|

|

| Oct/Nov 2016 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Oct/Nov 2016 • Nonfiction |

Long ago in 1793, Jean-Pierre Blanchard first ascended in American air while George Washington looked on. In the next century there was notable ballooning during the Civil War, by the Union Army Balloon Corps. Like most Americans, though, my own family have never been balloonists, except for a memorable flight three of us took over Rome in 1983, cruising slowly over the ancient Forum and Capitol in a Goodyear blimp. My family waited on the invention of powered flight to get off the ground. Even so, it was a quarter-century after Orville Wright's first flight in 1903 that a Bridges first took to the air. My father was that family pioneer, in the late 1920s.

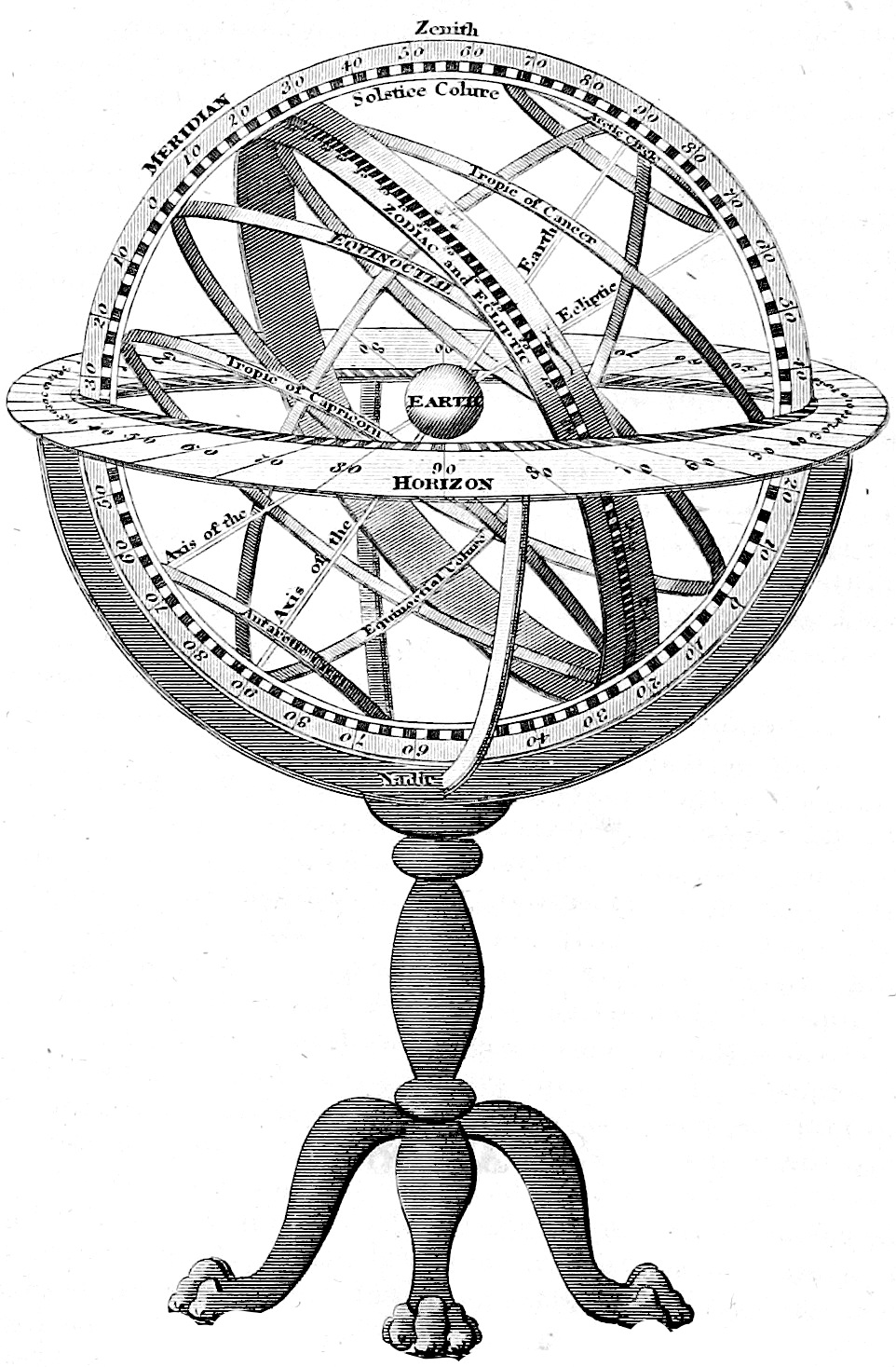

He first flew on a Sunday morning over the Isthmus of Panama. I remember well his account of it, that I heard more than once when I was a small boy on the South Side of Chicago. My parents would sometimes on a Sunday have several friends to midday dinner, in the modest house they had finally been able to buy in 1938, when my father, whom we called Gov, returned at the age of 35 from a long business trip to Europe and Africa. The previous Christmas, when I was five, my parents had given me a geographic globe a foot in diameter. Gov set me to learning where all the countries were shown on that little world's surface. Soon I could find almost all of them, although I never mastered the locations of all the British colonies in Africa (the large part in red) or the French ones (also large, and green). Even today, when all are independent and varicolored on the map, I need a minute or so to find Sierra Leone or Togo.

When our guests came, Gov would offer them an Old Fashioned. The men talked in the living room while Mother labored in the kitchen in the company of the other ladies. My father would invite me to bring my globe out of the bedroom as the men sipped their drinks. Gov would say Peru or Norway or New Zealand, and I would point to it. I was happy to get compliments, but my real prize was the maraschino cherry at the bottom of Gov's glass when he finished his first of usually two drinks. I think I was shameless enough to beg cherries from the guests, too. The fruit was sweet, and no doubt I got a drop or two of whisky along with it. Fortunately I never became addicted to Bourbon; I have admittedly drunk a lot of other stuff.

So it was that I stood by Gov and heard all he had to tell guests. He liked to tell stories, and he was funny. Sometimes they were tall stories about his family's life on their Tidewater farm when he was a boy. Hard times, they were. Food was so scarce, his development was slow; he did not learn to talk until five, and at 12 he had weighed only 47 pounds. Toilet paper was an expensive luxury, but pine cones were plentiful...

