Image courtesy of British Library Photostream

I talked to some who said you were never there at all, not in any way that matters. They said you were an urban legend. They said everyone knew someone who had a cousin who saw you perform, met you, dated you, slept with you, whatever. They said even if I found the person you were based on, it would be looking through a mirror, darkly, that I would have to squint extra hard to make it seem real. They were ignorant, Principessa. They were wrong.

The first time I saw you was in three photographs. Two were in a file thrown into a storage box; the archival label read "Fairs, Carnivals." One was of the full cast: a blockhead with a hammer and nail; a tattooed man wearing only shorts and ink from head to toe, his body telling a story only he could decipher; a short, overweight man with lobster claws for hands; a curly haired bombshell holding a sword; a wolfman standing next to you, his arm around your waist, tongue out as he leered down at you; two men above you lying comfortably along a high wire; all of them vying for the camera but obviously enjoying themselves. Right in the middle of the shot was you. You had two tiki-torches jutting up from behind your shoulders like the crossed swords of an action movie hero, a bandolier across your chest which, I would later learn, held a Zippo and a series of dangerous items—flasks and vials of wood alcohol or 151, some with chemicals to produce colored flames; also fireworks—strobe bulbs, sparklers, ground spinners you would hold in your hand as they screamed and whirred and people gaped with wonder. Your shoulders were set forward, and the strength of you was so apparent, and you stared straight at the camera like you knew it was there to stare back.

The other picture, a portrait of you with the same date written on the back in a blue magic marker matching the color of your hair, "Summer, 2001." You're standing in front of your banner ad and striking an identical pose: a semi profile, your torches lit and held in one hand, your back arched, your mouth toward the flame as though preparing to spew fire. The banner, eight feet tall, garish in its blue highlights and bursts of orange and red flame, hangs skinny from a concrete wall. Because the banner was bigger, because it exaggerated your features (the way everyone and everything did), the details of you were more apparent—your blue hair, the nostril ring, your red leather pants and matching corset top. There's a candle to each side of you, and the smoke rising from those candles drifts into Art Noveau letters clinging to the borders. They read, "Principessa Di Fiamme, Princess Of Flames."

The image of the troop, I would learn, was somewhat famous in its own right. The wolfman was part of a renowned family of wolfpersons, all of them with congenital hypertrichosis. He was well regarded amongst freak show performers. I tried to contact him, but the wolfman was beaten to death outside a construction site in a smallish city in Mexico long before I went looking.

The box with the photos was in a library in Philadelphia. "Virtually everything in long-term storage is local history stuff, mostly newspaper related," the librarian said. "We still have microfilm—you could use the date to go through them and maybe find a corresponding article."

I had gone to the college because they had old records from the fair that passed through over the summer. I had been researching for an article about the evolution of entertainment in the area. Two hours later, when I found an article about the county fair, there was a third image. It was taken during your act, your torches held high and your head tilted back, a burst of flame larger than your 5' 3" frame growing out of your mouth, caught forever on 35-millimeter and visible to me in the glowing silver of microfilm. The article didn't mention you or the freak show at all.

I talked to some who said you must have died, because it couldn't have been a healthy lifestyle. I thought, maybe they're right. But what did it matter? I was committed. Something in the image of you, of your eyes focusing into the camera, of your posture, of... something. I've learned since I wasn't alone in the need to be in your life. You'd come and gone for so many, been so important to them, been a muse and a siren and a love song. Yes, it was strange to search for you as long and as hard as I have, but the mystery of you needed solving, even if the end was a stone in a cemetery.

The newspaper was long defunct, but I tracked down the writer working for a small business paper in Atlanta. I emailed him a scan of the article, and he replied quickly. His email read:

Yes, I remember this. I'll tell you what I know, but it's not much.

I went to the fair with a photographer to do a write up. He was kind of a jerk and we didn't get along so we split up right away. You can see I wrote a very standard piece, a lot of "fun for the whole family."

The next day the editor called me to his office and showed me the negatives. They started off normal, but then there was a picture of this girl, and then it was just picture after picture of her. It was creepy. We went with one of them in the end, but the editor chewed out the photographer.

The next year that group wasn't at the fair. The photographer was devastated not to see her. Apparently he'd been carrying a torch (pun intended). I really don't know anything else about the girl.

Sorry I couldn't be more help, but thanks for sending the article and for the memories. Those were better times for the kind of writing I do!

