Image courtesy of British Library Photostream

She drove home eager to tell her husband about her new client, an international man of mystery. Maybe. He'd suggested he'd worked as a spy in "the Levant," and his untrimmed, high-climbing beard was consistent with being undercover in the Middle East. It was also, however, consistent with being mentally ill.

Not her typical client, in any case.

Lauren found Daniel in the kitchen pouring scotch over ice and could tell his curtain of self-absorption was drawn. She'd have to wait to tell him about her client.

"What's wrong?" she said.

"I'm thinking of all the reviews I'll get."

In a televised interview, Obama had called Daniel's new book "brilliant." It was the greatest thing that had ever happened to him. It was making him miserable.

Lauren herself wasn't thrilled; his career would now take up even more space in their life. Their middle daughter Allie had just started Wesleyan; Sheera was an independent fifteen. This was when Lauren was supposed to do things she'd put off for two decades, like get serious about gardening and take on a full load of clients. Instead, she found herself planning a posh book party and navigating Daniel's neuroses.

"This is a bad thing?" Lauren said.

"You know how reviewers are: they'll aim to take the book down precisely because Obama praised it. I'm fucked, absolutely fucked."

She found his pessimism endearing—what a Jew—but also frustrating. Couldn't he just, for once, be happy? "You should give reviewers more credit. Or less. I mean, if Obama has an effect, they'll parrot him, right? Isn't that the way it works?"

Daniel looked past her, staring out from deep inside his head. The lines on his face sectioned it off. Every year he looked less nerdish and more distinguished. Last week, her friend had actually called him handsome. For all his scotch and anxiety, he was aging well. His hair was still full. Most of her friends, by contrast, found themselves living with old men. She noted this now, making a case to herself.

Lauren said, "We should go into the city tomorrow, check out the party space."

"Oy."

"I know this is very un-you. But it can only help."

She didn't know why she was pushing him to have a fancy party. Yes, she did. Two college tuitions were chewing through their savings, and they'd soon face a third. More than a million dollars combined. Financial anxiety had become a fixture in her middle-of-the-night montage, alongside fear for her children, existential panic, and general life regrets. There was a chance now, thanks to Obama, she'd be free of it.

"It's marketing," she said. "It's necessary."

"It's so un-me."

She wanted to tell him to suck it up and stop whining. The guy never did anything he didn't want to do. And he'll probably end up enjoying the party; he'll be the center of attention, after all. "It's just one night," she said.

"Let's at least have real food. Meatballs and egg rolls. Chicken wings. Not, you know, drizzled balsamic this and that."

In light of his appeal for "real" food, her planned dinner, frisee salad with poached eggs, seemed effete. But it was his favorite meal these days. She took the eggs out of the water too soon and two of the four fell apart. She was furious at herself. Slow down! She gave him the two intact eggs because she didn't want to hear him complain.

It was warm enough to eat on the patio. They sat next to each other, facing the river. Alcohol had curbed Daniel's anxiety and made him capable of hearing her, so she brought up her client. "I had trouble getting a handle on him. He's gruff but erudite, in a way. Kind of formal? He seemed authoritative, but some of the things he said seemed like bullshit."

"Like what?"

"He was talking about Syria, the mess there, and he hinted he was involved in the uprising against Assad."

"He's a loon. Or a liar. The revolution in Syria is a western plot—that's a popular conspiracy theory among anti-American nuts."

Lauren deflated. Only now did she realize how much the prospect of treating Christos Kosco—Jesus, even his name was fake!—had excited her.

On the other hand, a man who pretended or believed he'd been a spy: that was interesting in its own right.

A police officer in Damascus once stopped me on the street and demanded to know my business. I lied in fluent Arabic. Today I was too nervous to leave a message on the pharmacist's voicemail. A man who once slept on cement to the sound of shelling now requires a narcotic to sleep for even two hours. When I wake in the night, I "make the rounds" in my new house. To the kitchen for water. The recliner for reading. The computer for research. Et cetera. I pretend to hide from sleep and wait for it to find me. Usually it doesn't, however. Most days I give up / get up at 4:00 to 4:15.

During the initial days of my retirement, I was calm, if disoriented. Then one morning as I walked on Main Street toward the coffee shop, my surroundings started to appear menacing. A German Shepard grinned at me. If my psycho-emotional state does not presently improve, my reentry program will require modification.

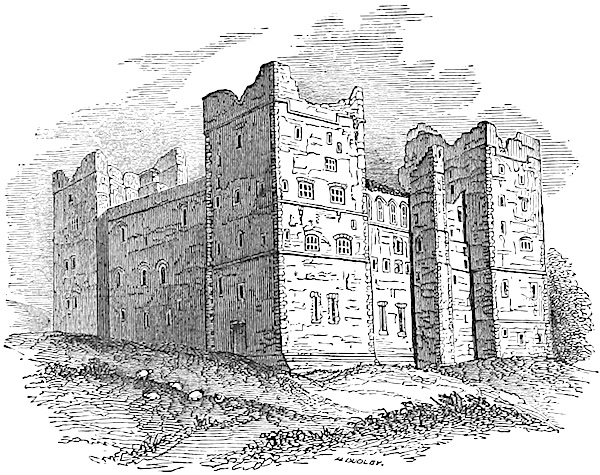

I live in what is often described as a "leafy suburb." I felt I deserved a bounty and wanted it in the form of a life deep inside the castle. Here I am, ensconced behind moat and drawbridge. The property of one of my former bosses, William Jefferson Clinton, begins 8.8 miles from the end of my driveway. I like to imagine Clinton, somehow made aware of my service, invites me to his estate to thank me. Such a desire for appreciation is considered shameful in my profession. I attribute it to my living here amongst all these rich and oblivious people. They believe comfort / peace of mind is their birthright and would be horrified to learn that it is, in fact, the spoils of empire, violence, et cetera.

