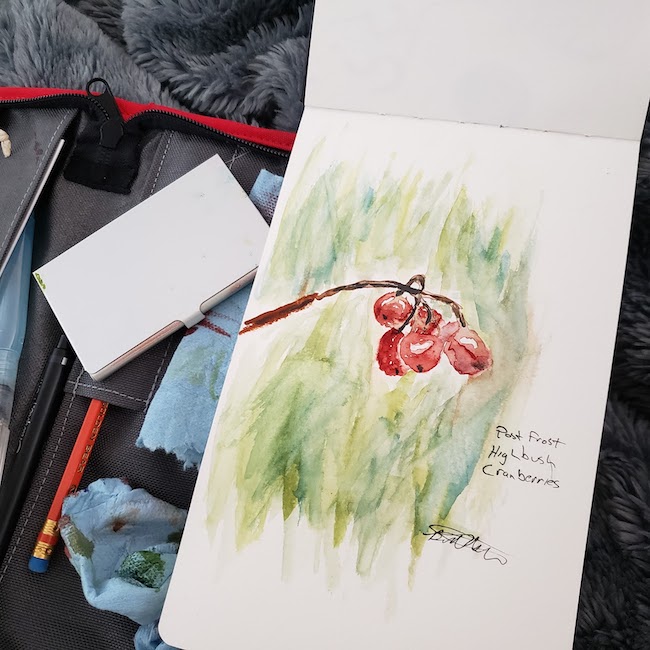

Artwork and photo by Baird Stiefel

Bound in chains to the mud, he saw above himself an exquisitely wrinkled and faintly perfumed button set between golden mounds covered in soft heather; low-hanging fruit sloping with logarithmic precision and lust-filled essence, it hovered inches above Sisyphus' agonized face. Her honeyed cheeks pulled away every time he flicked his tongue to taste her.

—The Erotic Tortures of Sisyphus, Olympia Press, 1956

What [the books of Kilgore] Trout had in common with pornography wasn't sex but fantasies of an impossibly hospitable world.

—Kurt Vonnegut

FIRST THINGS

Almost 30 years ago I made some movies with my friend, Jack Highland. By the time I realized the world saw something special in those films, I was already settled into the life of a (somewhat) respectable family man. But I never left the life I had with Jack all the way behind. Some middle-aged guys have a shameful computer folder full of carefully hidden, down-loaded porn; I have a shameful folder full of unfinished screenplays and half-finished novels. I balance my regret that the world missed out on my talent with the surety there wasn't much of it and that whatever genius there is in the films I was a part of belongs exclusively to Jack Highland. I was a sounding board, his best friend (I hope), and an extra pair of hands and eyes he could always count on. The joy with him wasn't just making movies, it was making anything. I don't know how many late-night, drunken conversations I've had with friends both before and after Jack, about all the great plans and ideas we had—each and every one of them forgotten or discarded by the next day. But with Jack, you actually did things. You followed through. You made something. And it felt so goddamn good to finish what you had started.

It's difficult to compare Jack's films to any others. To judge them based on criteria of directorial talent, cinematography, or even the individual actor performances, they hold their own with the masters of cinema. Obviously what sets Jack's films apart is the inclusion of graphic sex. If it weren't for those scenes, I think he'd be acknowledged on the same level as Kubrick, Fellini, or Mallick. But part of Jack's genius is you can't set those scenes aside. I was there for their creation; I know their origins and the intent behind them as well as anyone can, and Jack's movies couldn't exist as anything but pornography. Without sex, they just wouldn't be the films he wanted.

The question one could ask is, can a film built around various arrangements of people blowing and vigorously fucking each other be considered a "serious" film? To put it another way—does the depiction of graphic sex reduce an otherwise masterful film? Other directors have tried to dance around that line. Consider Lars Van Triers with Nymphomaniac or Vincent Gallo with The Brown Bunny. But in the end, those movies were conventional films that featured explicit sex. There's a difference in Jack's films I think it's important to emphasize. They aren't art films, they aren't mainstream, they're not genre pictures. They're porn. And anyone watching his work is uncomfortably aware they're watching a dirty movie. Jack broke the puritan heart of American film. And without violence, he walked into forbidden cinematic lands simply because he wanted to. Because it felt right.

