|

|

| Jul/Aug 2019 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Jul/Aug 2019 • Nonfiction |

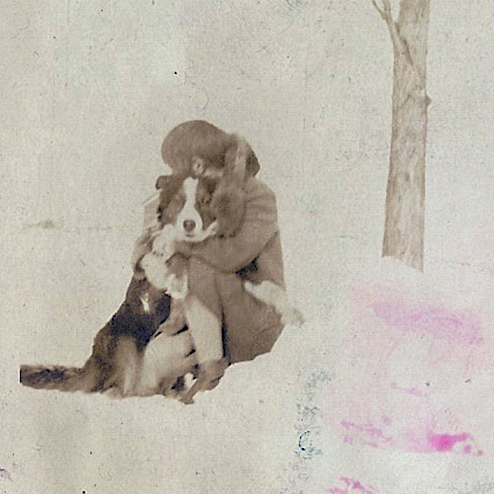

Pal and Shirley, 1929

"Thus, do we live, forever taking leave." —Rilke

After 12 years, I still fail to understand the looks you give me, the sounds and movements you make. Your signs. I see you studying mine. As the one with less power, you are a better reader of me than I am of you. You want to please, but you want your difference too. We remain strangers at a borderline, engaged in continual acts of translation. I don't want this command over you. I don't seek fusion with you.

Yesterday, out for our usual walk, you stopped and stared at me. Frozen, you reminded me of playing statues as a child, except there was unhappiness in your eyes. Your body, normally a yes to walking, had startled us both with a no. You advanced a few paces. Stalled again. This was the rhythm until we made it home. Yet today, you bounded down the bank and paddled in the stream. Back up the bank, shaking water from your coat. I look for patterns and find only these. Yes days and No days. Days of motion, days when the limp returns. Yesterday, I was poised to ring the vet. Today, you disappeared into the woods in pursuit of a rustling in the undergrowth. I used to worry about losing you in there. Most of the time now I just wait, lost in my own thoughts, until you re-appear somewhere along the path.

But these shifts in your energy unbalance me. I fear failing to spot changes that you would wish me to know. I run my fingers over your bumps when I brush you, press my cheek against your soft cheek, just above your whiskers; I inspect the leathery pads of your feet. I want to be a better person and you are the measure of me.

Name

You were ten weeks old when you came to us. We said you had something of the "old soul" about you. There is a line by Mr. Dylan: Is it because you remind me of something that used to be / Something that crossed over from another century? Ever the stranded historian, I felt that about you. I wondered if Pal, my mother's girlhood Collie, might have come to nestle inside you or rove as a ghost in our house.

Of course I never knew Pal. I could never know the person my mother was when she hugged Pal on a snowbank in 1929. I miss the mother I knew, but the one I never knew, I miss more. Is this why I imagined that her dog had slipped into the next century? To remind me that Mom had a name, Shirley, and a life before me? That before marriage and motherhood, she lived in farm country and loved a dog? Or maybe it was simpler than that; maybe Pal had come not for me, but for you. If I draw from the dead ones in order to feel less forlorn in a new situation, why wouldn't you? Pal might help you in the same way, soften the blow that you had not found a home, but lost one, and we were strangers to you. Your own mother was gone and we were not dogs.

So I gave you an old-fashioned name from the era of Shirley and Pal. I looked on lists of names popular in the 1920s and found Agnes. It was only after I chose it that I remembered the third sister in Meet Me in St Louis was named Agnes Smith and based on the writer of the tale. I confess that it pleased me to project my affection for Dylan, Mom's dog, and an old Judy Garland movie onto our puppy. Such burdens we humans place on the lives that cross ours! I am grateful now that you were unaware of it all. None of this mattered to you. What mattered is that Agnes was a sound that joined you to R, Isaac and me, and within days, you were responding to it.

Dancer

From the beginning (and this has persisted these 12 years), I saw compounded fear and bravery in your face. You were frightened of new people or situations, but not of your own powers. You were an upright and determined retriever puppy, blessed with sturdy legs. I look at early photos of you and realize that your legs were, to borrow a human vanity expression, your best feature. You stood straight as a dancer. You were a bounding Nureyev. Soon your legs were longer and slimmer, but no less striking. As you grew older, you developed a love of having your front legs stroked. Nowadays, you like to lie on your stomach and stretch those dancer limbs flat in front of you so that I can run my fingers up and down them. If I pause, you place your paw on my hand to urge me to continue. Don't stop, Amy.

I remember when you were young and your joints were not sore. Where does time go—this, in my country, is not so much a question as a lament. You didn't know me when I was a girl, when Shirley was my mother and Pal was gone. I was a dancer too, with springs in my legs. From age five to 15, my mother drove me several times a week to ballet school. I was intensely attached to her and this was time together. But as I reached adolescence, I lost interest in dance lessons and in her. During our car trips, we began a series of arguments that would last years. Unlike you Agnes, I was afraid of my powers though I believe I was fighting for them. Yet for the rest of her life, my mother missed the daughter who was once sweet and biddable, and who pirouetted in leotards and floaty costumes.

Naming

I did not know it at the time, but R disliked your name. He didn't tell me until months later when you went missing during a walk outside Cambridge and I began calling loudly for you. He took me by surprise, but in the next moment, I burned like a reprimanded child. I don't know why it bothered me so much but thereafter, I blocked his opinion with the thought that if he did not like your name, he should have said so at the beginning.