My house is 6.3 miles from the house in which I lived before my mother abandoned us. My father then moved my brother and me into an apartment by the Cross Bronx Expressway, a busy section of the busiest highway in the USA (I-95). Dr. Brown-Jonas suggested by moving to Westchester County I was trying to recreate the lost home of my youth. A plausible theory given I chose not to live in the DC "burbs," the favored home of spies current and former. Contrariwise, I'm a New Yorker if I'm anything and didn't want to reside in the "big city," so this is a logical home for me even without psychoanalytic interpretations.

I'm reserving judgment on Dr. Brown-Jonas. She seems a) intelligent b) kind c) skilled, having smoothly ushered me through my first-ever therapy session. However, I have no cause to believe she deviates from her demographic norm in terms of obliviousness, sense of entitlement, Lexus liberalism, et cetera.

Indeed, she is the wife of Daniel Weiss, a former Time columnist who writes about American "foreign policy" with an emphasis on the Middle East. Yet he can't speak even rudimentary Arabic and presumes to understand the region because he touches down in Tel Aviv or Cairo for choreographed visits with dignitaries and "activists." A liberal "internationalist," he supports American wars but tsk-tsks American torture and argues "we" should foster human rights. As if "we" could. As if "we" would ever choose to.

Make no mistake: such propaganda is necessary. What chafes is the notion functionaries such as Weiss are performing an elevated/edifying task. As far as I know, Weiss isn't amongst the journalists on the Agency payroll; if he were, he might be cognizant of his function. With his ostensible independence, he is able to believe he is striving to make US "foreign policy" more humane. In reality, he provides cover for American power—and benefits from it. His house, listed at $1.7 million when he bought it nine years ago, was described by his realtor as a "Luxurious and Modern Hudson River Hideaway."

This morning, however, (4:12 am), I've accessed a video that gives me hope for Dr. Brown-Jonas. It shows Weiss reading at Politics and Prose bookstore in DC. He has wavy silver hair he periodically brushes off his brow with his fingertips. He would present as "dashing" if not for his nasal ("nebbishy") voice. As he reads about FDR's "bold leadership on human rights," the camera cuts to the audience and there is Dr. Brown-Jonas, mouth open, as if pulled ajar by her large lower lip, looking incredulous, like: What the fuck is this shit?

Hypothesis: the doctor is a dissident.

Her office is 4.9 miles from here, in a yellow-shingled Victorian where downtown turns residential. It reminds me of a house I visited five times when I was attending Harvard, my roommate Charlie's family's home, which was a ten to twelve-minute walk from our dormitory. Charlie and I once slurped down spaghetti carbonara at the "farmer's table" in the "country kitchen." On another occasion, people around the table viciously snickered when I experienced a "brain hiccup" and called the soup chanterelle instead of bouillabaisse.

The nervousness subsided considerably in Dr. Brown-Jonas's office. You wait in a living room area with a window "looking out on" the porch. She opens the door and greets you with a smile. Her office looks like her: bohemian, classy but "arty." She has dangling earrings and dangling plants. The scarf on her neck resembles the tapestry on the wall. You sit in a corduroy chair and she sits in its twin with a notepad on her lap. She has oval glasses and hair even curlier than yours. She smiles and waits for you to speak.

CHRISTOS: I feel like I should have been more open last time.

LAUREN: You can be more open now.

C: I worked for the CIA. I see no reason why I can't tell you that.

L: You were a spy.

C: Correct. I was an operations officer in the Clandestine Services. That's what I did with my life.

L: And… did you find it a fulfilling career?

C: I did. But it was taxing. Suffice to say, world domination doesn't come easy.

L:

C: What?

L: I think it would helpful for you to tell me about your experiences.

C: Let me ask—what are your confidentiality requirements?

L: In general, I'm required to keep confidentiality except when I might prevent harm to you or someone else.

C: I see.

L:

C: I tortured people. I killed people.

L: [writes in her notepad] Do you want to tell me more?

C: No.

L: The things you're saying you did—

C: I did them.

L: They can be traumatic.

C: You should have seen the people I tortured.

L: Christos—

C: Let me tell you, torture was traumatic for the people I tortured.

L: No doubt. But you're here, they're not.

C:

L: Do you see a link between what you did and the difficulties that led you to contact me?

C: Yes, but not in the way you're thinking.

L: The way I'm thinking—which way is that?

C: That I'm wracked with guilt, it's eating me up, et cetera.

L: What is the link, then?

C: You have an extreme existence, and then you try to live a regular existence.

L: You're having trouble adjusting to a more conventional life.

C: Correct. There is disorientation, nervousness.

L: So you feel basically okay about the things—"

C: Yes.

L:

C: What I did, it's necessary. Trust me, most Americans want me to do what I did, or they would want, because they have fucking no clue.

L: You seem angry.

C: I am. I make no bones. Americans are clueless, absolutely clueless.