But he also liked to tell what I think were true stories about his truly extensive travels, including his first flight. He found himself one Saturday evening in Colón, on Panama's Caribbean coast. Prohibition was the law then in the United States, but not in the Republic of Panama, and over drinks Gov met a young US Navy pilot who was stationed nearby at the Coco Solo base in the Canal Zone. (The gringos are gone, long since; Coco Solo is now Latin America's largest container port.) Gov admitted to the pilot that although he had traveled up and down Latin America, he had never been in the air. "Come on over to Coco Solo in the morning," said his new acquaintance, "and I'll take you for a ride."

In the morning Gov went to Coco Solo with a serious hangover from the previous evening and found the pilot, who at a guess may have realized once sober that he would violate regulations in giving a ride to a civilian. No matter; they took off. The craft was a biplane of some sort—these were years when the Navy was trying out a number of aircraft types—and it was not very fast, but the pilot did loops and dives for the benefit of his passenger who got, he said years later, quite ill. That did not deter him from taking, before long, Pan American's first flying boats along the Caribbean coast. I have his old red passport showing a 1930 arrival by air at Brownsville, Texas, where the twin-engined Consolidated Commodores ended their run with at most a dozen passengers.

Gov traveled a lot, at home and abroad. His domestic trips were mainly between Chicago and New York by train, but when he went on business to the West Coast in the late 1930s, he would take a Douglas Sleeper Transport or DST, a version of the Douglas DC-3 with seats that converted to 14 berths for overnight flight. By 1937 the DSTs of Trans-World Airlines were flying from Chicago to Los Angeles in 13 hours, with stops en route at Kansas City and Albuquerque. The overall speed was almost 130 MPH!

In an earlier essay in Eclectica about my family on the waters, I told of my father's 1938 trip by flying boat across Africa from Mombasa to Alexandria, and onward to Brindisi, Genoa, and Southampton. Then, in 1939, well recovered from the dysentery and typhoid that had almost killed him in Africa, Gov flew on Pan Am's huge new China Clipper across the Pacific to Manila, with overnight stops at Honolulu, Wake, Midway, and Guam. Gov went on from Manila to Singapore, Batavia (now Jakarta), and Sydney. He was scheduled to take another huge flying boat, a four-engined Empire of Imperial Airways, westward from Australia to England. After he reached Sydney, Hitler's invasion of Poland and the onset of World War II closed down Imperial's long route (ten days of flying, with nine overnight stops) from Sydney to Southampton. Gov retreated to America by ship, and a month later sailed from New York to Southampton, no doubt thinking how he had originally planned to descend there from the skies.

