Adam and I arrived to find the mailbox frozen shut, the road coated with ice. It dripped from the trees and caressed the rocks, as fragile as lace but treacherous. The house was hidden from view by a steep hill, buried in snow so there was no way of knowing a driveway existed except for the "No Trespassing" signs that only served to attract the attention of vandals.

"Are you sure Grandpa is here?" Adam wondered.

There were no footsteps in the snow, no tire marks, no cigar bands. Maybe he had given up smoking, but didn't he visit the neighbors to gossip? Didn't he drive into town to shop? What if he were sprawled out dead on the porch? How would anyone know?

"Give me a minute to think."

"He's not here."

"He is so."

"How do you know?"

"He's lived here ever since Grandma died."

I had stopped the car at the foot of the hill and could do nothing more than stare blankly ahead. It had been a lousy drive up in Mimi's Toyota with the heater on the blink, and words had to crack through my frozen lips.

"If he had moved, he would have let me know."

"There isn't a sign of life," Adam announced.

"I'm still his son, for crying out loud."

"A lousy one, if you want my opinion.

"I remember when he bought this place."

"Hello!" Adam howled, but there wasn't an echo.

I remembered this hill with its twists and turns and trees popping out of every crevice. I had been dreaming about crashing off cliffs ever since finagling myself into this trip.

"Hello! Grandpa? Anybody home?"

"I helped him fix the roof."

The driveway was perilously steep, and the view as you ascended was dizzying. It was narrow and unmarked so you could easily take a dive off the edge; unpaved so your back wheels created a flurry of gravel, especially if, as my father used to, you raced up and down at manic speed. In the winter, iced and slippery, the going would have been even rougher, and there was no way Mimi's car could have made it.

"It's like landing on the moon," Adam sighed.

She was forever having it repaired and sending me the bills, which I never paid, but still the damned thing took ages to start and threatened to stall and sputtered and spit in response to my touch. Just like Adam.

"My parents used to spend summers here. Then he moved here permanently."

Adam did not respond. Mimi says she was awarded the car in the divorce because I would have cracked it up anyway. Then she complains I do not visit the kid, but she can't understand I have to take the subway home, and on Sunday nights, too, when the trains hardly run. For years, Mimi had refused to lend me the car because, the last time she did, it got towed away. Which wasn't my fault.

"There isn't a sound," Adam whispered.

I admit I am a lousy driver, mainly because my father taught me up here, barking instructions into my ear so that a rare trip like this always left an ache in my shoulder blades and was always preceded by dreams about crashing off cliffs.

"Are you really sure this is the place?" he asked.

"Do you really think I would lie to you?"

But I was doing it for the kid, and Mimi was getting a Christmas vacation out of it since that's what her analyst said she needed.

"Mom says your lies are a sign of your insecurities."

"I am the most secure dude you ever met."

Which was not exactly true. What was true was that my father had no phone, so there was no way of calling, and he had not answered my letter telling him we were coming. It was highly conceivable I would have had to take Adam back to the city with my tail between my legs because I would have failed to have finagled the money he needed out of my father.

"He left the cemetery, packed a suitcase, moved up here without a word. That was two years ago."

Adam was waiting for me to outline a plan of action, as I was waiting for him. He was only 13, but he attacked the world with such bravado, he frightened Mimi, who called at midnight, crying.

"Didn't mourn for his own wife. Didn't say goodbye to me."

"Maybe he went bananas when Grandma died. Why didn't you help him out?"

"Who?"

"Grandpa."

"Maybe he always was."

"What?"

"Bananas."

"Must you always put him down?"

"You said it. I didn't."

"I said maybe he went, not maybe he always was. If you went bananas in your old age and moved to the top of a hill, so I didn't know if you were dead or alive, I'd pay you a visit and check it out. You'd still be my lousy father!"

I was, in fact, a lousier father than I was a driver. I had no patience. I did not visit. I hated him as much as I loved him but never talked things out like Mimi's analyst said I should. We had spent the entire trip up in silence. For a while, I had thought he was sleeping but had dared not turned to look. I was either too careful a driver and my father used to say that it was the frightened ones who caused all the crashes or I allowed my glance to wander at exactly the wrong moment which used to infuriate Mimi.

"Well, I'm here now," I finally muttered, not adding that my bladder was full, my head throbbing, and there was no way I could tackle my father's hill in Mimi's lemon of a car.

"Two years after Grandma died. To get your hands on some money."

"The money is for you, not me."

"You blame everything on somebody else."

Adam was short for his age but feisty like me, and I could not help admiring how he hopped from the car and surveyed the scene with authority.

"And did I tell you about the telephone?" I shouted. "He had some question about the bill and refused to pay and threatened to sue, so the company disconnected. What does that say about him, living up here without a phone?"

"It says he's got the balls to take on the phone company, which is more than I can say about you."

I remained in the car, frozen and confused, while Adam went to check out the hill. What if my father had not received my letter? Would he holler and make us return to the city, humiliating me in front of my son? What if he were shacked up with some local bimbo? How would Adam react to that?

"We'll never make it in this fucking junk heap," Adam came back to report.

"It's your mother's car, not mine. Don't blame me for the fucking car."

"It's your fucking father."

"It's you who failed French."

"I didn't fail. I got suspended."

"A failure is a failure. It's time you faced it."

If I admired him so much and he went to such lengths to imitate me, why did we attack like clattering machine guns every time we met?

"We could leave the car and walk," I suggested.

"We'd never make it alive!"

"We could forget all about it and head back to the city."

"What about our stuff if we walk?"

"We take what we need and get the rest in the morning."

"I'm not leaving my guitar!"

"I'm not the one who needs tuition."

Adam pursed his lips into a soundless whistle, a habit he knew infuriated me. He sucked on breath instead of blowing it out, defiantly not communicating. He looked just like Mimi when he did it, her mouth pulled tight like a draw string purse.

"I never said a word about tuition."

"Your mother calls me every night, insisting I dig up private school tuition."

"I never said a word about private school. Don't lay that trip on me."

"Her gums have started bleeding again, and she has to go back to the periodontist. That will cost me another fortune."

"If she gave up smoking, her gums wouldn't bleed."

"If you're so smart, why can't you pass French?"

"If Mademoiselle Marlowe fails me in French, I am dropping out of school altogether."

"THAT'S ENOUGH WITH THE IFS!" I lost control, but he had made me do it, and smirking, he let me know he knew it.

"If that's cool with you, we can head back to the city."

I breathed deeply to regain my composure. Adam refused to say a word.

"How are we going to get up this hill? That is the trip before us."

"If you go on my trips, I'll go on yours."

"My trip was first!"

I was shouting again, but he had forced me into it. Threatening to drop out was an act of war. He pushed his pelvis forward like some street hood and perched against the fender, supporting his legs on the balls of his feet so an electric tension curled up his calves. It was clear he could pose like that for hours. His body was young and absorbed discomfort with ease. Mine ached from standing in line at the market.

So we compromised; leaving the car at the base of the hill and walking up—hauling Adam's precious possessions. I, at least, could grab for a tree when I felt my feet spinning beneath me, but Adam protected his guitar with both hands.

"What do you mean, dropping out altogether? What the hell are you talking about?"

There were these enormous pauses between questions and answers and counter-replies. Sound had a hard time registering on our numbed brains, and sometimes I had to wait until he was on firmer footing or he had to wait for me to catch my breath.

"You dropped out, didn't you?"

The air was so weightless, talking made me dizzy, but staying silent was worse. If I allowed one single wisecrack to pass, he snarled and issued another.

"And so did Miss Bleeding Gums!"

"We dropped out of college," I answered. "You're dropping out of Junior High."

"This is the age of Instant Gratification. I can't wait as long as you did."

Mimi said my hostile humor brings it out in Adam. I thought the reverse was true. Whoever was at fault, everything grew worse when we had to imagine each other's responses before we actually heard them. It seemed to take forever for sound to leave frozen lips, to float through frozen air, to land on frozen ears.

"What do you know about Instant Gratification? I want you to stop reading New York Magazine while you are waiting to get your braces tightened."

"I know that true creative artists haven't needed school since the beginning of time."

"And who is the true creative artist in this instance?"

"I am. You were. So don't blame me for being a chip off the old blockhead."

