Artwork by Art AI Gallery

I came to the desert with more than I strictly needed to get the job done. I took my grandmother's sachet of lavender, a copy of the day's newspaper, the book I was reading, some beef jerky in a pack, and of course, a lighter and a jug of kerosene. I wore a purple silk robe patterned in roses and arabesques.

I got here in the passenger seat of an 18-wheeler, at least part of the way. There aren't too many drivers heading so far east in San Diego and then Imperial County, and those who do don't typically clear the Salton Sea. After hitchhiking in, I have to walk. I have to walk a long, long way. But I'm not lost; I know exactly where I'm going. I'm following the road north and then northwest as the wide, warm, shallow silver sea glitters to the left of me. Maybe it might sound grim, walking so many miles alone in the desert, but really I don't feel that way. I even catch myself whistling. It's one of the reasons I wore the robe; it makes things feel lighter. Things like horror, things like death. I used to stay up awake at night thinking of all the things another person could do to me to ruin my body and break my spirit: skin me alive, pluck out my eyes, mash my hands and feet into dead pulps.

And the worst thought... that maybe I deserved all that, or at least it would balance something out, cosmically. I mean, someone out there in history has gone through those things, probably lots of people. And if someone's had to live through it, why shouldn't I?

Now, when I start to think like that, I laugh. Not because it's funny, but because if I laugh hard enough, the thoughts go away. That's one thing I learned from being an actor. Your body doesn't know the difference. Laugh or cry long enough, and you'll feel it in your chest like it was real.

Something about the road out here—the wash that goes for miles, the sand and mountains beyond it—feels like I'm on a quest. I guess I am. And then I start thinking about riddles, and about my favorite riddle, my favorite because I can't ever quite figure out what the answer is, and every time I think it over, I have a different idea.

It goes like this. Theseus, a great Greek hero, or maybe just a young prince on a power trip who went into a labyrinth with a ball of string and killed a person, a person who had been kept alone in the dark their whole life, a person punished because their father defied the gods and their mother had sex with a white bull, a person ugly and deformed and abandoned. That Theseus. He sets sail from Crete on a quest that will change his life, and definitely the lives of others, and when he leaves, his ship is in tip-top shape. Brand new. Along the way he encounters storms, monsters, maybe a few lightning strikes from Zeus, and each time he lands on an island, he has to make repairs to the ship with what materials he can find. Years later, haggard and bearded and a decade older, he makes it back to Crete. He's unrecognizable. And his ship, the one he set out with, it's been repaired so many times now, it doesn't have a single piece remaining from the original vessel. Not the deck, or the hull, or the sails, or the masts, or anything else that makes a ship a ship.

So the question is, by the time Theseus returns, is his ship the same ship he left with? Is he the same Theseus?

If I built a ship myself out here, I could drag it out past the wash, over the cracked skeletons and buzzing flies until I got right to the edge of the putrid shore and the muddy banks littered with decaying corpses of creatures too mutated and deformed to call fish. The Salton Sea was an accident, at first a happy one, a flood in the desert when a dam burst and rerouted the Colorado River out a hundred miles past where it was meant to be. For awhile, it became a vacation spot, like an off-brand Palm Springs. People bought up property and went swimming and fishing and boating. But they didn't think. They didn't know much about seas, or rivers, or how bodies of water without a way to let go, turn into wastelands of death and salt. So the tourists fled. The luxury hotels boarded up. The fish died screaming. And yet the Sea itself is still around, drying up slowly, glinting silver in the cold light of the midwinter sun. It's strange to say, but I've always taken a kind of comfort in it. A feeling of kinship. After all, I'm a body of water, too, though I don't think of myself as the Salton Sea. I think if I could be anything, I'd be an alpine lake, something high in the Sierras, something untouched except by black bears and a backpacker here and there.

Maybe that's where I'll go next. I have to think like that, where I'll go next, what's waiting for me in my future. Because when I was younger, in more pain, I didn't think about that kind of thing at all. The age of 30 felt as foreign as Jupiter. So I think, I'm going to an alpine lake in the Sierras, and I imagine myself laying down on a thick picnic blanket (I packed that with me, too—it's good to be prepared) and staring up at the true dark-sky stars. I imagine myself picking berries (what kinds of berries grow up there? Huckleberries, I decide, and I don't even know what a huckleberry looks like) and making fir needle tea at night. Crawling on the rocks like a bear, snatching at fish with my hands.

Before I know it, I've followed my memory to the old hut.

