|

|

| Oct/Nov 2017 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Oct/Nov 2017 • Nonfiction |

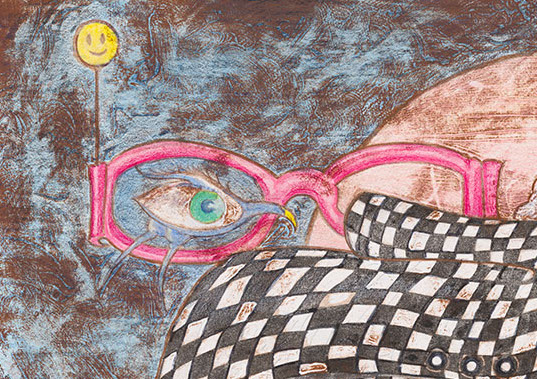

Image excerpted from I Heard It Was a Thorough Examination of the Innocuous by Roe LiBretto

This spring my wife insisted I buy new shoes. To be precise, new slip-on loafers for summer wear so I would look more stylish in my jeans and shorts. I'm used to wearing low-cut canvas Converse—vanilla, army green, gray-blue—and while my wife does not object to these—she even owns a pair of low-top black ones herself—she points out that maybe I want to try another look, something more mature. Something more befitting of a 60-ish man who's gone bald in the back-center of his head. Or to be more charitable to her, something befitting a Professor of Literature and barely famous local author.

We find a couple of pairs to try on while we're out shopping at "the Rack," and all I can see when I put them on is the whiteness of my ankles and foot-tops.

"Don't worry about that," she says. "It's a new look. You'll get used to it."

My wife's tastes are clear and strong—for me. For herself, she shops only the sales racks, and many of her clothes come from her oldest sister whose taste my wife usually adores. My wife is modest about her appearance even though I know she's gorgeous and have been told by several of my friends, male and female, that she is "hot," that I "have nothing to complain about, ever."

It's not that I want to complain here in the Rack either, but I think there is a certain inevitability when a wife takes her husband shopping for shoes. I haven't always been resigned to the women in my life forcing their taste in shoes on me, but there have been enough instances to make me doubt my looks, my tastes. My shoe choice. If shoes "make the man," then what sort of man am I?

We've been married for 33 years, and I remember clearly seeing my wife for the first time. She was sitting with a girlfriend on the steps outside the classroom where our film class would be meeting. She wore a tan beret; her black curly hair, though pinned up, was fighting its constraints. I know she saw me, and I think she smiled, especially with her ebony eyes that pop singer Bob Welch would have understood. I would learn later her smile wasn't exactly full of pleasure in what she saw.

On that first occasion I also noticed her white, zip-up boots. I thought she must be Italian, though I missed that mark by a few countries. When I called roll, I stumbled on her name, Azadeh.

"Just call me Nilly," she said, smiling again.

What she saw in me makes me wince now, though at the time, having just returned from a trip to New York, I considered myself the acme of punk cool. I had shaved the sides of my head—not completely, but above the ears about three inches in a modified Mohawk.

I was trying to be Joe Strummer, lead singer of The Clash.

Complementing my hair was a t-shirt whose sleeves were cut higher up the arm in punk style. The shirt was cobalt blue and on it was a screaming black cat, a parachute, and the legend "NO WAR." I wore scruffy dark jeans, and to top—or bottom—it all off, I wore a pair of black boots that, like the t-shirt, I had bought in New York. The boots were fake leather, made of some sort of flexible plastic. They laced up high and fit snugly about my ankles.

It wasn't love at first punk-Iranian sight, but she did take notice: "When I saw you walk in, I wondered, 'Who is this guy in the Mohawk?' But mainly I noticed your shirt, and I thought that was cool."

I've written about our story elsewhere—how we kept discussing her faulty grammar, our bent toward Marxist politics, our first true date at an Academy Awards party. Mainly we spent our time driving, and before a year had elapsed, we got married. It was only after our service, though, that style became an issue.