"Well, here's news for you, Chip. True creative artists have to pay the rent and the gas and your mother's miserable dental bills."

"Screw my mother!"

I could have wise-cracked that I obviously had and that was the reason we had dropped out of school, but he took his eyes off the road and was unprepared for a frozen branch that whipped in the wind and scraped across his tender cheek.

"And screw you, too!"

I winced and offered support, but his body recoiled from my touch even as snow turned to ice and pain brought tears to his eyes.

"We're never going to get up this hill!" he whined. "One wrong step, and we'll slide to the bottom!"

"Why don't you stop worrying and let me take care of you!"

"When was the last time you took care of anything?"

I gasped that the house was around the next bend, but I turned out wrong and grew secretly convinced we would get lost in the dark or freeze to death before we ever reached the top.

"You sure you've got the right place?"

"Sure, I'm sure."

"When was the last time you were here?"

"Your Mom and I spent our honeymoon here. We didn't have enough money to go anyplace else."

"If it was so long ago and the marriage was such a bust, why shouldn't I worry?"

"Trust me for once. I remember."

How could I ever forget? The minute I started climbing, I remembered Mimi, as exquisite as she had been then. But Adam would never believe she had been, never believe I had thought so, never believe I still remembered.

Breathless beside him was a wily con man: always putting his mother down, always slipping out of demands, always failing her and him, always blaming somebody else. How could he believe I had really loved her and she had loved me and we both had loved him, even before he was born? I would not have believed it myself, except that the memory had been locked in these rocks, and kicking them out of the way, I remembered.

"Because in the 30 years my father has owned the place, he has refused to have this hill paved. My parents argued about it constantly, and I can still hear their fights in my inner ear. That's how, smart-ass!"

My words exploded in puffs of air, but not my memories of Mimi: her tissue paper eyelids so translucent you could see the blue of the veins beneath; her hair, the color of straw, tumbling into twists and curls just like the path before us.

"The house was built by some advertising big shot who had been dumped by his wife. So, he gave up his job and patched together this lonely retreat to devote himself to his painting." Adam had to lean closer to hear, so I was able to steer him along, remembering more with every turn. Me, hanging onto branches, Adam, hanging onto me, three steps forward- two steps back.

"In the end, he went crazy, and his wife took him back, and he owed my father legal fees for the divorce, so the old man picked up the pieces for a song."

That was the way Pop had shouted the story to me that first summer he owned the place. He was fixing the roof at the time, and I was holding the ladder.

"The crazy artist wanted isolation, Jeffey. Don't you see? That's why he picked this spot, way on top of a huge hill, hammering every nail himself, depending on no one, painting daily."

"I want to be an artist," I had said. "A writer is an artist, too."

"And he purposely left the road so bad to give his wife trouble if she came crawling back!"

"I'll move here when I grow up and write my first novel here. I'll make the place famous, Pop."

"Don't do me any favors. Your mother only wants her friends to visit. I like it the way it is."

When my father was in his 30s, he was heavier than I am now, but he carried it awfully well. His arms were stronger than mine, his shoulders broader, his back wider. Yet, repairing the roof in the sun, he moved with a startling grace.

"And what did he give a damn?" I shouted to Adam, sounding just like my father. "Crazy artist used to ski down for supplies in a snowstorm!"

Adam giggled at last, relishing every detail, so that by the time the top came into view, we were hugging and howling, a rare pleasure to share with my son.

I was surprised the trip was over so quickly, but we had maneuvered the terrain with ease once memories had led the way. I had even glanced over the edge from time to time and seen that the worse that could have happened if you drove off a cliff is you would plop into a neighboring cornfield. A lifetime of nightmares over nothing. Still, the final curve took us beneath a frightening arch of posters, nailed to trees and hung from branches.

"No Trespassing!" "No Hunting!" "No Loitering!" "Violators Prosecuted! THIS MEANS YOU." "Post No Bills!" "Dead End, No U Turns!" "This Land Is Posted. Hikers Keep Out. Proprietor, Emanuel Dash, Attorney-At-Law."

One scrawled message had been placed in the middle of the roadway, on a rock which would have torn the guts out of your car if you had failed to stop and read it: "BEWARE OF DOG!"

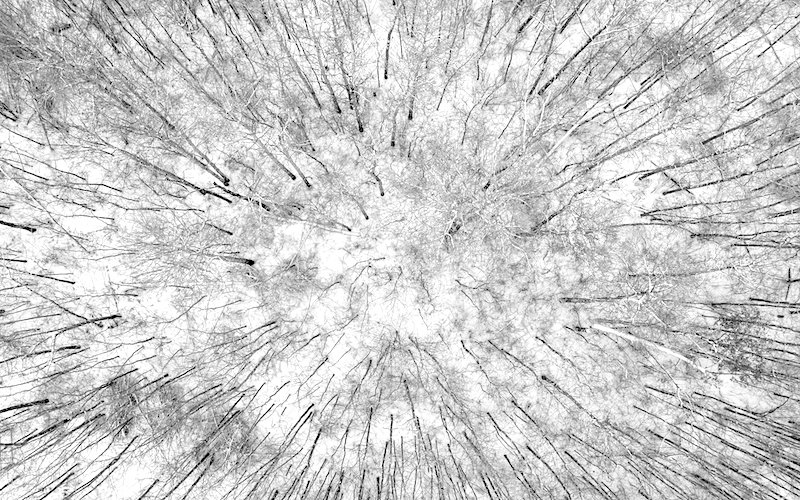

Though not as high as I had recalled it, the top of the hill was breathtaking still. The sky stretched out overhead, taut and transparent like cellophane. The stillness, the silence, was eerie after the chaos of the climb.

It was like landing on the moon, indeed.

Only, straight-ahead, my father guarded the way in my mother's fur coat, earmuffs under an army helmet, ragged shorts belted by rope. His naked legs were shivering in the cold, and on his feet he wore galoshes. I would have laughed except that in his mittened hands he held my old BB gun, which, he had told me a hundred times, could take an eye out if you weren't careful.

"Who is it? What the fuck do you want?" His voice was firm. His eyes were fierce. The gun was aimed directly at us. "What's the matter?" he barked. "Cat got your tongue?"

I clasped a hand on Adam's shoulder and felt him trembling also.

"It's me, Pop."

"You were making plenty of noise coming up the hill! Laughing to beat the band. Having a ball, right? Thought the place was deserted. Right? Thought you could break right in, sleep in my bed, piss in my toilet, drink my booze, waste my water, just like you owned the world!"

"It's me, Jeffrey..."

"This is private property, God damn it!"

"Put the gun down, Pop. You can take an eye out if you aren't careful."

"Private property up to and including that hill you just trespassed on! Didn't you see the signs? Don't you speak English?"

"Your son, Jeffrey. Pop..."

"Lousy sons of bitches, who do you think you are? Nelson Rockefeller? Franklin Delano Roosevelt? Richard Fucking Nixon?"

"Put the gun down. Please."

"Listen to him, Grandpa."

Our words were tumbling on top of one another, so my father did not understand. Worse, everything I said seemed to escalate his madness. I remembered him like this with my mother. Usually, it ended with him storming out of the house and her weeping by the window, worrying until he returned. Once, he threw a vase, and it splintered up and down her arm.

"This property is posted. I don't allow no hunting here!"

"Your son, Jeffrey, and your grandson, Adam..."

I figured the only way to get through was to continue to repeat our names calmly. The worst I could do was to scream in return or, God forbid, weep as my mother used to, rubbing her arm where he had hurt her. Then, he would surely shoot.

"Last time I went to Albany, you vandals used the place and don't think I couldn't tell."

"Jeffrey, Pop... Jeff... Jeffey..."

"Get your ass down the hill, or I'm calling the sheriff!"

"Pop, you don't have a phone."

"That doesn't do any good, saying he doesn't have a phone." Adam tugged to get away from me.

"Don't go near him!"

"Maybe he can't see."

"Can't you see he's crazy? He'll shoot in a minute if you move!"

Adam and I were wrestling as I tried to hold him back and he insisted on approaching my father. Out of the corner of an eye, I could see the old man was growing more and more bewildered. And then, maybe I saw it, maybe I didn't, but it seemed to me he took aim and I in my terror pushed Adam so hard, I sent him sprawling into the snow.