But still... still the question. Why porn? Answer: because Jack was lonely. He was a genius, and that genius set a wall between him and the rest of the world. But also, Jack was fat and ugly. I don't say that to be cruel. I'm saying what Jack would be the first to tell you. Upon meeting any stranger, Jack had an obsessive need to make fun of himself. Jokes about his weight, or his teenage acne that hung around into his 20s, or his glasses, or his general awkwardness. He just wanted women... to be around them. He had no use for men unless, like me, they helped his art in some way. His constant focus was on the women in his life and the crippling anxiety he felt for them because they had to deal with his (as he put it) lumbering, pathetic self. If Jack was a genius filmmaker, he also had a genius for self-hatred I've never seen equaled. He was convinced he horrified every woman he ever met, and his efforts to over-correct for that sense of self-loathing made him stiff and erratic. He tried to deflect all the criticism he imagined must be racing through the other person's head by narrating his own self-criticism, simultaneously pointing out and commenting on any social misstep he committed or thought he committed as it happened. It was as exhausting to be around him sometimes as I'm sure it was to be him. One of his favorite quotes came from Kafka: "How do you accuse the man who insists on confessing?" That was Jack.

He could have made great films of any kind, but as simple as it may seem, he chose to make pornography so he could be around all the pretty girls he wanted. When he was on set, he got to be the person he wished he could. He was so, so good on set. He had a kindness that encouraged the cast and crew to give him more than they thought they could. But in the end what he loved the most were the hours and hours of talking to the beautiful, barely-clothed women who populated his films. For those precious hours he felt less like the fat, lonely, weirdo he believed he was. That doesn't undercut his sincere artistic intent. The films, in fact, are a true and radical expression of loneliness and the need for forgiveness he felt at every moment of his life.

Before writing this essay, I took a drive out to south Nashville. Jack's mom still lives there on Atkins Avenue in the house he grew up in. I never met his dad, who left when he was young, and he never talked about him other than to mention he was a former preacher who became a police detective. Jack had every teenage boy's dream: a secluded bedroom in the basement with its own bathroom and separate entrance, accessed by walking down a steep drive around to the back of the house to a wooden door with a small dirty pane of glass in it. That door led to an entrance hall which led to two more doors. The one on the left was Jack's bedroom with shelves full of fantasy and horror novels and carefully painted monster models. The door on the right led to the garage, which at one point had been used for storage until Jack lugged all that up to the attic to clear the space and use it as his first studio. When I started hanging out with him, he was already making 8mm shorts on a camera he got second hand from his uncle.

We met in an English class in the 11th grade, and he must have recognized a kindred spirit because he asked me over to his house the second week of classes and let me into his room/workspace. There were no windows to the outside, and he kept the room dark except for a directional lamp clamped to a workbench he installed to his far wall. The first day I walked in, I saw the beginnings of a small werewolf mask spread across the bench. He was in the middle of making a film featuring the mask, and he wanted my input on the design. I couldn't figure out why the mask was so small until Jack explained his story was about a young boy around eight who wears a wolf-man mask his mom bought him for Halloween. The purchase is a sacrificial act since the boy's dad hates Halloween and beats the mom in a drunken rage for wasting money. The full moon shines on the mask that night and turns the boy into an actual werewolf, allowing him to take vengeance on his father.

What was important to the 15-year-old me was not that this was a great idea for a movie (which I thought it was and still do), what mattered was the realization I could help make things, too, right now, not later, not when I grew up, but right then. Jack handed me a baggie full of hair he had collected from his dog and a jar of glue and put me to work on the mask while he cut up some plastic vampire teeth so he could glue them in the mouth. It's still one of the best days of my life.

One more memory before moving on. One day we walked to his house after school. I'd been coming over every day for weeks at this point. We'd finished the werewolf movie and were working on the next one. A rotted tree had fallen behind his house, and Jack had the idea that it had been cursed by druids and when the main character (played by my dad) uses a branch from it to fashion an ax handle, the curse turns him into an ax-murderer.

Jack was acting weird that day. He glanced back into the hallway while he shut the door to his room as if he suspected we were followed, then reached under his bed and pulled out a battered shoe box and placed it carefully on his desk. Jack had never mentioned drugs before, and for two high schoolers in the late 70s we kept remarkably clean, mostly because we were busy learning to make movies. He pulled the lid off the box, and instead of weed, inside was a jumble of tiny, plastic weapons. Laser pistols, jet packs, missiles, binoculars, swords, machine-guns, and flame-throwers from every action figure he'd ever owned. Over time he lost the figures but kept these miniature mementos. He dug his hand into the box, grabbed a handful, and let them run through his fingers like plasticized sand. He sifted his fingers through their soft edges with a lover's regret. And whatever mysterious affection he felt for those weaponized talismans made its way into the script that became The Novelty Shop.

