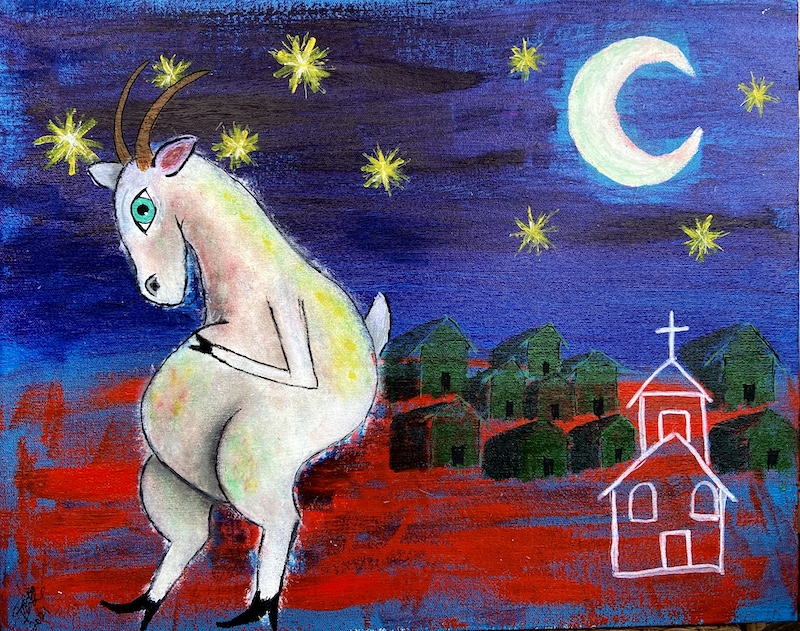

Artwork by Dale Bridges

Benedictine Mission School on the Tallgrass Reservation, 1942

Sister Walburga looked out at her charges: 47 brown faces with eyes like pieces of coal peering back at her from over their desks. The girls wore brown jumpers over white blouses, and the boys wore white shirts and brown pants. Most of them had bangs cut sharply across their brows and varying lengths of hair, boys and girls both. They were quiet, well-behaved, though the boys could get fidgety and uncooperative. They were not interested in what she had to teach.

It was October, and the lesson was Columbus. "In fourteen hundred ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue." These children had not seen an ocean. They had not even seen the inland ocean that was Lake Superior, a body of water so vast you couldn't see the far shore. All they knew of water was Willow Lake, on the shores of which hulked the large Benedictine mission complex with its three-story school, its chapel and monastic quarters.

Sister Walburga had taped to the board the three drawings of sailing ships, and beneath them in chalk she wrote the names: Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria. This is what she wanted the children to know, the dates and the names. But these children, the Chippewa, were not receptive. She had them draw the three ships on paper. Most of them drew what were obviously canoes, but with large sails coming out of them like open umbrellas or the canopies of trees. She asked them, "How could a boat like this carry an entire crew of men all the way from Spain? Look more closely at the board and try again." Some of the boys ignored the assignment entirely and drew horses with Indian warriors stretching bows to let arrows fly at their enemies. In one picture, the enemies were wearing the buckled black hats and long coats Sister Walburga recognized as Pilgrims. She confiscated this drawing and put it in the wood stove at the center of the room.

It was ten. A child asked how much longer it would be until lunch.

This was not why Sister Walburga joined the convent. She chose the convent in large part because she wanted to get away from the family dairy farm in Central Minnesota. But she also felt called to the beauty of religious life with the Benedictines. She was in heaven during her postulancy and novitiate, mostly because of the quality of the habit she wore, the heavy black material held by a real leather belt, and the coif starched and pressed in a special machine into many small pleats, the white band at her forehead and white veil marking her as a junior Sister and falling just so into even folds down her back. She felt rich, far away from the child Agatha who grew up wearing dresses made from flour sacks.

She loved the liturgical candles and even got herself assigned for six months while in simple vows to dip them with Sister Clement as part of the apiary operation. The smell of beeswax made her feel clean and holy, both in the candle making studio and in church where she watched their smokeless flickering on the altar and in sconces along the walls.