Good luck with your search.

Though his email provided no answers, I appreciated the info. I printed it out and tacked it next to the Eastern Seaboard map on my wall where'd I'd drawn the fair's route in red marker.

The photographer's family lived in Albuquerque. I spoke with his widow on the phone. He had been a drunk and had died from liver failure some years earlier, she said, not so much detached as just not emotional about it. She said she was better off without him. When I texted her the pictures of you, she said, "That asshole. That makes sense. Around that time he started asking me to wear a blue wig in bed."

I talked to some who said the freak show was everything to you, Principessa. There are other pictures of it online, as well as casual pictures of you and the other performers: one of you holding a beer bottle at your hip, rapt in attention to a story being told by another; one where you're standing behind a guy who's sitting in a chair, you're bent at the waist and your arms are wrapped lovingly around his neck; one where you're holding hands with a girl who had straight bangs and a leather jacket, both of you turned to the camera in front of a Ferris Wheel, but she's turned to kiss your cheek right as the camera snapped the picture—a kiss evoking young lovers in 50s nostalgia movies—and nobody looking at it would doubt she loved you; so many of you breathing fire.

These images weren't much use. They chipped away the ethereal vision of you, but they couldn't help me find you. They were dots, unconnected to a line.

The tax records for the fair were in an office in Sarasota, Florida. From there I tracked the freak show to nearby Gibsonton. Their city hall was a lot of help. Small town locals love to tell stories, and they were happy I was interested. The clerk called over to the archive and the local history museum, and soon the office resembled a coffee klatch. We were moved into a boardroom to get us out of the way.

The official name of your freak show was "Southern Freak Show and New-Age Extravaganza." One of the employees, a former sword swallower who performed under the name Jessica Jubilee, lived in town. A clerk was friends with her. Jubilee came down within the hour. She was the woman in the photo from the Southern Freak Show, the women with the sword, and all these years later she'd barely aged at all. Her skin was creased around her eyes, but even wearing jeans and a plain blue t-shirt, even without makeup, she was still a bombshell. Her movements were graceful, and she had an air of humor. When she walked in, everyone smiled. I immediately imagined you two working together, how there must have been competition. I didn't know you well enough yet to understand how impossible that was.

Looking down at the photos, running her fingers over the front of them, Jubilee said, "Oh, these were ages ago! Look at us!"

After giving her a moment, I asked about you, the girl with the blue hair and the torches. "Yeah, the Princess of Flames. I haven't heard of her in a dog's age. Her real name was Leah Brooks. We were on the road together for two seasons."

"What can you tell me about her?" I asked, thrilled Jubilee was so forthcoming.

"She was great! She was a problem for my act, actually. I was usually the sexy one. I was younger then of course, and sword swallowers have a lot to work with as far as sex appeal goes. But she just came along and lit the room on fire. I wanted to hate her, but honestly she was so sweet and so damned endearing. She was the darling of the show. We all loved her." Turning her face back down to the picture, she said, "Wow, it's hard to imagine where she would be now. I mean, it's hard to imagine her getting older at all. In my mind, she's always exactly like this, just timeless."

I, too, struggled to imagine how the years would have presented themselves to you. Would you have aged hard from life on the road, your body sinewy, your face sunken deeply with lines, you hair brittle from years of dying? I think I assumed that at the time. But I would come to believe the years might have been as charmed by you as Jubilee was. The more people I met who recounted your stories as though they were still back with you, the more I realized everyone felt that way. The timelessness of their stories must have matched up to someone, must have equaled a timelessness in you. You were a force of nature, and nature takes a different view of time.

"You have no idea where to find her now?" I asked.

Jubilee laughed. "See? Even now, it's all about her! No, I have no idea. But Matty might. Matthew Williams. He's the tattooed man in the photo. They had a thing. If anyone knows where she is, it's him."

I talked to some who said you're still famous in some circles, that you hold court in a penthouse in Manhattan, or a ranch style in LA, or an apartment in Shanghai. Matthew Williams, the Southern Freak Show's tattooed man, would have known if that were true. He lived, appropriately, above a tattoo parlor. The building was low income and pretty squalid outside, its off-white stucco stained dark with time and wilting in the tropical Florida sweat, but his apartment was clean and tastefully decorated. The walls had pop art posters from Warhol and Lichtenstein, and framed photos of a much younger Matthew Williams than the one who opened the door.