Except for the awful echo of his fall, there was silence.

"Pop, it's me... Jeffey."

"Who?"

"Your son."

As always, he seemed disappointed. But he lowered the gun and I looked at Adam, who fought tears with his mouth clenched shut.

"Jeffey..?

"Didn't you get my letter, Pop?"

"I've got no time for your letters." He turned toward the house as I leaned to help Adam. I wanted to apologize, but he hopped up too quickly, brushing snow from his clothes as we followed my father inside.

My father and Adam trudged down the hill to get our stuff from the car. I was too exhausted to move. I said we would all pitch in tomorrow and shovel the hill so we could get the car off the road and into the garage, and then I would unpack. After all, we had only brought along old clothes, so who cared if we got robbed? But my father told a fairy tale about hunters plundering the neighborhood, and the kid believed every word. The old man said the hunters would break the windshield to get our bags so it would cost in the end and why didn't I think of that?

Adam explained the car was not even mine any more and I never paid the bills I had agreed to in the divorce, which, said my father, made my stupidity even worse.

"In my day and age, couples stayed married, no matter how lousy, so bills for one was bills for both, and don't think your grandma didn't suffer when he busted his marriage, no matter how lousy. I think that's the reason she had a heart attack."

Adam could not resist adding how I had wanted him to leave his guitar, which would have been another tragic loss since he planned to be a musician when he grew up.

"A musician is an artist, too, Grandpa. My dad thinks only writers are true creative artists and performers are second class citizens in the hierarchy of art because they just interpret instead of creating. That's why he doesn't give a damn if anybody steals my guitar!"

My father said Adam was right, even though I inserted that all he ever did was strum on the thing. I never heard him play a single song all the way through. He skipped from vamp to vamp until he drove me crazy.

Adam's eyes filled with hatred, and my father rippled his hair. He found him dry clothing and new boots, and the kid was delighted about accompanying my father up and down the same hill he complained about with me.

So, I ended up alone, faced with the silence, wishing I were back in the city, waking to the sound of garbage trucks and furious drivers honking their horns because they have been locked in by double parked cars.

HAARNK-HAARNK-HAARNK.

A howl of rage. A wail. A wild animal, caged. Imagine, just starting out, first thing in the morning, finding yourself imprisoned. Imagine your fury, haarnking your heart out, still ignored. It shattered my eardrums as I rolled out of bed, brushed my teeth, made coffee. It always took me a while to figure out what was going on, and when I did, I'd smile.

All day long. I'd have the radio going and the telephone ringing with Mimi complaining or an editor screeching over a deadline. For years, I had been talking my way out of trouble or into it, hanging on by a flapping tongue so when, for an awful moment, I was too tired to work and no one was calling, I'd go to the market and fight with the girl at the check-out counter.

It may have sounded crazy, but it was saner than living up here like my father, fearful of phantom hunters. The silence had pushed him over the brink.

"I'd be fine if it wasn't for these fucking hunters. Think the place is Central Park even though it's posted. Next time I see one, he gets it smack in the eyeball!"

So said my father when I asked how he liked living here alone. He has always answered my questions with threats, terrifying me as a child.

"A BB gun may be a toy, but you can still take an eye out."

"I know, Pop. You've told me a hundred times."

"Well, maybe if I had done it, you'd have finally paid attention."

Adam had been laughing since we'd arrived, and once again, his howls slashed the air. He doubled over in his chair, clutching his stomach, drawing his knees to his chin, clapping his sneakered feet.

"Lucky your Daddy said his name nice and clear, or he'd be blind in one eye by now! Pow!" The old man pantomimed a rifle and took another belt of Scotch. "I thought he was one of those hunters and you were also, only a midget, when a little bird whispers into my ear, 'Hey! That's no hunter! That's what's-his-name! Your son! The Writer Who Never Earned A Dime.'"

Adam's laugh flew to falsetto. "Grandpa! Grandpa! You'll make me pee in my pants!"

"Pee outside," my father commanded. "This is not the city where you can flush a hundred times a day. In nature, you have to learn to conserve."

Adam obeyed, and my father was lulled by the hissing sound. When Adam returned, the old man had fallen asleep, lips puckered around another "Pow!" and the kid giggled and whispered, "The Writer Who Never Earned A Dime," but I refused to defend myself.

Instead, I scribbled notes on the perpetual pad in my lap. It was such an old habit, Adam paid no notice. Years ago, he had asked what I was writing. "A novel," I lied, and he still believed me.

He plucked at his guitar. I plucked at my pages. We have survived many awful hours this way. Only, the silence woke my father.

"I've got deer!" he roared as if he had never slept. "Plenty of deer. But it was nothing for nothing when I grew up in back of a candy store. The big spenders want deer, wait until I put a ski lift in. A hundred bucks a night, they'll stand in line to get a place! What do you think, I'm a dummy?"

He fell back asleep, snoring contentedly, and Adam strummed his guitar once more. What he did was doodle and pluck and fool around until his fingers fell into a melody, and that was when my ears perked up. As soon as I felt a glimmer of fatherly pride, he stopped the tune to doodle again. And the sound was such an echo of what I did on these pages that I could not stand to listen.

"Hey, Adam," I whispered, hoping the old man would stay asleep.

"What?"

"I'm sorry."

"Sorry for what?"

"For pushing you."

"When?"

"When we first got here."

"Oh."

"He was in such a crazy state."

"That's cool."

"I didn't want everyone talking at once."

"I don't know why you're so scared of him."

"Scared of him? He was holding a gun!"

"A BB gun."

"You can still take an eye out."

"You really believe he would do that?"

"I'm trying to apologize."

"I said it was cool. Didn't I?"

Abruptly, my father woke. None of my plans worked out around here.

"I don't give a damn if the fucking world blows itself sky high. This is my fucking world, and I'm king here, and anybody wants to argue gets his ass blown off!"

His beard and chest hair was snowy white, but there was nothing frail about his arms or his shoulders. His skin was leathery and still tanned, and his belly overhung his belt with majestic ease. His sawed-off shorts must have been 30 years old, and his legs seemed frail, almost too spindly to support the bulk of his torso. He jiggled his false teeth on and off his gums, and when his cheeks collapsed into his mouth, his face was very old.

Mimi and I met at an audition for a student production of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? She read for the shrewish wife and I for the young stud, but neither got the part, and she claimed it did not matter because she wanted to be a painter, not an actress, since her analyst had said only those who originate the work were true creative artists. A performer's function was merely interpretive, so they were second class citizens in the hierarchy of art, and I answered that, if she gave me her number, maybe we could go to the Museum of Modern Art together.

I watched as she doodled her name, "miriam wolfson," all small letters, leaning over to inquire if capitals were second class citizens also, and her lips puckered in disdain.

"Capitalization of your name is a distortion of reality because you are not the center of the universe. Art is the center of the universe, and everything else is a second class citizen. Matter of fact, performers are third class citizens in that hierarchy. Art first. Painters second. Performers third."

"What class citizens are analysts?"

"You hide behind hostile humor because of your insecurities. It is a sign of narcissism that you feel your name is more important than any other word."

She did not speak, she lectured, giving the impression she and her analyst had discussed every philosophical question of the ages and had found the right answer to each, and I was so confused at the time, I needed to believe somebody had the answers to something.

"Capitalizing your name is just a custom," I gulped. "Like capitalizing God."

"I don't do that. I'm an atheist. All true creative artists are atheists." Even then, her lips were curled around a cigarette, and she dripped ashes onto the floor with such defiance, I proclaimed I wanted to be a writer, not an actor, so it did not matter that I had not been cast, either.

I loved the way she waved her cigarette in yellow fingers, creating perpetual fog, inhaling noisily, exhaling through her nose, sucking the smoke back in with relish. She lit one cigarette from the butt of another and dragged on the new while she stubbed out the old into her cold coffee cup.

She had been a slob even then, but her eyelids were like butterfly wings, and every time she blinked, my heart fluttered.

"Writers are true creative artists like painters, not merely interpretive second class citizens, aren't they, Miriam?"

Or third class citizens. Whichever the hell it was.

"You can call me Mimi," she replied, blushing as if she had asked me to touch her secret, softest part.