We had lately given up vocalizing much disagreement, as there was a cumulative anger between us, a wear-and-tear-of-family-life anger that made my stomach churn. Internally, I could supply both sides of any dispute and award myself the last word. I suppose he was doing the same. I realize now that I had already lost my marriage, at least the remembered one of youthful pleasure and adventure. Thirty years was a long time. I began to avoid a husband who had grown unhappy and found fault with me frequently and for reasons I could not anticipate. When a person tells you off for putting the salt shaker back in the wrong place, I guess it's safe to say that something important is not being said. When your response to the salt shaker incident is to sulk rather than argue or laugh it away, something important is not being said. Love was not in the room. The days of not caring about salt shakers were gone. I was not ready to face the changes between us, so I was, during the period of your arrival, ducking open hostilities and perhaps hoping that you might mend us. I am sorry for that now, Agnes, sorry that we brought you into a vanishing family and burdened you with sadness. Sorry I did not speak to R and he did not speak to me. Sorry we didn't try.

It's odd to think that my life with R started with so much talk between us, turned silent in our last year or so, and then the day he left, I began talking again. To beat the band. But he was no longer there to hear it.

Forgiveness

I am sentenced to that place some call the "prison house of language" and through its bars, I see you out there. I want to explain what happened, how things fell apart. Ask the forgiveness you already grant me without knowing what forgiveness is or why humans crave it.

Dozens of times each day, you reset matters between us, release me from blame for an error in the moment just gone, invest hope in the moment newly arriving. Shall we go out now, Amy? My need to go out is here; it's now. I don't dwell on your failure to see this ten minutes ago. You humans like to dwell, and it does not make you happy.

Or to take another recurring negotiation. Amy, might I lie on the sofa this time? The times you say no don't matter. I forgive you; I untether you from your previous interdictions so that you might say yes in the new time. In my country, we're constantly renewing the situation, we're triers; we try and try, without concern for what went before. I do know memory, Amy. Memory is there, but it does not govern me. Shall we walk now?

Memory

Agnes, you are right about humans and memory. Take my own case. I dwell, as you put it. I deal in verb tenses. I'm a breathing scrapbook, compulsive archivist and memorialiser. Holder of grief and grudges, reluctant denizen of the present. History was my subject, but you don't care.

I wonder if for you, the past is mostly recent, a time-lapse blur of light or smell as you trot alongside me. Olfactory flurries, a wish or opportunity carried on the breeze that lives longer than a second, causes you to raise your head and exercise your nostrils, then dies, making way for the next one. Or there is a whiff from a few feet back that turns you on your tracks. Did we just pass a blackened banana peel by the side of the path? Perhaps lived temporality, to you, is a loud smell of slightly longer duration.

But then in currents beneath the surface, it must be some older memory of my much-repeated displeasure (don't eat that rotting thing, Agnes) that makes you pause and challenge me eye to eye, before darting back for the banana peel. So perhaps memory is the recognition of a prior smell or prize or refusal. Yes to this; no to that. Life-long associations to particular words or phrases: time for a walk, are you hungry, dozens more. But what else do you remember? What matters to you?

Where does longer memory go in you, Agnes? Does it seep and hold you captive and make you weep inwardly, as it does to me? Mostly, I think not. But when I say Isaac's name and you raise your head and glance in every direction, not knowing that he is in America, you are in England and there is an ocean, something stirs in you. You are looking for him. He went only months ago. Then comes my prick of guilt. Have I brought grief with the sound of his name? Am I making you suffer again, something you suffered for many months, no years, after R left? How many times were you forced to learn that the utterance of a name does not bring the person? But that is another story, Agnes.

I find it hard to speak of R, even now. But Isaac is our son; and we sometimes spoke as though he were your elder brother. I know, I know. Family is a burdensome construct in my country. I wish you could tell me about dog kinship because I dislike our human narratives of canine hierarchy and dominance that have lined the pockets of trainers and made power the key to dog-human relations. Of course family, for us, is not without struggles for power. I learned that lesson in childhood, then again in marriage. But nowadays, I think of family as a sad, fractured thing because sooner or later, one way or another, whether by death, migration, or just plain not getting along, it falls apart. Yet even as we howl at its ravages, we humans cannot seem to stop longing for family the way travellers in a snowstorm long for the hearth. I know I do.

I've wandered off topic the way you wander off footpaths, Agnes. Too many banana peels in our story. I am frightened of slipping on every one, failing to write the two of us before it's too late. Where were we? I was wondering if you miss Isaac. Here is what I wanted to say about Isaac and you. It's painful that I cannot explain to you where he is, why he has gone, what the chances are he'll return while you are alive. Again, constructs of my country. To you, there is Isaac and there is not-Isaac. Isaac is better than not-Isaac. Therefore, it's easier for you not to hear his name, because in your country, a name is uttered when it is accompanied by presence or imminence. So when I say Isaac, it means here-is-Isaac. And this is why you immediately hope for him.

Some memory relating to Isaac runs through all this, but can we say more? Can we say, for example, that you recall his face, voice, or smell? Agnes, you know sensory experience better than I. It is you who should be answering now. Where are you? I lift my eyes from the keyboard and see you are asleep on your mat, a half-chewed bone placed neatly by your front paws. If I take out an old tee shirt belonging to Isaac, and you wake, bury your nose in it and lick it, will this be something akin to a Proustian moment, your madeleine? Agnes, I wish you could know that among Proust's love letters to the composer Reynaldo Hahn, there is one to Hahn's dog, Zadig.

Zadig, you not read, and you have not ideas. And you must be very unhappy when you feel sad... But know this, my good little Zadig... I have been a man and you haven't. Human intellect only serves to replace those impressions that make you (Zadig) love and suffer with weak facsimiles that cause less sorrow and give less affection. In the rare moments when I recover all my affection, all my suffering, I no longer feel through these false ideas but rather through something that is similar in you and in me, my little dog. And this seems to me so superior to all the rest that it is only when I have reverted to the state of dog, to a poor Zadig like you, that I start to write.