If you've never spent much time in the American Southwest, I've got to tell you, it's unlike anywhere else in the world. Or at least, anywhere else I've seen pictures of. Out in the really rural desert, it's hard to tell deserted crackhouses from works of astonishing art, because there's plenty of both, and sometimes they're the same building. People create with the tools they've got on hand, out here; they weld and stitch and spray paint.

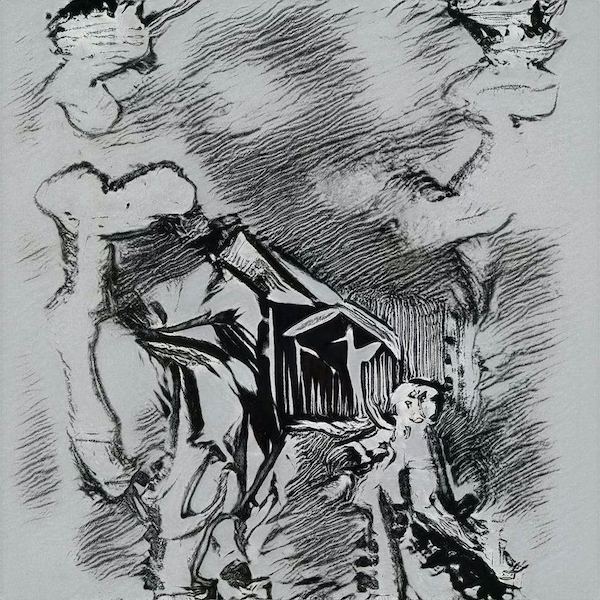

So, imagine a wooden hut on the side of the road. It's maybe bigger than whatever you're imagining, it's got two rooms and a bathroom. I don't know what it was built for, originally, maybe as some kind of directory point for the Sea's golden age of tourism. It's long since been gutted for every possible copper pipe and ceramic fixture. It's nothing but walls. And those walls are covered, truly covered, with every kind of tagging and graffiti you can picture. It's stunning, really. The most vivid is a bright blue-and-red Eye of Horus painted over the front door. It's a new addition since I was here last. An ancient Egyptian symbol of protection. How ironic.

I had told myself I wouldn't go inside. What's the use of that, I'd thought? You think picking at scabs is some kind of honorable, like you need to deep-dive your own trauma to clear it out and heal it. But the truth is the mind does most of that healing itself. What you really need is to sleep, and be kind to yourself. I've never been very kind to myself. I go inside.

It's just like I remember it. Just the same. In some way I have always been here, always will be. I try to still my hands. Acting. Acting taught me everything about how to be a person. I take a deep breath and square my shoulders and try to be someone whose horrors are an interesting fact about them and not the black hole pulling them apart. Black holes warp time as well as space. You can't get away from them any more than you can turn time around and walk into the past. And once you're in, time splits into two realities. In one, you are consumed and destroyed, but in the other, you go on more or less the same as before. That's what I read once, and if you get down to it, that's why I'm here now. If you can't escape the black hole, then the only way to go is in. And if you do, maybe it isn't certain death anymore. Maybe it's more like a portal.

But in the black hole, you're alone. Sound travels differently out there. You don't expect to hear the wind rushing through the scattered shrubs outside, or the hee-haw of some distant scrap-metal windchime. You definitely don't expect to hear snoring.

I panic. My heart turns to solid ice, and my knees lock, and I fall sideways into the corner of the wall. I stay there, half-collapsed, waiting for death, I guess, but after a few moments it passes and—I can't help myself—I move forward, silent, to the second room.

There's a stained bare mattress on the floor, a man passed out on top. I stare at him for a few long minutes, trying to arrange his features in my brain, and finally I decide I don't know him. His face is creased and sun-weathered, with a dark curly beard creeping along his jaw and down his neck. Actually, he doesn't look too much older than me, though he hasn't seen clean clothes or a shower in a long time.

I can only stand and stare. It takes him an age to wake up, but when he does, his eyes snap open and meet mine. He swears and jerks back, hits his head against the wall, fumbling for something.

"I'm sorry," I near-shout, and launch myself toward him before he can grab whatever weapon he might have been reaching for. I'm on top of him, my hands grappling at his shoulders. I have him for a second, maybe even less, before he flips me over, and his eyes are like flames in his head, and he's screaming things at me, and I go completely rigid like a corpse. I can't move. I can't speak. I can only stare into his eyes, like I'm looking in there for all the answers to my riddles, like his eyes are the singularity inside the black hole of the shack, like I've finally reached it, the point of no return.

If you're tortured inside a room, do you ever leave the room? If you enter the black hole, how do you know you'll be the self who gets to live?