Early on as we struggled on two Teaching Assistant salaries, my wife asked that I try a new kind of underwear. Twenty-seven when we married, I didn't consider my classic briefs much. Munsingwear, Fruit of the Loom? What did it matter to me?

"Let me get you another kind," she said, and soon I had several pairs of briefer briefs in multi-colored hues.

I wasn't sure what the material of my new shorts was. It didn't feel like cotton, and it definitely wasn't silk. What are balloons made from? Rubber, or a sort of plastic? That's what I was now wearing.

Even worse, I don't have the kind of torso that lends itself well to European-style underwear. I have neither Italian nor Greek in my background. I don't frequent places like the Riviera, Venice Beach, or even Gulf Shores much. I am of mainly Eastern European extraction, and if you do happen to see a male descendant of Russian Jews wearing bikini briefs, you probably won't be allowed to live. I wore my new briefs to please my wife, though how pleased she truly was once I modeled them, I wasn't sure. She didn't exactly smile.

A year later, when our doctor recommended I start wearing boxers because they allow the coolness and freedom necessary for competent fertility, my wife didn't complain or resist.

My wife likes me in freeing linen shirts, and the color here doesn't matter. With the top two buttons unclasped, she claims this is my "best look."

Before I met my wife, I dated a woman who also loved me in linen shirts, especially white ones. But then, this woman also wanted me to style my hair in what we all recognize now as a Mullet. When I went to my hair stylist and told her, she said, "No way," and proceeded to cut my longish hair so that its natural waves shone through.

"All you have to do to care for it," she said, "is wash and rinse and then shake it out. No more blow-drying."

I loved this look; I looked and felt like ELO's Jeff Lynne, I thought. A "livin' thing."

My girlfriend, however, was pissed.

"You should cut your hair the way I like it. Who else do you want to please?"

I thought about that, and though it wasn't the only factor in our break-up a few weeks later, I was still thinking about her trying to own my hair.

How long has this been goin' on?

Back in the Rack, my wife and I find a pair of medium-brown, fine leather Bjorn loafers that are, I admit, extremely comfortable. They cost about $70, and we agree they're a relative bargain.

"Let's take them home, and you can walk around the house in them," she suggests. "You'll get used to them," and she whips out her American Express. "On me!"

Up until last summer, along with my Converse, the only other summer shoes I had were a pair of Bass sandals. Deep brown, narrow, but closed-toe. My wife bought them for me at Macy's. They were maybe 15 years old, but I had worn them so infrequently that to all appearances, they were new.

But not so stylish.

Before them, I had a pair of flatter, green felt-like sandals, closed-toe, made by Earth Shoes. I looked hippie-ish, I thought, and they were the first pair of sandals I had owned since I was a little kid. To be honest, I always thought boys wearing sandals was a sign of control, of being a "momma's boy."

How on earth could sandals ever be cool?

When my earth sandals finally eroded, I didn't want another pair, but the warmth of the south and my wife's persistence wore me down. She liked the Bass sandals; she thought they made me look like "something," though I no longer remember what that "something" was. Clearly not a punk rocker, and not even a lit professor, I thought, except maybe the sort I saw once cutting his grass in long pleated pants and black lace-up oxfords.

Sometimes I feel weary of trying to look good or the way I see "hip" in my mind. So while I wanted huge black Doc Marten boots, I agreed to wear these sandals. While I didn't feel this way every time I put them on, mainly I hated them and what I thought they said about me: a guy who's given up. A guy whose taste runs to middle age.

I wore them for the last time in the summer of 2016, though I didn't know it would be the last time. True, one of the side straps had loosened. I knew I'd never get it repaired, so I could see the end. What I didn't consider, however, was my daughter, Layla. Her boyfriend, Billy, had recently moved to Wilmington, and we all went to visit him on possibly the hottest weekend of the summer. While I did bring a pair of Converse, I also brought the sandals for eveningwear, thinking of the special seafood restaurant that "the kids" had selected for us. I liked Wilmington, and God knows how we walked its streets that Saturday afternoon and evening. My sandals had finally begun rubbing a blister on my heel, but I persevered because, again, I wanted to look stylish for my family.