TWO

It was morning. The fire crackled in the living room. The oven warmed the kitchen. Still, we dressed in sweaters and coats and earmuffs and mittens and long johns because my father kept the thermostat low, cursing the oilman who demanded an extra fee to drive his truck up the hill.

He told Adam about living in the back of the candy store with his mother and sister after his father died. Still, he survived.

"Survival of the fittest, Adam. That's your Grandpa's philosophy."

"Grandpa, that's Darwin."

"Did he drive a cab all day, cover the soda counter on weekends, graduate law school at night? My family sat on seltzer crates to eat. I won't stop complaining until the bastard is fired."

"Who, Grandpa?"

"The oilman."

"I thought you meant Darwin."

"I have a stack of letters this thick," said my father.

The refrigerator was bare, but the shelves were stocked. No eggs. No milk. No bread. He apparently survived on canned chili. I made tomato soup and sardines for breakfast, and even Adam ate with gusto.

We had all awakened early. The cold made us hungry, and the sun on the windows cracked our eyes wide. I remembered summer streams and chirping birds and rustling leaves, but in the winter nothing moved.

Everything was new to Adam, so he hopped out of bed, eager to embrace the cold, and my father showed him how to dress without exposing skin to the elements, how to flush without wasting water, how to build a fire to last all day.

They trotted around like a pair of clowns, sweeping ashes and gathering kindling while I prepared our exotic breakfast, and afterward my father marched us about, seeking out leaks and collapsing beams, pouncing on spots requiring immediate attention. From the look of things, he never did more than march and seek.

Then they started shoveling the hill since he claimed the neighboring farmers would steal the tires off the car and he was amazed at my lack of survival instincts. He told Adam what a lousy driving student I was, how I nearly barreled into a tree because I had tried to turn left when he had said to turn right, and the kid's laughter punctuated the story like static.

"I knew the little bastard couldn't tell left from right, so I made him wear rubber bands on one wrist. Do you think that helped any? Not on your life. Up here, on a mountain top, the jackass wouldn't survive a day."

The old guy never missed a punch line. The kid was the perpetual straight man, and I was the butt of every gag. A new Three Stooges.

My father unearthed the typewriter I used in high school for me to work on, the one I was going to write my novel on. He was wrong when he called me "The Writer Who Never Earned A Dime." All these years, I have supported Mimi and Adam in middle class splendor in Rego Park and my own humble lifestyle on the upper west side of Manhattan. Mimi worked, but I paid for her massive periodontal bills and the kid's braces and "medical extras" like vitamin pills and summer cabanas and cable TV and magazine subscriptions Mimi claimed were "educational." And don't forget upkeep on that dismal car. Trouble is my father did not know how I earn a living. Neither did my son. The taboo started to protect Adam, and according to Mimi's analyst, his ego was still too fragile to bear the burden.

What I did was write sex stories for male magazines. Not Esquire or Playboy or other chic slicks. Grimy rags for flakes and quickie novels for "underground" publishers. I had several pen names, so nobody knew. I was in solid with a couple of editors. It was a formula business, and I was an old pro. First, I turned out ten times more outlines than sales needed for survival. Then I hovered over the mailbox, waiting for the bounces. There was some predicting what would sell and what wouldn't, but one house would love what another would hate. Only the rates were low, so I had to know quickly to keep the mail moving and meet my quota to pay the bills.

Sex on wheels always sold. Cycle stories. Airplanes. Drag races. I'd do an outline with a stationary couple and get a bounce. I'd put them on wheels and resubmit. Bingo! I've got a winner. A good title helped, and it was an asset if the villains were upper-class. I once did a piece on how big-shots screw stewardesses in those tiny airplane johns. My editor was ecstatic.

Anything tied to the news was good. I read all the papers for inspiration. Youth stories were always fashionable. How your kids were getting more than you were and in what perverted ways. There was constant interest in the super-natural. Getting blown in the dark by a Martian. Spy stories were always successful. How the bitch tried every trick to get the plans but at the last minute our hero sensed danger and held back.

It was a tough racket. There were amateurs galore. The editor turn-over was high. The anxiety level was worse. I deserved credit for sheer survival, but Mimi sneered at every sale. She said my humor was hostile to women and I could not even explain to my son that I get paid by the word, every one chock full of juice, so I had to sell twelve stories and two books a month just to stay afloat.

Still, no matter how drained, I planted myself at the keyboard to produce another plum, and now it appeared, instead of relief, I had to up my output to pay for private school.

And that was the reason I was too busy to shovel: banging out hostile humor on a remnant of my youth.

The house had sunk into the ground, or at least half of it had, so it seemed cockeyed and crippled, and you could not imagine it ever having been new and loved. But beneath the peeling paint, you saw once it was. A huge window in the living room took advantage of the view. A sweet archway had been carved above the door. A hand-made weathervane sat on the chimney.

My father had added a porch to the kitchen, piecing it together with mismatched lumber, out of proportion to the rest of the structure. He had unearthed a supply of paneling remnants and used them to create a ceiling. He had made repairs sloppily, patches on patches, regardless of shape or color.

Every room was lined with pails to catch the rain, but he had a new project in mind. He planned to create a leak-proof roof by nailing tin traffic signs over the weak shingles. "No Parking." "One Way." "Speed Zone Ahead." He had already started to steal signs from the highway, and Adam offered to help.

The house leaned like a crumbling wedding cake, weighted by sagging drainpipes and screen doors hanging askew. Whatever was shiny had rusted. Whatever was solid had cracked. When my father bought this house, he was only slightly older than I am, and I was only slightly older than Adam, who slept now in my bed, in my room, beneath photos of Norman Mailer I had pasted on the wall. My father slept in the bed he shared with my mother. I had the sofa in the living room, but the pillows were hard with memories.

He bought the house without consulting her, partly as a cockeyed trade with the crazy artist. My father said we would use it for summers and then they would move here when he retired so he could hammer to the skies and no one would stop him.

She said over her dead body—which was exactly how it happened.

"He doesn't give a damn," my mother used to weep. "Not about you. Not about me. What does he care it's a hundred miles from nowhere, up a hill so steep you can't get the mail, not a neighbor in sight, so quiet the crickets will drive us all crazy, so dark we'll be murdered in our beds?"

She had been a tiny woman. He had been, and was, a massive man. But her weeping overwhelmed his hammering, and still it haunted the room.

The old man never asked why we had come to visit because he sensed it would cost him, and my tongue was so thick with memories, I could not get the words out.

"I have to wait for the right moment, or else he'll turn us down for sure," I explained as Adam walked beside me in the sulky position I hated. He plunged his clenched fists into the pockets of his coat and drew them together so they met in front of his crotch. He could pace like that for hours, refusing to release his hands except to fiddle on the guitar.

"There's really no hurry," I simpered. "The new term doesn't start until after new Year's."

His body became a coil of tension. His back was hunched, his arms rigid, his walk careful and prissy. It was a statement of total withdrawal, and it made me want to scream that he should cut the crap and take his hands out of his pockets, but he would only stare back and shrug that I was the madman, not he.

"And you're having a good time. Aren't you?"

Mimi claimed he was getting more and more withdrawn, and Mademoiselle Marlowe said there were signs he was turning schizophrenic.

"Say something, for crying out loud!"

"He's such a sweetheart. Why are you so scared of him?"

"Who the hell says I'm scared of him?"

"What do you think, I'm a dummy?"

"No. I think you're a smart-ass kid who doesn't know when to keep his mouth shut. And, maybe if you did, you wouldn't have failed French and we wouldn't be here in the first place."

"You'd better chill out. You're saying things you are going to regret."

"And he's not such a sweetheart, for your information. He never gave me anything, and if he turns me down now, I'll kill him. I'd rather see him dead and buried than give him the satisfaction of groveling."

"You're heading for another psychotic episode," Adam said. "Just like you had with Mademoiselle Marlowe."

"Don't psychoanalyze me. You sound just like your mother."

"Who the hell else should I sound like, shmuck?"

Adam cocked his head and glued his glance to the skies, absorbed in his own tuneless whistle, looking, for all the world, like a schizo. This is the age when it happened, Mimi said. They overdose on drugs and develop the screaming meemies, anytime, day or night. They lock themselves in their rooms and starve until bones show through their skin.