L: You performed a service for the country.

C: Correct.

L: And you feel underappreciated?

C: Some recognition would be valued, yes, but let's not make this about me.

L: Who is it about?

C: Who is it about? It is about Americans demanding wealth but not wanting to know what it takes. It's about me doing the work while you cultivate hydroponic kale.

L: [pauses] You've done your due diligence.

C: Google. Everyone is a spy nowadays.

L: True. True.

C: What would your husband think of what I've said here today?

L: [pauses] I don't know. I suspect he would say America need not do all that dirty work in order to prosper, that indeed it's counterproductive.

C: Yet he supported US wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya…

L: He didn't support the Libya war.

C: Incorrect, doctor.

L: Anyway, those wars weren't about my kale.

C: Incorrect.

L: We've gotten way off track. How are you doing? How was your sleep this week?

C: Bad. Worse. My mind refuses to shut down. And when I force it to with the Ambien, I wake up shortly after. Nervousness in my chest jerks me awake.

L: We should consider medication. But we can first discuss cognitive coping techniques.

C:

L: Why are you smiling?

C: It sounds like something from my training: cognitive coping techniques. I assumed you would want me to talk my about, you know, my childhood, my mother, et cetera.

L: I think that's a good idea, actually. Why don't you tell me about your mother.

C: You probably assume I've repressed it, but I actually think about it quite often.

L: What? Think about what?

C: At the time my father told us she had to check herself into a mental institution, but many years later my brother told me she ran away with another man. I believe my brother's version of events because I remember the last time I saw her. It was early in the morning, still dark. I'd gotten up to watch cartoons. My mother startled when she saw me. She kissed me and said I could watch as many cartoons as I wanted. She didn't seem mentally impaired in any way. She seemed to be sneaking away. Later that day, my father told us she was gone and would never come home. You know what he told us to do?

L: What?

C: He told us to, quote, pretend it's normal. He said that all the time. It became a joke between my brother and me. When one of us got hit in the scrotal area, the other would say, "Pretend it's normal." When one of us was vomiting, "Pretend it's normal." We moved into an apartment by the Cross Bronx Expressway. He must have been having money troubles. Perhaps that's why my mother left. The noise never stopped. Twenty-four hours a day. It was like trying to sleep in the breakdown lane. "Pretend it's normal," my father said.

Just before they were supposed to leave to check out the party space, she found Daniel at his desk in sweats and slippers. "I'm really sorry," he said, "You'll have to go without me. I just can't let the book rollout get in the way of work."

Better to be alone with herself than with him, so she said, "Fine." She stepped out of the room then stepped back in. "You know what? It's not fine. You're coming."

He consented with a sigh. Now she had to wait for him. She went down and cleaned the kitchen while he—she knew his drill—struggled to find sufficiently comfy clothes. Socks would be a particular challenge. Once downstairs, he came into the kitchen and took a roll of Rolaids from the drawer and a granola bar from the cabinet. Then deliberation at the closet. After checking the weather on his phone, he opted for his trench coat. Then into the bathroom to pee and primp. His vanity centered on hair, which he mussed just so.

Daniel's easy life was hard for him. His life was hard for him because it was easy. Over the years, he'd taken—she'd given him—all that time for himself, which he'd used not only to work but also to indulge his wants, which as a result had hardened into needs. Taking care of three girls, she'd not had the luxury of being able to obsess over socks.

Yet things undoable for her, like appearing on Meet the Press or giving a speech, Daniel handled with ease. He was serene in the spotlight, holding forth.

On the Saw Mill, Daniel reclined in the passenger seat and closed his eyes either to work in his head or manage motion sickness. "You okay?" she said. "Daniel?"

"Shh. Please. I'm working out a connection."

Daniel stayed "in thought" all the way into the city. The restaurant was two blocks from their first place, a studio on Horatio Street. He was something back then, intense, crusading. He wrote a Voice cover story on police brutality. He was never radical, but he was—what? A truth-teller? A journalist, certainly.

What was he now?

Christos, she couldn't deny, had gotten in her head. She'd begun to believe he really had been a spy. She had no proof, though, and what'd she know from the CIA? A Christos Kosco had graduated from Harvard in 1977, at least that much was true.

But if he'd actually brutalized people, wouldn't he trigger visceral distaste in her? Wouldn't he horrify her a little? He did. He horrified her a little.

Trips into the city were so rare for Lauren these days, even the mellow West Village made her dizzy. She was relieved when she found a parking spot. "Can I have your phone?" Daniel said, and she waited on the sidewalk while he sat there, still reclined, and transferred what was in his head to his voicemail.

"See where we are?" she said once they were on their way.

He stopped and looked around. "Aha. Back where it all began, our own Horatio Alger story." This was funny in spite of being not funny, not because it was a bad pun but because it was bad pun he'd made 30 years ago and not since. A thread of shared experience that, tangled up with a billion others, had weight. She couldn't conceive of leaving him. The number of divorces amazed her. Were all those people more miserable than she was, or just braver?

The restaurant, a tapas place, was on a list the publicist had provided. The woman who greeted them was ridiculously beautiful. She looked black-Asian and wore short black shorts and a white shirt with bulbous sleeves. Above her red headband, her hair rose to astounding heights. She had a British accent. As she went up the stairs in front of them, her calf muscles showed themselves. Daniel, who used to have a relentless erection, didn't notice. She led them to the space, then went to "fetch a few nibs."