Sister Walburga had hoped to escape the kind of grueling physical labor she'd known as a child, yet the mission assignment had proven even more challenging. As a child, Agatha had picked rocks in the spring, lifting whatever large field stone came up in the heaves of freeze and thaw, rolling them onto the back of a wagon her older brother Otto drove too fast for her and the other children to keep up. Agatha hated the mud, the dirt everywhere, the backbreaking work of laundry with her mother, worse and worse as the dozen children were born in their own season and heaped more and more clothing on the pile, including diapers, all her years at home. And after her younger sister Sarah fell through the ice and drowned, her mother lost the spark of joy she'd had—and there had only been a small spark—and everything became pure drudgery.

Yet here she was, a school teacher, whose heart's longing had been for a life of prayer and wisdom, burdened instead with responsibilities for a large garden and a larger facility to keep clean and in order in uncivilized conditions. The growing season up north was even shorter than at home, and the nuns were expected to grow fresh vegetables, at a minimum potatoes and onions, beans and cabbage, squash and corn, to feed themselves, Father Henry the priest, and to contribute to meals for the students.

It was clear right away that one main purpose of the school was to feed the Chippewa children. "Food for the body, brain, and soul." That's how Sister Michael described their mission. Sister Michael, who needed no sleep, prayed an extra Liturgical Hour at three and then made the bread dough and left it to rise. Everyone woke and gathered not in the chapel but in the kitchen for Matins at five, where the only heat was the fire laid by Sister Michael, and they prayed the psalms and Benediction to the smell of rising bread. That part was nice. That part was very nice. When the children entered in the morning, they'd stop in the main hall to take a deep nose-full of the baking bread.

By the time the day students arrived, Sister Walburga, Sister Victorine, and the other teacher, Sister Mary Peter, had peeled buckets of potatoes and carrots, had chopped onions or squash or whatever needed chopping, for the soup or stew Sister Victorine would put on for lunch. In garden season, they had been out already for an hour of weeding or harvesting in the half-acre garden. If it was Saturday when many of the 23 boarders went home, the Sisters and a few orphans who were old enough to work were engaged in either laundry or cleaning, getting the school, church, and convent in shape. It was, to Sister Walburga's mind, much worse than being a farm wife. It was all of that and more.

After the physical chores, Sister Walburga took up the impossible task of teaching children who would rather be off fishing or hunting and were only there for the food. Invariably, someone asked what was for lunch as soon as the school day started, although it was always soup, stew, or sandwiches. The three "s"es. They repeatedly asked how much time remained before lunch, although they couldn't tell time, none of them, even drifting into the school late, some wandering off after they'd eaten, the day's objective complete. If only they hungered after Shakespeare, thought Walburga, after knowledge, as much as after food. You would think the Good News that Jesus was the bread of life would mean more to them in their hunger, but most of the children remained unmoved. The central tenet of the Christian faith, that consuming the transfigured Body of Christ in the Eucharist brought everlasting life, did not seem to penetrate the hearts of the Chippewa.

When things were getting to her the most, Sister Walburga would retreat to the chapel. She would light one of the candles sent from the motherhouse, breathing in the sweet scent of beeswax, and she would contemplate the marble crucifix. Hers was a faith rooted in incarnation and sacrifice, God's son sent into the world in human form to suffer rejection, persecution, even betrayal, and to die for our sins, reconciling us to the Father.

The chapel at the Tallgrass Reservation was where Sister Walburga felt safe and secure, even though it had none of the grandeur of the motherhouse church four hours south and a world away. The reservation chapel had a rough-hewn wood altar covered with a blanket woven by a Chippewa woman, thick and multi-colored, nothing like the fine flax linen woven by the Sisters back home. The Sisters of Saint Bede were known for their fine craftsmanship, and their vestments and altar cloths brought an income for the community. Father Henry and Sister Michael, however, thought it was good to draw connections where possible between the native community and the Catholic faith. The blanket, which Sister Walburga thought was more suited to a horse than an altar, was one such attempt.

Still, the chapel had a simple beauty. It was white-washed and had a single round window, clear glass, in the wall behind the sanctuary, which tended to bring in a ray of light making the incense smoke dance and glinting off the chalice and paten. Over the course of an hour, in all seasons but winter, the light would reach the oak choir stalls and then dissipate as it flooded the pews where the congregation sat on Sundays and the children for Mass during the week. In October the sky was deep blue, the light sharp and penetrating, and even the lake a jewel.