My own first flight was, like my father's over Panama, uncomfortable. In November 1950 I was a sophomore at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Gov telephoned me from Chicago to say he was going to New York on business on short notice, and he hoped I would fly down and meet him. He would pay for the ticket, since he knew I was not long on money. (He paid my tuition, room, and board, but for other expenses I was mainly dependent on my savings from a summer job delivering groceries.)

I took the Northeast Airlines afternoon flight from nearby Lebanon down to LaGuardia. The plane was a Douglas DC-3, one of hundreds of the sturdy, twin-engined propeller planes that had first gone into commercial service in 1936. The DC-3 was not large. As I have written, the sleeper version had 14 berths, while the one I took from Lebanon had just 21 seats. That afternoon we flew down the Connecticut River under a stormy sky at an altitude of no more than 1,000 feet. It was a rough ride that took an hour and a half to reach La Guardia in New York. I did not vomit on the way, but I wanted to.

Nor was dinner with Gov entirely happy. War had begun in Korea in June, and Dartmouth's 3,000 undergraduates, all of us young men, expected soon to be drafted and sent off as infantrymen to unknown Asia. There was no use in studying—or so I felt—and I conveyed this to my father. It was a bad case of sophomore slump. Gov had known hard times in his life but had done no soldiering; he had been too young for the first World War and too old to be drafted for the second. In any case he wanted me to persevere in my studies for as long as I remained a student. I saw little good in doing that if I was soon to be in the trenches.

I went back to Hanover on the overnight train, and soon the government decided college students could be exempted from the draft. I felt aimless. I had not wanted to go into the Army, but I had expected to do so. I was an English major, but my vague idea of teaching English in some pleasant New England college no longer made sense. I survived, if barely, my sophomore year and discovered a field more fascinating than old English elegies: Russian literature. I immersed myself in the culture and language of that cold, exotic place and completed four years at Dartmouth with a much improved academic record. As a sophomore I had almost been suspended for poor grades; my senior year I was a proud Rufus Choate scholar, ranked in the top five percent of my class.

Four years later, in my mid-20s, I came back from service as an Army private in France together with my wife and our son David, aged three and a half months. If I had had no family, I would have gone home on a transport ship as I had come. On our westward journey the Army kindly—the Army was known for its kindness and wise management—let us fly. We took off from Orly airport in Paris late on a July evening on a Lockheed Constellation. The Constellations were four-engined, propeller-driven planes, long and sleek. They were big and fast for their time; they cruised at 340 MPH and could accommodate up to a hundred passengers, but they could not cross the Atlantic with a full load, especially flying westbound into the jet stream.

We landed at Shannon in Ireland at two in the morning, and all got off the plane while it was refueled. David, who had been sleeping while in the air, began to cry, and we bought him his first-ever ice cream. He liked it, and he has not lost his taste for it since then.

We were bound for New York, but had to make yet another refueling stop at Gander in Newfoundland. Today Gander has a large, modern terminal, but in 1957 there was only a small wooden building. Not many years later, a Czech acquaintance told me his Gander story.

His story dated to the early 1960s, when he had just graduated from Charles University in then-Communist Prague. He was determined to make his way to the West. To do so he would have to get on some student tour that went abroad. Alas, the tours all went to the USSR or elsewhere in Communist Europe, but then he found one that was going to Castro's Cuba. He signed up, hoping somewhere en route to Havana there would be a stop where he could run away from his group's official minders.

The plane stopped at Shannon to refuel. Crew and passengers all went into the lounge. He walked up to the co-pilot and said, "Next stop, Havana, right?"

"No. Too much head wind. We'll have to refuel at Gander, too."

That was what he hoped to hear. Better to end up in North America than in Western Europe.

In a few hours more they landed at Gander. All deplaned and began walking to the little transit building. It was my friend's last chance for freedom. He broke away from the group and ran into the Canadian woods, fast and far. A decade later he was a successful entrepreneur in Ohio.

Some air trips have gotten me closer to heaven than I have ever been on the mountains. Some trips admittedly were humdrum. I have only crashed once, in Colombia, and did so rather softly. That was in my younger and less responsible years.

