Photo courtesy of NASA's image library

Several weeks ago, I spotted an unidentified spinning object on the far end of my daughter's kitchen. "What in the world?" I said aloud.

"She wanted a record player, so I got her one," my daughter's wife explained.

"But why?"

My daughter's thirty-two. She listens to music; she's just never shown any interest in audio, despite or because of growing up around my on and off speaker building hobby. The CD began replacing vinyl in 1982. My daughter was born in 1990, or roughly when I started buying silver disks read with a laser, then decoded with a DAC circuit, and stopped buying the black ones read with a vibrating needle, then passed through an RIAA circuit, then a pre-amplifier. When she was maybe five, she once came into my study where I kept my turntable and wanted to hear it play music. I made up an excuse not to, a decision I came to regret. I was terrified my kindergarten-aged daughter would be slipping into my study and trying to play records herself without going through the myriad rituals needed to protect the vinyl and the tweaky alignment of the phono cartridge. I chose protecting my toys over indulging my own child's sense of wonder. She never asked again.

My daughter's device is decidedly more record player than turntable. It's almost completely plastic and includes tiny speakers with a less than dynamic amplifier, definitely not part of the audiophile retro-craze for single-ended vacuum tubes, horn-loaded speakers, and the analogue virtues of vinyl. She has just two records: a Beatles album and one by Adele which I'm pretty certain was recorded digitally. New vinyl records are currently $25 each, or considerably more than what CDs cost new. Audio CDs are now essentially worthless. "Perfect sound forever" quickly gave way to "for a small monthly fee, stream whatever music you want, anywhere and anytime." If you have Spotify or Tidal, you have the same enormous music collection as every other subscriber. Who needs physical media at all? In the meantime, she refused my offer to get her better speakers and amplifier. I'm pretty sure how it sounds isn't the point for her. It's more a matter of it making music at all. Reproducing music by selecting a record, prepping it, and cueing a stylus may not physically have much in common with producing music by bowing a violin, but it's much closer than casually telling Alexa to play a Bach Partita just after you've used it to check the weather or order toilet paper. Vinyl records demand a level of attention no longer needed for digitally reproduced music; you listen more closely because you have to put so much effort into setup and maintenance.

