threatening to run amok.

Across University Parkway, on the bumpy white stucco walls of a building owned by Johns Hopkins, Bridgewater could see them clustered like dates. They shone brownly with the sheen of dried fruit. Their squished bodies, like smeared raisins, littered the wet cement floors of the cabanas where people changed into their bathing suits.

In the "Milestones" section, Bridgewater read that Danny Kaye had died. Although he already knew this, reading the notice in Time made him feel gloomier still. Another Jewish humanitarian bites the dust. Frowning, he looked over the edge of the magazine at a cicada on the gray cement wall of the men's shower room. Its transparent wings, textured like a shed snakeskin, shimmered with cellophane wetness. Frangible shafts of light broke and merged kaleidoscopically, reflected from their shiny surfaces, and a vein of bright orange-red, a sort of racing stripe, laced the wings' upper edges. A real work of nature, cicadas. You saw them on sidewalks everywhere, wrapped in their cellophane cloaks, orange-red ribbons defining the edges like woven trim. High-tech Draculas.

The older cicadas likewise had a chilling effect: resting on curbs or clinging to trees, plump as prunes, benign as turtles or frogs sunning themselves on rocks but more intimidating because less familiar, they had those red, bulbous eyes like grains of colored sugar candy making Bridgewater think of omniscience.

An odor of cedar shavings at the pool carried with it an image of a pet store. The sharp, pungent odor teased Bridgewater's nostrils so he almost wanted to sneeze. The pool, advertised as L-shaped, actually resembled a lopsided J. The odor came from the trees that, beyond a high white fence, buffered the pool from the street. A little oasis in the middle of the city, invaded by cicadas. Mainly conifers—not a cedar in sight, except they were all evergreens, weren't they?—those tall pines were the source of that earsplitting din. The cicadas clustered in the trees, guerrilla warriors waiting for the moment to attack. They swooped around the pool and sometimes landed on the half-clad sunbathers.

The rubber strips of the chaise lounge stuck to Bridgewater's back. His sweat made them slick and stinging. He jounced a little. Like a trampoline, lacking stability and balance. Or did his impression of a lack of balance come from a different source?

A story in Time about Mount St. Helens seven years after the volcano erupted caught Bridgewater's restless eye. Had it really been seven years? Yes, that was the year he and Zippy had bought the Toyota Tercel. The mysterious, almost magical power of nature intrigued Bridgewater. Unfathomable power. You started to think puny mankind really could subdue it, and then some awesome, uncontrollable thing like an earthquake or a tornado came along to remind you of your essential insignificance. Something like the cicadas served as a more subtle reminder. Craziness at the core of reality. A metaphysical principle.

Bridgewater remembered the little schoolgirls running onto the bus the day before, screaming like characters from The Birds (Bridgewater often found himself thinking of that Alfred Hitchcock movie those early weeks in June).

"One flew in my face!" shrieked a little brown-haired girl in a pleated plaid skirt with an oversized safety pin. She'd looked like a plastic doll.

"One of them tried to fly up my dress!" another said with horror.

"I had three of them stuck on me this morning when I went into class!"

"Eeeeuuuuwwww!" A little girl with freckles made a face.

Out of the window of the bus, Bridgewater watched an older woman standing on the opposite streetcorner, swatting at the air with her purse as she stood waiting for the bus going the other way. Bridgewater knew she was swatting at a cicada, even though he could not see the insect with his own eyes.

"They make that noise by rubbing their legs together. It's the males that do it," an old black lady sitting two rows up said to her seatmate.

"It's in the Bible," her companion replied. "The swarm of locusts. Moses was in Egypt, and he told Fay-row God was gonna send a plague of locusts!"

Moses, Bridgewater thought, as if caught by surprise. The shy, stammering leader of the Hebrews in Egypt, the reluctant representative of the people, a hard-luck case who only got a brief glimpse of the Promised Land in reward for all that work. Husband of Zipporah.