We were living in Panama, and I wanted to see all I could of the country and its people and its problems. I traveled in a slim piragua up the Bayano River into the country of the Cunas, and I went by air several weekends to visit the Cuna people on the San Blas Islands, just off Panama's Caribbean coast. There was no road to San Blas. I found a pilot named Manuel who had a shiny red, single-engine Stinson. Several times he flew me across the Isthmus, from Panama City to one of the grassy strips on the Caribbean coast that the United States had built in World War II, when 100,000 US soldiers occupied much of the Isthmus of Panama in order to protect the Canal.

After several trips by Stinson to San Blas, I met one evening at dinner an American pilot who worked for an air charter company—Panamanian friends said it belonged to CIA—that flew around Panama and Central America. I told the pilot, a tall Russian-American, about my flights to San Blas. "My God," he said, "that plane's a death trap! Manuel painted it bright red, but underneath it's all rust and corrosion." I found a different craft for my next San Blas trip.

My crash in Colombia came about as the result of my friendship with Tomás Guardia, Jr., who was Panama's top civil engineer. "Tommy" Guardia, then in his late 30s, headed the committee planning how to close the 500-mile gap in the Pan-American Highway, which was to stretch from Texas to Argentina and had been under construction for years. This so-called Darién Gap stretched from Chepo, 30 miles beyond Panama City, through the forests of Darién into Colombia. Guardia had made his way across this Gap several years earlier, mainly on foot, with great difficulty. Building the road would not be easy.

Tommy called me one day to ask if I would like to fly down to Colombia the next day. He was to meet with his Colombian counterparts in a village near Colombia's Pacific coast, to discuss the planned route across the Gap.

"The only plane I could find to charter," he said, "is an old DC-3, and it has plenty of seats. Would you like to go? We're going tomorrow, and we'll be back in Panama late tomorrow evening."

The Darién Gap was not on my list of matters to be investigated—I was a political and not an economic officer—but I said to myself Nil humanum mihi alienum est, and my boss said to me, okay. Next morning I promised my wife I'd be home that evening in time to help her get ready before four Panamanian friends, a lawyer and a politician and their spouses, came to dinner. I kissed her and the children goodbye and soon was airborne in the old but sturdy (far sturdier than that red Stinson) DC-3.

We passengers were only four: me, my friend Tommy, his father, Tomás Guardia Sr., who had been the first head of the Republic's highway department, and another highway engineer. There was a pilot and a co-pilot and a pretty aeromoza (which, like "stewardess," may no longer be a politically correct term, but I am writing ancient history), and she served us Cokes. The day was fine and the ride smooth. In two hours we reached our destination, a dirt landing strip outside a coastal village west of Medellín. We flew over the strip, and I saw at one end a little twin-engine Beechcraft the Colombian engineers had flown down from Bogotá. The strip looked smooth; a bulldozer had gone over it and left a mound of dirt stretching across the end of the strip.

The pilot had mentioned earlier that this was his first flight to this less-than-major airport. He flew down to make a low pass and take a look before landing. He flew too low, and there was a bump. A wheel, or perhaps both wheels, had struck, lightly, the mound of earth. We flew up and around again. We should have flown back to Panama where there were fire engines and ambulances, but we came down again and landed. I was looking out the right-hand window. The wing was lowering toward the ground; the wheel must be collapsing. If it collapses any further, I thought, the propeller blades will hit the ground.

The next moment the blades hit the ground and bent, and the wing crumpled.

We stopped in not many yards. The aeromoza opened the door at the rear, and in a minute deployed the airstair and yelled (was it in English or Castilian?) "Get out!" We got out and ran some distance away from the plane. But the pilot had cut the ignition, and there was no fire.

We were standing in hot sun at the edge of a muddy village in Colombia. All I could think was that 300 miles north, not long from now, friends were coming to dinner. I doubted my wife would find a slight crash a sufficient reason for me to absent myself.

The Colombians quickly told Guardia that their pilot would take his old father and the cabin attendant back to Panama... and there was room for one more.

"Peter," said Tommy, "You go. Otherwise you may be here a long time."

I went and got home in good time for dinner. As I expected, my wife was not impressed by my little adventure.