"You must be the reporter. Come on in."

He was wearing a t-shirt, and his tattoos, mostly traditional Sailor Jerry types—ships and mermaids and waves, anchors—flowed down to the bones of his knuckles and bled upward from his collar onto his cheeks, across his nose and forehead. They were faded but probably looked old the day he got them. In the picture from the freak show, he had been shaved bald, but now he had smooth, light brown hair and a curly beard. I think he'd be happy if I added he still looked great, Principessa.

He offered me water and brought a San Pellegrino with a slice of orange, saying, "The heat down here gets to a lot of people."

When I asked about you, he smiled and spoke openly, "We had a romance going, and when the freak show closed, we left together. We had some cash saved, but it was gone in six months. I got a call from a friend in London who said there was a scene there and that we could work in circuses traveling Europe. So off we went to London and hooked up with a Spanish circus called Gran Circo Mundial touring Great Britain.

"It was her act that got us the job. Tattooed men weren't anything shocking even in those days. I worked the ticket booth and chatted up people in the crowd before the shows. But she was a central act, and what an act! She was constantly working to improve it, finding obscure videos of fire-eaters or blockheads or sword swallowers, trading tips and advice.

"And the show really used her, too. She was out walking around town putting up posters and advertising, and she brought people in. She made it all seem so fun. The Southern Freak Show, we did our best, but it was a tiny operation. Mundial was big, and they loved her. I was just tagging along, but that was alright. We were with them a whole season.

"Then Mundial went back to Spain. We toured midsized towns and took a seasonal break, and Principessa and I were broke again. My brother in Boston hooked me up with a straight job at a factory. I didn't like, it but I could see the writing on the walls as far as my profession was concerned. Principessa stayed in Europe. After that we emailed for a while, but we lost track of each other."

"Why do you use her stage name?"

"She was using the name Leah Brooks when we were in the freak show, but I never thought it was real. She sometimes didn't answer to it right away. It was on her passport when we went to England, but I didn't buy it. Then, a few weeks after we were there, before we left London, she asked me to start calling her Luz Botrero—she said it would play better with the Spanish audience and the roadies. And she had new papers for it, a license and a passport. Really convincing ones. The passport had stamps and was bent up and everything. The only way to tell they were new was that she had her tragus pierced the same day—it's that little nubbin sticking out in the center of your ear—and it was swollen enough you could see it in the pictures. If no one noticed the unlikeliness that she had the same swollen ear in her license and passport, there would be no way to tell they were fakes.

"I don't know why she would have wanted a new identity, or what her old one really was. I wanted to know, but we were carnies deep down, and you just don't pry into people's pasts without invitation. I doubt she ever invited anyone. So I don't think I ever knew her real name, but I knew Principessa was real."

"Would you know where to find her?"

"I've only heard rumors."

He told me the rumors. That after Spain she went through Morocco and eventually to South Africa, then Australia.

"A friend swore he saw her getting off a cruise ship. He showed me a picture of the back of a women's head. I don't think it was her. There were so many rumors." He paused, and the silence grew long as he looked beneath my eyes. "We all loved her, I suppose."

I think he wanted to look wistful telling this, but he looked sad. Sad and old, his bright eyes dimming in his ink-darkened face, his nice apartment in a rundown building, his lost love. He looked down at a tattoo on his arm, and I put it together. All the Sailor Jerry girls, the hula dancers and mermaids, all of them had blue hair. All of them had piercings. They had been modified over time to look, at least a little, like you.

"All these rumors. She's still famous around Florida, but no one knows where she ended up. If anyone did, I would know it. I'm sorry I couldn't be more help."

"Thank you for your time."

"Of course."

As I left Matthew's apartment, he was already out of mind. Another note on the board. Another end. A search for a probably fake 20-year-old passport for Leah Brooks, another for Luz Botrero.

I talked to some who said you had many names but insisted no one knew your real one. Some of the people I talked to heard a rumor that even you didn't know your real name, that you had amnesia, that the wood alcohol you used for breathing fire had cooked down your long term memory, or that you hit your head one day when you were visiting a circus as a girl and had woken up there with only a blankness of your life before, that you were just... born to this life. Other less far-fetched rumors included your mother working for a circus, and of course that you ran away from home as a teenager—maybe fleeing abuse, maybe just bored, who knows?—certainly no one would pry—and that you, like so many others, found your place on the road.