"Seen 'em 17 year ago back in '70; seen 'em 17 year afore that in '53; seen 'em 17 year afore that in '36. I remember. I seen 'em," an old white man on another seat was saying to the young man in his 20s who sat beside him. He nodded with sage conviction. "Don't remember seein' 'em in '19, but I musta been old enough. I was ten in '19." He nodded again. "Yep, I seen 'em."

"Notice you don't hear them when it rains?" the younger man said. "Once it starts to get hot, though, those fuckers start to chatter like rattlesnakes!"

"Doug!" a plangent female voice cried, awakening Bridgewater from his reverie. He looked around. A college girl in a bikini was pleading with the lifeguard, her whine in harmony with the cicadas. "What'd you do with the kickboards?"

Bridgewater watched the lifeguard, a tan, broadshouldered college boy, reach behind a counter and bring forth a blue kickboard with the white outline of a dolphin drawn on it. Like a barnyard rooster, Doug strutted about with the kickboard, teasing the girl, refusing to give it to her.

"Dooooo-uuug!" she said in a reproachful singsong. An elaborate mating ritual was going on here, the dominance and submission of animals in nature, the preening of the male and the tail-lifting of the female. The girl stood there helplessly, her arms at her sides. Take me.

Just then a cicada flew into the sensitive flesh under the girl's left breast, and she shrieked, alarmed.

"I hate those damn things!" she cried.

"Hate them?" Doug said, handing her the kickboard. The cicada had spoiled the mood. "Hell, why don't you eat 'em?"

"Did you say eat them? Oh! Don't make me sick!"

"Sure," the lifeguard said, smiling boyishly. "Marinate 'em in teriyaki sauce and fry 'em, or put 'em in tacos instead of ground beef. Roast 'em and then crumble them up over ice cream."

"Oh, yuck!"

"They serve 'em over in Mount Washington. At Café des Artistes."

"No thanks!" The girl walked over to the pool, her butt twitching an invitation and a promise, and dove in. Bridgewater was sure she'd be back. His conviction made him anxious. What if she could simply walk away?

Around the pool the sunworshippers lay on chaise lounges with headphones over their ears and shades covering their eyes. For the most part they seemed blithely unaware of the cicadas. The bugs were a nuisance on the street, but they would soon die with nothing left but a memory for the next decade and a half. Their lives were so brief, a frantic mating ritual, somnambulistic; their maturation, after 17 years of dormancy, was so accelerated you could almost literally see the process happening before your eyes, the metamorphosis from pupa to adult. "Glut thy sorrow on a morning rose..." An almost frantic impulse to cram all of life's essential processes into the briefest possible duration. You'd scream, too!

The sexual tension in the air, Bridgewater thought, might only be a symptom of his loneliness, an illusion fostered by the jungle-like whir of the cicadas. Or there might be some metaphysical basis to it, some crisis in his own developmental process, paralleling that of the insects. He was 35, Dante's age at the beginning of The Divine Comedy.

When I had journeyed half of our life's way,

I found myself within a shadowed forest,

For I had lost the path that does not stray

Dante's mid-life crisis was more than male menopause; Bridgewater suspected his own was, too. After eight years of marriage, Bridgewater's wife had left him. She'd been gone for more than a month now, and lately Bridgewater had begun to yearn for female companionship. But not only had his wife left him, she had left him for Mick Jagger. That was the crazy thing.

In Time Bridgewater read an account of the West German boy who had flown a tiny Cessna into Moscow's Red Square. In the air, the cicadas resembled helicopters or hummingbirds. You could see their wings beating. The clumsy, graceless whirl. Then on the sidewalks, the already spent ones, dying, frantically beating their wings in a futile effort at flight, seemed like airplanes shot out of the sky, sputtering to a stop. Birds with broken wings.

What a crazy thing to do! Fly an airplane to the Kremlin. The kid who did it was sure to go to Siberia or someplace. What a price to pay! The kid claimed he did it in the name of peace. A rational-sounding excuse for what was essentially a fraternity boy prank. Well, what defined craziness, anyway? Who could say?

