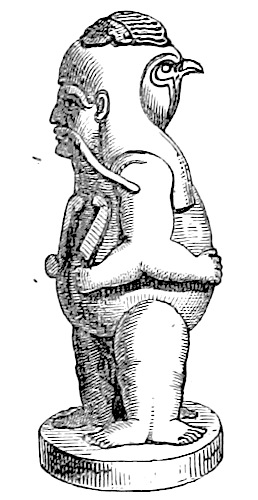

Image courtesy of The British Library photostream

Maude's Diner on Halsey Street on a rainy Brooklyn night, the smell of fried eggs and hash browns conflating with the musky sweat of the cook droning along with Patti Smith on the jukebox—Jesus died for somebody's sins, but not mine. He's a strapping young man, the cook, dressed in white pants a size too small, the bulge in front—package, we used to call such an exhibition—as obvious as a bootie call. I watch him stretch strips of bacon across the griddle and wonder what egregious sin he committed for Jesus to deny him. He's old enough for redemption, young enough to think he doesn't need it.

The waitress could be his mother, the type who scoffs at the Dirty White Boy tattoo on his bicep and prods him to join the Army—make a real man out of you, she probably carps at Sunday dinners, his father nodding fervently in agreement. I'd tell him it doesn't take a buzz cut and AK-47s to be a man. Ambiguity works just as well.

Except for the three of us and the closed-faced old man who wandered in on a waterlogged whim around one a.m., the place is empty. The old man is waiting for his food. The waitress is wiping down the counter with a crusty white cloth. I'm nursing a lukewarm cup of decaf. Patti is singing about a woman named Gloria.

Oh, she looks so good, oh, she looks so fine

And I got this crazy feeling and then

I'm gonna ah-ah make her mine

Ambiguity isn't Patti's bag. I like that about her.

My husband, dead a year now, used to say I wore my moods like street signs—bridge ices before road, one way, no entry. For the life of me, I told him once, I still can't read you.

It was a lie. I just pretended it wasn't.

We were kids when we married, straight out of college— naive enough to believe love can conquer truth, foolish enough to deny truth will eventually prevail. I ignored the signs, so cleverly disguised, so meticulously sequestered. He lived in silhouette, elliptical, tangential, harnessing the light, revealing only what he chose.

The last text I sent him, the day he died, spelled out what we both finally realized I knew. The look, languid and longing, that had passed between him and the man—a boy, really—standing on the platform the night before, while we waited for the L-train to take us to the theatre, was the Rubicon, concealment laid bare in the rush of oncoming train lights. I don't remember what play we saw or whether or not we went to dinner afterward. I do recall the shoes I was wearing—my black leather ankle boots, scuffed and worn. He shined them for me the next morning. Then he left—first the apartment, then the planet. I threw the shoes into the Hudson after a homeless man fished him out.

The cook hands a steaming plate of food to the waitress. She shuffles over to the old man and sets it in front of him. The gesture is rote, spiritless. She's been doing this too long. The old man tucks a paper napkin in his shirt. He doesn't look at her. He doesn't speak to her. He's been living too long. Sometimes people do. You can see it in their eyes, that vacant stare that sees through blood and bone, wood and steel, fire and water. They know there's nothing in the innards worth mentioning.

The cook checks his cell phone and grins. His front tooth is chipped. He's still handsome, though. He won't be in time, but for now he's reveling in it. I can tell by the way he cocks his hip while he texts, the way he runs his fingers through his wavy hair when he's done.

The waitress admonishes him—You got time to lean, you got time to clean. Her voice is raspy and thick. She's a smoker. I can smell the evidence whenever she walks by. Her floral perfume doesn't mask the stench of Marlboros on her tan uniform or in her graying hair. I know the stench of Marlboros. My husband smoked them. Those things'll kill you, I used to tell him. They didn't. He beat them to the punch at thirty-two.

The cook stuffs his cell phone in his pocket. I wonder if he's stuffed anything else in it but decide he isn't the type. His is a body politic, physicality incarnate—tangible, earthy, solid. I doubt he feels the need for camouflage. I envy the woman on the receiving end of his text. (I assume it's a woman. I could be wrong. I've been wrong before.) I can imagine the frankness of his words, the overtness of his message.

My last text to my husband was just as frank. I remember typing the letters, hearing the whoosh when I sent the message, realizing everything had changed with just three words.

I see you.

The waitress refills my mug, fishes two packets of sugar from her apron. She knows how I take my coffee. I go there a lot, usually on her shift, the cook's too. I like familiarity, certainty, both of which are scarce. I reach into my purse for my wallet. My hands are trembling. I've been awake for days, maybe longer. I don't remember the last time I closed my eyes. The waitress squints at me over the rim of her bifocals. On the house, she says. I stiffen. She thinks I'm strung out, I sense, maybe even homeless, unhinged, forsaken like Patti, like the cook and the old man, like her. You don't know me, I want to tell her. You see what you want to see. I can pay, I say. She shakes her head. On the house tonight.

Patti is pining for Gloria. Then there's silence, a brief interlude of nothingness—space and time and sound sucked into a black hole and the four of us along with it. I'm anticipating the next song, the jolt of an electric guitar, the violence of a snare drum. When it comes I don't recognize it.

I glance at my cell phone, the last text I sent my husband. He never responded. I don't even know if he read it. But he knew I knew.

I still text him sometimes, always here, at Maude's Diner on desperate sleepless nights, music playing on the jukebox. The first time it was Led Zeppelin—“Black Dog.”

Hey, hey, mama, said the way you move.

Robert Plant's voice—unmistakable, primal.

With eyes that shine, burnin' red, dreams of you all through my head.

Ambiguity isn't Robert's bag either.

The ding came near the end of the song. The cook checked his phone. He thought the ding belonged to him. I waited for the silence. Then I looked, flustered by my husband's name on the screen. I still have his name. Someone else has his number.

I read the message.

Who is this?

There was mystery in its frankness, camouflage in the camouflage. I read it again, savored the syllables, the spaces in between. Then I typed three words, the same ones I type now—stark, guileless, artless.

Please forgive me.