After two years in Panama, the five Bridges left the Isthmus for a short vacation in the US and a transfer to Europe. The first leg of our journey was from Panama City to Miami on a new DC-8 of Pan American Airways. It was my first flight on a jet aircraft. Pan Am had put the four-engined DC-8 into service just months before. Soon we were at 30,000 feet, and the sun rose in clear sky. We flew over Castro's Cuba, so high that the big island below us looked like something on a huge map. It was exhilarating.

We flew the now-defunct Pan Am often. Foreign Service officers were required to use US carriers. Our last Pan Am flight came in June 1974, when we flew to New York from Prague, on transfer to Washington after our three years in Czechoslovakia. Pan Am had a weekly non-stop flight from Prague to JFK, and that was the flight for us—a lot of us. Besides Mary Jane and me and our now four children, we had agreed to escort to New York the three children of another embassy couple, the Hoovers, who were going to spend the summer with grandparents in the US.

We also had a dog named Dingo. This was a bright and loving, black-haired mutt of mainly sheep-dog origins. He was our constant companion on our hikes and climbs in Czech meadows and mountains. He weighed around 45 pounds. The weight was important. Joe Basso, Pan Am's Prague airport manager and a good friend, told me that regulations permitted passengers to carry into the plane's cabin a dog in a carrier, if dog and carrier together weighed not more than ten kilos, i.e., 22 pounds.

"Joe," I said, "I think Dingo weighs a little more than the limit. What can be done? We really want to have him in the cabin."

"Well," he said, "If you can just carry him on the plane in some sort of case, I'll allow it."

We had a fair-sized wicker suitcase that air could penetrate. I had used it once to carry a long-departed family cat onto the SS United States. Dingo was much heavier than the cat. We tried putting him in the case. He resisted, strongly, but at least we could see that he would fit if...

Dingo loved paté above all other things edible. Mary Jane bought him a supply of paté, as well as some sleeping pills from the local Prague vet. The dog was fast asleep when we reached the airport. I lugged him in his case to the check-in counter. Joe Basso was there.

"Just put the case on the scale," he said to the Czech check-in clerk, and then he asked her, "How much does it weigh?"

"Exactly ten kilos," she said.

The nine Americans walked out to the plane, one of them a little slowly since he was carrying a wicker case certified to weigh ten kilos that somehow felt like more than twice that, 50 pounds. The plane was single-class, and they gave us the nine seats farthest forward. After some time over Europe, I opened the case to see if all was well. The dog thrust his head out, and with all my strength I could not get him back in the case. There was a thin metal stanchion stretching along the floor under my footrest. I let Dingo exit the case and clipped his short leash to the convenient stanchion. A couple of hours later, a middle-aged passenger came strolling up the aisle to stretch her legs.

"Oh," she said, "A big dog!"

"Not so big," I said, "Just ten kilos."

That afternoon the jet stream was weak, and we flew far north on our way west. We were flying over the great gleaming Greenland icecap when Dingo woke up. Mary Jane offered him more paté with pill, and he slept until New York. That was our one and only flight of nine plus dog.

I have had many humdrum flights in airplanes, but the several trips I have taken by helicopter have all been interesting. My first was a flight in a Marine craft over the Somali coast, when I was serving as ambassador at Mogadishu. With the agreement of the Somali government, our oceanographic vessel USNS Harkness was doing a hydrographic survey of the waters off Somalia's 2,000-mile-long coast. The Harkness, a 5,400 ton vessel with a cruising speed of only a dozen knots, had a civilian crew and a Navy oceanographic unit, helicopter, and crew. There was something I wanted to see, in a roadless region 500 miles up the Indian Ocean coast from Mogadishu, and the commander of the Harkness, Capt. Garrett Wanzor, kindly said I could sail with them. I took along my friend Martin Florin, the German ambassador.

What I wanted to see was Ras Hafun, the easternmost point in Africa. A large tableland with cliffs 500 feet high juts out into the ocean, and behind it on the landward side are broad lagoons. There, a firm from Milan built a salt works that by 1929 was exporting 300,000 tons of salt a year. The works had been bombed by the British in World War II, but in the 1980s American and German studies had suggested the possibility of rebuilding it.