The doctors Bridgewater had spoken to had told him his wife, Zippy, "suffers from the delusion an unattainable man of high social status is passionately in love with her. She desires a sexual relationship with the man." Exactly what he had told the doctors! But they went on to give the disorder a name: "de Clerambault Syndrome." They were not sure if the disorder was a clinical entity in its own right or a variant of one of the major psychoses. Under the present diagnostic system, they said, her disorder (they loved to refer to this as a "disorder," like calling shit a bowel movement) was best classified as a manifestation of a more general psychopathological condition, most likely paranoid schizophrenia.

Accusingly, one expert called Zippy's disorder a defense against feelings of depression and loneliness, perhaps a reaction to feelings of rejection. Feeling unloved and unlovable, she tried to overcome this threat to her ego, these narcissistic injuries, by turning them into grandiose fantasies.

But was it Bridgewater's fault they weren't able to have a baby? And why did they think Zippy felt guilty? Was she even "sick," after all?

Another specialist handed him the tired old Freudian line. Zippy sought a safe, eroticized father figure.

Mick Jagger, safe?

"Safe because unattainable," the doctor explained, miffed at Bridgewater's incredulous tone, his lack of respect for scientific hypotheses.

Yet a third explained the problem as a defense against homosexual impulses. Guilt explained everything to these guys. In any case, they had all prescribed mild antipsychotic drugs (drugs Bridgewater's brother had peddled back in high school). The drugs seemed to help at first—at least Zippy stopped sending Mick Jagger two dozen letters every day and had otherwise functioned normally at her job and in social circumstances—but then just over a month ago, she had just taken off. One day at the end of April, she just hadn't been home when Bridgewater got there. A few days later he received a postcard from some island in the Caribbean.

Bridgewater sighed, looking at the girl in the pool. Feckless, without real vitality despite his big shoulders and his tan, the lifeguard, too, followed the girl's movements, a big dumb smile smeared across his face. He had the inside track to the girl's affections. But damned if Bridgewater was going to be jealous. He turned back to his magazine.

"Excuse me, is Saul Bellow's new book reviewed in that issue?"

Bridgewater turned to look into the eyes of the red-haired woman on the chaise lounge next to his. He thought he recognized her from someplace. Laughing green cat's eyes stared familiarly.

"More Die of Heartbreak? I don't know. I think so."

"Can I see it when you're done? I'm doing a paper on Saul Bellow for a summer school class at Hopkins."

"Oh yeah?"

"The theme of plants in his later novels. Plant life, vegetable consciousness. Like deep sleep."

"Sounds interesting." Bridgewater gave her the magazine. Sounds like a crashing bore!

"You're sure you're done with it?"

"Sure." Couldn't he say anything but "sure" and "oh yeah?" This was his chance to meet another woman. She had clearly dropped a hankie in asking for the magazine. Bridgewater knew his mating rituals, all right. Talk about tail-lifting. Where had he seen her before?

She gave the impression of being athletic. She probably worked out on metal and naugahyde equipment in a sweat-smelling fitness club somewhere, Bridgewater guessed, maybe played racquetball and squash. Her strong-looking legs were tanned from exposure to the sun (or a tanning booth); flat against her muscular torso, her breasts, the contour visible underneath the peach-colored nylon bathing suit, reminded him of two country-fried eggs. Wholesome. "Good for you." Momentarily, he envisioned oozing yellow yolk on the fabric staining the pinkish orange swimsuit blue-green. Crazy. He blinked his eyes to clear away the hallucination. He eyed the woman critically.

Attractive, yes, but her rich dull red hair would be brassy and toneless in another few years, and with that sort of coloration, she would most likely develop moles and warts on her arms and body. But then, he was no great shakes in the looks department himself, would be even less a prize as time went on. Bridgewater was a slender, bony man with knobby knees and fine blond hair sparsely covering his shins and thighs. His hairline was receding; he had a bald spot on his crown. Looking at him, you thought of scaffolding or collapsible aluminum porch furniture, the legs buckled under. Still, he reserved the right to assess women from the perspective of a teenage cocksman. Certainly at this moment in time, she was a delectable piece. No argument there. But where had he seen her before?

