Summer at sea, a century ago. The crossing was peaceful. The Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, pride of the Hamburg-America Line, plowed east at 17 knots through a week of small waves while Stearns Carver played shuffleboard with the blue-eyed daughter of Mrs. Lord of New York and Newport. He and Prudence Lord also took long strolls along the deck together, bright mornings after breakfast. At the captain's party the band played "Fancy You Fancying Me" and he danced the bunny hug and turkey trot with her, or at least he tried to. Carver was not a very good dancer, but she smiled at him and said, "You know, it's all the rage in Newport." Afterward they stood at the rail under a full moon, and he kissed her.

But that was that. She and her mother were to spend three months in Germany and Italy, and Carver was bound for Russia. She was, besides, a little... artificial, was maybe the word. And the mamma clearly thought that Carver the young diplomat was a rich man, not the country doctor's son from Maine who had worked his way through Bowdoin College.

Two days later they said goodbye on the dock in Hamburg, and Carver caught the 11:00 AM express to Berlin. It was early July, and Germany was green. He sat by the window as they dashed through an uninteresting low landscape of marshes and farms, carefully tended copses, neat brick villages. He thought idly of what the Russian countryside might look like, of what might await him in St. Petersburg. Soon he slept, for an hour or more.

What woke him was two haughty young hussars in blue who entered his compartment at a stop in some small city. Carver nodded to them politely. One of them nodded in return as the two sat down and began talking. Carver's German was far from fluent, but he could halfway understand them. They talked about girls, but soon it was war, glorious war. When the train reached the outskirts of Berlin after another hour, they were arguing whether machine guns could stop a good troop of cavalry. The cavalry would come through, one said, mit Ach und Krach. By the skin of their teeth?

As the express slowed to a stop in the tall train shed, the hussars stood up to leave the compartment. One of the two was a very young man with a light blond mustache that Carver thought looked ridiculous. He turned to Carver and said to him in English, "You must not think we are anti-English. But you must understand, we Germans will not let you put us in a second place!"

Carver stood up, saying, "I'm not English!" But they were gone.

In half an hour he had registered at the Hotel Albrechtshof on the River Spree. He telephoned the embassy. It was almost six, but Ted Roussel was still there, expecting Carver's call. At 8:30 they met for dinner at a nearby restaurant called the Spreewald, just off Unter den Linden. The evening was pleasantly warm. They sat outside under the thick leaves of linden and chestnut trees as the sun lowered slowly and twilight came on.

Carver and Roussel had entered the American diplomatic service together in 1911, two years ago now. During their short orientation course in the State Department, they had become friends although—or perhaps even because—they came from very different backgrounds. Each had lost a grandfather at the battle of Shiloh. Grandfather Carver had been a corporal in a Maine regiment while the elder Roussel was a major in the 18th Louisiana. Stearns Carver had little money; Ted Roussel, a Princeton graduate, clearly had lots. But that didn't matter to Carver, at least not much, he thought. After all they were both Americans. He was sure Ted was as pleased as he was to be serving the nation.

After their month of orientation, Roussel was sent to the Berlin embassy and Carver to the Department's diplomatic bureau. For two years he worked in the great Victorian building just west of the White House, drafting instructions to posts abroad on a range of mainly small matters, for Mr. Adee's signature. Carver revered Alvey Augustus Adee, backbone of the Department, although he was admittedly less than impressive in appearance. He was a small and rather deaf bachelor with a trim beard that had turned almost white, now that he had spent 30 or was it 40 years in his country's service.

One warm afternoon in April, just three months ago, Adee had asked Stearns Carver to come by his office. Carver walked down the corridor thinking how he had grown to love this place with its high ceilings that left it cool even in summer, the walls hung with portraits of old Secretaries, the swinging doors, even the shining brass cuspidors. It was just what a foreign ministry ought to be... the Second Assistant Secretary waved Carver to a chair by a big open window that faced south, toward the Mall. Azaleas, tulips, and magnolias were all in bloom and Carver could smell the spring world.

The immediate, the Departmental world, was now a Democratic one. Woodrow Wilson had entered the White House in March. He had named William Jennings Bryan, a mighty orator but no diplomat, as his Secretary of State, and then wisely asked Adee to stay on as the Second Assistant Secretary.