This is my missive to you, Agnes, my debt. So, let me return to you and Isaac. Might we draw on the "weak facsimiles" however inadequate, and say that you miss Isaac? I suppose so, if language from my country must be imposed in order for me to talk to myself. You don't understand my words when I ask if you miss Isaac. There is no explanation to a dog when a person leaves and does not return. You don't understand my impulse to narrate you. You let me babble, let it wash over you, the familiar music of my voice and the tapping of my keyboard. But yes, I believe you experience longing for the absent ones. It is not like my longing, and we can never know how it differs. But there is something there, when Isaac is not there.

I saw memory

The response you once reserved for the sound of R's name, head up, scanning the room, listening for the door, puzzled look in your eyes when he did not appear—the look you now show at the mention of Isaac—this has gone. I watched it recede over the course of two or three years until finally, R's name brought little to no response. That was how long it took. Throughout that period, I sometimes tried his name out loud to see if you reacted. You would begin looking for him and I felt ashamed of my cruelty. But I could not stop myself doing it from time to time. I wanted to believe you had forgotten him. I wanted to forget him.

Then only a few months ago in preparation to move to a new flat, I went through our old family boxes and pulled out the few items R had left behind. Some letters and notebooks that had got mixed in with my own. A few maps and books left on the shelves when he moved out. I put them in a separate box and he came to collect it. I see R once in a while but you, Agnes, had not seen him for nearly five years. When he walked in, it was as though five years of dog memory and dog grief struck the house like a tornado. You showed emotion I am not allowed to show, did things I am not allowed to do. You nearly knocked him over with your jumping, yelping, hyperventilating, mad licking of his hands and face. You repeatedly grabbed his sleeve with your teeth. Were you hoping to make him stay?

After he drove away with his last box, you could not settle. You sniffed every inch of floor where his foot had fallen then finally, whimpering low, curled up beneath our old kitchen table. I sat down on the floor near you, my back resting against the cupboard doors. "I'm sorry, Agnes," I said. You rested your head on your paws, watched me for a while, and then your eyes closed.

Talk

To go back further. The day R left for good, I went to the corner store and bought a bottle and a pack of Marlboros. I hadn't had a cigarette in years, but I spent that night pacing the kitchen floor, drinking red wine and chain smoking. I cried and talked to myself, first in despair, then rage, then back to despair. This was the beginning of many months during which I talked aloud to spaces without people. My thoughts, previously held in reserve, began bursting from my mouth. I argued with my absent husband, argued with myself. I described the mess I was in. I talked to the rooms and the pictures on our walls; I talked to supermarket shelves, to trees and footpaths where I walked you each day. You were there, Agnes. I wasn't talking to you, but you were a witness. I might leave the house talking, go to work and shut up long enough to achieve coherence in front of my lovely undergraduate students, only to come back hours later, ranting again. You waited there, gifting me silence I could not receive, showing me silence I could not perform. I failed to see how we might be vulnerable together. I sensed my own vulnerability, but not yours. Yet I kept you close. You lay beside me at night, your head on R's pillow.

I can almost hear my voice again, rendered strange and throaty by cigarettes. I see the kitchen in our old apartment, a battleground now gone, now someone else's kitchen, the lost scene of my pacing. I see its map, the repeated trails that motion photography would have revealed to be layered crossings, circles, and figure eights on the floor. It's as though I am an evolved if still broken guardian angel, hovering above an earlier self. I see you too Agnes, sitting beside me, the two of us fading beneath dustings of grief and time.

The days will not be stopped

I still ask myself what I might have done differently. I know this is strange to you. You do not have a human's inflated sense of command over life. You possess agency in the moment. You choose whether or not to come when I call. You practice the politics of refusal. But life as a span of volition, chain of decisions, something planned, this is alien to you.

Despite this difference between us, you are generous. You watch over me during my times of regret, draw me to your warm body and breaths. If I am agitated, you lick my hands and face with more urgency and I have learned to let you. Rhoda Lerman wrote of her Newfoundland, "It isn't easy to let her lick my face, but it is her language and I must listen or she will stop speaking to me." Other times, you stop licking to study my face, your eyes steady. Although you hold your space, you allow me to wrap my arms around your neck and bury myself in your coat. Because you hold your space, more than that, your unknowability, you teach me separation. You hear my fevered words without their meanings and this, perhaps, is what makes you a good confessor. Your ministrations are dependent not on my words or what they signify, but your silence. Soon I let go of the impulse to talk, as you pull me to a merciful present and sit with me there. I make peace with loss and failure. It doesn't last. We will do it again. I've lost count, Agnes, of how often you have done this for me.

The days will not be stopped. Even in this now-time you create for me, we age. It's an old tale that there are seven human years for each dog year, but if we take it as a working formula, then when you turned nine, you and I were—for one year only—the same age of 63. Now, in years, you are leaving me behind, but we have each had a diagnosis or two. Mine have been minor, mostly related to acid reflux. I like to joke that I swallowed too many lies. But now, they say my heart is racing and there will be tests. You have worsening joint problems in your hind legs. Lately, one front leg has stiffened. There are lumps that we believe are fatty benign ones, though the vet aspirates them to ease my mind.

Last year you had an ear infection. It was this last, most treatable of your ailments that gave me a fright. In mid-walk, you dropped to the ground. Visibly dazed, you could not stand. I knelt beside you and coaxed you as my throat tightened with fear. I phoned the vet. For ten minutes, I waited by your side, then finally you stood and walked with me to the surgery. Slow and unsteady. The vet found the ear infection and determined that it had given you a dizzy spell. You recovered. I am too accustomed to your recovering.