"You go to Hopkins?"

"I'm in a graduate program in English. I took a few years off after college," she explained. "I taught English in high school for a while."

Mid-to-late-twenties, Bridgewater calculated, the facts dovetailing with the appearance.

"And you're doing a paper on Bellow?"

"You think it's dumb, don't you?" she accused. "Plant life. Ever read The Dean's December, the one he wrote after getting the Nobel Prize? Remember how the dean was a sucker for the cyclamens back in Chicago?" She did not pause for a reply but went on without taking a breath. "Flowers are so complex but so benign. The appearance of design in nature without any apparent intelligence behind it. Of course, the same facts used to be used to prove the existence of God." Her crazy bookish talk both challenged and repelled him.

"Maybe it's innocence he's getting at, the innocence of an absent-minded intellectual in human affairs seen as analogous to the innocent growth of plants. Mystic signs of an unconscious order." She seemed to be talking more to herself than to him, but still she eyed him closely, intently, a cat watching a bird.

"Or like the cicadas," Bridgewater interrupted. "Buried under the ground for 17 years, and then they wake up like Sleeping Beauty to a full-fledged sex life, so natural and unpremeditated it's just like breathing."

"Sure, like the cicadas," the woman said, turning away, and Bridgewater felt from her curt reply, the apparent boredom and distaste, that he had lost points. What had he said wrong? Did he sound too sarcastic, as if he didn't take her seriously? Her aggressive manner put him off balance but attracted him at the same time. He didn't know much about Bellow. Better leave the topic alone and go on to something else.

"You come here often?" he asked.

"Depends on what you mean by often."

The coy response both pleased and annoyed Bridgewater. He shrugged. "Do you come here after classes or something?"

"I live over there," she said, indicating an adjacent apartment building with a nod of her head. "It's part of the rental agreement. I get to use the pool. How about you?"

"I just joined."

"Did your wife join with you?"

Bridgewater looked down at his left hand with the gold band on it. Then he remembered: he had seen this woman at the store where he bought his monthly bus pass—a dirty, bleak-looking building with MONEY ORDERS FOOD STAMPS CHECKS CASHED painted in loud red letters on the whitewashed brick outside and glowing in eerie blue neon in the window. He and Zippy used to go in together at the end of every month to buy bus passes. They owned a car, but they preferred public transportation.

"No, she left Baltimore about a month ago." He shrugged. What could he say without exposing the great gaping hole in his heart? "She was suffering from de Clerambault's Syndrome."

"Rambo?"

Was she joking? "Maybe I mispronounced it. It's a mental disorder." He shrugged again, hating himself for using that term. Disorder.

"She's in a hospital or something?"

"Or something." After an awkward silence he made a lame clarification. "She just... went away." He changed the subject. "So you're doing a paper on Saul Bellow." Wrong move! He wished he could take it back.

"He has this thing about your elemental self, the way you really are."

"The way you really are?"

Agitated, she gestured with the Time, which she had rolled up into a baton, waving it in a semi-circle over her head, and Bridgewater could have sworn her green eyes bulged out past the tip of her nose, big as traffic lights. The cicadas' shrill noise seemed to foster hallucinations. "A basic harmony. An elemental serenity. Mystical and passive, feminine. Like vegetation. Bellow is annoyed by the oscillation of modern consciousness. It's like the restlessness of high-speed computers constantly polling terminals for input, only it's the senses and memory being polled for some new pocket of stimulation, something to fasten the attention on, some nugget of interest. There are 24 hours to be gotten through every day, after all."

"Too bad we can't live like the cicadas, eh? Just do, don't think." He tried to be agreeable, conciliatory, but apparently he had just put his foot in his mouth again.