The way I thought they wanted me to look.

The weekend passed, and all seemed well. A couple of months later, we were planning a trip to Charlotte to meet up with Layla, Billy, our other daughter Pari and her fiancée Taylor, at an outdoor Dixie Chicks show. Layla called us to check out the hotel arrangements, and as we were finalizing plans, she asked if she could speak privately to her Mom. I'm fine with staying out of these talks, but I couldn't help get concerned when I heard my wife say, "Really? Are you sure? Well... okay, I'll talk to him about it."

Normally I do not suffer from paranoia, which I know can "strike deep"; normally I don't think about such things as intuition, which I know makes me very male. On this occasion, though, both sensations kicked in: "Were you guys talking about me?"

"Yeahhhh. Layla wanted me to tell you something because she was afraid it would hurt your feelings."

Now think about it. Your 22-year-old daughter wants to tell you something but doesn't want to hurt you in the process. What is that something, and what are your options? Unsightly stains or blemishes? Foul odors coming from your body? Your coffee breath?

Or, she's pregnant.

Or she's thinking of converting to a Mega church, or, God no...

She's voting for Trump.

Such thinking is called "spiraling," and before I got down to the bottom (though what could lie underneath Trump... heard it when I said it), I said, "Go ahead, tell me. I can take it," and I braced against our pine dining table.

"Well... it's your sandals. Layla is asking that you not wear them this weekend, or ever again actually. Especially not in her presence."

Still in college, Layla had style sense, and even my wife won't buy anything without her approval. Layla's tastes are expensive, and if she could, she'd take me to Banana Republic and dress me from not the sales rack, but the finer, full-price goods. She has an artist's temperament and flair. In her hands, I know I'd look tasteful, if not a bit business-y, or even preppy. She loves my beard but keeps wanting me to style my hair shorter.

I'm beginning to wonder if she's modeling me after Billy, who could be a GQ model, something my mother has also wanted for me all these years. Long sleeve knit shirts tucked into belted off-white shorts. And loafers.

In so many ways her request about my sandals was a relief. Yet, I had worn them for all those years and no one had ever said a thing about them, which of course meant that no one had ever really complimented them. Truly, do you ever hear these words said to a grown man: "Hey, love your sandals!"

Now I wondered: if my own daughter thought this way, what had others thought or said at all those summer barbecues? At the local bars where we congregated at outdoor tables with our neighbors and friends and all those total strangers? What did I look like walking down summer-lit streets?

So even as I tossed those poor old shoes, I thought back to perceived whispers and snickers of my past—of women laughing and pointing at me, and my feet.

It's easy to forget the shoes of your youth. I know I had Keds, Poll Parrots, Red Goose. I know I wanted PF Fliers but never got a pair. Shoe status among the kids I knew back in the early '60s didn't amount to much, that is until I hit fifth grade and little league baseball and got my first pair of cleats.

My mother bought mine at our downtown Pizitz department store, where I also got my Cub and Boy Scout equipment. Plain black cleats: no frills, definitely no white stripes. They fit well, and when I first put them on at home, I felt dangerous.

Dangerous, that is, until I attended my first team practice where I saw boys of all shapes and older ages sporting 3-striped Adidas, single-striped Pumas, big-tongued Spaldings.

My cleats had no branding at all. They were as unmarked, as unnoticeable, as plain and unworthy as I was a baseball player.

My teammates' flash and competence, on the other hand, befit the cleats they wore. Especially on Eddie Porter, our catcher and coach's son whose enormous feet were encased in a pair of Pumas, and who looked like a pro player to me: his lefty stance, his bat raised level with his eyes, his ability to shoot from home to second in, seemingly, three deer lopes.

The way he spit into the cool red infield dirt.

It could have been the fact that it was my first year and I stunk. Fast balls bowed me; curves—though honestly, no pitcher really needed to resort to such tactics—befuddled me. Since I platooned in the outfield with four other "rookies"—two innings max per awful player—I got at most two bats a game.