Beneath the window was a real marble crucifix, a gift from the patroness of the mission, Katherine Drexel of Philadelphia. It was because of Katherine Drexel the mission had a three-story school building to house boarding students and two large classrooms, a gymnasium with an auditorium stage, and a three-story rectory with an industrial kitchen and dining room and private living quarters for six nuns and two priests, although the current staff was only the four nuns and Father Henry. It was because of her they had electricity. The building backed onto the lake and shielded from the wind as best it could the large courtyard where the gardens were. A barn housed chickens and sometimes a cow, which provided milk and eggs.

Sister Michael and Father Henry, who agreed about most things, were not fond of the crucifix. Sister Michael felt it was too grand for the mission, and that it was hard for the Chippewa to relate to as a Christ who had suffered and died for them. Sister Walburga strongly disagreed. In a world that felt almost entirely hostile, this was her Christ, with perfect marble feet she longed to bathe in her tears, or pour oil onto and wipe away with her hair like Saint Mary of Bethany. His was a face at peace beneath his crown of thorns, with the grand exhalation of It is Finished on his lips. His body was perfect, too, even the gash carved into his side, his slightly exposed ribs, and the hollow of his stomach, his sinewy arms and lean legs. Here was the one who loved mankind so much he gave his life that all might be reconciled to God. Or not all, some. Maybe the best they could do at the mission was nudge the Chippewa toward knowledge of the world outside the reservation, and fill their bellies with real food, if not the spiritual kind. Although some Chippewa confessed a belief in Christ and were baptized, Sister Walburga was not sure she had witnessed a sincere and lasting conversion among them.

Besides escaping the farm, another perk of joining the convent was shedding the name Agatha. She had never felt like an Agatha, and over the years as her mother had called it out with ever-growing impatience and demands, she'd soured on her name entirely. With names, like everything else in the convent, one could hope but had very little say in the matter. Along with all the novices in her class, Agatha wrote three names on a sheet of paper, her preferences, to be submitted to the prioress. Like the others, Agatha searched the Lives of the Saints and obscure books for a good name. The name couldn't duplicate that of a living Sister, and there were over 600 in the monastery when she entered in 1934. Many Sisters went to the cemetery looking for names not currently in use. Agatha felt she'd hit the jackpot when she found an account of a 19th century French monastery in the Sisters' library. She wrote down the names of three of those Sisters in her best hand: "Lisette, Sophie, and Adelaide." When choosing the names, one had to be particularly conscientious of possible men's names that could be taken out of them: Bernadette, for example, could land you Sister Bernard, or Leonora, Sister Leonard. After all, most of the saints were men. By far the most important, and most nerve-wracking moment of the profession liturgy was the bestowing of the name.

During the ceremony, each Sister making solemn profession approached the prioress, who welcomed her into this new life with her name. Then she was handed a slip of paper by the attending Sister so she would know how to spell it—there had been problems with that at some point. When the prioress, Sister Mechtild, took her by the shoulders and looked lovingly in her eyes and greeted her as "Sister Walburga," Agatha was too stunned to react, her throat dry and closed. When she got back to her place, she unrolled the strip of parchment on which was written in fine calligraphy, Walburga, and she wept. Though Walburga was a prominent abbess in Germany and in the highest ranks of Benedictine saints, it was not a name, nor an identity, the new Sister Walburga, age 19, felt capable of growing into, and most of all, it had no beauty in it. When she looked her up in Lives of the Saints, she discovered Walburga was the patron saint of hydrophobia, which was ironic given young Sister Walburga's fear of water after Sarah's death.

When she arrived at her first assignment, the Tallgrass Prairie mission, she had wondered if God was mocking her. Here she was, Sister Walburga, afraid of water, in a room overlooking Willow Lake. That first summer and fall, the lapping of the lake against the shore, and the terrifying storms crashing in from the west, felt like a constant threat. But that was nothing compared to winter.

In winter, the frozen lake moaned and boomed at night. She'd had a fear of ice since Sarah's drowning, and the ongoing violence of the lake in winter, night after night, kept her awake. She had heard and expected the cracking of ice as the lake contracted, but the moaning, the pinging, sometimes animal sounds and then otherworldly vibrations, were fearsome. And then the loud booms made her think about submarines along the coast that were part of the war in Europe. Sister Michael called it the "song" of the lake; she went so far as going out and putting her head on the ice to hear it when the snow wasn't deep. You wouldn't catch Sister Walburga on Willow Lake, winter or summer.