"I love this tiny life which deems itself eternal," wrote Marie Bonaparte of Topsy, her beloved chow. But Bonaparte was disturbed by Topsy's innocence of death and more specifically, by the question of who would go first: Marie or Topsy. She imagined the possible outcomes.

I recognize this disturbance. It is something you dogs do to us. We find too painful the thought of your never understanding our disappearance. Without the possibility—so prized by humans—of explanation, an orphaned dog seems more lost than an orphaned child. Think of Edwin Landseer's The Poor Dog. The Shepherd's Grave (1829) and The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner (1837).

Yes, Landseer painted during the period of Victorian sentimentality laced with a fascination for death and mourning. But who can gaze at these works and not worry about the incomprehension and loneliness of her own dog?

In analysis with Freud, Bonaparte divulged that she sometimes wished Topsy already dead. Freud replied that her fervent love of Topsy was, like any extreme emotion, something that could cause ambivalence, even a desire to rid oneself of the loved object. Additionally, Bonaparte was troubled by the unbridgeable spaces between dog and woman, describing her relationship with Topsy as a painful tension (tension douloureuse). Finally, she might be killing off Topsy early, rejecting her in order to forestall the pain of the dog's death. She was ‘getting ahead' of grief, as it were.

There is another explanation we might add to these. Maybe Bonaparte saw that it is better for dog to die before human. This too, I recognize. So I write here what I do not speak aloud to you, Agnes. Although I agonize about the power of death we humans have over dogs, our casual permission to interfere with an animal's self-made death, I wish for you to die first. This is because I know that dogs wait. You wait. If I go out for a day or an evening, you wait. If I take a short holiday, leaving you with friends, you wait.

So far, trains have not crashed and boats have not sunk. I have always returned to you. Others did not return. I am the only one. This does not make me better than the others; it is just a fact of your life. It's how the chips fell for you and me. Now you are old. If I should die first, I don't want you sent to a shelter or housed with strangers, to spend your remaining days waiting for the last person who, incomprehensibly to you, is not coming back.

Maisie and Vico

In truth, Agnes, you were disadvantaged from the start. A year or so before your arrival, we lost Maisie, a black Labrador-Border Collie mix, and three months after Maisie, our cat Vico. Maisie and Vico grew up alongside Isaac, and both died as he neared adulthood.

Maisie was a skittish puppy given to jumping on strangers and nipping our heels to herd us during walks, but she outgrew these habits to become a gentle dog. I recall her warm breath on my neck when she stole between us during the night. Her heavy sighs as she gave herself to sleep. In waking hours, she was attuned to each flicker in our routines and relations. When R. and I were affectionate or playful with one another, Maisie bounded between us, her tail tapping our knees. When we bickered, she retreated to a corner, made herself small and waited for it to pass. To be alone with Maisie was to have a sensor of my moods. If I smiled, her tail made small flicks. If I sighed or muttered to myself, she was watchful. She might raise her head, the better to read me and judge our situation. I cry easily, so when tears followed some thought or memory or old movie, she climbed on top of me, a paw on each shoulder, to lick my face and remain there until sorrow passed. Maisie was goodness. A unifying presence throughout the history of our young family. Without her, we would be in greater peril.

She moved with us from Yorkshire to the Netherlands and back again, finally reaching the end of her life in York. We found walks along the River Ouse for her, but soon noticed that she was having trouble moving her bowels. An inoperable cancer. Less than two weeks later, her blockage and discomfort growing rapidly, we took her to the beach at Scarborough for a last outing. In a November chill, Maisie moved alongside Isaac, holding the rubber ring she had carried determinedly on every walk over the years. We let her do what little she wanted, stopping to stroke and encourage her. Then we drove home to York and took her to the vet the following morning. We let her go.

Vico, the toughest animal I ever knew, came before Maisie and outlasted her. He weathered not only the arrival of a dog, that dog's lumbering affection, but fights with other cats, getting lost after house moves, and becoming trapped under the floor boards of one house in an attempt to avoid moving altogether. Vico went missing so long and so often, only to return emaciated and injured, that he wore out our desire to have a cat. It was too painful. How he found his way home each time, how he managed to purr at the sight of us, even while bleeding, limping, and starving after some misadventure, we could not know.

I carry guilt about Vico that never leaves me. The source of this guilt is my attachment to Maisie. From the moment she arrived, even in her exasperating puppy days, my affections shifted from cat to dog. For years, I mostly ignored him, yet Vico never gave up on me. I was his person. He favoured me, rubbed his arched body against my legs, climbed onto my lap, and purred heavily. Agnes, it's hard to explain, but humans go through life feeling shame about particular episodes. There are things we try not to think about that, nonetheless, remain in our hearts until we die. My neglect of Vico is one of mine.

It was not until the last year of his life that I returned to Vico. As a grizzled old black cat, he developed two health problems. The first was chronic conjunctivitis which meant that he required daily eye drops until he died. The second was a brain tumour which mainly affected his movement. He walked with a tilt to one side, often twisting his head and pressing it against the wall or sides of furniture. He drank water in large quantities but did not eat much, losing weight until he reminded me of an old man. I was his nurse. We sat together in the sun on warm afternoons. Twice a day, I cleansed his eyes, and administered drops, prednisone, and painkillers. He put up no fight. Vico had always liked the sound of my voice, purring loudly when I talked to him. So I talked to him again. Told him what I was doing. What I was thinking. He purred. At the end, when the vet gave him the injection, I spoke to him and damn if he didn't surprise us all by getting to his feet one last time. He stood facing me and purring. Then he dropped back down and died.