Four days' sail from Mogadishu brought us on the Harkness to Ras Hafun. The helicopter pilot welcomed Florin and me on board his craft. We buckled ourselves in, on seats along the right wall, facing the cargo door on the left side that was left open to afford us a good view. When we were over the vast evaporating pans and the long aerial cableway that carried the salt out to waiting ships, the pilot kindly heeled over to the left, so that we could look not only out but down, a long way down. It was a little disconcerting at first, but we had a good look. It would take many millions to rebuild the works, but the world salt market was good, and a rebuilt works could be important for the economy of the eighth poorest country in the world. In the event, nothing was done. A quarter-century later, that coast became a line of bases for Somali pirates who hijacked many merchant ships, as we saw in the 2013 film Captain Phillips.

My second helicopter flight was over less exotic territory, to Manhattan from La Guardia, flying straight toward the great wall of skyscrapers until we dropped and landed, just right, on the East River's edges. No one had told me it was such a dramatic way to approach the city. It was an even better way to get to Gotham than crawling over a crowded bridge in a taxi, or rolling through the dark old rail tunnel under the Hudson River to Penn Station.

Another time, in 1977, when I was heading the executive secretariat of the U.S. Treasury during the Carter administration, I was helicoptered one morning from the Pentagon out into the Appalachians, to see the secret site in a mountainside where top Executive Branch officials would take shelter from a nuclear attack. Treasury was allocated space for 15 or 20 key officials, including me.

But, I thought, while we 20 stayed safe under hundreds of feet of rock, our spouses and children would be sheltering as best they could in home basements. The colonel who was briefing us did not touch on that. Well, I did not think we would come to nuclear war. If it did, I thought, my first duty would be to head for my family.

Later, when I had left government and worked for Shell Oil Company in Houston, three Shell colleagues and I spent a day flying around Mongolia with four of our Mongolian counterparts in a huge Soviet-made helicopter. This was a slightly rusty Mi-24 that had seats for eight passengers and a crew of four, including a pleasant cabin attendant who served us tea.

We flew southeast from Ulaanbaatar to a land of grassy steppes and long views toward distant buttes. We landed near a big ger, a yurt, and the people came to greet us. It was spring, the grass was good and green, and small herds of cattle and horses were grazing near and far. The scene reminded me of my days working on a drilling rig in Montana. Here there was no rig, at least for now, but there were a few shows of crude oil rising to the surface of the grassland.

The Mongols were anxious for us to sign an exploration contract and kindly put us up in the grand villa, several miles from Ulaanbaatar, of Mongolia's last Communist dictator, Tsedenbal. The next day at dawn Don Frederick, our head of exploration, and I ran out from the villa, on a path up through woods to a grassy mountain ridge. We saw along our way a number of big red deer.

Our second day, when we reached the ascending ridge, we saw, 100 yards up the ridge from us, a gray wolf. The two humans and Canis lupus chanco looked at each other for a minute, and then the animal ambled down into the trees. A couple of hours later we met with our Mongolian hosts. Don Frederick told them of our encounter. "Ah," said the Mongolian company chairman, "The wolf means good luck. We shall surely sign a contract!"

But we did not. My judgment on Mongolia's political and economic future was positive, but the geophysicists decided it would not be a profitable project. I have never gotten back to that hospitable country. I came away from Ulaanbaatar with a pretty cashmere sweater for my wife, a bottle of good Mongolian vodka, and damaged hearing. The noise level in the old Soviet-built helicopter had been far over a hundred decibels. We had brought no earplugs from Houston, not anticipating our flight in the Mi-24. I recall now, as I finger the little devices atop my ears, that for several hours after the flight I was totally deaf.

My colleagues and I had flown from Houston to Beijing, and the next day onward to Ulaanbaatar. I had hoped we might take the train—as I have written earlier, I like trains—from Beijing into Mongolia, to see the countryside, including the refinery the Soviets had built along the rail line at Zuunbayan that had closed down in 1969 after a fire. Alas, the train was running only three days a week, which did not fit our schedule, so we flew to Ulaanbaatar in a twin-engine, Soviet-built An-26 that landed on a dirt runway outside the national capital.

On our helicopter trip I asked our Mongol hosts if we might fly over the ex-refinery and the oil field, also built by the Soviets, that the refinery had drawn on. We did so. The field, with old derricks still in place, was an environmental disaster. A broad river of black congealed oil led from the derricks far into the otherwise unspoiled grassy steppe. The Russian operators must have seen Gone with the Wind: "Frankly, comrades, we don't give a damn!"