Father Henry was young and good looking and had been raised in the Twin Cities. He had volunteered for the mission, and there was no putting him off. Although he was a city boy through and through, he enjoyed chopping wood, so he spent a great deal of his outdoor time doing exactly that. The reservation always needed split wood, and to his credit he also took on keeping the cribs by the fireplace and stoves filled so Sister Michael or Sister Victorine didn't have to do it.

Like all priests, he wore only black clothing. He had one blue cable wool sweater he'd pull out in the depths of winter, but mostly he wore black wool turtlenecks that must have itched terribly, Walburga thought, and short-sleeved black cotton shirts with a collar in summer, always over black trousers.

Father Henry's hair was brown and thick, with a natural wave where the hair lay on his forehead. His eyes were dark and piercing, and if he missed one shave his beard would make itself known. There was no question he was a handsome man, and he saw the whole endeavor as a great adventure. It was easier for priests. They were not expected to do domestic tasks and could apply themselves to spiritual matters, study, and activities like hiking, fishing, and skiing. He didn't even clean his own suite of rooms. Sister Victorine took care of that. He did, however, make his own bed, and he did that very well, military style.

He and Sister Michael often walked together along the lake sharing stories they heard from the Indians. It was a platonic relationship, as far as Sister Walburga could tell. She suspected Sister Michael had wanted to be a priest, since she so often shared the story of playing Mass at home with her siblings, herself in the role of "priest" handing out Necco Wafer hosts. Instead, Michael settled for sacristan, trimming and lighting the candles, arranging flowers in season, greenery at Advent, and even making paper Easter lilies and Christmas poinsettias since there was no way to procure live flowers in winter or spring way out there. How anyone had time for niceties like that, or for talk, Sister Walburga did not know. If she had free time, she spent it praying for deliverance from this place, focusing on the psalms which cried out from the wilderness or found one surrounded and ensnared by enemies. How she longed to rest in God, to have a balm for her cracked lips and hands that wasn't lard, to be gathered under God's warm feathers like chicks with a mother hen. But it was not to be, and every year, 1940, 1941, 1942, her assignment came back the same.

God did not deliver Sister Walburga. But in November of 1942, God did answer her prayers. God provided a beast, like he provided a ram to Abraham to sacrifice in place of Isaac. It was the hardest lesson in grace she had ever experienced, and it changed her relationship to the place forever.

In winter, there was very little meat. There was plenty of squash, potatoes, turnips, and rutabaga, and they also had a large store of chestnuts and hazelnuts they'd shell with great effort, soak, and roast. And of course, there were eggs even when the chickens slowed down their laying, enough for the Sisters and Father Henry to have one for breakfast every day, with salted pork on Sunday. The boarding children had porridge in the morning and didn't complain. It was served hot, often with a bit of maple syrup and ground hazelnuts in it.

The Sisters always had meat for Thanksgiving, a turkey or a ham. But that year everything was scarce and rationed because of the war. Sister Victorine had put aside enough sugar for a sweet potato pie, and there was talk of killing a few of the older chickens for soup.

The first bitter cold snap came early, in late October. On Wednesday night, when the lake was going through its freezing pains, and otherwise the world was bone quiet, everyone was awakened by a pounding on the door. Sister Mary Peter was in the residence with the boarding students, so it was just Sister Walburga, Sister Michael, and Sister Victorine in the convent, and Father Henry a floor below them in his suite. The pounding woke Father Henry first, and the sound of male voices roused the rest. The Sisters threw on their habits over their nightgowns and went down to find Father Henry, his face pale, talking to a group of Chippewa men.

They had brought a gift. Miigiwewin. It was hard to make out, the giant heap of fur on the doorstep surrounded by the Indians. It almost looked like a mound of dirt or, Sister Walburga at first suspected, something hidden beneath a fur rug.

"What is it?" Michael asked.

"A bear," Father Henry said.

"A what?" Michael repeated, though now it was taking shape before them.

"A bear," he said. "For Thanksgiving."

"Oh," Sister Victorine said. "Don't they know corn is traditional?" Sister Victorine could be funny that way, but no one laughed.

"They want to know where to put it," Father Henry said, turning to her.

"What? Well, I wouldn't know the first thing about what to do with it," Victorine answered, her hand to her chest.

"It's too cold to go in the barn. It will freeze by morning. What about the cellar? It will have to be the cellar," Sister Michael said.