"I think, Stearns Carver," said Adee, "we will see major developments in the next several years. I am going off to Europe on my usual cycling trip this summer, and my guess is that the papers will report the fact—not because old Adee is going to wheel his usual thousand miles, but because Adee must not think war imminent, else he would not leave the country. Indeed I do not think war is coming this year. But I am making no bets about 1914, even if for now the German chancellor is saying nice things about England.

"Now to the point. I like your work... and I want you to replace Jack McFeatters as second secretary of embassy at St. Petersburg. Will you do it? If so you must leave soon. McFeatters, as perhaps you have heard, is going to Istanbul to replace Donaldson, who has come down with some very vicious sort of fever."

Number-three in the embassy that was one of our half-dozen major posts? Carver quickly agreed.

Carver thought back now to what Mr. Adee had said, as he and Ted Roussel began their Goulaschsuppe. "You know, Ted," he said, "I'm going into the great unknown. Why, I've never even tasted caviar, let alone met a boyar. From what reading I did on Russia the last couple of months, I sense that the country is flying fast into the future, just as that great Russian writer wrote. Turgenev, I think. Or was it Gogol? Anyway, he said Russia was like a carriage flying along behind a three-horse team, and nobody could tell how far it would go. But I expect I'll still see a lot of backwardness, you know, muddy villages and muddy peasants and priests with long beards. And maybe a war, too; people are talking about that. What do you think?"

"I think they're wrong about war. Of course there's been some frights and alarms, and this Kaiser is a proud Prussian. And they say the Prussians are the only people that's always made war pay. But in the end old Wilhelm is just not going to make war on his grandmama's people, which means the English, and... well, I can't imagine war, I mean a major war, at least in this decade. Mind you, there are hotheads all about."

Carver told him about the hussars on the train. The sky was finally darkening above the city. A waiter began lighting candles on the half-dozen tables of people dining under the summer trees.

Roussel was amused to hear about the hussars. "As I said, there's hotheads everywhere. You remember the war fever before we went to war with Spain. But nobody's setting off mines under German cruisers, at least for now. Those hussar boys will calm down after they do a little colonial service in Africa."

Two evenings later Carver's express had traversed 900 miles of northern Germany and the lonely regions of Russia's empire lying south of the Baltic, and steamed into the great stone capital that Peter had built on the marshes of the river Neva at a cost of ten thousand human lives. It was a hot summer evening in St. Petersburg even though the sun was lowering in the west. He was pleased to find that the Hotel de l'Europe on the Nevsky Prospect, where his new embassy had booked a room for him, was an altogether grand and elegant place, finer than any hotel in Washington—and his room had a ceiling fan.

The next morning Carver set out at 8:00 to walk to his new embassy. The embassy was on Furshtatskaya Street, three streets south of the Neva, but he walked from his hotel north to the majestic river and did a mile eastward along the embankment before turning south. The air was full of scents and sounds: salt water and herring, but also manure; hoof-clops and cabbage cooking and the shouts of a drunken droshky driver; the chugging and smells of delivery trucks, taxis, and a few fine touring cars; many bells ringing in church towers; the smells of freshly cut grass and of flowers, as Carver walked by the Tsars' Summer Garden and its big oaks and elms. He felt excited. It was all new and exotic, not much like Maine—or Washington.

The most recent American ambassador had just left for home, and President Wilson had not yet named a replacement. Angus Weed, the first secretary of embassy, was the chargé d'affaires.

Weed greeted Carver warmly, saying, "I've been looking forward keenly to your arrival, Mr. Carver. You come well rcommended. And I need your help."

Weed, Carver thought, looked to be a good sort, probably in his late 40s, well-spoken. He was also, he saw, a man with a tic that could make his head twitch, sometimes once a minute.

"Mr. Weed, I am delighted to be here. I'll do my best, I assure you… but I have to confess I still know very little about this country. At least I have had the advantage of working until now under Mr. Adee, so I feel I understand what the Department needs and expects from us here... I am almost forgetting to tell you, sir, that Mr. Adee sends his regards."

"I am pleased to hear it. Old Adee is the best man in Washington. Now, let us—" and here came a twitch "—let us call one another by our first names, and see if we can keep Washington well informed about this huge and rotten empire. I tell you, Stearns, it is just that, quite full of rot. But there's much more to it than that. This Russian world is changing very fast. Russia's going to clean out its rot. It is going to be a great industrial power within a few years, and not just steppes producing grain and muddy peasants. I tell you, some of their businessmen are quite impressive..."