THE NOVELTY SHOP (1981)

I assume if you're reading this essay, you know the basic outline of Novelty. The hero—a fatherless, high-school loser named Sam Black—is based on Jack. Our script weaved together several threads of his thought and is a great example of the way he drifted between ideas, making connections and finding echoes in what others mistook for chaos. He had a love for mail-order novelty ads in the back of 70's comics. When he was 12, he had actually ordered some x-ray glasses that promised to reveal the mysteries hidden under girl's clothes. They didn't work, but he still had them tucked away in his desk at home years later when we started writing Novelty. He'd take them out and set them next to his typewriter while we wrote. They became the "what if" of our script. What if, when a kid like him ordered those glasses, what came in the mail worked exactly as promised?

Even with all of Jack's savings from his various part-time jobs and the cash I was able to scrape together waiting tables, we had very little money with which to shoot. We were crashing together in a shitty apartment in South Nashville by that time and pooled our resources together for essentially everything, including making films. The idea of looking for investors never really occurred to us then. We didn't have parents or extended family with any serious money, so we started with the assumption it would be all on us. The camera, a Bolex 16mm, was a rental from a local shop, along with a Nagra recorder and a boom mike.

We tried hard to limit the number of settings and characters in the script. It gives a sparseness to Novelty, a unity in place and action. In '78, Eric Rohmer filmed an adaptation of the Perceval story with production intentionally stylized to resemble a theater stage more than a film set. I have no idea if Jack had seen that movie before we started filming, but when I compared them, I was struck by the similarity in technique. In fact, other than his garage, which served as classroom, magician's shop, and business office for the novelty company warehouse, the only other locations we used were exterior shots of a local high school, a storefront (with a hand-painted sign Jack and I made the night before stuck in the window), and an abandoned industrial building downtown as the exterior of Horror House Novelties Company.

For me, the biggest challenge when we wrote the script was the classroom scene; I couldn't see how Jack expected two 20-something, socially-awkward nobodies to persuade multiple women to come to his mother's tiny garage full of rented film equipment, disrobe, and allow us to film them for the scene where Sam tests the power of his x-ray glasses during homeroom; but Jack never seemed concerned about it. The largest expense turned out to be all the desks and chairs we needed to create a passable classroom. We filmed Jack in closeup first, sticking him in a rear corner of the class, which allowed more shots that didn't include other students. When the day finally came, Jack set up his bedroom as a dressing area. He'd sent me to Walmart the night before to buy bathrobes and snacks for the cast and crew. This scene was the only large cast day required in the film, so we wanted to be as prepared as we could. Jack had pulled together a group of 13 men and women, some college students who worked with him at the hotel and some from a local acting group, all willing to show skin in his movie for an acting credit.

At first, we filmed the scene with everyone clothed, shooting as many angles as we could imagine, maximizing our coverage. Midday we took a break, and the girls went into Jack's bedroom and stripped down to their underwear (we never address why the glasses only work to remove the outer layer of clothes, they just did, and that's how the comic ads sold them). The guys just took everything off by their desks, kicking clothes off to the side of the set. The novelty and excitement of filming that morning had worn off, and an uneasy atmosphere set in. I think they realized, even if only darkly, that exposing yourself to the camera took a willingness to be vulnerable. The actors paced around the set in their robes while we prepared to shoot the same scenes again but this time from Sam's point of view as he wore the x-ray specs. Jack seemed like an old pro, racing around to rearrange lights with our grip, Rob Becker, who along with our sound technician, Tom Campbell, and myself, made our whole crew. Even though I'm not in the movie, I had my own performance that day convincing everyone around me I knew what I was doing (I didn't) and that being in a room full of semi-nude women was no big deal to me (it was). I wasn't exactly knocking it out of the park with the ladies at that time in my life (or ever) and the proximity of so many girls in their under-clothes required effort in keeping my inner creep in check.