"Oy," Daniel said.

With the velvety couches, half-light, and Persian rugs, the place was too cool for a Daniel Weiss book party. But they could pull this off. Hell, they'd gone to CBGBs back in the day. They'd seen Blondie! Daniel looked ready to vomit. "This will work," Lauren said.

The goddess returned, and Lauren was relieved the food wasn't foofy. Calamari. Meatballs. Shrimp. All quite good. "You wanted meatballs," Lauren said.

"Fine," Daniel said. "Can you make the arrangements? I need air."

"He's cute," the woman said after he'd left.

Although she probably meant cute like a scared puppy, Lauren was glad for the compliment. "President Obama praised his book," she said, astonishing herself.

Air puffed from her mouth. "Politics—not my cup."

"Nor mine."

"Credit card, please?"

Outside Daniel was pacing in the little park across the street, wearing a trench coat in the sun. He looked like a crazy person.

She put her hand on his shoulder to stop him. "That space is fine," she said.

"The Times Arts section called, they're doing a profile."

She wouldn't have liked him if he were as cocksure as he came across in his public appearances. Often, with his kvetching and neediness and lazy demands, she felt exploited by him. Yet caring for him also fulfilled a need in her. His pain now, this was real. She could feel it. He leaned into her, and she held him.

"My dreams are coming true," he said, "and I'm miserable."

"This is a heady time."

"Thanks for putting up with me. I know I've been difficult."

"Hey, as long as we're in the city, let's go have a nice lunch."

"Actually, sweetie. I need to get back."

I'm driving in my Lexus toward Main Street where I will park and proceed on foot to the independent coffee shop to purchase and consume a "Chai Latte" and a wedge of banana walnut bread. Dr. Brown-Jonas has urged me to put in place a routine and other elements of "normalcy" such as social interaction. This is easier said than done, however. I know only two people in the area, a morose man with halitosis named Manfred whom I met in Riyadh and my cousin Bridgette (my father's cousin's daughter) who pronounces her name "Brigitte" to make herself seem exotic. I fail to see what talking to / seeing them would accomplish in term of stress-alleviation. And the mere thought of engaging with strangers—joining a club, for example, or a "book group"—intensifies the nervousness. So, currently the "social" component of my daily routine consists of this mid-morning mission. It is again proving to be a formidable challenge. As I get out of my car, I feel I'm entering a hostile environment where everyone is 1) acutely aware of my presence 2) monitoring my movements and 3) amused/angered by my appearance. My rational mind understands this is inaccurate either in part or in toto and that the three people within eyeshot have little to no interest in me. Still, I cannot shake the sensation the elderly woman standing with her poodle by the florist is staring at me, and I check for breakfast detritus in my beard. All clean as far as I can tell. To confirm, I bend down to look in the rearview mirror of a parked SUV, but my close proximity to the vehicle arouses the suspicions of a man wearing large earphones, who stands up from a bench, his eyes fixed on me, and I expect him to pull out a firearm from his shoulder bag even though I'm almost certain he won't. I straighten up and proceed. My shirt is sticking to my back. It's only 76 degrees, nothing for a man who endured summers in Baghdad, but nervousness activates the sweat glands and sleep deprivation throws off the body's temperature regulation system. My brain feels as if it's sealed in plastic wrap, a result of the Ambien I've come to rely on to produce 1.5 to 3 hours of sleep and which I've come to regard as insidious, an enslaving poison threatening to deprive me of all mental acuity.

As I step inside the shop, déjà vu strikes in flashes, a supersonic slideshow in my brain, the memory just beyond reach, as if I've been coming here night after night in my sleep. The seven people in the place look at me. The barista, a bald "hipster" who has mutilated his earlobes, smiles and nearly laughs at me.

Operationalizing Dr. Brown-Jonas's suggestion I "send" myself positive messages, I think this: the barista's opinion of me is of zero importance.

And this: I could kill him with a single blow to the throat.

Three days before the book party, Daniel's self-involvement was so all-consuming, Lauren considered putting off pizza and beer night. But then he found out a pre-publication review outlet had run a rave.

So it was an ebullient man who greeted Nish and Dave at the door. He even hugged them. "Nice to see you, too?" Nish said, taken aback.

Daniel led them to the deck and Lauren met them there with a breathing bottle of cab. They called it pizza and beer night only out of tradition. They'd met years ago when Lauren had bought one of Dave's paintings. You wouldn't know who was the artist and who was the banker—both were clean-cut and conservatively dressed—but Dave was the one who later would drink too much, rant about the commodification of something or other, and retire to the backyard to smoke a hand-rolled cigarette. Lauren adored them both. "We just got a bit of good news," she said, wanting to explain Daniel's good cheer. "The first review is in, and it's fabulous."

Nish shouted, and Dave clapped. Because they were from worlds completely different from Daniel's, they could simply be happy for him. There was other news too: a conservative pundit had used a Wall Street Journal column to praise the book, which was poised to become a rallying cry for those on the right, left, and center who feared American retreat from the world. Not that there was a chance of retreat, a fact she'd have gathered even without Christos Kosco's tutorials. The truth is, Daniel's pro-Americanism had never sat well with her. It was in her very first month of grad school when she'd diagnosed the United States. Inflated sense of own importance, lack of empathy, overconfidence masking a weak ego, need for admiration: a textbook case of Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

"Okay, okay, simmer down," Daniel said. "I mean, Booklist: who gives a shit? But at least it makes me less worried reviewers will want to take me down because of Obama. This reviewer actually paraphrased Obama."