Within a week Carver had rented a furnished flat with three large rooms on the Neva embankment, just a half-mile from the embassy. The flat was on the second floor, and the sitting-room and dining-room windows overlooked the broad Neva. Carver acquired a mousy blonde cook-maid named Liliya, who admitted to speaking a little English.

Actually she spoke more than a little, and she had no trouble at all understanding either spoken or written English. She began reporting regularly to a major named Ivan Lomov, her handler at the Okhrana, the secret police, on whatever she learned about Carver. This amounted to rather little, mostly copies she made of personal letters he kept in a drawer. The ones from his father were sometimes puzzling. They urged Carver to keep always in mind what President Hyde had so often said about patriotism, to remember President Hyde's urgings about leading a clean life. Lomov could find no record of an American President named Hyde. Perhaps he was president of one of the American states. (William DeWitt Hyde headed Bowdoin.) No matter, Lomov thought; he had better sources than Carver's letters.

Carver always remembered the first morning in his new apartment, when Liliya served breakfast to him at seven. The sun had risen two hours earlier and was shining bright on the stately buildings across the river and on the Peter and Paul Fortress, a half-mile down the river, with its needle-thin, tall golden spire. It's a noble sight, he thought, but he knew many Russians, thousands at a guess, had been locked up there for opposing the rigid regime of the Tsars. One of the books that had most impressed Carver in his reading on Russia was George Kennan's account of the horrid Siberian prisons, whose inmates included so many sons and daughters of prominent Russian families.

Angus Weed was right. This was a rotten place, even if the economy was growing. Kennan's book was three decades old, but everyone knew there were still many political prisoners and exiles in Siberia. Everyone knew, though the press was forbidden to mention it, that Nicholas II had fallen under the influence of a drunken monk called Rasputin, who was getting the Tsar to name total incompetents as ministers. And everyone knew the number of strikes was steadily growing. But what was really going on among the workers? I really have no idea, thought Carver, and neither does Weed, but I am hearing a little from Ivanich.

Ivan Ivanovich Kozlov, whom the embassy Americans called simply "Ivanich," which Carver suspected was a little demeaning, was the embassy's longtime usher. He was a grizzled fellow although probably not yet 50, he spoke fair English, and Carver found him helpful. One day Carver asked him about himself.

"Well, Vashe Blagorodiye, I mean Your Honor, nobody ever ask me that. I was born in village six, seven hundred versts north from here, muddy place called Konevo. Horse place, it means. Pretty church but poor houses. We was a couple hundred souls. Men beat their wives and drank too much and fought. We farmed like we done back in Tatar time, and we was poor. One year I went barefoot, no shoes, until snow came. But I had a cousin worked here in Piter, and he helped me get job in factory. Men laughed at me in poor clothes, but I didn't drink, saved my money and bought city suit, even went to evening school and learned to read. And write. After ten years I got job here at embassy; been here 18 years, and happy, Your Honor."

"What about the men and women who still work in the factories here? I sense they're not so happy. You had a revolution back in 1905, and the Tsar agreed to a parliament, a Duma, but then he took the power away from it. What next, do you think?"

"Well, I don't know, Your Honor. Of course we loves our Tsar—" did Carver see the man wink? "—but he don't know how bad things are. Too many priests, too many dvoryanye, I mean nobility, they all tell him lies. And German spies, friends of Tsaritsa. I don't know what next."

One day at noon, after Carver had been in St. Petersburg for two weeks, he walked out of the embassy for a stroll after eating a sandwich at his desk. In several blocks he turned a corner and came on a crowd of several hundred people marching toward him. Some were carrying red banners. They must be workers from some factory. They were marching toward Nevsky Prospect, singing, filling the street. He moved off the sidewalk into a doorway.

A platoon of mounted Cossacks galloped in suddenly from a side street, men in gray uniforms on big horses. The Cossacks rode at the workers, who stopped and started turning back, started crowding against the building walls. The horsemen were flailing at the workers with sabers. Many of the people were women. Now they were all rbridgesng down the street to get away from the Cossacks. People screamed and shouted. One woman had a small daughter by the hand but the child tripped and fell. Carver stood horrified as a horse's hoof crushed her skull. The Cossack horses pushed the mother and the other strikers on. An old woman ran to the child, but it was too late. The noise died, and the street was empty except for Carver and the crone and a small body on the cobblestones. He retched and vomited in the gutter. Major Lomov of the Okhrana, standing on the sidewalk 50 yards away, smiled, spat, and followed Carver at a distance as he walked back to the embassy.