"He made my mother miserable with this crazy house, but he wouldn't spend a dime to fix it up, and now he's afraid because I'm the one who knows it."

They take fistfuls of pills and go up on the roof and try to fly.

"You got all wound up with Mademoiselle, too, and that's why you cracked up like you did."

"So he's just dying to prove he's the sane one and I'm the loony."

"He probably can hear every word. Sound travels like crazy up here."

"If there is any reason you have to rush back, just say the word, and I will ask him today. That's how scared I am of him!"

"You don't have to ask for anything on my account."

"Don't be an idiot. What will you do if I don't?"

"Pick up my guitar. Travel around the country."

"You've got time to start a career."

"Things have changed since your day, Dad. If you don't make it young, you don't make it."

"Adam, you're only thirteen."

"One flick of the wrist, and I've got busloads of 12-year-olds hot for my bod."

I turned to him in amazement. The giggling boy had only been trying to tease me out of my fury, but I grew suddenly scared that I would screw up with him—the way I have with everyone else—and could not giggle in return.

One reason my father loved the house was that it gave him so much storage space. Every time my mother refurnished, he dragged the old junk here. And neighbor's old junk. And junk he picked off the streets. I was seated at a table covered with mismatched oilcloth, one broken radio on top of another, surrounded by chairs, splintered and taped. The kitchen shelves sagged with unnecessary dishware, supermarket give-aways, grimy canisters, plastic flowers coated with mold.

The other two were whittling walking sticks with such concentration, I dared not say a word, but the silence allowed buried images to rush my brain. I recalled one afternoon on the very couch Adam was seated upon. Mimi and I had made love right there, out of control and unafraid.

I remembered that afternoon. The hours have been hoarded here. I could still smell her body in the cushions. I could not recall what had happened before or after, and there have been so many bodies since, but I saw her beneath me as easily as I saw, out on the lawn, under the snow, a pile of rusted auto parts, broken bikes, empty crates.

My loony father throws nothing away.

Right from the start of the fall semester, Mimi had been getting notes from Mademoiselle Marlowe that Adam had been causing fights and talking back and cutting classes and cheating on tests and worse. I hadn't sold a thing in weeks when Mimi called to say that Adam had hidden in the coat closet and refused to come out. He had torn up his homework rather than have it corrected. He had passed dirty notes around the classroom and drawn obscenities on the blackboard. Mimi said it was all my fault. I was an irresponsible, woman-hating neurotic, and Adam had picked up my sexism and was taking it out on Mademoiselle Marlowe.

I had not been out to visit in months. Mimi claimed the least I could do was send the money I owed, but if I had any feeling left in my selfish body, I'd take him to school and talk to Mademoiselle Marlowe. Then she started to cry, which has always pushed me into heroics, so I agreed to go.

The snow fell so regularly, almost without movement, like a polka dot curtain in the window. Still, my father and Adam tackled the hill each morning to get the car up. He insisted they could shovel snow faster than God could replace it. I prepared a hot meal for their return and then listened in silence as Pop crooned how his client, the crazy artist, sold for a song when his wife took him back because he owed so much money for the divorce.

"And this guy was no dummy. He had talent up the kazoo, you hear? Built this house from scratch, hammering every nail, depending on no one. Crazy artist used to ski down for supplies in a snowstorm. Did I ever tell you that, Adam? What did he give a damn?"

"So what happened, Grandpa?"

"Because he was in love, and when she snapped her fingers to come back, the shmuck would have turned the place over for a bus ticket if I hadn't taken pity on him. Seventeen thousand for a house and five acres, two and a half hours from Manhattan, and he left all his paintings for me!"

He laughed,and we joined him, all of us pretending to enjoy the gag. But he was drunk and Adam was confused, and my mind was beginning to cloud.

"A winner grabs the world by the tits and never takes his eye off the ball. That's what your father didn't learn when he was as old as you are."

I had spent hours staring into those abandoned nudes of the crazy artist's wife. My adolescent eyes had wandered over her voluptuous hips, breasts nippled by inky buds, thighs soft as the velvet lining of a jewel box. My father has used them to replace broken windowpanes, cover cracks in the ceiling. The entire ramshackle house is a tribute to his triumph over the painter's love for his wife.

"I figured, at least, with 17 grand in his pocket, he could build another dollhouse when she kicked him out again."

Dollhouse is right. The rooms were tiny and the ceilings were low. The floors slanted. The doors stuck. Still, Mimi and I discovered that the living room was designed for making love before the fire. When we lay there together, we could see the sky through the window, pinpricks of stars peeking through. It was like sleeping outside on soft leaves, the moon at our heads, the fire at our heels. When we started to move, the floorboards creaked, the windows sighed, the walls breathed with us until the entire room lifted from its moorings, a rocket ship propelled by my pelvis.

"If I was 20 years younger, I'd peddle those paintings myself. Make me another fortune. If he wants them back, he'd have to sue, and I'd win."

When we rested together on our backs, the house resettled into the earth. The roof covered us like a quilt, and our nerve endings crackled along with the logs.

"Thirty years ago, I knew how to be a winner—never take your eye off the ball—and that's when I bought this house. Ask your father if that isn't the truth."

What was true was that he had plenty of money, and he had been right about soaring real estate values. But in matters of love, Pop, we were both losers. The crazy artist, on the other hand, did not build this house to escape his bitch of a wife. He built it to win her back, and it worked.

But me and my father, we have both lost our loves, and there is no way they will ever come back.

They finally finished shoveling, and my father drove the Toyota up, Adam hanging out the window and singing, "Hooray for the red, white and blue!" They slid it into a spot they had cleared in the garage next to my father's Cadillac, as if the big car had given birth to the little, and they danced around it in triumph, making up songs and victory cheers.

I watched from the porch and laughed until tears froze at once on my cheeks as my father dug into a corner for a tambourine for Adam, a toy trumpet for himself, and the dance moved out from the garage, my father leading, my son behind, a Cadillac and a Toyota. They tumbled over each other in the snow and tossed some in the air like confetti and tried to get me to join but I wouldn't.

Only now do I understand why it was important for him to move the car and what the celebration was all about. It was his way of saying that he was glad we had come and he wanted us to stay, and I was suddenly sorry I had not responded by rolling around in the snow, also.

Every day got easier. My father and Adam emptied closets, and the old man loaded the kid with white on white shirts Adam found stylish, a carton of old 78's, a felt fedora Adam wore constantly. Where in this maze were the bankbooks, I wondered.

The two of them could be burning garbage outside, yet Adam's laughter circled the trees and invaded the house like a bird. And not his strained city laugh, either. The sound was reckless and airborne, and the collapse of terrors could be heard in each giggle.

I was getting some work done, and my rattling typewriter comforted the others. At dinner, we managed a conversation, and afterward there were long pauses as we drank before the fire. My pen forever scratched at my pad. Nobody mentioned the problems that brought us and still awaited us nor how we could solve them and when we should leave. Adam tuned his guitar. My father cracked a joke. Adam giggled, but I had missed the punch line because I had been listening to echoes of Mimi: "Mademoiselle Marlowe thinks he needs special attention, so you'd better dig up private school tuition or I'll drag you through the courts to pay. If he ends up schizoid, the guilt will be yours, not mine."

My father, of course, heard nothing of this. Now that we were driving down the hill to shop and I was doing the cooking, he had soda with every meal, fruit after lunch, cake for dessert just like he used to when my mother was alive to complain: "What kind of nut buys a place like this, hoarding jigsaw puzzles with missing pieces? For crying out loud, throw out some crap so a person can breathe around here!"

A chorus of sour women hummed in my head. Sometimes I sounded like them, and often I thought like them: "Listen here, Schizoid! If I put up with my lousy father and still hung onto sanity, you can do it, too! You will not fall apart on me. You will not leave me to pick up the pieces and haunt me with those childish eyes like the crazy artist's wife! If I can walk and talk and pretend to be a man, so the hell can you!"

Sometimes Adam looked at me with such hurt, I thought I must have actually yelled it. But my father had not wakened, so I probably hadn't. Then I wondered if the poor crazy bastard—my son, that is, not my father—I wondered if he was so angry because he could read my mind.

I told my mother that I wanted to live like the crazy artist when I grew up, on top of a hill, and she said my father was the crazy one.