"Of course," Dave said. "Critics are cowards."

The doorbell rang and Lauren went to get their usual: large mushroom and onion, medium sausage and pineapple, Caesar salad. She paused on the way back. Dave had stood up to emphasize some point, and Nish and Daniel shared a look of affectionate skepticism. Beyond them, above the cliffs of the Palisades, the sky closed around a pinkish sunset. Gratefulness overcame her; nearly made her cry. This was a feeling she used to try to conjure, but it came only of its own accord. So many months had passed since its last appearance, it felt like an epiphany.

"But look at me," Dave was saying, "I've gone and put the focus on myself when we should be talking about the new masterwork by Daniel Weiss."

"Nonsense," Daniel said. "Believe me, I'd love to think about something else. Tell us, what's going on with you guys?"

"Misery," Dave said. "Sheer misery. Nish abandons me till deep in the night."

"You'll be shocked to learn that's a bit of an exaggeration," Nish said. "I've started going to the gym, which puts me home at eight instead seven."

"Nonetheless," Dave said. "By then my creative energies are long spent, so I find myself drinking and watching cable news."

"Oh, don't do that," Lauren said.

"All ISIS all the time. Terrifying, and yet—I can't quite explain it—ISIS just doesn't seem real. I can't help thinking they're a product of our imaginations, our nightmares."

"Jesus," Daniel said. "You sound like Lauren's new client. He's a conspiracy theorist who claims to have been in the CIA."

"How do you know he wasn't?" she said, trying not to sound angry. "He's actually quite smart about the Middle East."

"Even if that were so," Daniel said, "it doesn't mean he was a spy."

"I think he's telling the truth," Lauren said, "and it's kind of my job to know."

"Isn't there a way to find out?" Nish said.

"Just drop it," Lauren snapped at poor Nish. Lauren's hand shook as she lifted her glass. She wanted to break it on the table and slice up Daniel's smug face.

The conversation carried on but without her. She focused on stuffing herself: overlarge bites of the sausage and pineapple, swigs of wine.

Sheera came home. She paused by the sliding door and waved. They all looked at her through the glass. "She's lovely," Dave said.

"Very independent," Daniel said. "Third child. There's something to be said for neglect." This was only partly true. The larger truth was Lauren, opposed to the smothering style of modern parenting, had given all the girls more space than was typical. She didn't point this out because it would come out hostile and she'd already soured the evening. She shoved down another slice and excused herself.

Upstairs Sheera was lying on her stomach in bed, texting. This was the cleanest room in the house, and Sheera herself, in shorts and a tank top, looked immaculate. Lauren lay down next to her, placing her head by her phone. "Must you, Mom?"

Her daughter's flowery scent made Lauren consider her own odor. She blew her breath against her palm: oniony, winey, awful. "Who are you texting with?" she said.

"Santa Claus."

Sheera would return to her. The third time around, Lauren was able not to worry. Still, the distance hurt. Turning onto her stomach, Lauren burped. "You're disgusting," Sheera said, pushing Lauren up onto her side and almost off the bed.

And disgusting was how she felt: indulgent, gluttonous. She needed to fast, atone. She was meant for a life of selflessness. A nun's life but with sex.

No, if she'd been meant for such a life, she'd have lived it. Lauren's mother had been a teacher and activist. Two thousand people were at her funeral, celebrating a life of good works. Lauren's life was a spa by comparison.

But she'd become a therapist because she'd wanted to give. Or: Psychology had interested her and she'd thought she'd be good at it. And she was.

C: There is a degree of, I don't want to call it paranoia—there is, I would say, an exaggerated sense of people's interest in me.

L: That's not unusual with anxiety.

C: The other morning I walked in to a coffee shop, and everyone turned to stare at me.

L: I see.

C: What?

L: Well. I'm sure they weren't staring at you to the degree you felt, but you're certainly striking looking, especially in this day and age.

C: Ah. I look like an Arab. Ironic.

L: Maybe you'd feel more comfortable if you changed your look.

C: Yes, it's time. I'm going to shave, cut my hair.

L: Ok.

C:

L: I'm glad you're pursuing ways of alleviating anxiety, but it's also important, as we talked about, to address deeper issues.

C: I talked about my mother.

L: You've said barely a word about your experiences overseas.

C: I told you, I reject the premise.

L: What do you mean?

C: You think there is guilt.

L: No. I think your—you called them extreme experiences—had an impact on you.

C: Let's see. [scratches beard] I'm at a prison in Iraq. I'm overseeing interrogations. It's not my area of expertise, but there I am, directing recruits and contractors. Ignorant kids for the most part. They want to stick guns in mouths because that's what they saw Jack Bauer do. But I'm not a proponent of torture unless I want to send a message.

L: What kind of message?

C: You know: we own you. But torture is a bad way to get good information. I prefer a nuanced approach. On one occasion we are questioning a teenage terrorist. I instruct a female guard to strip down and taunt him in sexual manner, grind up against him and so forth. The plan is for me to swoop in and save him from this experience and win his trust. Good cop, bad girl, I call it. But this boy has an ejaculation situation. There is an emission into his underpants, and this horrifies him. It's perhaps the first time in his life he has ejaculated, certainly the first time in the presence of a female, and he has a conniption. He screams and pulls out his hair and punches himself in the head. I let it go on for a while, but then with a nod, I tell a guard to move in. He beats him with the butt of a rifle and kills him.