Carver looked through the papers the next morning to see how the press treated the incident. There was no mention. Instead the press was focusing on Mendel Beilis, a Jewish factory superintendent in Kiev whom the government was trying on a charge of ritual murder of a Christian child. The Orthodox Metropolitan of Kiev had just sent a telegram to the witnesses for the prosecution, saying they were doing their Christian duty.

Carver went to Angus Weed in a fury. This was an altogether terrible place. Weed looked at him, twitched a bit, and said "I don't disagree, Stearns. But you must keep in mind, when you hear of some outrage, that the main question for this embassy is trade and not politics. I feel as sorry as you do about the way these people treat strikers. Or Jews. Or political prisoners. But we've got to keep our priorities straight. They're moving ahead, in some ways they're moving ahead fast, and trade helps Russia to make progress, in many ways. And please keep in mind that trade is good for us. Which, I would emphasize, is the main reason we're here."

"I know, Angus, I know. But ghastly things are going on here..." He went back to his office, still angry. Weed's wife Oksana, he had learned, was half-Russian. Was she leading her husband to take a benevolent view of this damned country? There might be little he could do change the boss's mind. Perhaps best not to keep after Weed, but he didn't like what he was seeing in Russia.

Carver found that there was a lot of American business interest. Every week brought some new American investor to the embassy, as well as return visits from people like Charles Crane the plumbing manufacturer, who had interests in Russia—a power company—quite separate from the great Crane works in Chicago. Crane told Carver, though, that he was reluctant to increase his involvement in Russia any further. He had visited the country a number of times, and he was far from confident about Russia's future—and not just Russia's. Crane had a Czech friend, a professor in Prague whom he had gotten to lecture at the University of Chicago, and who knew more about Europe than anyone else he had ever met. This Masaryk had told Crane recently he was convinced Europe was moving toward a great new war.

After August, autumn came on fast. The days grew shorter, colder. Carver made a number of new acquaintances. Russians seemed to like Americans. More than once, people whom he met told Carver that Americans had a wide-open nature that was like their own. Maybe so, but there was more to it than that. He kept reminding himself of that old saying, "Scratch a Russian and you'll find a Tatar." They are certainly not Yankees. Hardly even Europeans, he thought.

One Thursday evening he went to an elegant dinner at the palace of Prince Smirnovsky, a senior counselor in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They seated him between a pleasant old princess whose French was far better than his and an attractive lady of perhaps 30 who had gray eyes. His Russian was still poor, but the younger lady spoke good English. Her name was Anna Pavlovna von Mohren, and she pointed out her husband, Dmitry Mikhailovich, seated across the table.

The husband had a square black mustache set in a face that looked almost cruel. He was, his wife said, vice president of Astoria Eastern, the big trading company. The two of them had a chateau in Livonia. Perhaps sometime Mr. Carver might like to come for a weekend. After they rose from the table, Dmitry Mikhailovich von Mohren agreed with his wife; Carver must certainly come to them.

The next evening he went to another dinner, this one given by the first secretary of the German embassy, Schmid, who had told Carver earlier that he was much involved with the intellectual world of the Russian capital. His guests seemed to include more artists than officials or princesses. One guest was a young man named Bugaev who spoke passable English.

Bugaev told Carver he was a writer, a poet, and belonged to the Symbolists. He wrote under the name of Andrei Bely.

"Symbolists? What's that?"

"Ah," said Bugaev, "Symbolism began in France. You know Charles Baudelaire? We want, how to say, fluidity. Imagination. My Symbolist friends and I are eradicating boundary between arts. Just now I am completing novel about Petersburg. If you should read it, you could probably think it is, how to say, grotesque. My main character is this city, itself, in all his beauty and horror... you have seen some of this horror that lies around us?"

"Well," said Carver, "I have certainly seen the beauty. It is a remarkable place..."

Bugaev interrupted him. "Very diplomatic. But next time you have morning free, go out to Kolpino. K-o-l-p-i-n-o. Go there and then you can decide on beauty..."

