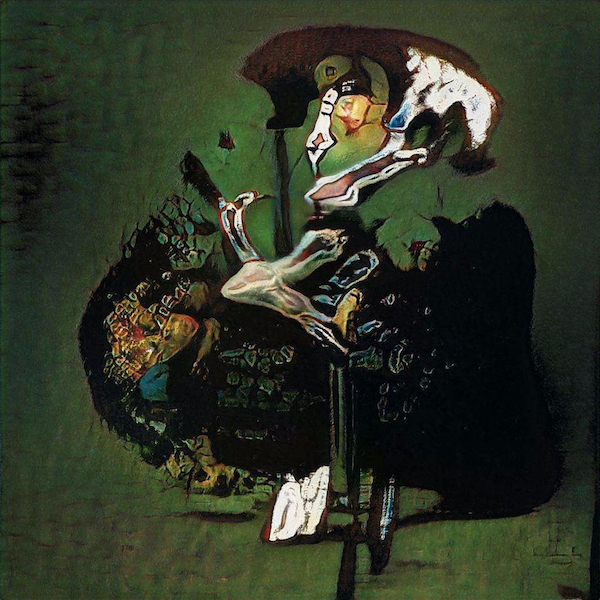

Artwork by Art AI Gallery

To the weekend warriors who flock to Kanchanaburi from the capital every weekend in droves, the province offers a refuge of clean air and open spaces. They come to party on the reservoirs, to take selfies on mountain trails standing in front of idyllic waterfalls, or maybe for a dinner cruise down the world famous River Kwai. What they don't see from the cruise boats and forest resorts is, on either side of the highway, down the rutted red-dirt roads, there are villages out in the sticks, little changed since the bronze age.

Poor places where multi-generational families live in naked block homes or ones twined up of wattle and mud. Where people still forage for wild vegetables and meals are eaten by hand. Where everyone knows each other's business, and there's little use for the law or government.

This doesn't mean kids aren't smoking crank and racing motorcycles, or that no one is fiddling with facebook on their phones, or girls aren't wearing painted-on jeans. It means the spirits, beasts and ghosts of Thai lore, are as important out here where ducks and sheep are still herded with crook and dog as they ever were. That elders are still bent at the waist like snapped reeds from the weight of a million shoots of rice planted and replanted. It means these are places where tradition isn't the past.

In one of these villages, a battle of magic played out recently. A village where the temple is the social center, and its monks are the sole defense against evil in the world. Superstition means more than science. The people believe in omens, bad juju, and the word of Buddha as it has been twisted and perverted through the teaching of holy men. Which is why it was a problem when new monks showed up.

The temple is small, housing only three monks and an old Abbott. Novices come and go with the rain season as all Thai boys are indoctrinated even if for only a few minutes, so a wandering monk is nothing exceptional. Some never settle, only move from temple to temple in a never-ending, unshod pilgrimage. Staying at a given temple for just long enough to put a little meat on their bones before wandering off again.

When the first one showed up, villagers paid no notice. He was attached to the end of the alms procession in the morning, and though he was young, there was nothing special about him. The next two who came along in the back of a new, expensive-looking pick-up truck handling three big dogs chained to the floor caused more speculation. It wasn't the season for new monks, and what kind of monks managed vicious-looking dogs?

Mae Ant lived outside the bosom of the village in a shack of cast-off materials scrounged from the fields and scrub jungle where townspeople dumped their rubbish. She was ageless in colorless workmen's polyester slacks, layers topped with a flannel shirt and giant sun bonnet—her daily uniform as she made her ponderously slow circuit of the back roads. More often shuffling forward with her ancient bicycle then pedaling it.

Mothers told children to be wary of the old woman, who was rightfully accused of being a witch. Her bicycle bedazzled with trappings of her craft old and new. Discarded CD's hung across the bars to reflect the broiling daylight, which negated the evil eye. Tassels streamed from seat and handlebars scrawled upon in a language ancient when the Budda was still a young prince. Her tires were split open, stuffed with rags, and stitched back together with twine and awl. She carted plastic bags in which to separate her findings, and a telescoping car antenna sharpened at one end to poke through piles of trash and investigate road kill without having to bend over.

Mae Ant was neither a good nor bad witch since there is no such thing. She made no distinction between black and white magic. The villagers collectively ignored her during the daytime as a hermit who had lost her mind long ago. At night, though, many made their way to her shack looking for a lucky number or a love potion or to drop a curse on a rival, and they paid her asking price.

She was born of the coupling of her witch mother and a black mountain dog whom they butchered and ate together on her fifth birthday. Her mother fed her the heart, which imbued her with a certain persuasion over the thoughts of dogs. It was clear to her when she first cast her rheumy eyes on the new monks that the temple was under control of evil, and that her old friend and combatant the abbot Pre Muchinakan was in danger.

Days after the first three monks arrived, the old abbot was replaced by a looming, dark monk with faded blue script tattooed all across his crumpled pate and even on the lids of his hard eyes. Only two monks came to the village to collect alms in the morning, consistently late, and when they did show, the ritual felt more like a shakedown than making merit.

The condition of the temple began to deteriorate almost as soon as the new monks appeared. They didn't cut the weeds and grass or rake and sweep the courtyards. The women in their disgust stayed away, but some of the men and even a few older boys were spending more time at the gilded buildings up on the hill than ever before, and they came home late and drunk. From the terrific noise and depleting population of feral canines in the village, it was simple to conclude the monks were fighting dogs behind the main stupa.