L:

C: That was one incident.

L: That's awful.

C: An unnecessary incident, yes. And my fault. It was poorly executed.

L: If you don't feel guilt, what do you feel?

C: There is sadness—and a sense of frustration. But it comes with the job, and you need to manage it. Things often don't go as planned, but you understand there is a method to the madness. The madness is part of the method.

L: What do you mean?

C: Chaos is sometimes a desirable outcome, and in this context collateral damage is inevitable.

L: Global domination doesn't come easy? That's how you put it a few weeks ago.

C: Correct.

L: Let me offer a hypothesis. Tell me what you think. You tell yourself you helped your country for the purpose of justifying your actions to yourself.

C: Incorrect. The fact I was helping my country did justify my actions.

L: But what you did in Iraq didn't help the United States.

C: Incorrect. Not everyone has the stomach for what is necessary. People like your husband—in order to accept violence, they convince themselves it's for the good of humanity.

L: I must tell you, that offends me.

C: What do you think of his new book?

L: I haven't read it yet.

C: Why not?

L: He cares deeply about humanity.

C: Not that much, believe me. Not that much.

L: Enough about Daniel, okay? No more mentioning him. He's off-limits.

C: Understood.

L: Let me ask you, Christos. You take a slightly—let's not call it paranoid, but you seem to believe there's a plot, a conspiracy, by which the United States exerts control.

C: It's not a conspiracy. It's out-in-the-open.

L: Who's doing it? Who's behind it?

C: You and your ilk.

L: My ilk? Is this about my kale again?

C: Rich Americans demand plunder.

L: You're exaggerating my wealth, I promise you. I'm not even in the one percent.

C: Globally, you're in the .00001 percent.

L: I know that. Do you think I don't know that?

C: Knowledge is of negligible importance. My best boss told me intelligence is 17 percent acquiring information and 83 percent making connections. High-quality intelligence work is performed by people who sit at their computer and make connections.

L: Is that what you do? Sit in front of your computer all day and make connections?

C:

L: Were you really a spy?

C: There is a lack of trust here.

L: I'm sorry, Christos, but for this to be productive, I need to have absolute confidence you are who you say you are.

C: Fuck you, Doctor. Fuck you in the fucking face. [gets up, walks out]

With an electric razor at the ready, I take the scissors to the beard, and the effect on the emotional state is nearly immediate. I experience continued psychic improvement as I shave down to my skin, so I also use the electric razor on the hair on my head and cut it short, one notch above a crew cut. Having left my mustache intact, I discover I resemble an older, heavier version of the brilliant dead singer Freddie Mercury. Mimicking Mercury as seen in the video for "Another One Bites the Dust," I spread my arms and try to lift my knee to my chest. It occurs to me the mental/emotional improvement may also be due to my not taking an Ambien last night. I did not sleep, not a second, yet I feel more clear-headed than I have in three weeks, and with my restored mental acuity, I formulate an operational plan. It strikes me initially as solid. To complete my new look, I put on a black t-shirt and a NYPD baseball cap I purchased for a reason unclear until this moment.

There is nervousness as I open the front door, but I feel able to manage it, to get "on top of it," perhaps even channel into the op. The old man who spends long hours on his porch next door looks at me and fails to realize I'm the same person as the bearded person, and the excitement of being undercover nearly makes me laugh.

The car radio is playing "Killer Queen" by Queen and it is difficult to impossible not to see this coincidence as meaningful. As I drive toward the Cross County Parkway, I try another Freddie Mercury-style knee-rise but hit the steering wheel.

I decide I'm too "giddy" for the mission, so I instruct myself to "sober up" and to facilitate this process I choose an alternate route that will, in nine to thirteen minutes depending on traffic, take me past the apartment by the Cross Bronx Expressway where I lived from the age of six to fifteen. It's the kind of building drivers-by point out to their car-mate(s) and say, "Imagine living there" or "I wonder who lives there." I did. I lived there.

The building is approximately 30 feet from the raised highway, but from this "vantage point" it appears close enough to spit on. I drive slowly and zero in on the window of the bedroom I shared with my brother, where I would try to fall asleep to the sound of traffic. Pretend it's normal. The household was not a good place for children. My father spoke rarely, yelled frequently, and had a defective digestive system producing "silent but deadly" emissions that made my brother cry. My brother cried often and gnawed his fingers till they bled. Thomas was the "sad" son and I was the "happy" one.

I dial Dr. Brown-Jonas's number, and when her voicemail picks up, I say, "This is Christos. Please, please call me as soon as you can."

This was the worst kind of party to host. Lauren felt all the responsibility but had no control. Success depended on who showed up. So far, the sparse crowd was too young—publishing house interns perhaps—and too old—their neighbors the Colemans had brought friends even more ancient than they were—and too white. A party for a book focused on the Middle East should have at least a few brown faces and a downtown event, in any case, shouldn't look like this. Instead of guzzling sangria by the buffet, Lauren should have been making the rounds. On the other hand, Daniel had the pleasantries covered. He glided around, making repartee. He always could rise to the social-promotional moment.

When she saw Dave she almost ran to him. "You look radiant," he said.