In that entire summer, I never once touched a ball with my bat. Not even a foul tip.

I got hit once, and I walked a couple of times. Imagine my joy the following season when, in maybe our fourth or fifth game, I final hit a ball—a popup to short—and behind me in the crowd, I heard my friend Rusty's mother shout to my Mom, "Oh look Jo Ann, he hit it!"

In my first year, if I came to the plate 30 times that summer, I struck out at least 26 of those times. Maybe that stat justified Eddie's impatience with me. Maybe you're thinking had my cleats been Pumas or Adidas, I would have had great success or at least more confidence. There were moments when even I thought that might be true.

In the last game of the year, I did get walked, ending up on third base, where I stood in my cleats watching as our last batter came to the plate and struck out on three pitches.

When you're on third and someone makes the final out, I can assure you no one comes up to you and says, "So close," or "At least you tried." In our dugout, no one said much of anything at all, for the season was over. All-stars would start soon, but my cleats would get shoved back into my bedroom closet, never to be worn again.

The next year I got knock-off Adidas. Three weak stripes, and of course everyone knew mine weren't the real thing. At least I got some hits that year, more likely because the fast pitchers had moved on to Pony League, rather thanbecause of the three stripes on my cleats.

During my last year playing little league ball, I finally got those beloved Pumas. They didn't help, though, as again and again, I struck out. In the last game of the year, I finally made contact again—a groundout to third. I struck out in my second at bat, and our coach, Bobby Robinson, gave me the choice of taking my last at bat or sitting the humiliation out. Our team, the A's, was mired in third place out of a four-team league, so we weren't going anywhere. We were even winning this game, so my last at bat meant absolutely nothing.

Yet I took it anyway. My dad had always told me to seize opportunities even if you don't know their outcome.

"Don't be a quitter," he said.

I was always his good boy.

My friend Frankie Chiarella was pitching for the Tigers. The first two pitches were balls. The third pitch, a chest-level straight down the pike semi-fastball, landed somewhere beyond the left-center field fence.

"Why me," Frankie asked after the game.

And while I could have pointed to my Pumas, I didn't.

I simply grinned.

"God Frankie, I wish I knew."

I also wish I knew why sometimes I react so stubbornly to the advice of others.

Sixth grade, Arlington Elementary School, the night we took the stage in a skit to honor our country's forefathers and mothers. Memory is selective, but try as I might, I remember only two participants from this night.

Mike Folker, a boy I had known since first grade, whose parents ran a Mom/Pop grocery store somewhere down Carolina Avenue. ("Go all the way down Carolina, and then you'll come to a dirt road and you'll see our store.") I begged my mother to take me there, as much to make sure it existed as to buy the coveted Chinese Yo-Yo's everybody but me seemed to have. She finally relented, but three or four blocks down Carolina, she turned around. The neighborhood, she said, looked a little rough.

Recently, on a trip back to Bessemer, I drove as far down Carolina as I could. The road is paved now, but Folker's is long gone.

On stage that special night, Mike played John F. Kennedy, "...asking not what... but what you can..." He wore a dark suit, dark tie, dark lace-up shoes that were tasteful, subtle—a classy style showing Mike and his family knew humility, knew their place. That he was guided by the tastes of others.

The other speaker I remember was a kid wearing Beatles bangs playing Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Me.

I didn't know how prestigious my teacher's choice of me to fill this role was supposed to be. What I did know was I had recently asked my mother to buy me a pair of black and white saddle oxfords, and I insisted on wearing them for my FDR speech. I wanted those shoes because they seemed collegiate according to the images of well-bred frat boys I had seen on popular TV shoes like "The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet." I fantasized about life at the University of Alabama, being in a fraternity, and black and white saddle oxfords, to me, screamed College.

On this night, my shoes complemented my Mod black and white checked Houndstooth pants, an off-white jacket and black tie, and the lens-less wire-framed glasses my teacher thought it appropriate I wear to project that FDR look. I was truly the picture of something, but not something bred of good taste or humility. I was something of my own making—perhaps, I think now, a Presidential Collegiate Beatle.