The search went on. Leah Brooks never returned from Europe, but a particularly enterprising IRS employee, in exchange for $200, connected Luz Botrero to an address in San Diego and to the owner of a Mexican restaurant. A Lita Barraza had performed at a number of events there around the time the name Luz disappeared from record. Lita's DMV photo, well, wouldn't you know it?—She looked just like Leah, just like Luz.

Alejandro Rodriguez, the owner of the restaurant, is still alive, Principessa, if now very old. He chats up customers while his daughter Isabella runs the place. They both smiled, remembering you.

The restaurant is still active. Portraits done in mosaic talavera tiles hang heavily around the walls, next to as many or more black velvet ones—of Mexican presidents or heroes, of Carlos Santana and Frida Kahlo, a Mexican wrestler, a famous bullfighter. Do you remember?

Alejandro, sitting in a booth with me, his black hair graying and his eyes piercing, told me, "She worked events here for two years. I met her on a cruise ship in the Caribbean. She performed in a dance revue and walked around entertaining people and doing magic tricks. She hated it. 'I'm no dancer,' she told me one night when she was doing a walk through at the main bar. 'They make me take out my jewelry, and I have to do hair and makeup their way. Anyway, I've done it for over a year and I'm bored. But it's a gig.'"

"I had a friend at the time running a talent agency hiring out all kinds of freelance performers, so I gave her his info. A few weeks later, she just showed up at the restaurant, going by Lita. When I asked why she changed her name from Luz, she insisted I must have had too much tequila when we met, and she winked. Too much tequila. Ha! It didn't matter. In San Diego, sometimes names change. It's unimportant."

"Did she get a job with the talent agency?"

"Of course. Who wouldn't give her a job? She worked all over Southern California, even Vegas. She used a corner of my office to keep papers and documents. She ate here often—always on the house—and when I had special events, she would work them for free, dancing and doing fire shows. We serve a flaming margarita, and she would light them by breathing fire, sometimes light five or six of them in one long row, like a dragon setting fire to the turrets on a castle. Probably not great with the Board of Health," he laughed, a big, booming laugh filling the room, "or the fire marshal for that matter, but the customers loved it."

"She did fire shows?"

"Si, when we needed them, but she did all kinds of things. Some days we'd need a fortune teller, and she'd show up dressed as a gypsy and read tarot cards. Once we needed a fairy to entertain kids at a party, and in walks Lita wearing a blue unitard with these colorful feathered wings, talking like a fairy in a kid's movie. She winked at me as she came in the door and spent the night doing magic tricks and painting kids' faces—she never broke character except for that one wink. But like the cruise, it wasn't the work she wanted."

"Why do you say that?" I asked, ready at this point for any answer.

"The freelance stuff was individual performers, and she wanted to work with the freak show again, or with a fair or the circus, something where the people were connected to each other. She told me all about it one day when she was here doing some filing, and then we shared some tequila and got to talking. Then maybe two months later, I came in and her papers were shredded. She left a post-it saying, "Muchas gracias por todos." Isabella was devastated. I thought maybe they had a fight, but Lita had come to her and said she got hooked by a talent scout for Cirque du Soleil in Vegas. We never heard from her again."

Isabella confessed to me that her father undoubtedly loved you, Principessa.

"I don't mean like that. He was old and loyal to my mother. His love for Lita was parental. If anything he wanted me to marry her, not that it was legal at the time. But I would have. I loved her deeply."

Isabella was tall and stood very straight, but when it was her turn to sit in the booth with me, she slouched, or leaned forward on her elbows. She talked about you for some time. She referred to you as the one who got away. Isabella said, "When Lita wasn't working, she was always with me. You can still see the bumps where we got earrings all the way down our outer ear cartilage—her idea." She swept her straight brown hair away from face and turned the side of her head toward me. The holes had long filled in, but the telltale bumps were there, a scar you left her with. "I think she loved me as much as she was able to love one person. But to her there were so many people. The fault may have been mine for hoping too much. I went through the whole post-break up depression thing. I cried for weeks. I barely ate. I thought I'd never forgive her, but honestly, too much time's passed for me to be upset about it. I hope she's well. I hope she remembers me as much as I remember her."

Alejandro's friend who ran the talent agency was dead and had left few records, though I managed to track down several other employees from the time. They all remembered Lita, all smiled when they heard her name, but Vegas was the best lead.