Scarborough

In the year or so after Maisie and Vico died and before your arrival, we were an unhappy family. Isaac faced final exams; I badgered him to revise and we fought nearly every day. I was anxious and distracted. Under pressure at work and home, R was in stormy mood. During that period, our differences burst into the open. It was as though all the fault lines began to shudder at the same time, sounding a deeper estrangement.

After one particularly bad week, I took the train to Scarborough and spent a night alone in a bed and breakfast. I walked to St. Mary's churchyard to see Anne Bronte's grave, then dropped down to the beach. I thought about leaving my marriage. I thought about the Brontes, Anne's burial away from her sisters. The breaking of families. How much it frightened me to contemplate breaking ours. But mostly, I thought about Maisie and her last run on that beach. Then I returned to York and a house without its dog and cat.

Les Baux

Agnes, when people speak of first loves, these are sometimes hackneyed stories. But they are also layered memories, inner skins we cannot shed even long after they fail to keep us warm.

R and I met in 1975, more than 30 years before you were born. A Londoner hitchhiking in France, he came to Aix-en-Provence where I was a student. He was nineteen. I was twenty. In a small group of mutual friends, we walked around town, taking detours down narrow side streets. R and I fixed on one another immediately. Under cover of the group, we glanced across cafe tables, made lines of sight, chose this chair rather than that chair, turned and tilted this way rather than that, listened in on one another's conversations and began to interject. My life with him began like this, and with a shared love of written and spoken words. We talked about novels and song lyrics. We told our life stories over coffees and beers. We criticized our parents. We described our places—my Great Lakes, his England. While playing pinball in the corner café, he told me what he knew about Wittgenstein, which it turned out wasn't all that much. And—yes I'm afraid this is what it meant to study in France in the 1970s—I told him what I knew about semiotics, which also wasn't much. I told him about reading Chateaubriand by way of Todorov.

When our group stumbled out of the cafés for midnight rambles around Aix, R and I pulled away from the others. We compressed our pasts; revealed our naïve ambitions. It was as though we had missed an earlier meeting and now we were in a hurry. I had never before fallen in love by incessant talking. I loved his voice, his olive skin and grey-blue eyes, his fisherman's sweater, the black onyx ring on his right hand. His bad French, the electricity of London in his slang and clothes. He was a city I did not yet know, and I am crazy for cities.

He went back to his father's house in Cricklewood, north London. I wrote to him. He opened my letter, he later told me, in a freezing fog on the platform of Kilburn station. I think now, perhaps I should not have written. It would have ended there. But I wrote and he replied. More words. Agitated writing followed by agitated waiting. Many rounds. Watching for the postman. Listening for the swish of mail pushed through the box and dropping to the floor. That letter-writing world, for love affairs, for the beginnings and endings of love, has gone. By the time we reached our end, he and I were firing deadly texts and emails like bullets.

By the following January, I had written to confide my feelings. A week later, the Mistral was blowing in Provence, the propane bottle in our student house was empty and none of us had money to replace it. We turned on the hotplates of our electric cooker and heated cheap wine in a saucepan. We sat at the kitchen table, wearing winter coats and talking about essays that were soon due and how it was too cold to hold a pen. The bell rang. It was a telegram from R: Arriving. Stop. Phone if inconvenient. Stop. Love can be an emergency.

We went to a tiny inn at Les Baux, the most beautiful place in striking distance that I knew. Almost no one there in winter months. We walked, ate bread and cheese, had baths and made love. On our last day there, we hiked to a limestone outcrop with wide views across the Alpilles. Below us, there were ancient vines and olive groves, wild thyme and lavender waiting for spring. Icy gusts and no one else in sight. We sat down near the edge, shivering while R rolled a joint. I watched him curl over it to keep it out of the wind. We smoked it. I wasn't used to getting high and it left me lightheaded. What if we had fallen? What if one had fallen and the other walked away? In those first days together, each of us knew the fleeting but unsettling desire to be free of a person who has got too close too fast. We talked about it later, curled in one another's arms.

I wish I could look back on those first days and find comfort. But right now, I see only my mistakes. The sacrifice of our respective youths to one another. I see how hard it is to know another person and be known. How unversed we were. How little we knew about love, personhood and autonomy. What I want more than anything is for the two of us to look at one another one last time with tenderness and remembrance. I want us to sit with Isaac. Be with him. Say sorry. I want us to say that despite the imprisonment of marriage and our painful release, we are glad we happened to one another. But I don't think we are going to manage it.

London

Agnes, I tried not to compare you to Maisie, but for the first year or two, I failed. She was the slender beauty with a shiny black coat and Collie flash down the front, her left hind foot dipped in white. You were the burly interloper, your coat dry and coarse. You were less affectionate, less pliant, less comprehensible. Maisie craved physical contact. You were guarded. Maisie loved to be stroked all over, whereas you were particular. It took time to discover your fondness for having your legs stroked, an unusual preference. Nowadays, you allow me to massage your sore joints and muscles, and I can see it feels good to you. But I learned early that sometimes you did not wish to be touched at all and if I tried, you would rear away or raise a paw to deflect me.