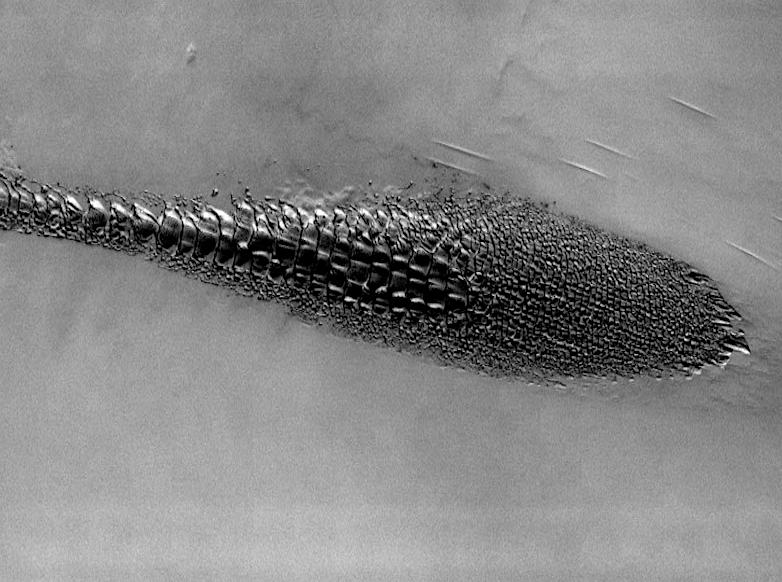

The vinyl record comes from the electro-mechanical age. Although handheld calculators came much earlier and the Apple 2 computer came slightly earlier, the CD player was most American households' first significant digital item. My grandfather, who was born before radio and cars, had a fascination with mechanical clocks. He collected them and loved synching them, winding them, and keeping them dust free. He, however, had no interest in electric clocks. My parents bought a standing grandfather clock with 30" brass pendulum for their first house in 1960. My grandfather was so taken with it, they wound up gifting it to him—one of the few presents I remember his truly loving. He could easily have bought his own. Looking back, I'm not sure why he wanted ours. He did fuss over the clock in ways he didn't fuss over my father. Sadly, it was stolen in a house break-in just after my grandfather passed away, three months after my father died. It only recently occurred to me that my two-plus decades of my own fussing over my vinyl-based playback chain with pre-pre amps for moving coil cartridges, stylus brushes, multiple cleaning devices, and rice-paper record sleeves expressed the same finicky pride my grandfather brought to his clocks. If there are individual genes for disliking cilantro, being annoyed by the sounds of other people chewing, or for excessive ear wax buildup, I suppose my daughter's record player could be the fourth-generation expression of some gene resulting in a fascination with gadgets—possibly the same one that separated modern humans from their Neanderthal cousins.

Mechanical objects are inherently physical and, as they evolve, tend to revel in their own complexity and specialized function. Digital objects, at least outwardly, tend to do the reverse by getting smaller, sleeker, and simpler to operate. While they remain physical at some level, their essence has become metaphorically ethereal. Consider "The Cloud." At the same time, devices like the cellphone keep growing new functions. What used to be separate telephone, music player, video player, camera, movie camera, answering machine, datebook, bank book, and post office box have coalesced into the pocketable "smart" phone, the device of choice for all of these tasks. Compare today's phone to the Swiss Army knife, so popular in pre-digital times, which managed none of its dozen or so functions even competently (did anyone ever find a use for that plastic toothpick or manage to pick up anything with those tweezers?). Unconsciously, we now gauge the age of various devices by the absence of buttons and dials, and by the number of ways it can interact with other classes of gadget. Thanks, Steve Jobs!

Music is just one form of human expression crossing the analogue to digital divide. The "written" word is in the midst of a similar shift. There's the obvious like the disappearance of penmanship from elementary school report cards and the slow upward creep of reading electronic instead of paper books. Traditionalists insist paper book sales are holding steady and even growing, but when you throw in reading modes like social media and texts, far more words are being consumed and reproduced electronically than on paper.

The overt differences are clear. The e-book separates the craft of book production from book writing. Bindings, paper quality, choice of font and margin were once agonizing decisions for hardback presses. With e-readers, fonts and margins are chosen by the consumer, not the publisher. To lovers of the craft, e-books aren't properly cooked, they're microwaved. Paper publication is still the mark of legitimacy with the written word, but traditional print publishers, whether books, newspapers, or magazines, have become gatekeepers for a landscape that's eschewed fences or walls or gates: anyone with an Internet connection can potentially reach millions of people through a range of outlets, avoiding the gatekeepers altogether. The digital age has severed the "written" word from the physical moorings of the printing press.

When my wife and I were selling our house, we contacted a prospective agent who presented us with his 45-page personalized marketing plan two days later. Forty-two of the pages were clearly copied and pasted, so we went with the agent who used a drone to take photos and posted a video tour online. Meanwhile, ordinary people are generating "writing" in Costco-sized portions every day. It may be a written-word world where all restaurants are Taco Bell, but the written word definitely isn't going extinct. It has, however, lost object constancy. Electronic words have a virus-like quality: they change form, get chopped up, spliced, and re-attributed, mutating often in disturbing ways. They're both disposable and strangely permanent. If my email inbox is typical, so much of it is read once or not at all, yet it clings to existence, gets found, and suddenly, under the right conditions, reproduces uncontrollably like some fast-acting cancer. Just ask Hillary Clinton, Hunter Biden, or George Santos.

It's hardly surprising trust in the onscreen word has never matched its paper counterpart. Anything that appears and disappears as easily as online text can barely lay claim to being real. Once screen tools moved from fixing your spelling (typos) to debugging your grammar (voice), the matter of authorship or trust in it became an issue at the educational level. The appearance of ChatGPT, online software that can take a prompt and turn it into a credible essay or story without further input from the human user, brings the matter of authorship even closer to the brink.