"Who the fuck are you," he says, but I can't speak, and I don't know if I could answer the question anyway.

"What the fuck are you doing here," he says.

With a tremendous effort, I open my mouth and croak out some sounds I don't recognize. A sudden strange calm comes over me. In the labyrinth, the monster is the hero and the hero is the monster. If this is the singularity, if time only goes forward, if gravity keeps me on the earth, if I have always been inside this room, then there's only one direction I could ever have gone in.

"I'm here," is all I can say.

He gets his face right up to mine, snarls and bares his teeth. "This is some shit," he says. Then he lets go of me. He leans back. "I could kill you," he says.

"You could torture me," I say, giving him my worst fear, the most dangerous weapon, just like that. It's a relief to say it out loud. "You could tie me up and rip me apart."

"Yeah," he says, but something in his voice wavers.

"You could skin me alive or cut my fingers off," I say. "Or pull out my eyes."

"All right, fuck, stop it," he says, and he flinches. "Just stop. What the fuck is wrong with you?"

I realize something then. He doesn't want to hurt me. Whether he likes it or not, he is too much like me. He has skin and eyes and fingers of his own.

I said before, I'm afraid of pain, real pain, the kind that can make you into something else. Something less than human. But I don't think you need to be tortured to be mutilated. There's a lot of less messy ways to do that to a person, a lot of ways to get in someone's head and make them unrecognizable. Make them a person who wouldn't flinch.

"What are you doing here?" he asks again, but in a calmer voice this time.

"I was here a long time ago," I say, and I know it isn't an answer. "I need to do something."

"Fuck," he says with feeling, and puts a hand to his head. "I'm so hungover, and I've been having weird fucking dreams. Okay."

He reaches for something beside the bed, and I tense to bolt, but it isn't a weapon. It's a can of spray paint. I guess, in a pinch, it could be a kind of weapon, but it doesn't look like he's planning to use it on me.

"I'm passing through, all right?" he says. "Only been here two nights. Painting my way through the county. You an artist?"

"Kind of."

He hauls himself to his feet. He's taller than me. "So what did you come here to do, then?"

I'm quiet for a moment. I could lie, I think. But I don't.

"I want to burn it down," I say.

His eyebrows raise a little, but then he smiles wide. He's missing a few teeth in front, and it makes him look fierce, like a pirate. He looks out the empty window.

"Full moon tonight," he says. "I was going to head out anyway. I'll help you."

So that's how it happens. He takes his time spreading out the newspaper, really getting into all the corners. He knows what he's doing, balling up the paper and making thick layers in places where the wooden planks are likely to catch best. Then I drench the walls in kerosene, to speed things up.

I keep one ball of newspaper for myself, and we go outside to survey our work.

"Are you the one who did all this painting?" I ask him.

He shrugs. "Some of it, but not all. Lots of artists and taggers coming through here. You know enough about the signatures, you can trace a lot of history through paint jobs like this. You see where people tagged on top of other tags, you see where a tag's been left up for months or years out of respect. It tells you a lot about who's coming through here, what they're thinking about, what their story is."

I think about that, let the signatures and the colors and the vivid Eye of Horus fill up my own eyes for a long moment, before I flick my lighter on the ball of newspaper and throw it into the hut.

And the world, the smallest world, the labyrinth and the black hole all in one, goes up in a blaze brighter than anything I've ever seen in my life. Brighter than fireworks, brighter than the cold winter sun. I tell myself, this is what I will take and hold inside of me, a pillar of flames in my heart, unquenchable, warmer than sunshine. It leaps and sparks in every color I can imagine. It eats the wood and the paint and the air.

The black hole reverses time, turns it around on itself. Theseus's ship returns to a port it never left. The monster in the maze, bleeding from the heart, finds its way into the light.

The hut is old, and small, and it burns quick. We retreat 20 feet back or so and sit cross-legged in the sand, just watching it, as the roaring flames settle to glowing red coals and then to gray ash. I can just make out the edge of the blackened mattress buried under charcoal planks and dust.

"Well, that's done," says the man, standing up and dusting off his palms on his pant legs. "Gotta be off, now."

"Where are you going?" I ask.

"Heading south," he says. "I have a buddy who's gonna let me stay with him down in Tijuana. Just gotta get there. Wouldn't mind company, if you want to come along."

But I'm already walking backwards, waving at him, going north.

"No," I say. "'I'm going to the Sierras."

And he shakes his head and laughs, holds up a hand to me, and turns away. I look up at the sky. The moon is brighter on this side of the black hole. I can almost see a ridge of mountains in the far northern distance, though I'm pretty sure I'm imagining them.