Maisie gave ground. She sought to do what we wished and make herself one of us. With Maisie, I continued to believe in the notion of dogs and unconditional love, and I wish I could say sorry to her now. You, Agnes, have been teaching me to think otherwise. And it seems I am not alone among dog people. In her Companion Species Manifesto, Donna Haraway has this to say about unconditional love and dogs:

...people, burdened with misrecognition, contradiction, and complexity in their relations with other humans, find solace in unconditional love from their dogs. In turn, people love their dogs as children. In my opinion, both of these beliefs are not only based on mistakes, if not lies, but also they are in themselves abusive-to dogs and to humans. A cursory glance shows that dogs and humans have always had a vast range of ways of relating... Because I find the love of and between historically situated dogs and humans precious, dissenting from the discourse of unconditional love matters.

You asserted your dogness in our family, even if it meant that we might love you less. For some years, I believed I would love you less than Maisie. Yes, it's a sad fact that we humans crave contests. We like winners and best friends. Take Dorothy, that most human of humans, courageous girl in gingham dress and ruby slippers. She had to whisper to Scarecrow (because Lion and Tin Man were in earshot), "I think I'll miss you most of all." I remember how this shocked me as a child and how powerful it was, causing me to prefer the Scarecrow to this day. Each year, for the 364 days that I do not watch the film, I miss the Scarecrow "most of all." And the day I watch it, I choke up when Dorothy reaches that line and resets the scarecrow-missing for another year.

Of course the source of Dorothy's troubles was, need I remind you, her dog. Toto was, like you Agnes, something of a rogue. Do you remember our first fight? It was a wet Yorkshire winter that followed your arrival and you returned from most walks covered in mud. We had to bathe you several times a week. You prized the event, standing solemnly as we washed you. But one evening, you peeped into the bathroom to find me enjoying a hot soak in what you clearly thought was your tub. You growled, barked, tried to grab my arm, and finally leapt in, covering me in scratches and splashing soapy water over the sides of the tub. For my next few baths, R accompanied you into the room and made you sit on the bath mat. You never tried to evict me from the tub again, but continued to wait beside it when I bathed, and ran to it after walks, muddy or not, hopeful of warm water and dog shampoo.

Claims to the sofa were less violent, but persistent. If one of us vacated our spot, you moved to occupy it, only to resist our efforts to remove you by collapsing into a heap of dead weight. Once pushed from the sofa, you might sneak to our bedroom and spend an hour shedding your golden hairs on the quilt for us to find at bedtime. There was a Chaplinesque physicality to these manoeuvres that won our admiration. A local dog trainer described such behaviours as power grabs, attempts to climb the hierarchy or become top dog. But I was tiring of his interpretations and his tips made no difference anyway. I believed more and more that for you, to occupy our spaces was to assert both intimacy and agency, not to take away ours. You sought to draw close to our bodies and smells. Close, yet self-standing. This was you.

Walking too, was more of a chore with you than with Maisie. She carried her rubber ring on every walk, demanding only that we throw it for her along the way, and the game served as a distraction from mischief with other dogs or walkers. You chased the ring twice, then lost interest. Tennis balls? Same result. Soft or squeaky toys that you could shake and chew attracted greater interest, but you preferred to leave these on the step at home, only to collect them on your return. For you, walking has always meant bodily freedom. An opportunity to roll in fox shit, scavenge, and chase other animals. In Yorkshire, this was serious when sheep were on the moors. When we moved to Cambridge, you shifted your attention to the cows, wild rabbits, and student picnics in Grantchester Meadows. Sadly, this resulted in your spending more time on the leash, a reduction of the freedom you craved.

You were four years old when R took a teaching post in London. We found a flat in Golders Green, which proved perfect. It had a large back garden and was within walking distance of Hampstead Heath. No sheep, rarely sign of a rabbit. Here, there were squirrels and they raced up the trees when they saw you. R and I smiled at the sight of you happily growling and circling beneath the teetering branches. "Looks like our dog is a city girl," he said. And it was true. We were able to let you off the leash far more in London than in the country. You liked to charge back and forth on the Heath's open spaces. Along its wooded paths, we still lost you now and again, but it was more likely the draw of one of those banana peels discarded by a walker than something with four legs and a life to preserve. And finally, you found the company of other dogs. As never before. The Heath, I do believe, is owned by the dogs of north London and you became one of them.

I doubt you remember how R and I shared the task of walking you. Increasingly, we took turns, sometimes arguing about whose day it was. Yet there were times when you cemented us in the way Maisie once did. "Walk with me," I would say to R. "We can talk about your work." As he rightly pointed out, this was bribery. But it went two ways. We were both writing, and depended heavily on one another's reading and encouragement. Walking you provided time away from phones and computers to move our limbs and trade ideas. Even in the end days of arguments (silent or not), these ambling workshops still occurred, though less frequently and less successfully.

Know

Agnes, there are things humans know before we know them, and things we try to tell without telling them. Perhaps this is why on April 12 in 2011, R went out to the garden to make a phone call, leaving his inbox open on his laptop. And perhaps this is why I immediately sat down at his desk and began to open a series of emails from L, a younger colleague in his university department. I read them. Even as the blade went through me, I was not shocked. And although I believed the affair would not last, I knew we were finally done. He moved out the following day. Two days later, Isaac arrived for his 23rd birthday dinner to find only me. I explained that the three of us were a family no more.

But Agnes, what did I know without knowing? That R could not leave me but could not be truthful either? That he would break my heart? That he needed to go, for his sake and mine? That his unhappiness was constitutional and could not be mended? Or was it something constitutional about me? Did I know that there are people who are bound to end up alone and that I might be one of them? That humans are blocked by angst? That some of us cannot love a person or place, including our own family and home, without an underlying tug of disquietude?

It was R who once pointed out that in many of my childhood photographs, I appear to be looking away from people and places, as though I wished myself elsewhere. I was the person, after all, who would one day write a thesis critically undermining my own deep attachment to Garden City, the unprepossessing fifties suburb outside Detroit where that childhood was spent.