As I left the restaurant, I noticed, behind the host stand where Alejandro Rodriquez chatted with customers, there was a black velvet portrait of a blue-haired girl, a string of earrings running down her cartilage, against a background of flame.

I talked to some who said you performed in Vegas in Cirque shows, and even in the cabarets that had come back for a brief resurgence. No Leah Brooks was listed as a previous employee, no Luz Botrero or Lita Barraza. But a concierge at MGM remembered a blue-haired girl, piercings, tattoos, flames. He remembered her name as Lux and found it pretty quickly.

"Lux Brisbois, that was it. Most of the performers stick to themselves, but everyone knew Lux—the concierges, the bellboys, the dealers, the pit bosses, everyone. One night some of us got off shift and went for breakfast at the Tropicana, and wouldn't you know it but Lux was at our table. You'd see a high roller and Lux was blowing on his dice for good luck, or some old case of Vegas royalty, someone 70, 80, been on the tables for 50 years, would say, 'Have you met Lux?—Charming girl, that one.' She must never have slept to have been so popular."

"Could you put me in touch with some people she was close with, anyone whom she may have stayed in contact with?"

"I can do you one better. They shipped her off to École Nationale de Cirque in Montreal. A lot of the best talent gets shipped there for circus finishing school."

With so much to contain, I had tacked a world map to the wall of my home and added Montreal to the marked and dated places where you were. It also had pictures, addresses, post-its. The pinned strings and drawn arrows were spreading outward, ever bigger. The map of you had no center, and little in the way of boundaries.

Off to Canada.

I talked to some who said you stayed in Montreal, or at least in Canada. That you married a diplomat who had seen you perform, and through him you gained a name and lost your jewelry, that your hair was naturally blond, that you sent your kids to private schools, that you spent your time in Switzerland or the Seychelles. Others say you moved to France, working as a street performer outside Notre Dame, that you fell in love with a mime, that your wedding was silent and beautiful, and that's why no one ever heard from you again. I couldn't tell if this last story was true or just an elaborate pun at my expense.

Others said you moved to Paris to work Cirque d'hiver, who were impressed enough they paid your moving expenses and gave you cash up front, but that in a coups you joined up with the Romanes Cirque—the Gypsy Circus—and starred in their show. They say you had a brief romance and falling out with a trapeze star, a violent, jealous man, and you had to be smuggled out of the country to safety in Romania. This, too, sounded unlikely.

Others said you simply met someone, someone normal, a girl who worked in a coffee shop maybe, something like that, and you looked at her the way people looked at you. That she was more to you than the stage or the act. That eventually you moved back to the United States, to some medium-sized city, Austin or Reno or wherever, and you settled into a quiet life and were no longer restless. I liked this story more than the others, Principessa, but I doubted it.

Franci Desroches, the director of clown arts at École Nationale de Cirque when you were there, was not easy to get a hold of, retired as he was. But once I did, he invited me into his home. Franci looked like he'd worked for Cirque do Soleil, though he was less intense than I expected. He was short, and the muscles of his arm were tight and showed veins running their length. I could easily see him hanging from a ring or boosting another performer. Sitting in his yard, a small mutt of some kind close under foot and cups of espresso steaming at the table, he told me, "Yes, I remember her. She trained with us. One day only a few weeks from graduating, she disappeared."

"After you called, I found some photos from the yearbook." He opened a folder and spread several large, glossy photos on the table. "I made these copies for you—no trouble at all—and you can see she's right here in the background, soaking up the whole image. The audience would have died for her. Had she finished, she would have been the star of the show."

"I gather she was, everywhere she performed," I replied as I looked over the photos, noticing the industrial earring that had been added to your collection.

Leah, Luz, Lita, Lux, Principessa Di Fiamme, again you. Always aware of the camera, always slyly looking up, smiling into it, taking the focus from anyone else in the frame, absconding with it. Other performers were in front of you, working. Others still were in the background, watching you the way you watched the camera.

Franci, pointing a finger at one photo, said, "See there, that's me, demonstrating a toss." He was holding juggling pins. Principessa was working with him, holding a set of her own. "She wanted to perfect juggling so she could juggle torches. She had an idea for flaming knives. I caught her practicing one night in the dorms, throwing a set of pins and timing it to swig from a bottle and blow it over the flame. She was just doing it, tossing, swigging, spitting, while other students stood around and watched. She disappeared soon after."