"That's not what I mean." The hollowness of her tone made Bridgewater flinch. "I think there's already too much doing and not enough thinking."

"Just not enough innocence, huh?"

Abruptly, she changed the subject. "Your wife. Where did she go?"

The woman was crazy. Why not try the truth out on her? "Zippy? She went off to marry Mick Jagger."

"Zippy? That's her name? Like the comic strip? Zippy the Pinhead?"

"It's short for Zipporah. A Biblical name. Zipporah was Moses' wife. The name means 'little bird.'"

"Moses' wife, eh?"

"She's Jewish. I'm Jewish."

"You? Jewish? Come on! You tell me one lie after another! With that little upturned nose and blond hair?"

"I converted. It's a long story."

"You converted, and your wife is marrying Mick Jagger. I hope Jerry Hall has something to say about this."

"All right. I was lying. She's at home. She doesn't like to swim or sunbathe. She didn't want to join." He was sorry now he'd gotten involved in a conversation with a crazy woman. His loneliness had gotten the better of him.

"I thought so. And you aren't really Jewish, are you?"

"What does 'really Jewish' mean?" he asked, exasperated. His mother-in-law had a hang-up about the same subject. She claimed the Torah was very explicit on the subject. Who was a Jew, who was a Jew permitted marry, what might happen to a Jew if he or she married a gentile. She said the Torah denounced intermarriage in no uncertain terms. When Bridgewater pointed out the Torah was full of "mixed marriages," that even Moses had intermarried—Zipporah was the daughter of Jethro the Middianite—Edith Feldman snapped back that Moses married Zipporah before the Hebrews had received the Torah on Mount Sinai, and what's more, Moses had not been allowed to enter the promised land.

"Where does your wife work? Zippy?" the woman asked, changing the subject once again. Talk about the oscillation of modern consciousness. But she could probably see the coy exchange was a cul-de-sac. Ran off to marry Mick Jagger. How absurd!

"Social Security." But why, Bridgewater wondered, was she so concerned about his wife?

"I knew this woman who worked at Social Security," the red-haired woman said. "Hated it. Absolutely hated her job. She worked in a building there where everybody complained their sinuses were being ruined by the office environment, the recycled air. Big clots of gunk and so forth in the nasal passages. Gross."

"Zippy doesn't seem to mind it much." He tried putting on a laconic manner in a feeble attempt to bring the conversation to a close, but face it, he was starving for conversation, even this crazy exchange. How long had it been now? He felt like a Trappist monk.

"My friend at Social Security said her job was very paper-intensive." Which meant, Bridgewater guessed, she scribbled a lot, made a lot of false starts, wrote a lot of memos. A writer? A computer programmer, like Zippy? A bureaucrat?

"Well, what is your name, anyway?" he asked. A cicada came veering toward his face, and he felt an instant of irrational panic as he slapped at the insect. "God damn bug," he said, embarrassed to have lost his composure. He noticed the cute girl in the bikini had finished swimming and was lying on a chaise lounge next to the lifeguard.

"Cecilia Nestorick."

The name sounded familiar. Nestorick. Where had he heard it before? You didn't have to give your name to get a bus pass, after all. An anonymous transaction. You told the man behind the glass partition what sort of pass you wanted, the sex of the bus pass owner and the number of zones it covered, and he quoted a price.

"We're distant cousins," Cecilia said, watching him suspiciously.

"Excuse me?" Bridgewater said, puzzled. "Distant cousins?"

"Weren't you going to ask me if I was related to Roger Nestorick? Everybody else does."

Bridgewater's interest revived. So Cecilia had similar problems, he thought, taking heart. Crazy, but on the same wavelength. Roger Nestorick, the infamous sex offender who had molested more than a dozen boys and girls—not to mention terrorizing half the household pets in Waverly, if you could believe the stories—had been convicted on six counts in January after a sensational trial. Zippy may not be an outlaw, she may not even have been crazy, but the doctors had diagnosed both her and Roger as sexual nut cases. Who knows? Maybe Zippy would yet turn out to be the next John Hinckley. He had a quick image of his wife stalking the president with a gun in order to impress Mick Jagger.