I still dream, perpetually conflicted, of that suburb and its box houses. I dream of Detroit, where I should have lived, but never did. I dream of people an ocean away, some of them now in the ground. But I chose to leave. I put an ocean between Detroit and me, my parents and me. And something tells me I may yet put an ocean between R and me. If I can't go gently, then maybe I should go far.

What did I know before I knew, before these events of 2011 made knowing so much more urgent? When all else was stripped away, if only I had stopped to look, there was you. Your silence, hunger, stubbornness, readiness to scavenge; your thick coat and dark eyes. Your sharp teeth. Your daily needs and fears. Your wish that I would play more often, hide behind trees along the path like I used to do, so that you might find me. Your history. Dog history. Your long wait for me to acknowledge you. You were there when I told Isaac. If only I had looked. Yes, your long wait for me. Haraway remarks that "if I have a dog, my dog has a human." Even that, I could not see.

Trouble

R was gone, that was one thing. The knowledge that he had the company of a new person was another. Hard as I tried, I could not escape the feeling that I was a person discarded. Without value. This, to me, was the message of an ending by affair or more precisely, by deception. The deceived one is not only emptied of value, but in the dark. It was destabilizing to try to piece together what had happened without the participation of the other person. I saw that after more than 30 years, I was supposed to stop loving and move on, without talk and without comfort. It was a desolation I had never experienced and it impacted all my efforts to reconstitute myself.

Anger and sadness became routine and I was not very attentive to you, Agnes, I know. Not only did I talk to myself, but after several months, I began writing furiously. I wrote bitter emails to R that made matters worse. I wrote stories. These were junk and I threw most of them away. I sat at my computer drinking coffee, muttering, and ignoring you. When we walked, I always took the same route, checking my phone as we went, mind elsewhere, letting you plunge into the woods and eat whatever garbage you found. But you're a funny one, Agnes. You noticed my torment, and this brought a gradual shift in our relationship to one another and the world outside us. We grew a shield that, I believe, came as much from you as it did from me. Only Isaac, who lived nearby in a student flat, was allowed to cross it.

There were friends. My friends were your friends. You liked them all, and you were inordinately excited whenever one of them joined us for a walk. Especially Rhonda, who came often and invited us back to sit in her kitchen for tea or a glass of wine. But even now you find it hard to settle in a friend's house, typically waiting by the front door, afraid I will leave without you. You pick up your leash repeatedly and carry it to me as a message. As if to say yes you can stop here, but when you go, you're taking me with you, right? At the vet, you enter a state of terror. Wailing, mouthing his hands, licking furiously. Again, you grasp your leash and wave it lethally in his tiny examination room. For god's sake, Amy, he's nice and all, but get me out of here. At home, if the bell rings, your bark is deep and loud. Only yesterday, I opened the door to find your order of dog food on the porch and the delivery man running away in fright. "She's really friendly!" I called after him.

Of course, you still leave me behind on walks and did so even during my darkest days, reminding me that to you, eats and bodily freedom rival all other allegiances. There was the time by Jack Straw's Castle (sadly no longer a pub), when you darted across the four lanes of traffic of North End Way and Spaniards Road for a discarded Kentucky Fried Chicken carton. As I chased you down, disgruntled people climbed out of their cars. "Get your dog under control!" a man shouted. "She's not mine!" I shouted back. Yes, I said that about you. It was a bad day, not long after the break up, and R and I had been fighting by text. I couldn't bear the anger of another man, so I told a lie.

When I caught up with you, pulled you off the road and tried to prise a chicken bone from your mouth, you accidentally bit me and I bled. Back home, I sat on the sofa, holding up my finger wrapped in paper towel, blood oozing through. I thought about the many times R had given me first aid after some mishap. His hands, his voice. He was good at it, always knew what to do. He found such tenderness when another person was ill or injured. When I first knew him and we were in France, I caught a cold that went to my chest. R's French was dreadful, but he went to la pharmacie, affected his best accent, asked for l'expectorant and returned with the right medicine. I remembered that day again, pictured him sitting on the edge of my bed in a poorly heated room, holding bottle and spoon, making me laugh till I coughed as he read out the dosage instructions in his exaggerated, bad French. But now he was gone and you sat across from me, watchful and wary, while I held my finger and muttered mean things about you and about him. I cursed you for biting me. I cursed R even as I longed for him. Cursed him for not being there and for leaving you in my care. It was the first sign of trouble between you and me. It would grow worse with each passing month and year.

The bitterness of summer

"Agnes has to be put down."

Three summers ago, you and I were walking with a friend when that line about you, histrionic and unbidden, first escaped my mouth. We were on the river path near home and you ambled a few paces ahead, within earshot of my voice.

"What? Is she sick?" My friend was aghast.

"No, she's not sick. But I can't do this anymore. I am trapped by her. How do I do that thing I am fucking supposed to do: move on." (It wasn't a question.) "I can't even stay out all night. Can't move abroad or make any life-changing decisions. Agnes dominates each day. Ever since the divorce, there is only me. I am her world. It's been five years now and I can never get those years back. No one else will have her and there is nothing I can do about it. So you tell me! What is the solution!" More questions that were not questions, but a salvo of reasons spat like rocket bursts.

I stopped to take a breath so quick that the pause was gone before my friend might venture the tiniest objection. Nor did I seek her comfort or agreement. I wanted my missiles to land on the earth surrounding us and carve out a crater. In that crater, I saw my beautiful golden dog in death. I sat beside her, barren, free of her, howling in her place. No, there should be no solution offered by my friend. Only her silent recognition of my predicament, her acquiescence in a dark vision. I was not ready to be debated or cajoled.