She spun around and realized mid-twirl she could fake her way through this. "Follow me," she said, heading for the bar. Dave ordered an Old Fashioned and she joined him, realizing wine wouldn't do the trick. "I'm sorry about the other evening," she said.

"I should thank you. For a change I wasn't the one who sent things sideways."

"I think Daniel's probably right. My client just doesn't seem like someone who did horrid things. At first I thought he was repressing it; now I think he's faking it."

"So he's a kook, not a spook."

"It would seem so, yes."

"Maybe he's a sociopath."

Lauren smiled, but this was a possibility she hadn't properly considered. She tended to believe everyone was reachable. "I think he's just fucked up."

"Is that your clinical diagnosis?"

"Majorly fucked-upness disorder, characterized by being bonkers."

"What's the diagnosis for him?"

She looked to where Dave was looking, and there, in all his mustachioed glory, was Thomas Friedman. "Oh my," she said. "Hyper douchebag syndrome." Flanked by a young man and a young woman, Friedman was wearing a wide-brimmed hat as if he'd just come off safari. He was waiting with visible impatience to speak to Daniel.

"And yet," Dave said.

"Right? The glow of celebrity. I suppose I should go facilitate an introduction."

But before she got there, Daniel had disentangled from a group of well-wishers and received Friedman with impressive nonchalance.

The place had filled up. She saw an Arab-looking man wearing bifocals and what's his name, the New Yorker writer who, like Daniel, had been one of the thoughtful supporters of the War in Iraq. But the person she was gladdest to see was Marge Rowell, Daniel's ex-Voice colleague, an unreconstructed socialist, someone who hadn't sold out.

As Lauren made her way to Marge, a man who looked familiar blocked her path and put his face too close to hers. Another mustache. Baseball cap. He was crudely handsome and had an antiseptic smell. "Hello, Doctor," he said.

She choked back a gasp and, inspired by Daniel's example, managed to act blasé.

He looked ten years younger. Big pockmarks on his cheeks, an English muffin face.

"Christos," she said, "what are you doing here?"

"I need to speak to you."

"You should've called."

"I did."

"What's wrong? Is it an emergency?"

He stepped back, with one hand on his hip, looked past her. Not just his appearance but his entire aura had changed. "So this"—he waved his arm—"this is your world."

"No. But it's a special evening for my husband and my family, and to be frank, I'm a bit aggravated you're intruding on it."

"I need to speak with you."

"About what?"

"Let's find a quieter place. You don't want to be here. Let's go."

"Christos, I can't, I'm sorry. I'll see you at your next session, okay?"

He glared at her, making his eyes big, then pretended to bite into his forearm—no, he actually did. She took his arm and pulled it away from his mouth. "You need to take care of yourself," she said, the shakiness in her chest entering her voice. "Please leave here and go straight home. Can you promise me you'll do that?"

"Help me," he whispered. "Please."

"I will, Christos. I will do everything I can to help you, but I can't right now."

This seemed to mollify him. He backed away, turned. She watched to make sure he left. She went to the bar for another drink, bourbon straight, which she finished in two gulps. She saw another famous face: Fareed Zakaria, pundit and plagiarist.

A call had gone up for her. She was ushered through the crowd. Into the middle of the circle she went. "Here she is," Daniel said. "My wife, my rock, without whom no book would exist." People clapped. She waved. More than a hundred people here. Zakaria's hair was extraordinary. She made eye-contact with Marxist Marge and blew her a kiss. She didn't listen to Daniel's little speech but noticed when he started slurring. She put her arm around him and pinched his back. He picked up her signal, wrapped it up. The crowd dispersed to reveal Friedman bent over the buffet, poking something.

The music got louder. Nothing she knew, but the beat was right there, easy to hook onto. She looked for Dave. She wanted to dance barefoot on one of these plush rugs.

Last's night relief and joy lasted perhaps six seconds into the morning. Then her headache took over. Nothing of value had been accomplished at the party. A bad outcome had been averted, that's all, and now here was her life again, in all its grayness. Eight o'clock. Daniel would already be in his office. He worked every morning regardless. It was a point of pride with him and by itself nothing but admirable. She couldn't imagine writing right now, or doing anything beyond sipping coffee in the daybed. Jesus, she'd smoked cigarettes.

Downstairs she discovered Daniel hadn't made coffee and had finished yesterday's. Her anger left her trembling. To steady herself she put her hands on the counter. Just make it through the day. Make it through the day and go to bed early.

The doorbell rang. Through the window in the front hall she saw a police car. The doorbell rang again. Had she hit something on the way home? No, they'd taken a taxi.

When she opened the door, the cop farther from her said, "We're looking for Doctor"—he looked at a piece of paper—"Brown-Jonas?"

"That's me."

"Do you know a person named"—checking the paper again"—Christos Kosco?"

"He's a client of mine. What happened? Is he okay?"

"You're a psychiatrist?" asked the other cop, younger, with purple razor burn on his white neck.

"A psychologist. What happened?"

"When was the last time you spoke to him?"

"Tell me what happened to him."

The younger cop walked back down the walkway, and the older one, who had a bruised-looking Karl Malden nose, stepped forward. "Mr. Krisco is missing," he said.

"Did he kill himself? He killed himself, didn't he?"

"We're not sure what happened at this point."

"He killed himself."

"We're investigating that possibility, among others."