"Did she leave anything, a forwarding address?"

"No, nothing. But an instructor left at the same time, and we always assumed they ran off together even though he said he had to take care of a sick family member. He left a forwarding address." He pulled out a piece of paper he'd written the address down on. "It was in Shanghai. I'm probably not supposed to give you this, but I'm retired, so what do I care? I hope you find her."

Again, someone willing to help. Someone willing to give me information they shouldn't have. I could've been anyone. How did they know I didn't mean you harm? That you didn't owe me money? These people cared about you, but they were willing to assist a stranger in tracking you down. Why? I can only assume, Principessa, that they knew. That they felt the same way as I had come to feel. I suspect they wanted me to find you, so they, too, could find you, if only vicariously. At least in their imaginations. They all loved you, Principessa. They all love you still.

"Me, too." I folded the piece of paper and took the pictures, lining them up in my notebook. "Thanks for everything."

"Thank you, son, for the memories."

I talked to some who said Shanghai suited you, that you were still there. I had learned to disbelieve these stories.

The forwarding address was a small apartment away from the city center, owned by the cousin of the instructor you ran away with. The cousin still lived there, had always lived there. He showed me a picture, and it was you alright, still blue hair, a labret piercing added to your constellation of metal, still you.

The cousin didn't speak English, but he was so willing to talk he had a neighbor come over and translate for us. Through the translator, the cousin said, "I remember, of course. My cousin and Lan showed up unannounced."

"Her name was 'Lan'?" I asked.

"Yes. Lan Bu."

Of course it was.

"It was not her real name. She asked us to pick a local name for her. They had traveled Asia and spent their last money to arrive at my door. They threw cocktail parties lasting all night. They were sometimes picked up in a limo, and no one in this apartment block had ever been in a limo. One day the Minister of Culture for Shanghai came here with them, into my apartment! Sometimes the two of them would come home in the morning," the translator faltered here, and the two went back and forth. "Yes," he said, returning to English, "they came home... I think the American phrase is 'stinking drunk' and woke me up. I worked hard. They didn't work at all."

After a pause, he continued. "This sort of thing would normally upset me, and my neighbors, but it was difficult to be upset with her. She was always happy. There was something," the translator paused and thought for a few moments, groping for the right word, "infectious about her. Everyone wanted to be around her. They were family. I thought of her as family after only the first few days. I didn't kick them out. They were here over a year."

"Do you have any idea where they went?"

"She went back on the road. I think she liked all the partying because she liked people, but she wanted to work and in Shanghai it was difficult. He got a job in the city and stayed here for several months before he got his own place. He passed some years ago."

"Can I speak to some of your neighbors from that time, or some of your cousin's friends who might know her?"

"Of course. I'll see if I can help. But it was a long time ago."

"Any help would be great."

I talked to some who said you never left the freak shows at all, that some years you showed midriff and a belly button ring, some years bare shoulders, you back tattoo, large, of orange and yellow flames that curled around your ribs and curved down over your shoulder blades to lick at your collarbones. They say you worked with different groups all over, but that wherever there was a blockhead or a sword swallower or tattooed man, an acrobat or a wire show, there you were.

I tracked you more: to a hotel in Chang Mai, Thailand, a rumor about you Balinese dancing on a stage in the night market; slight but reliable evidence of you managing a community theater in Sydney, Australia; to an art collective in Argentina; a trail north through Valparaiso, Chile; east through Brazil; through Venezuela; a couple of years in Mexico City. The stories were the same. Friends, lovers, people who missed you, who heard rumors of you, exchanged memories of you, thought of you when they were drunk and maudlin, woke up sometimes in the quiet dead of night from a dream of you, gasping and shocked, for just a second lost in the past, with you again, then confused and distraught in a world without you, unable to return to sleep.

These people all provided pieces of the great puzzle that was you. They helped me to fill in some of the lines of my map, or to scratch them out and replaced them with more credible info.

Finally I tracked you to New York, to the manager of the Coney Island Circus Side Show, who put me in touch with Davey V. The map was a mess by then, a contradiction of dots and lines and post-its, tacks, photos. Even I couldn't follow it anymore. I was hoping, as always, I wouldn't need to for long.

Davey V was a human blockhead and former front man of the Coney Island show, big enough in his heyday that he had a beer named after him you can still buy at BevMo. Davey lived in Brooklyn. I knocked on his door unannounced, as instructed by a performer who said he wouldn't answer his phone anyway.