"Don't say he's crazy. He isn't crazy."

"Isn't it crazy to buy a fully furnished home without even asking his wife, and isn't it crazier still to pick up junk off the street so he has broken lamps on every broken table and stolen ashtrays and matchbooks he can't resist even though he doesn't smoke and I don't smoke and God forbid, you don't, either?"

"Of course, I don't."

"So what smokers are coming to visit with that crazy hill the way it is?

"That doesn't make him crazy."

"And don't forget placemats he takes from every luncheonette and enough toothpicks to stuff a horse. If that isn't crazy, what is?"

What had he done to fill her so with rage? They fought the same battles over and over, just like Mimi and me, when things went sour and all we ever argued about was who should take out the garbage. But, in the kitchen, the ancient refrigerator was chugging, and I could hear both women weeping in the noise.

THREE

Somehow, sitting in the living room, staring at my pad, I had let an important moment pass. I could only piece together the conversation after the fact, but I gathered that Adam expressed to my father his concerns about being so short.

The kid was short. Big deal. Was that the cause of his schizophrenia? He could have mentioned it to me.

"I was short for my age," I would have told him. "All my friends were. You'll shoot up. Matter of fact, for one two-week stretch, I was the tallest kid on the block and got picked for all the basketball games."

I entered the conversation as the old man was describing how short my mother was, and he held out his palm as if she could perch right on it.

"That's how tiny your Grandma was, Adam. You take after her."

"Pop, don't be crazy."

"Another county heard from. We thought you were writing your novel."

"He wants to hear that he will shoot up, not that he'll be stunted forever."

"Who said he'd be stunted forever? Did I say that, Adam, or is your daddy making up stories again?"

"You're talking about Mom as if she were some pigmy and telling him he takes after her. How is that supposed to be reassuring?"

"Just keep scribbling, will you?"

He had been drinking since dusk, and I suppose I had had a bit too much, myself. It does not matter. An explosion had been brewing since we arrived.

"I was short for my age, too, Adam. All my friends were..."

"Who's talking about your cockamamie friends? What makes you think you know the answers to everything?"

"Matter of fact, for one two-week stretch..."

"We were talking about your mother, may she rest in peace."

"You were making her sound like a shrimp."

"Don't start defiling the dead around here."

"She was a perfectly normal-sized woman. Maybe five foot two."

"The woman was a bird. Maybe four foot two."

"You're crazy! She always said it, and she was right!"

"She never said such a thing in her life."

"Stealing placemats with every cup of coffee and enough toothpicks to stuff a horse! If that isn't crazy, what is?"

He hauled himself out of the chair, face flushed, wrinkles crackling, weaving on his feet. "The woman is dead, Mr. Writer Who Never Finished College! Does it matter what lies you tell?"

I remembered him like this when I was a boy. I remembered him throwing the vase.

"This is so dumb," Adam moaned. "I don't understand why you are fighting."

"Don't get smart with me, Mister Writer Who Never Earned A Dime. I'll smack your face. You think I'm proud of the mess you've made of your life? A son is supposed to give hope to his father, but you, you're a 100 percent failure in my book!"

His face was so bloated, it looked ready to burst. All the veins in his neck turned purple.

"You'll shoot up, Adam," I mumbled. "All my friends did."

"The woman was a bird! That's why we're fighting! I could lift her in the palm of my hand, and if anybody says no, I'll crack him in two!"

He raised a fist high in the air and posed before me, trembling.

"All right, Pop. All right."

My mouth went dry with terror. Adam looked away. Tears threatened all our eyes. Finally, Pop dropped his arm and stumbled to the kitchen for ice cubes.

"Why can't you keep your big mouth shut?" the kid sneered.

"All right, Adam. All right."

Adding a pat of butter to soft boiled eggs to make them even creamier. We ate pears and bleu cheese and did the crossword puzzle with such communion that we had to make love when we filled the final space. There was a whole world of sensuous delight Mimi and I discovered here. Wine with a picnic lunch in the sun and napping, afterward, entwined in each other's limbs.

FOUR

My father and I did not speak for a whole day after the explosion. Adam shot poisonous glances at us both. Three loony birds on top of a hill, flapping our wings as threats.

The old man, of course, talked endlessly to Adam about how he had met my mother, how much he had loved her, rubbing it in that she was so tiny. I dared not contradict.

"All my life, I was surrounded by ugly women. My mother was a horse. My baby sister looked just like her. Client's wives and bookies' girlfriends and frightened hookers were always calling in the middle of the night for legal advice or I should come bail somebody out of jail.

"But Dot, when I met her, was silent and small, barely four foot two, with tiny hands and dimples in her cheeks. She had special rings to show off her hands and a special smile for the dimples. She wore a different hat to work every day, some with veils, some with flowers. I had never seen a woman like her.

"I was this up and coming lawyer, always laughing and cracking jokes, and she was this shy typist in the secretarial pool, and if you want the truth, Adam, I was crazy about her from the first minute. But she didn't know I was alive. Or so I thought. Every time I passed her desk, cracking a joke that set the other girlies off, she buried her head and typed fast, and how was I supposed to know?

"But I was skinny then, and good looking, too, so all the girls were after me. The same thing will happen to you, Adam. If you have any doubts, I have pictures to prove it: me, skinny, and Dot in a hat."

Mimi had not aged well. She drank too much, blamed it on me. She had stopped painting years before; the brush had dried up in her hands. Before we split, she used to get depressed and eat whole cheesecakes in a single sitting. She was still trying to get the weight off her hips. I remembered when we comforted each other, calmed each other, urged each other on. Now, it seemed, we passed on terrors like relay racers.

"You're smoking," I greeted her the morning I arrived to pick up Adam. "What's wrong?"

She led me into the living room, which as usual, was a mess. Adam's clothing, books, magazines, a pile of gardening tools. Every picture on the wall hung cockeyed. Every ashtray overflowed.

"Mimi, the periodontist told you a million times how smoking aggravates your gums. Last time I was here, you promised to give it up."

"How many years ago was that?"

"Months, not years."

"How many months?"

"Who remembers?"

"Adam remembers."

"Mimi, what's wrong?"

Even her hair was frantic. Her eyes, shining dark marbles when we were younger, had tightened into suspicious slits.

"What could be wrong? My kid is getting thrown out of school. His father, of course, is 40 minutes late. Mademoiselle Marlowe expected you at nine."

"Well, I'm here now, aren't I? And I'm taking the kid to school, aren't I? And I'm getting down on my hands and knees before this almighty Mademoiselle so she doesn't have him suspended. And I'm sure to succeed, aren't I?"

"Hallelujah! Norman Mailer is here! Forty minutes late, of course! But I'm still supposed to be grateful!"

"I know I am always late and I owe you so much money and I didn't turn out to be the great American writer, either."

"Please keep the details of your disgusting career to yourself. Adam can hear every word."

"Some day he is going to learn the truth, Mimi."

"My analyst feels his anti-social behavior is due to the distortions of his role model."

"Does your analyst do oral surgery, also?"

"Adam!" she shouted. "Your father is here!"

He did not appear, and we were left, smirking at one another because we had gotten under each other's skin so quickly.

"And it's none of your business whether I smoke or not."

"I pay the bills."

"Since when?"

Mimi shut her eyes as if she could make me vanish, and Adam, suddenly on the stairway, took up where she had left off.

"Hello, kid. How the hell are you?

"How the hell should I be, Norman?" he sneered.

The three of us went into town. When I was a kid, there was only one grocery and a gas station. Now, there was a mall with a movie theater, even a pizza parlor. My father pointed out each new addition as if he had built it himself.

We had been tiptoeing around one another for days, so the trip was a relief, and I announced that, in all the time we had been there, I had eaten no junk food, three straight meals, lots of fresh air, working and sleeping. So I offered to treat to a pizza, and we ordered a whole pie with pepperoni and three large root beers.

We were like children, cheese dribbling down our chins, cursing so strangers stared, each talking faster and louder than the others. I told them how well I was working, and Adam said my novel would win the Pulitzer Prize. My father said I had better not put his stories into it. He was thinking of writing a book, himself. Our voices and giggles were so alike, I would think it was me, babbling and laughing, but it was one of them.