It was by matter of criminal dealings more than that. They were also running numbers and had a couple of young girls turning tricks out of their living quarters to the rare winner. This was all small beer, and aside from their main enterprise of transporting methamphetamine from the border, dealing a small amount out of the temple to keep their activities ticking over but running the bulk to a contact in the capital. It wasn't unique or anything new to have bad monks. The sanctity of the cloth attracts criminals like durian draws tigers.

One of Mae Ant's witchly occupations was to perform abortions on the few girls who didn't want their babies and occasionally a married woman who had no explanation for being pregnant to a speculative husband. She was paid for the procedure, but her own interests were different: with each abortion Mae Ant used the discarded fetal tissue to forge a very special idol.

Luk Thong idols, or golden children, were by tradition still-born fetuses dry roasted to mummification. Lacquered and gilded, the fetus would be venerated by the parents to appease the ghost of the unborn child. A practice long discouraged in the temples where it began, but Mae Ant found even a small amount of fetal tissue ash cast into Luk Krong idols did just as well to conjure the child ghosts, and so did her clients.

The old woman made her plans for the next moonless night, a black moon being good for magic. Villagers normally stay home when there is no moon for fear of the evil spirits who take advantage of absolute darkness.

Luk Krong are as precocious and self-centered as any real child and demand attention. Special foods and gifts must be offered daily to keep them happy and useful to their keepers. It was her family of Luk Krong whom Mae Ant relied on when dirty deeds were necessary, as children, real and ephemeral, love to cause mischief. So the old witch summoned two of the boys with an abundant offering of chocolate milk, cookies, and chips and tasked them with releasing the monks' stable of fighting dogs and rousing them into a fury by pulling their tales and clipping their ears.

Then she summoned two of the girls with orange soda, sweet lychees, and colorful bits and bobs and sent them to go through the monks rooms, sack the places, and report on what they might find.

When the kids were gone, she stripped down to her wrinkled birthday suit, made leathery with the blurred strings of incantations, prayers, spells, and curses tattooed around her bony body. She covered herself in a sheen of python oil, took a shot of fermented cat's piss before kneeling in front of her all-purpose big magic altar, and fell into a fit.

She had seen the monk who had taken the old abbot's position in her viewing crystal and knew just from the spells etched on the usurper's shaved head that he had a skinful of Sak Yaht: tattoos protecting him from bullets, knives, disease, snakes, and all manner of death and misdead. Just as her own would for her.

There were exceptions to the tattoos' power, though. Even the most protected were vulnerable to death when either evacuating the bowels or in the very grip of an orgasm. The witch could only get at the false monk shitting or cumming, so she decided on cumming, it having been awhile since she had a piece of ass her own self.

She shook and trembled in front of the altar, glossy in her coating of snake grease, mumbling a spell that would steal the youth of a village girl whom she had plucked a single hair from that afternoon. She rose transformed to a woman in the full bloom of her wiles. In front of the cracked mirror hanging from a bit of wire over the shack's door to protect from looking magic, she admired her high, firm breasts, tight belly and long, taut legs.

Wrapping herself in an almost clean house cloth, she tucked a giant porcupine quill soaked in viper venom in the bun of thick black hair gathered atop her head and went out into the moonless night to meet, fuck, and kill the dark monk.

On the hill path to the temple, she could see the younger monks chasing the furious dogs, who were still being tormented by her spirit boys. The Luk Krong were using catapults to snipe the dogs' balls. Boys will be boys she thought, alive or dead. Closer still she came across her girls, who carried wads of cash but looked stricken. When she stopped them to find out about the old abbot, the girls said he was locked in his room and meditating heavily, but even so he could see them and even scolded them. How Momma, they wanted to know, could the fierce man see them?

He's got his powers, she noted to no one else as she topped the brow of the hill and saw the monk centered in the temple's courtyard, lit from all sides by lawn lights meant to highlight the gold-painted Buddha sculptures surrounding them. He had cast his own youth-stealing spell and stood shirtless in fisherman's pants that hid no part of his diamond-cut torso.

They walked toward one another, and she let the thin cloth slip from her body. He stepped out of the loose-fitting trousers, and they met body to body in the light, coupling immediately. He took her around the world, no holes barred, and she him, until her haunches began to quiver and his frame tightened against the mounting eruption.

Mae Ant slipped the quill from her hair, the full length of black locks cascading around her, and jabbed it into the femoral artery in the monk's thigh as he blew his wad in her old quinny. At the same instant, the monk groaned into her ear, Now to hell, old witch, and tore the throat from the her neck with tiger's claws fixed to his own bony fingers, just as the venom froze his heart and the two collapsed in a heap of post-coital death spasm.

The underling monks departed before sun-up in their big, bad-ass truck, taking with them what drugs were left. The cash was gone, the dogs never to return. By mid morning the old abbot, released from his incarceration, summoned his three students from the temple where they had taken refuge from the criminals. They gathered the desiccated corpses of the monk and the old witch, now returned to their geriatric states, twined in a rictus of mutual sexual assault and already blistering under the glare of late-morning sun.

The monks hauled the couple to the crematorium in a wheelbarrow and burned them to ash without thought for ceremony. That night the old abbot had their sooty remains delivered to him in his cell, where he mixed them with the local umber-colored clay, which his apprentices stamped with a block of incantations he had spent the day composing, and then he cut and bisqued each of these muddy wafers into idols, gilded and blessed. The abbot was sure the amulets would fetch a high price among the Bangkok tourists once the story of the battle got around. It was just the kind of publicity that might pull an old abbot out of obscurity and into a Mercedes Benz S class coupe.