And so Father Henry ushered the men inside. One man heaved the bear carcass onto his back, and the Sisters saw the head for the first time, the snout bent into the man's neck and flopping along his shoulder, the tongue sticking out of the side of its mouth. Two other men helped center it, and the man half-dragged it through the door. The scent of the thing, bringing with it a deep cold and yet also animal, dead animal, stronger than any deer, filled the entryway.

"Here, here," Sister Michael said, taking charge and leading them to the stairs down to the cellar. Sister Walburga watched the floor, expecting to see a trail of blood, the animal was that fresh and the scent that strong. Father Henry closed the door and followed along with Victorine. They dropped the bear on the dirt floor near the drain, and after much thanking and signs of peace, and some talk the Sisters couldn't understand, not speaking Ojibwe, and which afterward Henry thought might have been helpful instructions if only they could parse it, the Indians went on their way. Sister Victorine gathered a burlap bag of potatoes and onions for them in return for the generous gift before showing them out.

Alone with the bear, Father Henry started to laugh. "Well, this is one for the history books!" he said. "They won't believe it back at the abbey!"

"I don't know how you can laugh," said Sister Walburga. "What on earth are we going to do with it?"

"We'll have to butcher it," Sister Victorine said, "though I don't have the first idea. It certainly is not like a deer or a fish."

Those were the usual gifts, a bucket of walleye or Northern pike, a deer in season, although not yet that year. Victorine and Henry had together, with the help of books, taught themselves how to butcher a deer.

"I guess we'd better do it tonight and get the meat packed away," Henry said. "I'm going to go put on some more sensible clothes and get a sharp knife or two."

"Maybe you should bring a saw," Michael added.

While he and Victorine were putting on their butchering clothes and aprons, gathering supplies, Sister Michael examined the bear. "Help me turn it over," she said to Sister Walburga. Although she was loathe to touch the beast, Walburga was curious, and she knelt on the dirt floor and helped Sister Michael push it from its side, where it had slumped off the man's back, facing up. It was a fine specimen, a male, and the single shot had gone clear through its skull. The Indians had slit its belly and removed the entrails to lighten the load, but the rest of the bear was intact.

"How far did they bring it do you think?" Sister Walburga asked.

"They had a sled, but still," Sister Michael answered. "How on earth did that man lift it onto his back and carry it?"

"Dragged, but yes, you're right. It must be 200 pounds, don't ya think?"

"It is late in the season," Sister Michael said.

"The very end," Walburga agreed. "Didn't make it to his den before the cold."

They both took in the bear, silently. Sister Michael stroked its fur.

"I hope it isn't diseased," Walburga said.

Michael moved her hand away and stared. "Looks fine to me. The Indians would know. Right?"

"I s'pose."

Victorine and Henry returned, Victorine bringing aprons for the other Sisters. They knew they needed to hang it like a deer, and between the four of them they got the arms secured, threw the ropes over a beam, and Michael and Henry hoisted it up and tied it off.

"Doesn't look so big this way," Henry said.

The bear hung there, its shattered head down on its chest. It looked uncomfortably close to the body of a man.

"Oh dear," Victorine said and Henry, knife in hand, looked at her solemnly.

"We should pray," Michael said. Walburga wanted more than anything to go back to bed, but the others were already spreading out in a tight circle by the hoisted bear.

"Would you offer the prayer, Sister Michael?" Henry asked. It seemed impossible the man wielding the knife could do it.

Sister Michael nodded, then bowed her head along with the others. "Provider God, you who created all creatures under heaven, we thank you for this gift. For the gift of our Chippewa neighbors, who out of generosity and care for us, the strangers in their midst, knowing and honoring the coming holiday by which our peoples first came together in peace, have bestowed upon us this gift. We had no meat, and now we have meat. May we receive this offering humbly and with grace.

"And now we raise our hands to bless the bear, this Ursa Major whose constellation walks the northern sky. Heavenly Father, you have set this creature in the sky to guide our ancestors, and on earth where, though he is fearsome, he is part of the great circle of life. We are grateful for this bounteous gift, and we will remember him again when we give thanks on the great feast of Thanksgiving, and every time in this cold season we partake of his flesh. This gift of meat brings close our dependence on the bounty of your creation even as we enter the season of scarcity, and your great love for us, Father, who provides all we need. Amen."