"Oh yeah. Now I remember. I followed the case in the papers."

"You and the rest of the city."

"My father knows the prosecutor pretty well," Bridgewater explained.

"Your dad works for the government?"

"City Hall. God, it must have been pretty trying for your family." He tried to sound sympathetic.

"Tell me about it. My mother's on committees down in Annapolis and Washington trying to get research grants and lobbying for money for mental health care."

"Your mother?"

"I said his mother."

He wasn't having auditory hallucinations, too, was he? He thought about correcting her but decided not to. Her mother, his mother. What was the difference? Bridgewater shook his head. sympathetically. "So what's become of him, anyway? Was he committed or something? Sent to a hospital?" His curiosity overtook his tact (Besides, hadn't she asked personal questions?).

But Cecilia took it in stride. "Well, of course he was institutionalized. He'll be in a halfway house soon, though. They've tried a number of treatments on him, from psychodynamic psychotherapies to masturbatory satiation techniques to drug treatment."

"Drug treatment?"

"Antiandrogens. They're supposed to lower the blood level of testosterone."

"Sort of a cold shower in a hypodermic syringe, eh?"

"Testosterone is associated with sexual desire and sexual aggression. The drugs he takes decrease sexual fantasies and the capacity for erection and ejaculation."

"You sound so clinical."

"What do you want? The National Enquirer?"

A cicada landed on Bridgewater's bathing suit. He brushed it away.

"Somebody ought to give antiandrogens to these creatures."

"That's nature, not fantasy."

Irritated by Cecilia's didactic tone, Bridgewater finally snapped. "You want natural?" he said. "I'll give you natural."

Cecilia hissed, disgusted. Chastised yet piqued, Bridgewater became insolent. "I bet if you roast them and sprinkle the ashes on a salad it might have an aphrodisiac effect. Like Spanish fly. That wild sexual impulse is clearly genetic, so maybe it would affect humans if we ate them, what do you think?"

"Hah!" Cecilia snorted, sensitive to Bridgewater's aggressive tone. Her green eyes sparkled, vibrant with lunacy. "You know what they make me think of? The dead ones? They make me think of those Halloween candies. The orange and black marshmallow things with the sugar coating."

"They say cicadas taste like shrimp."

She looked dubious. "Probably they taste like whatever you season them with. Garlic or pepper or butter or whatever."

"I bet they get you pretty hot." Bridgewater felt reckless and lewd, carried away by the crazy talk and the cicadas' screeching noise.

"Maybe if you season them with curry powder or coriander."

"Are you feeling hot?" Bridgewater said suggestively. "Would you like to go for a swim?"

"Why don't you just cool it?" She regarded him contemptuously.

Excited as a cicada, confused by the fast pace of the repartee, Bridgewater leaned over to Cecilia so his lips were only inches away from hers. A few others around the pool glanced their way. Doug, the lifeguard, suddenly pointed his nose in the air like a terrier, sensing a hunt. The girl in the bikini's mouth dropped.

"We could go to your apartment over there. We could probably cool down there pretty well."

"I think you've got the wrong station!" Cecilia said toughly. "Why don't you try changing the channel?"

Amazing! Bridgewater had mentally used a similar metaphor to assess his vulnerability to the girl. He thought he was on the same wavelength, but his carnal desire had jammed the broadcast, and now she was tuning him out.

Bridgewater stood up and walked to the pool. He felt dizzy, vertiginous, reeling like a dying cicada spinning to the earth. He dove into the warm, scummy water, but with no sensation of relief, shamed by his behavior.

But then he noticed he could no longer hear the ceaseless shriek of the cicadas. He had escaped the noise! Staying under as long as he could, cut off about as completely as if he were in an isolation tank, Bridgewater felt a kind of purgation take place, a cleansing of his emotions. He stayed under until he felt his lungs were about to explode.