He opened the door, wearing slacks and suspenders, a waxed and curled moustache, and invited me in before I even told him what I was there for. There was an umbrella stand filled with exotic canes to the side, a wall with bowlers, newsboys, and top hats hanging on pegs.

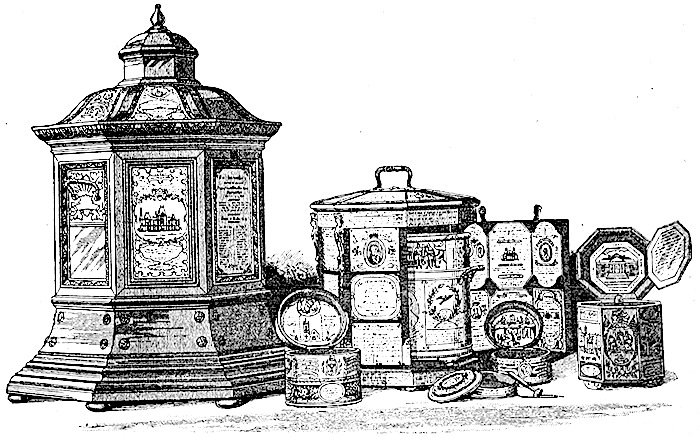

But mostly the house was a collection of freak show paraphilia—posters, banners, art, a museum to itself.

"Of course, Principessa. I remember her," he smiled to fill the room. "See how much?" He indicated a section of wall filled with you, Principessa. Playbills, promos, a post card with you on it. The centerpiece was the original banner I'd seen in the photograph, the real thing, eight feet of canvas, the colors still bright, the static image 100 percent you, 100 percent the lie you had ever held still at all. Seeing the shrine, my heart skipped a beat. Pictures, playbills, I'd seen those, but this was something more. Someone with this might actually know where you were. I quickly tamped down my excitement and turned back to Davey. "Leslie Baker, but everyone called her Les. She was great in our show. I mean, she captivated the audiences for sure. She also spoke a bunch of languages, and that really helped with the tourists. Let me see if I can remember... Italian, Spanish, Russian from when she worked for a circus in St. Petersburg. Some Mandarin. A little Thai. Native Hawaiian. She was from Hawaii originally, heir to a sugar and exporting fortune was the rumor."

"Always the rumors," I said, my voice indicating an eye roll, but also rising higher than I'd intended. I'd never heard any reference to where she came from before the Southern Freak Show. Her early life had always been impenetrable.

"Right? But I believe that one. She got the tiki torch thing from Hawaii. She was great on the show."

"You two were close?"

"Yeah, we were. We all were. They offered her center stage when I left, but she said she wanted to take a break." We were in his kitchen now, and he was pouring Manhattans from a shaker. It was two in the afternoon. Though it seemed an unusual thing, I was thankful for the drink. My pulse was beating through my veins. "She was thinking of doing a YouTube channel where she interviewed carny friends and did tricks, but, unlike most of us, she was never into social media. It made it hard to keep in touch with her, but she said it took time away from the people in front of her. I got it. We were always clamoring for her time. Anyway, she got engaged to some asshole. They're still married, last I heard. I think she wanted to stay with him more than carry the show, you know? Like she finally found it, whatever she had been after." He laughed, and we clinked glasses. "But aren't you afraid if you find her after all this, it'll be a disappointment?"

"Of course I am. I'm terrified of that. Or that she's dead. I don't know which would be worse."

"For what it's worth, I'm pretty sure she's not dead."

There was no containing it now. This showman had hooked me. My heart was thudding.

"Do you know where I can find her?"

"I have an idea," he said—and paused to take a sip. "But it's not going to be easy."

"You're telling me. But believe me, I'm committed," I replied, crestfallen he didn't have an exact address, a phone number. My hopes had gotten too high. I was lightheaded.

"Good thing," he said, setting his glass down and pouring a third. Then, "Hey, Les, honey," he shouted toward a closed door, "a guy is here asking for Principessa. Apparently you're still more interesting than the rest of us."

My head pivoted toward the door; my stomach dropped out. And your voice, light, charming, not the voice I'd expected from someone who spent a lifetime breathing fire into the hearts of so many, soared out of the closed bedroom, "Be right out!"