"Then, one day, out of the blue, I plant myself on top of her desk so she can't pretend to ignore me and type while every other girlie has her ears pinned to listen. I'm in charge of the office Christmas party, I tell her, and if she volunteers to help decorate, I can get her the afternoon off to go shopping for tinsel with me. I had noticed the sense of style in the hats she wore and the rings on her fingers, so I figured she was the girl for the job, and she must have turned a hundred colors, but sure, she says, she'll go. Why wouldn't she, for crying out loud? An afternoon off is an afternoon off, and she figured I was some up and comer to be able to finagle that for her.

"Well, Adam, we never stopped laughing the whole afternoon. I don't even remember why any more. Don't forget, this is 50 years ago, I'm talking. We bought tinsel and crepe paper and grab bag gifts for everyone. That was her idea. I spent money like water. It was all from petty cash, but she was impressed by the way I did it.

"By the time I took her home, I knew two things for certain. Number one: she was laughing so hard, I could do anything I wanted, and number two, I was in love, so I'd better watch my step!"

My father was teaching Adam to drive, and I was nervously alone. Nervous because my father was blind in one eye and had lost his driver's license and I was sure he would crash and kill them both. Nervous because I remembered him barking, "Turn right! Turn right!" when I turned left and nearly barreled into a tree.

Nervous because it was so quiet, I found myself talking aloud like he does, recreating arguments, first taking her side, then his, about how crazy it was to live here and what use was that pile of shoes without tongues? Nervous because I sneaked into his room to look around and one wall was covered with moldy cartons containing his old legal files, but there was a new one filled with his present obsessions. He was still fighting the phone company over the bill that caused them to disconnect. He was threatening to take the revocation of his driver's license to the Supreme Court. He was suing to collect workmen's compensation benefits, claiming my mother died of a work-related injury while employed as his secretary.

She died of a heart attack. She had never worked as his secretary. The case had been turned down twice, and he had to drive, unlicensed, to Albany for another hearing.

The papers were neatly filed, but each letter was crazier than the last: misspelled, incoherent, coffee stained. A complaint to the oil company exploded with rage. A Playboy calendar hung over his bed. Cereal box toys littered the dresser.

"I've got one more funny story to tell. Then I'm going to sleep. This is about the first time I brought your grandma home to meet my family in back of our lousy candy store. They didn't know it was lousy, I suppose. They only knew my pop was dead, so I was the fair-haired son and this strange girl was coming to steal me away. So my mother was tight lipped, and I was worried she would say something mean, on top of worrying how Dot would react when she had to sit on a seltzer crate.

"And I had warned them in advance that she came from the Bronx, where they had real kitchen chairs, and I must have laid it on too thick about her being short and delicate. So in I walk with Dot, and my mother stares, and my baby sister, Celia, finally pipes up to break the ice. 'She ain't so short,' she says."

My father laughed so hard, he choked on his cigar, stomping his foot to stop himself. Trailing smoke, he headed for bed, pausing to pee off the porch, chuckling, "She ain't so short!" over and over. Adam and I were left in our usual discomfort. Only this time, he did not turn to his guitar.

"It's time," he said.

"Time for what?"

"Time to ask for the money." He seemed awfully sure of himself. "What are you so afraid of?"

I was afraid my father would say no and Adam would be crushed. I was afraid my father would say yes and I would look like a fool for being so afraid. Or he might have said yes, and I would sign all the papers, and at the last moment, he would leave me holding the bag.

"I'm not afraid. What makes you say that?"

"Don't you realize the point of that story? About her not being so short? He's apologizing to you for yelling. Remember, that's what the argument was about. It's time to ask and go home."

"Adam, not yet. We've barely been here a week."

"He didn't mean all those things he said. He's only teasing when he calls you names. When your novel is published, he'll be proud."

"Adam, please. He'll only make another scene."

"If you don't ask, I will."

"Adam, please..."

FIVE

I had not expected Mademoiselle Marlowe to be so pretty. Mimi had prepared me for her youth: not more than 23, just out of Barnard and a year at the Sorbonne. Every time she used a French phrase—and her conversation was littered with "Mon cher, Adam," and "comprenez-vous?"—her exquisite mouth sucked on the sound as if it were made of hard candy.

She had fragile skin and soft hair and sky-blue eyes stretched wide. I could picture her bouncing through Paris, writing home breathless praise, just on the brink of a hot affair, carefully eyeing every guy on the street to make sure she picked la crème de la crème!

The classroom walls were covered with Air France posters and ads for French movies and one large montage, cutely lettered, "Mademoiselle De Paris" in a rainbow of magic markers. There were snapshots of Mademoiselle at the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe and flirting with whatever you call a French cop. She caught my glance and explained how Junior High French was more than grammar and vocabulary. She wanted her students to learn about la cinema francais and tout le monde francais.

Adam was standing awkwardly beside me, and I could feel his body trembling through the floor. All the way to school, he had been doing his tough guy number, but in the classroom the transformation was alarming. His body shriveled. His complexion paled. His head fell forward so heavily it looked like it would tumble off his neck. Both shoelaces had come undone, and they dangled from his sneakers as if I had never taught him to tie them.

Mademoiselle signaled with a shrug that this was what he was like all the time: hostile, resistant, tormented, and I said I agreed with her educational philosophy and confessed I had been a lousy French student myself. But, in college, "I fell in love with Proust and studied until I mastered the language."

"You hear, mon cher Adam? Papa is right. It may not make sense now. It may be boring and difficult. But one day, the glories of French will enrich your entire life!"

"It's like learning to play the piano," I added. "You practice those scales, and voila, you're playing Debussy!"

"Well, I play the guitar," Adam hissed through clenched teeth.

"You don't play anything, so far as I know. You doodle. That's not playing. I never heard you play a tune from start to finish."

"That's exactly so far as you know."

"He doesn't apply himself with discipline to anything," I confided to Mademoiselle. "Which is exactly what we are saying. He doesn't study music. He can't read notes. He never practices!"

"How can you say that?" Adam gasped. "I practice all the time! That's what I'm doing when you think I'm doodling."

"I'm a writer, you know, Mademoiselle. And every artist worth his salt knows you haven't crawled until you have mastered Proust."

Adam turned from us and paced the room, scraping his heels against the floor, rcohenng a finger close to the wall so he threatened to ruin Mademoiselle's montage. How could I have explained to someone as innocent and charming as Mademoiselle that I had brought a kid into the world, and joking and flirting and battling to survive, I had done so much damage, he was cracking up?

"I didn't know you were an artist, Monsieur." She tried to help me out. "Why didn't you tell me Papa was an artist, Adam?"

He sprawled into a chair at the other end of the room, his mouth curled in that infuriating whistle. No one could get through to such a kid. No teacher, no parent, no analyst. A blanket of hostility engulfed him.

"Might I have read something of yours, Monsieur?"

"Oh, the publishing scene is so corrupt, I decided years ago not to publish at all. Lots of us, a whole school of writers, are choosing that private path these days."

"How absolutely fascinating."

She was going to flirt through this session, and so, I figured, was I. Let Adam see that his loser of a father, also a failure as a writer and a lover and a son, can turn on the charm when required.

"All my friends feel that way. We support each other in our isolation from the mainstream."

"I'd really like to hear more about that."

"Maybe some night you'll join us. We often bring guests who are sympathetique."

I winked at Adam, but the kid was not impressed.

Adam was getting up early each morning, thinking up projects, obviously getting ready to ask. They fixed the bathroom floorboards, sorting through a pile of half-rotten lumber planks to replace the thoroughly rotten. Afterward, they went for the daily driving lesson. According to my father, the kid had a natural talent. Not like me.

I could never relax behind the wheel. Never learned to bend my elbows, never steered with one hand like Pop did. Still can't turn the ignition key without a sense of helplessness and bubbling rage. Tension in the shoulder blades makes me drive too quickly, with parched lips and heartbeat palpitating in my ears and eyes aching in their sockets.

He invited Adam out to see the full moon on the snow, and I trudged along behind them. The property ended at a cliff from which you could see the surrounding countryside, sheathed in white satin.