The next day was Saturday. It was a foul day. It was only the middle of October, but the leaves were off the trees. The sky was dull gray. A thin, cold rain began to fall, and it turned to wet snow as he walked south through the city to the Nicholas station. It took half an hour for the suburban train to reach Kolpino. Kolpino, he found as he walked away from the station, was mills and belching chimneys, huge slag heaps, cinders underfoot, shabby old men on the street. Bogov, or whatever his name was, had told him that the country was heading toward disaster, toward a new kind of hell. He could believe it. Kolpino looked like a kind of hell right now, a frigid hell. A drunk, a young man wearing no coat but only a dirty undershirt, was staggering toward him in the cold. He turned back toward the station. Ten minutes was enough of Kolpino. It was far worse than what he had heard from Ivanich the usher.

One of Major Lomov's sergeants had followed Carver to Kolpino. The major had been wondering whether this new American might be some sort of spy. No, thought the sergeant walking through the dirty snow, just a damned fool.

Two weeks later Anna and Dmitry von Mohren invited Carver to Livonia for a weekend. He had been wondering what sort of a region Livonia was, and it was only an overnight trip from St. Petersburg. He had read that the Estonians, who inhabited much of the place, spoke a language like Finnish. Livonia had been conquered by the Teutonic knights centuries ago, and later by the Swedes. It had been part of the Russian empire for a century now. That almost exhausted his knowledge of Livonia and the Estonians—but not quite.

A few days before he left for his weekend with Anna and Dmitry, Ivanich brought up to Carver the calling card of someone named Gustav Suits, who was asking to see the second secretary of embassy. Suits? That didn't sound Russian.

"You wish to see him, Your Honor? He speaks English," said the usher. Why not, thought Carver; must be a businessman.

Gustav Suits turned out to be an Estonian, aged around 30, no businessman but, he told Carver, a poet well known in Estonia and the founder of the Young Estonia movement.

"You said Young Estonia? Do explain."

"Gladly. You must know that Giuseppe Mazzini, the republican, founded a movement that he named Young Italy, decades ago. This was copied in other countries. There is, or once was, a Young Hungary, a Young Ireland, and so on. What these movements have had in common is the aim of creating modern nations. What we want for Estonia is progress and education and prosperity. We are under the Russians, but we are not Russians. We are part of the Russian guberniya of Livonia, but Estonians are a separate nation, a Western nation. We number almost a million people. And we are, what's the word, tough. We resisted becoming Christian until the Middle Ages, and most recently we have been resisting the efforts of this Tsar to Russify us. When you come to Tallinn, which the Russians call Reval, you will find it a fine city. Our new National Theater, just completed, is as grand as anything here in Petersburg. We are becoming a cultured, modern people.

"We want the Americans to know about us, and that, sir, is why I came to call on you. There are not too many Estonians in the United States, I think maybe just ten thousand or so, but my cousins in Chicago tell me they have a good reputation. That's what we want, a good reputation. Someday, God knows when, we will have a chance at independence—and we'll hope for American support."

Carver thanked Suits for his visit and drafted a brief dispatch to the Department, which he knew Weed would sign and send and Alvey Adee would read with a frown. Mr. Adee did not want to see a fragmented Europe.

A blond and slant-eyed, middle-aged Estonian driver in an old blue topcoat with brass buttons met Carver at the station in Reval, at 7:00 AM on Saturday when he got off the first-class sleeping car on the overnight express from St. Petersburg. The driver was named Tavi, and that was all that Carver understood of what he said. The car was an elegant, late-model red Opel convertible. The roof was up, and there were isinglass windows, not much good for viewing the countryside. He explained to the driver by signs that he would sit next to him in the front, with the roof up, but he wanted the side window down so he could see. And so they started off.

It was November now, and in the open car he was glad to be wearing an overcoat and a fur hat, but he didn't want the window up, he wanted to see. Reval had fine buildings. He looked for and spotted the amazing Gothic spire of the church of St. Olav. He had read in Baedeker that it was 456 feet high, the highest of any church in the Russian empire. As they drove out of the little Hanseatic city, he could see the ground was frozen. There was white rime on the bare limbs of the trees lining both sides of the road.