So I walked on stage to stunned laughter. I think most in the audience would have willingly let slide FDR walking. But highlighting his newfound ability to walk on his own were those blinding black and white shoes. As I tried to explain what we had to fear this night, fears I never knew I had found me.

Our across-the-street neighbor, Margaret Terry, thoroughly enjoyed my performance. Her smiling face and laughter told me so.

"Why did they laugh at me," I asked as we drove home that night.

My parents tried to soothe me by uttering the awful words, "They weren't laughing at you..." and then they added something like, "When people do laugh, that means you're a big hit."

I know my mother tried to stop me from wearing those shoes, but I was too stubborn to listen, so certain that since I loved my shoes and thought they made me look grown up or at least older than an 11-year-old boy, there was no way anyone could doubt me. No way anyone could not appreciate how sharp I looked.

How adult.

Still, I want to scream even now, "Who lets an 11-year-old walk onto a stage in black and white saddle oxfords to portray a stately and disabled world leader?"

And yet, if my parents had forbidden me from wearing my saddle-oxfords, what would I say about them now: that they were too controlling, as they were when they forced me to get a crew-cut in fourth grade, skinning the burgeoning Beatles-look I had been cultivating?

If they had made me conform my image for the skit, would I even remember this event now?

My saddle-oxfords were the first pair of shoes I ever selected for myself. After that night, I never wore them again.

As far as selecting my own garish footwear went, however, I wasn't done.

Any kid growing up in Alabama during the late '60s who was a football fan surely fell under star Crimson Tide quarterback Joe Namath's spell. Though none of us could direct the deep downfield spirals Joe Willie could, there was one thing we could do to pay homage to our hero and to pretend that one day we might be him.

Once Joe became a New York Jet, he taped his black cleats almost wholly white, and when the American Football League didn't stop him there, he adopted solid white cleats. Soon, his teammates Don Maynard and Bake Turner followed suit, and before you knew it, the league was saturated in white shoes.

Just like the guys in my 8th grade class.

We adopted white lace-ups, white loafers, and best of all, white side-buckles. Mine were slip-ons with a high tongue and a gold buckle on the side. My mother and grandmother bought them especially for me, and their other outstanding feature was the slickest sole on any shoe ever.

So slick, I busted my ass running to a jukebox at a Pasquale's Pizza Parlor in Tuscaloosa.

We'd wear them without socks, with jeans and flared-leg, mod trousers. We'd wear them with shorts. We'd wear them anywhere, at anytime, and yes, even to church.

It's useless to ask who we thought we were, what we thought we looked like. Some of us still sported crew cuts or flat tops. A few dared Beatles bangs. Most of us wore window-pane checked pants, and some went as far as to accompany their shoes with wide designer white belts and equally wide white watch bands.

Questioning such a look didn't occur to me until the following summer when our family won a vacation to West Palm Beach, Florida, sponsored by Long-Lewis Ford, a car lot out on the Bessemer Super Highway. Four long days and three nights for free, and we added two more nights in Ft. Lauderdale after. We needed to because we spent one whole day in West Palm Beach listening to an obligatory land deal, the cost of our "free trip."

"So they want us to show up at the office tomorrow," my Dad said, after we checked in that first night. "Just a couple of hours to listen to their proposal."

And maybe it was just a couple of hours, though when you're 14 and want to be on the beach because you just know that the girl of your dreams is waiting for you, two hours, two years, what's the difference? At least I got to wear my white shoes out to supper, thinking that since I missed the beach that afternoon, that same girl would be waiting for me over crab and lobster.

Except at the mad deal that afternoon, my white shoes had been compromised.

By Joe Gracie.

Joe Gracie was our land-tour guide, and he drove us around a corralled lot, a "typical one-acre lot," he told us. A sandy, weedy, otherwise barren area, which, indeed, had a sign over its front entrance:

"One acre lot."