"What do I need the Hayden Planetarium, where they charge you a buck and a quarter and you can't even pee in the snow? Right now, I own the world, and that's something you'll never feel in the Hayden Planetarium. I own all those roads and houses and even the stars and the moon and the sky, and nobody can take that away. You'll learn, Adam, as you get older, everything that means anything, life is going to take away. But damn it, this view of the stars, just let them try, and I'll show them who's boss around here."

"Pow! Right in the eyeball. Right, Grandpa?"

He threw an arm around Adam's shoulder to launch into a lecture about the patterns in nature and how one star connects to another, and the poor dope of a city kid oohed and aahed, and his body leaned close to my father's.

It made me jealous, I admit, and when my father turned away to pee, I whispered, "Adam, please don't ask for the money. He'll only kick you in the teeth."

"Why do you say such things about him?"

"He never gave my mother a thing. He's always sneered at me."

"No! He's proud of you. He can't wait to read your novel. He knows you're a true creative artist. In his own way, he loves you." To my amazement, the kid was near tears. He shook his head to push them away.

"Adam, please don't," I mumbled.

I was not working so well after a while, sitting at the table and pretending to write as deadlines flew by. I listened to Adam and my father howling and tried to laugh at their stupid gags, but the sound would not come. I was afraid I would never finish another assignment or crack another joke.

Every now and then, Adam asked how the novel was going. The question always came after a lull in the conversation, and I could see from his blush how much effort it took. My father always perked up when he asked, awed the kid should tread on such sacred turf.

I was usually taken aback, so I said something absurd like, "Oh, you know how it is, Adam. I spend the whole morning changing a few phrases, and then I decide I don't like the changes and change them back again."

Should I have confessed I am like every other factory hand, hauling the stuff onto the conveyor belt or I start to sink? Still when the system breaks down and I get hit with a string of bounces, well, I get through the bad times, too. And I do it all without grandiose claims about being an artist, having all the answers, skiing down for supplies in a snowstorm.

I survive, God damn it, and that's an art, too. But when I listened to my father finagle about connecting stars so my son leaned toward him, I remembered loving Mimi and then losing her and failing everyone and everything, and all of a sudden, Adam is on the brink of tears and I cannot figure out why.

Well, enough is enough. Nobody wins everything. Norman Mailer had his bombs. So I resolved to ask the loony for tuition and take the kid home before the three of us got stuck here forever, hammering together to the skies.

This happened after a visit to my mother when she was recovering from her heart attack. For the first week, she had been in Intensive Care, always sleeping, barely breathing, and my father and I had been allowed in for five minutes each hour to stare at her pale face helplessly.

But time had passed and the worst was over, or so they had informed us. She had been moved to a semi-private and was sitting up and eating by herself and had even started squabbling with my father. She wanted some cosmetics and a book she had been reading and an emery board for her ringed fingers. My father grumbled that he would not know an emery board if he fell on one, so I offered to get it and drove to their apartment with him.

He looked worse outside than he had in the hospital room. I was afraid he would fall asleep at the wheel and offered to drive but, of course, he would not hear of it.

I said she certainly must be getting well if she needed a cockamamie emery board, but he did not laugh at the joke nor at my effort to reassure him it did not make me smarter because I knew what an emery board was and he didn't.

He managed to park once we reached their building but stumbled as he left the car. I dared not try to help him. He would have been so shocked by my touch, he would have swung out against me as at a mugger. I allowed him to totter along, supporting himself on the fenders of cars, dragging his heels, mouth hanging open, and I kept up a line of chatter about they should go to Florida when she was released. Why spend the winters in New York City? Travel around the world. Spend your money, Pop. There's plenty of dough and then some.

In the apartment, he fell onto the bed, fully clothed and shod, and I gathered her things and left him to sleep. I shouted goodbye from the door and said he should take it easy, but when I hit the street, I realized that the one thing I had forgotten, after all that joking, was the emery board. I could have picked one up at a drug store but was sure she had a special kind and he would make a fuss about my not doing anything right.

So I turned back, muttering all the way about this crazy family and their constant demands and how it was not enough I had to fulfill them, but even then, somebody would find something to complain about.

I had a key to the apartment because I was coming and going so often to get her things and stock the shelves and make coffee, and I used it on my return so as not to wake him. I heard the strange noises as soon as I opened the door, like animal whinnies more than anything, accompanied by loud clomps, so at first I supposed a parade of policemen on horseback was passing on the street. But how could the sound travel so clearly, and when was the last time I had seen such a parade? I tiptoed to the bedroom door to see if a window shade was flapping.

He was on his hands and knees on the bed, banging his head against the headboard. He turned to see who had entered the room, and I could not miss the fact that he was crying. I had never seen him cry before. My mother cried over anything, soaking up hanky after hanky, but my father's tears were like globs of oil. Each slowly descended his face, in and out of wrinkles like a creek criss-crossing a mountainside, taking forever to drip from his chin. He must have been weeping from the moment I had left because his shirtfront was soaked through.

And those awful sounds. It seemed like an enormous moan had started in his gut and snowballed into his chest, only to be strangled in his throat, and the horse whinny that emerged was merely the tip of his grief.

I remember the details because I was frozen in the doorway. He did not seem to recognize me, nor did he seem to care. And I, who had been afraid to touch him in the parking lot, certainly dared not approach him then.

"Pa," I muttered, "please. Everything is going to be all right."

"How can you say that?" he gasped. He did not look me in the eye. He did not seem shocked to hear my voice. "Everything won't be all right."

"It will be. It will. All the doctors say so."

"It won't be. It won't. The woman had a heart attack. The woman nearly died on me. How can it ever be all right?"

"People recover. She'll be good as new."

"The woman nearly died. How can you recover from that?"

"You can. You'll see. Everything will be all right."

"It won't be. It won't. Everything won't be all right."

"It will."

I should have touched him. I should have come closer. I should have, at least, moved from the doorway. But the two of us remained in the same positions, me saying she will and him saying she won't until, finally, his knees gave way. His head plopped onto the mattress, and in a second, he was sleeping.

I watched him for a while before leaving with the emery board, and neither of us has mentioned the incident since.

Mademoiselle glanced at her watch. Then she scraped her chair back: an imperious signal the meeting was over.

"But we haven't discussed the suspension," I gasped. "Aren't you going to forgive poor Adam and let him back in class?"

"Time is up, Monsieur."

I had not scored any of the points Mimi had drilled into me about how emotionally scarred the kid would be, how he might drop out of school and develop the screaming meemies if she failed him, how I would visit regularly to tutor him back to mental health if only she gave him another chance.

"Just a few minutes more, Mademoiselle."

"I must prepare for my next class, Monsieur."

"We're discussing life and death issues here!"

"I have a responsibility to my good students, too."

Oh, this Madame Curie was a bitch, to be sure. Just out of Barnard, a year at the Sorbonne, major in French, minor in Castration. I flashed a look to let Adam know, but the poor kid was slumped in his seat like a psycho. I had seen enough nut house movies to know.

He had his arms crossed tightly over his chest so the white coats would not have needed a straitjacket to cart him away. His right hand was resting on his left shoulder and he had twisted his head around so he could nibble on his thumb. His eyes were pressed shut as if he were trying to lock out the image of his failure of a father, and who could blame him?

Instead of coming through for my troubled son, I had tap danced make-out routines that had been frayed before the kid had been born, and Madame de Stael had been laughing up her sleeve all the time. She cocked a brow to signal she had seen the nut house movies, too, and had spotted this pair of suckers at once. Just give the father enough rope, she had figured, and he would hang himself while the loony-tune son checked into never-never land for good.

She had curled me around her pinkie so that, if I tried to explain, my tongue would turn left when it meant to turn right. All the arguments I had prepared got tangled in my brain, and I did not remember what Mimi had said I should say and what I shouldn't.

"Perhaps we could talk after your class, Mademoiselle. I came all the way from Manhattan to see you. Mrs. Dash and I are divorced, you know, so I don't live in Rego Park. Can you imagine an artist living in Bourgeoise Heaven? I'd go bananas in a week. I am so impressed that you can stand it, a bright young woman, just out of Barnard, a year at the Sorbonne."

"There is nothing to talk about. Is there? It is not me who is unhappy with Adam. Mais non. It is Adam who is unhappy with me. Perhaps, with time, you can help Adam define his unhappiness, and then I'd be enchanted to correct my faults and have him return to class."