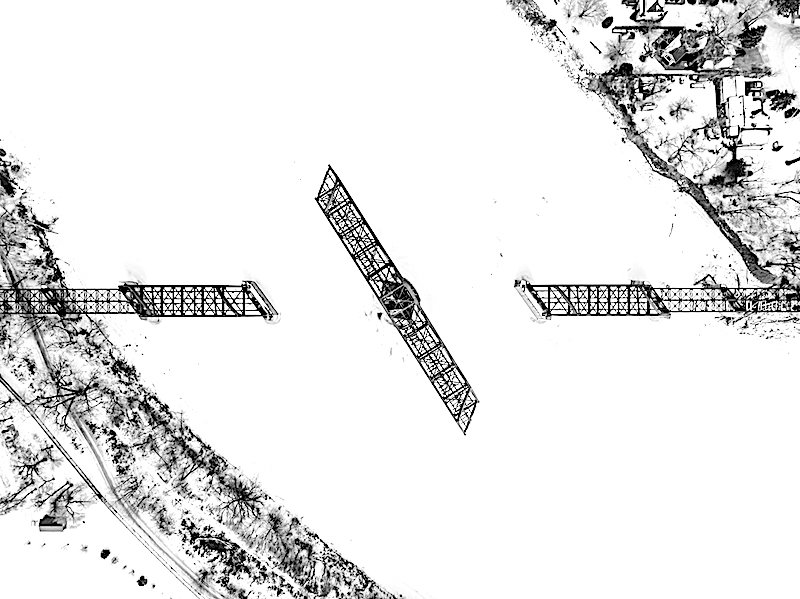

They drove south for over an hour past fields and forests, small villages each with a towered Lutheran church, sturdy single farmhouses set on forest edges. The sun came up in a clear sky on the left, but it stayed cold. The rime on the trees glistened but did not melt. Here now was another village, then a stone bridge across a little river, and beyond the bridge sat the von Mohren chateau, protected by the river that almost circled it. It was also protected by a big stone wall, and there was a round tower. More of a castle than a chateau, he thought.

They drove through a gate into a courtyard paved with large flat stones. Anna Pavlovna was there to greet him in a blue wool jacket and blue skirt. She was very pretty.

Dmitry Mikhailovich had asked Carver to come on the previous day, Friday, so he could join the hunting party that was to ride out very early on Saturday. But Carver could not; the weekly courier left St. Petersburg each Friday evening with the diplomatic pouch for Washington, so Friday was always a busy day in the embassy as Carver and Weed completed a week's dispatches. Besides, though he liked horses, he was no hunter. Nor had he fancied spending what would probably be a month's pay or more to outfit himself for one morning chasing wild boar.

Anna led him into a great hall, dim after the sunlit courtyard. The hall had a raftered ceiling that must have been a good 40 feet above the floor. Halfway up, a balcony ran around three sides of the hall. A maid took his bag and led him upstairs and along the balcony to his room. There was a smell to the room; not a bad smell—it just smelled old. A big window looked westward over miles of forest. He took in the view, and the thought came to him that other men had stood at this same window four or five hundred years ago, and had seen this same scene. Eternal Russia—but then Livonia was not exactly Russia. I'm not quite sure what it is, he thought.

Anna Pavlovna von Mohren and Stearns Carver drank coffee in a warm sitting room off the hall. For some minutes she talked about dinners and people in St. Petersburg. He was lonely for a woman. She smiled at him. He could smell her faint sweet perfume. She proposed they take a walk in the forest until the hunters should come back. "After they come, we shall have much drinking and eating, so perhaps now is a good time to show you our place, to take some air."

Carver looked at this pretty woman longingly. He had gone, one recent Saturday evening, to Chez Misha and paid 50 rubles for a quarter-hour with a big-breasted blonde named Lyubov. The following Monday, Charlie Weed had mentioned hearing that two-thirds of St. Petersburg prostitutes had syphilis; so, Carver thought, he'd best not do that again.

They walked into the Livonian forest, down a little road through a woods of pines, birches, occasional big oaks. It was less sunny now, clouds gathering. She took his arm and told him that she had grown up in Moscow. She had had an English governess. "But," she added, "As you have heard, Dmitry's English is better than mine. He was two years at an English public school, and he goes frequently to London on business. He has been to New York City, and even Chicago and San Francisco."

"Tell me about Livonia, if you will."