Her knees gave out, and the cop caught her by the arm. She turned away because his breath smelled like garbage. It got into her mouth, the smell, and then she was throwing up, heavy heaves. Orange stew on the lawn, late-night fettuccine Bolognese.

The cop asked if she was okay. She spat and nodded. "When you're ready," he said, "we'd like to ask you a few questions."

She sat down on the steps and the younger cop moved forward. She wondered if their maneuverings were by design, a way to try to get her to talk. "How'd he do it?" she said.

"We can't tell you the details of the investigation at this point. He left this in his car." He handed her a photo. It showed Christos with a group of armed Arabs. On the back he'd written, "Now you have blood on your hands, Dr. Brown Jonas. But then you already did. Thank you for caring. Damn you for not caring enough."

"Does the photo mean something to you?"

She was crying but felt nothing; it was like bleeding painlessly. "He was in the CIA."

The cops looked at each other. "You know this for a fact?"

"I do now," she said. "I need to go lie down."

"Wait," said the younger cop. "We have more questions."

"Not right now. Please. Call me later."

"Did he have suicidal tendencies?"

"I said, not right now"—she raised her hand to the cop, quieting him—"I just found out a client of mine killed himself, and I'm not sure what I'm permitted to tell you, and I just threw up, you may have noticed, so leave me alone."

She sat there and waited for the cops to drive away. Then she saw little Alex Shin watching from across the street. The kid had probably seen her vomit. She pushed herself up and walked toward Alex, having to limp for an unknown reason.

"It's okay, Alex," she said from the edge of the lawn.

With huge eyes he stared at her. He was wearing pajamas and cradling a mini soccer ball. Slowly she approached. He was four, maybe five. She'd watched him once when her mother had gone out. It was crucial he not fear her now. She lowered her hand toward him, and he let her put it on his shoulder. She smiled and said, "You see? Everything is fine."

He turned and ran up the steps. He looked back from the doorway, then shut the door.

Crossing the street, her whole body aching, she started to cry again.

She went upstairs to tell Daniel but stopped short of his door and sat down on the floor. Soon he would emerge for another cup of coffee. He would expect it to be made. It never wasn't.

He wouldn't notice she was upset. She would tell him what had happened. He would say Christos was crazy and there was nothing she could've done. She would tell him about the photo. He would say a vacation had inspired his fantasies.

His smugness would be crushing. She wouldn't be able to bear it. She would bear it. A week after he asked her to marry him, he told her he was married to his work. She told herself she loved his passion and that being with a writer was infinitely more interesting than being with a lawyer or the like. When she was 30, they decided to try to have a baby. But she secretly kept taking the pill. A baby, not marriage, was it, the real commitment, the point of no return. She wasn't ready. She would get ready. They were living near Columbia. She went for runs in Riverside Park. She would summon strength, defeat doubt. Back then she was of the belief fears were to be worked through, not listened to. Now she was 58 and sitting on the floor and dreading the sight of her husband's face.

But she was every bit as self-centered and selfish as he was. She had chosen tapas with Thomas Friedman over helping a desperate man, and now that man was dead.

In the bush I've used my knife to carve out a sitting space. I've been awake for 53 hours, yet I feel clear-headed. For an espionage officer of my experience, this mission is "child's play"—the precautions I've taken (i.e. fatigues, mud smeared on my face) aren't essential—but going deep undercover has restored my equilibrium.

The realtor propagandized, as realtors do. The house, although on a cul-de-sac, isn't a "hideaway." Three other houses are nearby, including this one in whose bush I'm stationed.

And now here, more than an hour earlier than I anticipated, is the police car. Through my binoculars I see the officers get out. They're both plump and pink, mediocre like most cops, but perfect for my purposes, neither stupid nor smart.

The Doctor answers the door, looking pale and ragged. The cops would be asking her if she is Doctor Brown-Jonas and if she knows a Christos Kosco. She speaks, and what she hears in response makes her rub her face, the understanding setting in.

A small boy, part east Asian with "doe eyes," has appeared on the lawn beside me. He must've come around from the back. He is approximately ten feet away, but he doesn't see me and won't see me. The boy and I watch the Doctor vomit. I put down my binoculars and look away. Without kindness there is no betrayal. Without a bond there is no abandonment.

The boy drops his ball and kicks it by accident. When he's picked it up again, he's moved forward, and I can no longer see his face.

She is crying, having read my note. You brought this upon yourself, Doctor.

She raises her voice, nearly yells at the police, perhaps telling them to leave her alone. Her assertiveness in the face of armed agents of the state is a product of her "social station." The police work for her, as I once did.

The older cop "rolls his eyes" at the younger one before getting in their car. As they drive away, the older cop studies the photo of me with Syrian "rebels."

The boy shuffles backward a few steps because the Doctor is walking toward him.

"It's okay, Alex," she says, and I can't help but take comfort in her soothing tone. She is limping, and it appears a blood vessel has burst in her left eye. But she is "bearing up" for the boy. When she puts her hand on his shoulder, warmth flows through me, and I close my eyes. "You see?" she says. "Everything is fine."

The slam of the door wakes me from my second of sleep. There was a Baghdad kite festival in my dream. The boy has gone inside.

The doctor is limping away. I snake-slide toward the woods, where I will remain until dark, at which point I will proceed toward my house. There I will formulate a plan for solidifying my death, which will enable me to thrive in Westchester County.