Now is as good a time as any to make clear that when I was writing The Novelty Shop with Jack, I had no fucking clue we were making a pornographic movie. I didn't know because Jack never told me until the moment before the sex happened. The script we wrote together did not include any sex scenes, graphic or otherwise, the scantily clad classmates were as far as it went. The classroom scene I just described ended in the script with Sam getting detention for disrupting class and then cut to him leaving the school late in the afternoon once detention was over. The sex scene with his seductive teacher during detention was written by Jack alone. The teacher was played by a woman named Tracy Demar. She was 35 when we filmed Novelty, almost 15 years older than every other actor or crew member, and she was painfully beautiful, something I realized as she stood by the chalkboard teaching class in lingerie and high heels. She was also kind and funny and a talented actress. The fact that she only ever acted in this movie is a shame—she deserved more roles. I met her that first day of filming, and on the next—I helped film her first sex scene. Somehow, between lunch and dinner on Saturday, I became an honest-to-god pornographer.

The detention scene is the only pornographic one in the entire 74 minutes of the film. The later movies have more sex in them, but for me, they don't have the power of that one scene in Novelty. Its isolation leaves you wanting more, and the chemistry between Jack and Tracy on-screen is voltaic. Jack made the decision to cut out all sound except for the ones made by their bodies. No cheesy synth. No dubbed moans. Just a microphone pushed in as tight as the camera. You can actually hear the sound of his hand groping at her back, slipping on her sweat, and the rhythmic tattoo of their bodies. For five minutes there are no cuts, no camera movement... just the rhythm of their being together.

THE ENCHIRIDION (1982)

Jack was deep into the editing process for The Novelty Shop, renting time on a moviola owned by a local college's film department and spending every possible moment assembling his film. Every few days he'd invite me to the small, campus screening room to see his progress. I'd give him my notes, which he sometimes used and sometimes ignored. Jack put the finishing touches on Novelty Shop during the day, while I kept waiting tables, and at night we'd sit in Jack's room and write the script that became The Enchiridion.

This time I had the advantage of knowing from the beginning exactly what kind of film we were making. First, we agreed that not only would the sex scenes feel natural but that they would be absolutely necessary to the plot. We wanted a story that couldn't be told without explicit sex. And not in the four-teenage-boys-losing-their-virginity kind of necessary and not the college-girls-need-money-so-bad-they-flash-their-tits kind of way. Both of those stories had been told with every degree of eroticism from soft (Porky's, Lemon Popsicle) to hard (Debbie Does Dallas, Mona the Virgin Nymph).

Jack had two movies in mind as precursors of the film we wanted to make. First, he was a huge fan of Simon, King of the Witches, a movie from the early-70s hard to describe in any satisfying way. Somehow the most applicable adjective for the movie is "nerdy." It's so grounded in the actual practice of ceremonial magic, you get the feeling the screenwriter was a lonely and disappointed loser who imagined a world where his sex-magic fantasies were real. It has sex and nudity, but unlike many movies, the sex is actually crucial to the plot, including a scene where Simon has his young, teenage gigolo/friend masturbate into a tin can for a magical rite Simon plans to perform inside the storm drain Simon used as his home. Yeah. But we loved it. The tag line from the poster really says it all: "The Black Mass... The Spells... The Incantations... The Curses... The Ceremonial Sex..."

The other film on Jack's mind at the time was Behind the Green Door. Part of that may have been a Marilyn Chambers obsession we both nurtured, but we also looked at the plot and tone of the film as something to be emulated. It was an American pornographic film, but it felt dark and surreal to us in a way suggesting Old World Europe as we imagined it, full of esoteric sex societies that ran the world during the week and fucked like crazy in palatial chateaus on the weekend. We wanted to capture the power of the diabolical ritual involved. In fact, Jack took the idea of the green door literally, turning it, in The Enchiridion, into a dark portal leading to chaotic dimensions of savage sexuality.

We started the film in the main character's small, cluttered office, surrounded by his work, trapped on all sides by chalkboards covered in symbols that could either be high-level mathematics or high-level black magic. Jack loved that it was hard to distinguish between the markings of the two. For the uninitiated it was almost impossible to differentiate between a 15th-century grimoire and a 20th-century text of theoretical mathematics. Which is why we wrote our hero, Hiram Alcanter, whose name has Kabbalistic and alchemical connotations, as a mathematics professor.