These were the toxic ingredients packed into that sliver of a pause and then I declaimed further, vehemently, to forestall all mitigation and finally, to stop myself from what I feared would be a torrent of delayed grief. Grief for lost marriage, the breakdown of our family, financial fallout, my father's recent and sudden death, the passing of my youth, the turning of my luck. Yes, I knew very well that I had lived a lucky life. This now served to compound my disbelief that it had gone so badly wrong. That the only luck remaining was the dumb luck of a faithful dog, perhaps only faithful because she too had lost a person and was now stuck with crazed me and had to make the best of it. A dog so faithful that she would not die and leave me alone, even though her death might finally free me from the last sad vestiges of my past.

"There is nothing I can plan or do without first considering Agnes. I can't leave her for more than a few hours without worrying about her hunger, thirst, her pissing and pooping, her loneliness. It impacts on what work I take. It impacts on friendships and relationships. There are no holidays longer than a few days. Pet sitters are expensive and she's too high maintenance for most friends. Each summer, I read the holiday posts on Facebook. I try to be a good person. There is a better, more generous self. I try to keep that person alive. So I post comments. Enjoy your holidays! Looks wonderful! Travel safe! But within weeks of summer's start, with Facebook holiday news accumulating, I see pictures of mountains, beaches, alfresco meals, gatherings of other families. Soon, I begin to cry. I cry when I log onto Facebook. It's pathetic. I become stir crazy, resentful of the freedom of movement of others. Resentful of oceans, national parks, romantic dinners overlooking lakes, family reunions. Then I hate myself for resenting such beautiful things, for my jealousy of friends who deserve their holidays, marriages, families, travels. So, I go off Facebook to cauterize this outbreak of resentment. I wait until they all come back and start complaining about winter and their jobs. Every year, I despair at my lack of emotional progress. Then before too long, I start blaming the dog for it. I yell out to a room, empty but for her sweet presence. 'Fuck! I am losing years of my life to a dog.'"

A note of hysteria whistled through these words, and finally, my throat grew a huge lump and I choked on them. I stopped if only to push down that lump because I believed that if I started to cry, I might not stop. Of course this crying was about so much more than you, Agnes. But you had become its cipher, its bearer. You embodied a share of the grief because I could not carry it all in my own body. You were both the last reminder of my marriage and the last unsolved problem of divorce.

My friend was silent for a minute or two, sensing that I might lash out should she say something sensible, and giving me time to push back the sobs that rose to my throat and pressed behind my eyes. But then, tentatively, she tried. "Would you ever consider re-homing her?"

"What are you talking about?" I said angrily. "Have you understood nothing? I could never do that to Agnes. She would be so frightened, so bewildered. She'd spend the rest of her life waiting for me to return. That's why the only solution is to kill her. That's the whole point!"

Agnes, you don't remember that day. You could not have grasped the human meaning of my words, but I know that you heard them and the shifts in vocal register that accompanied them, and you translated these to a dog's mute apprehension. You glanced up at me in faint alarm, wondered if you had done wrong, waited for it to pass, and trusted me not to kill you.

Summers come and summers go. Although I still grow restive sometime in late July or August, we now make it through without anger or incident. And the other seasons too. We walk every day. Long walks, short walks. The two of us, or with friends and other dogs. Rain, sunshine, wind, snow. At home, I turn to look at you. You open one eye. I push my chair back from my desk. You lift your head and watch me. I leave the room to pour another coffee or rattle around in the kitchen. You lumber in behind me. I go out often and leave you behind. You don't like it, but you don't object. I have friends, work, meetings, parties, outings that don't include you. I like coming home, knowing you are there. I like it too much to lose it now. At the end of the day, you join me on the sofa and I massage your sore joints until it's time to sleep. It seems that you Agnes, in your dogness, make me a better person.

Coda: one two one

Amy one: But some days, I miss R with an anguish that shocks me.

Amy two: Too bad. Some people should be alone. You are probably one of them.

Agnes (who is one): Amy, you are not alone.

Amy two: I am alone.

Agnes: I'm here.

Amy one: I don't know what's wrong with me today. I feel unloved and afraid.

Agnes: Well, shall we go for a walk?

Amy one and two: What's the point of that?

Agnes: I will be by your side. Then I'll wander off the path into the woods. Love will be the same wherever I am. Whether you see me or not. You humans never seem to understand that alone and together are the same. You are always trying to break them apart and you make yourselves unhappy. But I can teach you, Amy. You are more like me than you know. Just walk with me.

We walk out together. I am thinking about a passage in a book I read, Melancholia's Dog by Alice Kuzniar. She writes of a child who often says she needs to be alone and then takes her golden retriever for a walk. I am thinking about the mystery of you. "What she was, I can never know: how can one penetrate the soul of a dog?" wrote Colette Audry after the death of her dog, Douchka. I feel your thick coat as it brushes my hand. You move ahead a few paces, then glance back to check on me.

A girl, five or six years old, pulls up on her scooter. She chats to me and asks our names. Most children find you more interesting than me. They only ask your name, never mine. They ask your name, and the braver ones want to stroke you. But this strange little girl asks my name, then yours. We talk about nothing much until we reach the corner, then she says, "I don't think I will see you again because I live in London." I tell her I live in London too, so we might see one another. "In fact, I come down this street nearly every day because it leads to the park where we walk. So, maybe I'll see you." The girl seems pleased. As we cross the street, she calls after us, "Goodbye, Amy. I hope you and Agnes will be all right."