In the Top Gun sequel,Tom Cruise's character steals an obsolete fighter plane for the movie's final sequence and asserts his dogfighting aerobatic genius. Other than the usual Pentagon permission issues, there's a reason he has to steal an older plane: current day fighter jets are "fly by wire." Where pilots once made the adjustments by hand, modern-day fighters go so fast and are so complex, most of those decisions are now done by computer. Even the most skilled pilot can't keep the aircraft stable without computer assistance. Similarly, we went from 1980's assurances that no computer program would ever beat a grandmaster at chess to Big Blue defeating world champion Garry Kasparov in 1996. In a similar length of time, we've gone from "Can we trust onscreen words?" to "Can we even tell if they were composed by a human?"

I suspect a word processor will "write me" better than me in the near future. In any case, it'll certainly do it more efficiently unless someone writes a virus for it simulating writer's block.

Making writing "easier" has also created an interesting paradox: now that words can be produced and reproduced with a simple cut and paste, the cultural power of the unadorned written word has declined. Each time we moved and looked for a new house, we noticed the increasing absence of bookshelves as a feature of the typical American home. My father loved to read, but my mother wasn't much of a reader. After my father died, my mother remarried a very nice man who wasn't much of a reader, either. She took down any photos of my father, moved his possessions out of her house, but she kept the books in the bookshelves. I asked her why she kept books she had no intention of reading, and she told me it was about "making the house look right." That may not have been her only reason, but it's clear maintaining the pretense of "reading" no longer bears much relationship to staging "middle class" respectability. I suspect this has nothing to do with the emergence of the Kindle. Today, few Americans have heard of a living writer of literary fiction unless their work has been adapted for screenplay or series. We still read, but books have lost their place as social lubricant. Conversations are far more likely to start around a binged Netflix series than page-turning novel. The late Toni Morrison may have been the last celebrity literary writer known primarily for her books.

Digitization has impacted the written word at an artistic level as well. The 25-page plus (6,200 words) short story was once common in print story collections. Most online venues now set a 4,000 word or lower maximum for short story submissions. Flash fiction, once too short to be marketable, has boomed since more reading has gone electronic and more writing is essentially being given away. I suspect flash fiction still doesn't make money, but with online's negligible publication costs, that doesn't really matter. Patience with onscreen content appears to be different from patience with the printed page. I confess: I still like longer works, but I find it much harder to read multi-page texts on a website. I do notice it's better with e-ink screens, but there's something about the satisfaction of feeling all those pages turning with your fingers and the weight of the book moving from the right hand to the left. Whether it's computers or words, going digital tends to make everything except television screens smaller.

My own high school English teachers would be horrified to learn I tutor kids in writing. My shortcomings in the area of written expression when they knew me weren't due to their being bad teachers; I just didn't get it at the time. Actually, any number of types of writing still make me profoundly uncomfortable, thank you notes and birthday cards being prime examples. Over the last seven years, I've privately tried to help students write better who weren't alive on 9/11, and whose sense of history starts with 1/6/21. My students are quite ambitious. They're often really good with things like the verbal side of the SAT. They also don't read any books they haven't been assigned in school. Part of that is they take four AP classes at a time and fill up their free time with extracurricular activities with an eye to college applications. Simply saying, "Hey, I read a lot," doesn't move admissions office meters much. They're also great kids. They just don't happen to be very effective writers, and I suspect much of that is due to their growing up after words and writing went digital.

One relatively subtle aspect of digitization has been the imposition of constraints around time and metrics. For most writers, writing something well takes time and effort, something usually taking the form of multiple drafts. I frequently tell my students first drafts often suck because they're supposed to suck. They're often given deadlines leaving them with little choice but to turn in their first draft before it has a chance to be fully formed. There is the dual-edged nature of "cut and paste"; you can make pretty much anything read reasonably well, fairly quickly, with spell check, grammar check, and the ability to easily move blocks of text around. I'm not sure, however, if you can make something read really well without the deeper level of thinking and rethinking demanded by the old fashioned drafting/revision process. With word processing, the markup or correction stage becomes synonymous with "redrafting." Back in the mechanical age, you would mark up the typed document with a pen, then retype the draft from the beginning. The physical demands arguably forced you to think a bit more, and cosmetic changes were harder to confuse with substantive ones; things can now look good before they're actually good.