Jack was meticulous in creating the fictional "Enchiridion" book featured in the movie, spending a significant portion of his available funds. He conceived the book as a Lovecraftian Kama Sutra, and it describes sexual positions so powerful, performing them correctly can open paths to other, lust-filled dimensions. We were nothing if not thorough in our research regarding ritual and sexual magic. In a time before the Internet and online ordering and chat rooms, we gathered an impressive collection of occult books, with an emphasis on eastern tantric practice, the works of A. E. Waite and particularly the self-published memoirs of the modern magician C.F. Russell, titled Znus is Znees. What starts as a fairly straightforward life account, devolves into cryptic glyphs and sentences composed almost entirely of bizarre calculations. The result of our effort were occult designs and yogic positions in the film that are as detailed and meticulous as one can get in the field of sexual magic.

The few criticisms of The Enchiridion I've seen involve the aesthetics of the book Hiram finds on a remote stack in the university library, just before getting a blowjob from the gorgeous librarian who helps him find it (played by another wonderful actress with the screen name Charisma Strokes). The Reddit threads dedicated to Jack's movies are filled with complaints that our Enchiridion looks too new and too contemporary to be the book of sinister, eldritch power portrayed in the film. What they don't understand is that it looked exactly like Jack planned it. From the beginning he wanted it to look unassuming and academic.

In the film, the book's full title is "The Enchiridion of the Scholomance," and we imagined it as a doctoral thesis, written just after WWII by an eccentric anthropology student, a veteran who became obsessed with German occultism during the war. Unfortunately, we had to cut most of that from the final script, a victim of schedule and funding. But the book's design flowed from that backstory.

Once the illustrations and interior copy were printed, under Jack's detailed supervision, he sent them to be bound by a company that specialized in academic book-binding. He selected a black cover without any embossing, not even the title, though he made sure to include a shot of the title page to bring in some of the backstory. The illustrations of sex-positions he created have a cold, clinical look meant to contrast with the funeral-pyre knowledge they transmit. Jack hated the tradition that the ancient past had a lock on books of power, as if that power dried up just because the book had been printed in the last 50 years. And certainly, before The Enchiridion, no book like it in a movie would have been written on the sunny, scientific shores of America. He intended to subvert those tropes, but his ideas have been misinterpreted as low budget compromises. A mistake I'm glad to have the opportunity to clear up.

My favorite scene of The Enchiridion has always been the occult bookshop orgy. It was a challenge for Jack to shoot, featuring the most actors he had worked with at one time. It was a learning experience for him—keeping egos and insecurities in check, often at the same time. The scene depicts a magic working orchestrated by Hiram to break through and out of this dimension. But what makes it my personal favorite are my memories of the time spent on location preparing for the scene. We found an abandoned storefront in a crumbling strip mall on Dickerson Road, then and now the boulevard of choice for drug and prostitution transactions taking place in Nashville on any given night. We painted everything black, including the bookshelves we built to line the walls and create claustrophobic aisles. To complete the illusion of a thriving occult bookstore, Jack and I moved in our combined personal libraries and added in some of the crew's books. We finished the store off with as many gothic-themed props we could find to jam the shelves and line the area behind the counter. Jack decided on the name "Dante's" for the shop, and we placed a small placard in the front window which read: "Open midnight to sunrise." Movie-set or not, it was the kind of world Jack and I dreamed of living in, and we spent most of our free time during the shoot hanging out there. After we wrapped, Jack rented the store for a couple of additional months, like our own personal clubhouse.

MOLLY SAYS YES (1988)

Molly was changed by a fundamental shift of technology in the world of pornography, specifically the rise of VHS. The adult theaters were shutting down, and the new money was in video cassettes sales. Jack resisted the switch; he was devoted to film, but he understood by the time he made Molly that the old ways were over. Because this would be his first time using a new medium, he decided to film a smaller story than his prior films. It would take place over one day, the last day of the world, in one studio apartment, and would only have three characters: James, Molly, and the handsome Stranger in the Hall.

The apartment where we filmed Molly belonged to an actress named Madeline Woods, credited in Molly Says Yes as Lace Woods. But to me, she was always Maddie. Sweetest Maddie. We filmed in her apartment since Jack had just moved in with her. And she had changed him. Whatever insecurities Jack was working out through his art, whatever pain he was processing, she fixed it. Jack never made another movie after Molly, and that was because he had Maddie. He just didn't need to anymore. His dislike of VHS just made the decision easier.