From Mongolia I flew west on what was my first, and only, trip around the world. The Ulaanbaatar to Moscow stretch was on a Soviet-built, three-engine Tu-154, perhaps the fastest civil aircraft in the world, with a cruising speed of over 600 MPH. We flew high over the lakes, mountains, and forests of northern Mongolia, which I had hoped to see on a return trip—had we signed a contract.

That was my last of many flights on a Soviet-made plane. Perhaps the most memorable had come in the spring of 1963, when I was an officer of our embassy at Moscow. One evening I was at dinner with my Australian embassy friend Bill Morrison, who was later to abandon diplomacy for politics and become his country's defense minister. Comparing notes, we found that no one from either embassy had visited Siberia for a long time. There might be little the authorities would let us see there, but it was better than sitting in Moscow and reading the lies in Pravda and Izvestiya.

Morrison and I flew overnight, nonstop, from Moscow to Khabarovsk, 4,000 miles, in a huge Tu-114. This was a transport plane developed from a strategic bomber that NATO called the Bear. It had four colossal turboprop engines and could reach 575 MPH, faster than many jets. And it shivered and shook, all night, as we flew east.

In Khabarovsk the hotel management kicked a Soviet citizen out of his room and gave it to us. That evening we invited him to come by for some of the Scotch whiskey we had brought with us for emergencies. The next evening, he insisted on reciprocating our hospitality, inviting us to the small room in which he had been installed. He had two bottles of Armenian cognac and a cucumber to offer. He said, "We Russians believe one should never drink without having something to eat." We ate the cucumber and drank the cognac.

At some point our host revealed he was an Aeroflot navigator. We told him we had arrived by Tu-114. "My God," he said. "We never fly one of those if we can help it. Three have crashed."

Years later, I read in Nikita Khrushchev's memoirs that he had initially balked when he was told his trip from Moscow to New York in 1959 was to be on a Tu-114. "At times," he recalled, "certain mechanical failures had occurred, which caused us concern..." Finally he agreed to take the Tu-114, after Andrei Tupolev, the designer, said he would send his son along "in case of need."

Khrushchev landed safely in New York, and so did we in Khabarovsk, but I never forgot what the Aeroflot navigator told us (which I reported to Washington, after we had returned to Moscow on other types of planes).

I had a different experience after I arrived in Moscow from our Mongolia trip. It was a Friday evening in the late spring of 1991, and I spent the night in the old Intourist Hotel, a 1970 eyesore near the Kremlin that was later razed. At dawn on Saturday morning, I went running down side streets. Not a human was in sight. After a mile I saw I was being followed by a pack of four dogs. That would not have happened in the recently-ended Soviet police state. Well, I was not harkening for a return to those terrible times when not just stray dogs but so many humans were shot. I turned onto a main street, Mokhovaya, and the dogs disappeared.

That afternoon Aeroflot brought me happily to Rome and to my wife. The next day, Sunday, we climbed a small peak in the Apennines with a half-dozen Italian friends who had been our comrades on many mountains in past years. At midday on the grassy summit, we stopped for our usual picnic. We unloaded from our backpacks good Italian things to eat and drink; the Bridges share was more exotic, including a loaf of delicious dark bread from a Moscow bakery and my bottle of Mongolian vodka.

A day later I completed my circumnavigation, landing in Houston, that most interesting and prosperous city that was already nearing torrid summer. I never found a way to live in the cool green Apennines. Sometimes I wished I had. Meanwhile, although I confess to liking trains above all other modes of travel, I have continued to fly, to places like Reykjavik and Rome, Bergen and Edinburgh and Salzburg, Istanbul and Tbilisi—and to Gunnison in Colorado's high country, which is cooler and higher than the Apennines and still better supplied with wildflowers, bears, and friends.

Speaking of the West, our son-in-law Drew Caughlin is the family's aviator today. Drew is a skilled pilot whom I have flown with more than once. In the long months of Western forest fires, he flies long hours in a twin-engine turboprop Commander with a single passenger, a Forest Service supervisor. This is the "air attack." They cruise high above the great fires, the air attack directing the fire suppression efforts below them of tankers and helicopters. Ten million acres of America burned last year, and our warming climate ensures much more work for Drew and his dedicated comrades. Seeing some of Drew's dramatic photos from the air, I tell myself that after a long life with occasional small adventures, vicarious adventures can also be fun.