"Oh, this country is quite beautiful in summer. I like it less this time of year. And these peasants, these Estonians, are stiff people. Is that the word, stiff? They are not like our good Orthodox peasants in Russia. They work hard, but they are... stiff. They can all read and write, yet sometimes they pretend not to understand Russian. They say they are not even peasants but Bauern, I mean farmers. Sometimes I think they are as bad as Poles. I do not think Westerners understand our empire. It is very... very diverse. We need a samoderzhavets, a man to hold the power. An autocrat, I think you say. We need our Tsar to keep our land together."

There was no wind, little sound, no animals but a squirrel or two. Then just 50 yards in front of them a great boar ran across the road. Anna's grip tightened on his arm. She looked up at him, and then she smiled.

"I am not afraid," she said. "But let us turn back now. We have been gone for an hour, and the hunters will be returning. We will tell them they missed seeing the best game."

It was near 1:00 when she and Carver returned to the chateau, to the same sitting room. They sat together on a love seat, and her gray eyes looked into his. He wanted to take her in his arms, to kiss her. But just then the hunters rode into the courtyard and she ran out to greet them. Carver followed. There were 15 men on horseback plus three riderless horses. One of the riderless horses carried a dead boar, another the body of a large gray wolf.

Four of the riders quickly dismounted. From their rough clothing they were clearly peasants, attendants. They held the reins now while Dmitry von Mohren and his ten guests dismounted. All 11 hunters were resplendent in leather jackets, tight riding pants, fine boots, polished spurs.

Von Mohren kissed his wife, then greeted Carver warmly and introduced him around. The other hunters were apparently all Russians, though one or two names sounded German, no doubt Baltic barons like their host. They were noisy. Carver guessed they had been at their flasks on the way back.

Von Mohren waved the party toward the entrance to his great hall. Then he turned to Carver and said in his perfect English, "We are not altogether happy, Stearns... I may call you Stearns? We got one boar, as you see, but the very king of the boars escaped us in the forest. I got off one shot. I think I may have nicked him. Later we turned up a pair of wolves. I got the male. But... bad luck, all told. We should have done better. Come have something to eat. And to drink, by all means."

The sun had gone behind the clouds, probably for good. Inside the hall it was dimmer than before. There were just two windows, not large ones, on the south side, the side without a balcony above. But there was a fire now in the huge fireplace, and there were candelabra on the long table in the center of the hall which was otherwise loaded with platters, casseroles, carafes of wine, bottles of vodka.

Over the next two hours, as it slowly turned dark outside, the hunters in the hall gorged themselves on food and drink. Anna Pavlovna appeared from time to time, supervising serving girls who brought in new platters and casseroles—and carafes—for the hunters; it was entirely a men's affair.

Carver did not want to gorge himself, did not want to get drunk, but several of the hunters insisted he drink with them and he downed a good amount of vodka. After a while he thought, how long can this go on?

Two members of the group were getting especially drunk. One of them was the brother of Smirnovsky from the foreign ministry. The brother kept telling Carver what two great nations the Russians and Americans were. They should be friends and close allies, and now they must drink to friendship. He poured full glasses of vodka for himself and Carver. They drank. "Do dna!" the Russian insisted. Down the hatch.

The other notable drunk—God, they were all drunk!—broke in as Carver finished, with a shiver, his latest glass. This other type was a black-bearded burly fellow named Lavrov. The hunt had gone badly, Lavrov said. It was the fault of the local people, who did not like Russians. "People use witch... you say witch? Ah, witchcraft. Koldovstvo. They use witchcraft. Today we get one boar. Only one boar. Witchcraft!"

Lavrov stopped and looked up. Carver looked up, too, and saw in the growing dimness above them a ghostly white apparition moving along the balcony. What could it be?

Lavrov shouted, "Koldovstvo!" Carver saw the man pull a pistol from his pocket and fire three quick shots at the white mass above them. The mass fell behind the railing. It was a servant girl carrying bed linen. For a moment there was no sound in the hall. Von Mohren said, "Bozhe moi!" and ran for the stairs. But the girl was dead.

The party was over. An hour later he was on his way to the evening train in Reval with Tavi, the driver in the coat with brass buttons. Tavi spoke, not really to Carver but to himself, in Estonian, on and on, as they drove through the dark cold country. Whatever he was saying, there was tragedy—and rage—in his voice.