Typical.

My brother remembers that Joe Gracie had a thin comb-over, wore a gold ID bracelet, a gold chain, and a gold plate that, my brother says, stated either "Joe" or "Gracie" or in our dreams now, maybe even "Joe Gracie."

What I remember, though, were Joe's powder blue double-knit pants, his matching, patterned blue shirt. His white patent-leather, buckled shoes, and his proudly displayed white belt.

A late middle-aged man trying not to look square and achieving the blatantly opposite result. I know he was trying to keep up, trying to look his best, but in the end he achieved only two things: he achieved failure in selling us that barren plot of land, and he cured me of my white-shoe mania. After we returned to Bessemer, I stashed my white shoes in the back of my closet where, the next spring in her annual rite of purifying our house, Mom found them and chucked them into the garbage.

That fall I dragged my mother to the Village Bootery in Midfield's Western Hills Mall and cajoled her into replacing my slick white shoes with a pair of ankle-high boots. They had three-inch wooden heels and were covered in a reddish suede except in the front, where a multi-colored set of stripes—black, brown, gold—took over.

This was my David Bowie Glam phase.

The boots cost $75, and the following summer of 1973, they accompanied me back to West Palm Beach—we won another trip before we left the previous summer—and I wore them proudly on those humid summer evenings at the Red Lobster and other assorted family eateries.

I kept my boots through my sophomore year in college, and I remember wearing them on the night I was elected editor of our campus newspaper, and on the night I went clubbing with my academic advisor, Tom. I loved the attention back then, though on that clubbing night, I got "land proposals" I really didn't want.

When I was four years old, I remember my grandmother waking us up in the middle of the night, yelling, "Jo Ann, Jo Ann, the house is on fire."

Details stand out for reasons we may never understand, but on that January night as my father grabbed my infant brother and my mother grabbed me, the detail that stabs me more than any other is that my mother made the conscious decision to snatch my Sunday shoes from the closet near my bed and put them on me, though she put them on the wrong foot.

Those shoes were two-toned lace-ups: a black base and sole with a solid white top. I remember her forcing them on my wrong feet, but there they stayed until we found refuge at our across-the-street neighbor's house.

Margaret Terry's house.

Before the night of our house fire, no particular shoe stands out in my memory.

This past week I participated in our downtown bookstore's "Page Pairing" event, where an author's book is matched with a certain wine. Customers sample various vintages and choose a book at the end. My essay collection, Don't Date Baptists and Other Warnings from My Alabama Mother, was paired with Bel Star Prosecco, a suitable choice in that we are both dry and white, with a bit of fizz.

Two of the patrons, a young woman and her formerly-Catholic husband, discussed with me the logic or illogic of anti-denominationalism, not that I really understood all the nuances. Actually, most of the wrinkes in Protestantism confuse me. But at least now I think I understand shoes.

Reaching the reality of Mega-churches, this young woman looked at my boots and stopped the non-denominational madness:

"I love your Fryes!"

This couple had eyed my book earlier in the evening, and only the wine in their hands assured me they might not be offended by my book's title. They were just so stony-faced. I don't automatically fear or mistrust Baptists, but this is the South.

Yet, they bought my book, which restores my faith in something. Maybe my instincts, for as proud as I am about the book, I love my Fryes, too, especially since I bought them from the Rack online, half-price, without trying them on or asking anyone's advice. They are pretty cool: ankle-high, reddish-brown-already-scuffed leather, zip-up back, with that iconic Frye buckle on the sides.

I think they are the shoes I always wanted—the ones that make me feel so cool, so bad-ass even now that I'm a man in his early sixties. Shoes for a man who hasn't given up.

Shoes that are the antidote to sandals.

After the event, at which I also wore skinny-ish Levis and an open-neck blue linen shirt (tail out), my wife suggested I looked "mighty juicy," our favorite infamous Robert Mitchum line (Cape Fear).

This was the night before our 33rd anniversary, and as we left the bookstore, my wife looked over at me.

Her eyes, I noticed, were shining.