On the teaching side, I've seen a rise in "rubric" grading for papers. In order to grade 140 papers, the teacher needs to handle things in a manageable but also seemingly objective way. One result is a system where a student can lose three points for not getting the headers right or ten points not following MLA citation norms, but can only get a maximum of forty points for their ideas. The downside? It encourages students to adopt a checklist approach to expressing their thoughts. Good writing makes its points efficiently. Great writing provokes. The combination of digital and political pressures has pointedly taken the provocative out of writing instruction and substituted rubriced checklists.

It's just my opinion, but the best writers tend to have what some call a "voice," a unique way of making their points, equal parts how it's said and what is said. I don't think schools do it on purpose, but I've seen a lot of assignments suppress rather than promote the development of individual voice. So much emphasis is put on conforming to five paragraph essay form and properly supporting opinion with "on the nose" evidence, and so little lip service is given to individual emotional resonance and expression that the result is almost doomed to be stiff and bland. Is it possible computers can write more like humans because too many humans are being taught to write as if they were computers?

In the audiophile world, there's been a two-generation-long debate around the virtues of tubes vs. transistors and analogue records vs. digital. A debate perhaps, not surprisingly, which parallels my concerns about the shift of words from page to screen. Proponents of the newer music reproduction technologies talk about accuracy or the elimination of distortion. They'll point out the "notes" are all there, and how the improvement in the measurable specs can't be questioned. The retro folk will go on about wholeness, harmonic structure, a sense of space, the way things fit together relative to one another. They complain the newer technology is somehow lacking in soul or humanity, so much so, it's lost its capacity to be "beautiful." Occasionally, digital lovers will agree but then insist the solution isn't to go back to the old electro-mechanical ways, but rather the addition of more bits and faster processors to fix whatever's still missing. Fwiw, they might be right. It was silly to think reproducing "notes" was the same thing as reproducing notes in time, in a given space, with different orders of harmonics swirling around one another. I suspect the emotional pleasure we get from reproduced music has a lot to do with those more complex informational demands.

Even if music reproduction is simply a matter of capturing more information, I'd like to think the production of music itself will always have a mystical element. Similarly, I happen to believe voice and feeling are part of what makes good writing matter and why it's something still worth accomplishing. The movement of words from paper to screen, from "committing" thoughts to paper and then to the curious "anonymity" and impermanence of the flickering screen, may be making it harder to preserve the personal and the mystical power of words. In the face of that, it's even more critical we keep alive the notion that words can have emotional power and resonance, sometimes allowing them to survive and even flourish as the instruments we use to record them change form. Perhaps some computer program will one day out Shakespeare Shakespeare? Should we then give up trying to write? I prefer to think the effort to express ourselves in words will still be worth pursuing on our own. Millions of people still play chess. If you think about it, the computer has always been able to beat any human at any video game. It's the trying in the face of ultimate futility that just may keep us human.

Moments after my exchange with my daughter-in-law about the record player, my daughter reappeared in their kitchen. Without saying anything, she let me drop her stylus on her record. I couldn't tell if she remembered my not letting her do the same with my turntable more than a quarter century ago. We've never talked about that moment, and she certainly didn't bring it up in this one. It had been at least 15 years since I'd cued up a record. To be honest, I didn't miss it. I never liked the way listening to music was once a physical test of nerves and manual acuity. Instead, it struck me this was off-the-wall evidence my daughter is both a far better person than I am while still sharing my fascination with gadgets. We listened together to a digitally-recorded Adele, transferred to vinyl roll in the deep. I was still searching for the words to tell her as the moment spun away.