The others joined in the Amen, and when Walburga opened her eyes, she saw that Victorine had tears running down her cheeks. For Victorine it had been the hardest, worrying about what to do for Thanksgiving and feeling the loss of the traditional ham or turkey. Still, Walburga had been praying not for a bear but for a goose or two. She did not have the faith, nor the gratitude, that seemed to come so easily to the others.

The smart move would have been to cut the hide away from the arms and work down, but Henry figured he'd go in where the Indians had already started off, and tried pulling back the skin from the ribs, cutting it away with his knife. He didn't get far before he got lost in the shoulder, and also it was clear that a good deal of fur was becoming dislodged with the hide and making its way into the carcass.

"Well, there goes my hopes for a rug," he said, letting out a tight laugh.

Walburga was sent upstairs to pump and fill buckets of water, so the carcass could be cleaned as he went along. Henry started again, this time from the arms, but it was a hack job from beginning to end. The cold water made a mess of the floor, which after two hours was littered with fur and strips of hide. By then Henry was sweating and even muttering curses, and Walburga didn't blame him. When he took the Lord's name in vain, Sister Michael would clear her throat, and he'd stop to wipe his brow and say, "Sorry, Sisters," but the next time he broke through the skin or loosened a hunk of hair into his mouth, he'd slip up again.

When the hide was completely stripped away, he used his knife to separate the white layer of fat, which Victorine kept aside for rendering. She would need to strain out quite a bit of fur, but she was happy for the rich fat, which she would use for many things, including soap.

That was the worst moment, once the flesh was exposed. Henry stepped back and they all stood in silence. The flesh of the creature, the hollowed ribs and gentle head, hung there on sinewy arms that ended with the large pads of paws, strung by ropes over the beam. No one said what they all were thinking, but Walburga could feel things getting more and more fraught. Suffering. Such savage suffering. The animal scent of the dark red meat. She stepped forward and sloshed a pail of cold water over the carcass, attempting to wash away the image in all their heads and usher them on to the next stage of butchering. It is just meat, she seemed to be saying, despite the hollowed ribs, the gashes in his side. The sinewy arms.

The saw was employed at the joints, and eventually several large roasts were cut from the beast. Sister Michael received these and wrapped them in paper for freezing. Much of the meat, however, would require grinding, as it was no more than scraps when Father Henry freed it from the bone. Once the limbs were severed, the work was moved to a large wood table, and the blood would never completely come out of it, despite Sister Victorine's scrubbing.

The entire night passed like this. Sister Walburga was called upon to fetch more water and to move the packages into cold storage until it could be transported to an old milk truck in the barn used to store meat in freezing temperatures because, ironically, it was bear-proof.

Sister Michael didn't leave to start the bread, and none of them broke for Lauds at five. The sun didn't rise until after six, by which time the carcass was completely stripped, the bear reduced to an undignified pile of fur. Even the bones, most of them, had been wrapped and put aside for broth.

"Look at it all," Sister Victorine said. "It will feed us all, all winter." It was true, a large store of meat, more than a deer. The wrapped packages, marked with a grease pencil by Victorine, filled two large baskets, with more stacked on the table.

On their way out of the cellar, Sister Walburga was last, pulling the cord on the bare lightbulb. Before she did, looking down, she saw the hem of her nightgown, peeking from her habit, was stained with blood. The cellar fell into darkness, but as the tired crew tromped up the stairs, the gray light of dawn allowed them to see their way.

In the kitchen windows, the deep red sun particular to freezing weather was rising from the lake. They all paused at the kitchen windows and this time all three Sisters, even Walburga, began to cry.

She couldn't say what it was. The savage violence committed by Father Henry's knife. Just the plain misery of wilderness. But also, despite itself, the mystery and beauty. On some level, the recognition they all would live.

Father Henry shrugged off his oilskin apron, and the Sisters removed them, heavily, from their shoulders. Sister Michael moved toward the flour bin to make biscuits. There would be no bread today. Victorine handed a bar of lye soap to Walburga, who leaned on the pump once more to fill a basin for washing. As she walked down the hallway to the shared bath, she stopped and closed her eyes, pressing them tightly to stop her tears. In that darkness she heard the song of the lake, and smelled the lye soap mingled with the blood in her cracked skin. She saw light, the flames of candles, and felt a surge of great love, a sacrificial love. The light swam before her, became the points of stars, a great bear walking across the sky.