The film was an experiment in a new format, and as far as Jack was concerned, it was not successful, even though anyone who's seen Molly Says Yes knows it's a masterpiece of minimalist pornography. I was privileged to be there when it was made. I helped with anything that was needed but contributed very little creatively on this film. It belonged to Maddie and Jack. I was barely there. The script was only a few pages long and nothing more than a sketch of the incredible footage Jack produced in those three days of filming. Except for critical passages, the dialogue was improvised, and the actors worked with a framework of markers leading to key plot points but were free to develop them in their own ways. Jack wrote the script in one night, locking himself in his bedroom while I sat in the living room, drank some whiskey, listened to some records and smoked some cigarettes. He didn't want or need my help; his creativity had outgrown mine, I guess. When he finished in the early morning, there were only 15 pages laying out three set pieces: a restrained triptych that gave away very little of the world ending outside the apartment. I was surprised when Jack decided to take a role in Molly. It had been years since he'd worked in front of the camera, but I think it was for Maddie. I think he wanted to be with her for the whole world to see.

I have a favorite passage in Molly I point to when someone questions Jack's genius. In the third act, with the destruction of the world imminent from the wandering comet crashing into it, Molly says good-bye to her husband, James, and the Stranger before they end their lives in an orgiastic denouement. Her soliloquy, some of the only scripted lines, was his best work:

Note from the editors: The legal representative of Jack Highland denied our request for permission to quote an extract from Molly Says Yes. This request was denied with the following explanation, which we have decided to include here because it is indicative of Mr. Highland's aesthetic theory.

From: The Law Offices of Molloy and Lefleur

Re: Proposed excerpt from the intellectual property—Molly Says Yes

To Whom It May Concern,

We are in receipt of your request to utilize an excerpt from the above-referenced film in an introductory essay to your anticipated collection of Mr. Highland's films. This letter is to advise you that Mr. Highland has personally rejected your request in this matter. He further wished us to relay his reasoning to you, in hopes you will understand his denial is made even though he holds Mr. Hindman in the greatest regard and is immensely flattered by your intention to issue a collection of his works. Mr. Highland believes that any strength his films possess comes from their existence as a film artifact. To present them in any other way, including a written excerpt, would diminish and misrepresent his artistic intent. Mr. Highland also wishes to remind Mr. Hindman, that this is the exact reason the original scripts for this and every other film Mr. Highland directed were burned after shooting completed. It was his intent they should only ever exist as a film object.

Just before they filmed this scene, Maddie had an attack of stage fright. She absolutely froze in front of the camera. I think she knew the power of what Jack had written for her and the responsibility of bringing it to life was a heavy burden for an inexperienced actress. I have no idea what Jack said to her when he walked over from his place behind the camera. They stood in front of a window we had lit for the scene. It had a light-box rigged outside it, simulating a world on fire, so all I could see was his silhouette leaning in close to whisper to her. They stood that way for several minutes, and then Jack walked back to the camera and called for quiet. Maddie stared after him for a few moments with a tender smile on her face, smoothed back her hair, wiped the tears from her eyes, found her mark, and gave a performance that awes me every time I watch it.

I wasn't really sure how to end this essay, and for a while it just sort of trailed off, like my friendship with Jack. There was no drama, no conflict, no hurt feelings. Jack didn't stop working, but he did stop releasing work. He stopped using crews and sets. Or scripts. And without all that baggage, he just didn't need me anymore. He and Maddie became self-contained and self-sustaining.

But then I received a postcard. From Jack. It showed a cartoon drawing of a library. A blond librarian in a short skirt, tops of her stockings clearly visible, stands on a ladder pulling a book from a shelf. Standing directly below her, a red-faced man looks up with saucer-plate eyes. The caption reads—"What did you want to look up, sir?" On the reverse, besides my name and address, was a short note written in Jack's tiny, nearly illegible script:

Chad—

It's been too long, my friend. I'm sorry I haven't tried harder to connect with you these past few years. I've been keeping busy with Maddie. We got a little place out in the sticks, you'd probably call it. It's quiet and surrounded by trees. Our nearest neighbor has a little artificial pond, no more than a couple of hundred feet across and mostly for his cows, but he lets us visit whenever we like. He built a small dock that sits out over the water. It's nice in the fall. Although I did step in cow shit one day. My foot sank in up to the ankle. It was not pleasant.

I'm running short of space. I'm writing to you to ask you to not encourage any release of my movies. I've moved on. I worry you're making them more than they were (are). I am thankful for the time we all spent making them, but I really am asking you to let them be lovely memories and nothing more.