The following Wednesday, he once again saw the von Mohrens at dinner, this time at the house of a Princess Ladogina. The girl's death had been reported to the police, but they had not charged Lavrov. "It was only an accident, only a peasant, you know," Anna Pavlovna told him. He looked into her gray eyes and thought to himself, There is really nothing good here.

Liliya reported to Lomov that Carver's mood had changed: he said little to her and was ill-tempered. Nor did she find much else to report about him. But that mattered little. Far more important was Lomov's access to the American embassy's reporting to Washington, from another source—Oksana Weed.

Oksana's father, a New York businessman, had met and married her mother in Russia years earlier, and they had soon gone to America. Four decades later at a St. Petersburg dinner, Oksana Weed, the spouse of an American diplomat, met a handsome officer in a finely tailored uniform who introduced himself as Lomov. He called on her the next day, and after two minutes of pleasantries, he quietly made clear to her that her 22-year-old cousin Nastasya Danilova, exiled to Siberia as a suspected revolutionary, was going to suffer if Oksana did not help what Lomov called her homeland.

Oksana, born in Bronxville, had never felt herself Russian, nor had she ever known Nastasya, but she had heard about her exile while the Weeds were still in Washington. Her little cousin's fate had utterly convinced Oksana that Tsarism was evil. When she and Angus moved to St. Petersburg, she was glad that as an American diplomat's wife, she was free from this evil regime's clutches. Now she realized she was not.

On evenings when the Weeds dined at home, Angus always took the dog for a long walk along the Neva after dinner. Oksana would go into his briefcase then and, some evenings, would find and quickly copy for Lomov the draft of an embassy dispatch. After several months of this, Lomov thanked her; Nastasya might have her exile shortened.

Neither Weed nor Carver ever learned that the embassy's reporting had been compromised. Did it matter? What Lomov and his superiors learned was unsurprising: the Americans found Russia's regime corrupt and cruel, but for commercial reasons their embassy put a high value on the bilateral relationship.

This world soon changed. In 1914 the Great War erupted and soon was killing millions. Carver was happy to leave St. Petersburg, now renamed Petrograd, in 1916, on transfer to Madrid as first secretary of embassy. He traveled south to Odessa to avoid the battlefields and sailed safely to Barcelona on a small Spanish-flag ship. (Spain was staying neutral.) In Madrid he found himself deputy to an ambassador named Joseph Willard, a Virginia politician who had learned little about Spain in his several years there and was happy to let Carver do most of the work.

Angus and Oksana Weed left, too, taking the Trans-Siberian railroad east to Vladivostok en route to Santiago, Chile, where Angus was again to be the number-two. It was no promotion. Alvey Adee had long suspected Weed's reporting from Russia was too rosy, and events had proven it to be so.

In February 1917, revolution in Russia knocked out a Tsar ever more divorced from reality and tore apart his suffering empire. In October, Lenin took power and launched a new despotism. Gustav Suits and his compatriots pushed for the independence of war-torn Estonia, and soon, in the wake of the war, the little country and its neighbors Latvia and Lithuania were proud although ravaged new republics. Meanwhile the von Mohrens, Carver heard, had made their way to London, where Dmitry joined a bank and was again prospering.

Lomov the loyal Tsarist officer declared himself a Communist and joined the Soviet successor to the Okhrana, the Cheka, in April 1918. That same month, five thousand miles to the east, Oksana's young cousin Nastasya died of starvation in a village on the frozen River Lena. But Carver never knew anything of either the policeman or his prey.

In Madrid Carver liked to stroll, Sunday mornings, along the Paseo de la Argentina in the Buen Retiro park. See him there one Sunday in the sun, thinking back to Russia. He would always remember the strikers and cruel Cossacks, the foppish princes and angry intellectuals, the exotic smells and sounds of Petersburg, the grim onset of winter and the cold hell of Kolpino, the late flowering of Russian spring and the summer that was sweet but too short, the von Mohrens in their castle and contentment—and the rage of the Estonian.

He looked down the broad walk lined by marble statues of cruel and haughty kings. He thought, I'm no Red, but these kings and emperors are no damned good. And Lenin and his sort are worse. Ye gods, is there no justice in the world? Where's the Queen of Hearts? Off with their heads! Off with all their damned heads!

But the gods were deaf and the Queen was nowhere to be seen. And it was time for a coffee.