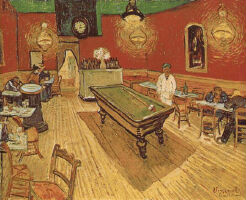

The Night Cafe by Vincent Van Gogh

Boy meets girl. They are parted by some outside force. Somehow, they overcome whatever and end up together again, in life or in death. Or, as certain reference texts might define the romance, person engages with person, things happen, and ultimately, said people understand their love is nothing if not unfailingly enduring. Angie would add to that the condition that masculine-inclined person (m) symbolically or physically takes feminine-inclined person (f) sexually by force, (f) resists momentarily, (f) falls in love with (m), (f) pines for (m) in silence, waiting until the moment (m) clears the way for more permanent, if fatally flawed, arrangements.

Angie's blind Aunt Bernetta and Bernetta's illiterate friend Mirabelle, to whom she reads, react favorably to the formula. The same inspires rebellion in Angie. From what juncture of this structure might she depart, she couldn't imagine.

The scene opens on Angie, punching away at a portable computer, an open can of pears in light syrup at her side. This is a true love story, she writes. (m) is in the corner, refusing to smoke. His male companion is put off, leaves. (f) sits at the bar just yards away. She is not fitting. She is dressed like a Third World secretary in a baby blue suit with a white ruffled collar. (m) gestures. Angie spears a slice of pear.

Parlez-vous français? another man asks.

No, (f) says.

So English, then? he says.

Sorry, she says. I'm really busy.

Angie highlights the text and deletes it. She tried for three years to learn French and she can't speak a dozen words of it—one of her many inadequacies she regrets.

She puts her portable to sleep and locks it in her suitcase, which she has locked to a table leg in the dining area of the hostel.

She has come prepared, she always does, with a swimming suit. Today she wears it under her clothes. Outside she doesn't have benefit of a flashlight as she is not accustomed to needing one. The hot tub is empty and in fact the light is not on. In darkness she takes off her T-shirt and skirt and sneakers and finds a dry place to lay them. The tub is half-uncovered. The scarcely chlorinated water is not very hot. There are no bubbles.

A man is supposed to be supple, she thinks, or at least not thin. (m) will not be thin. Will he see her naked? Mirabelle would insist. For (f), the vagina is her eye to the world or the world's eye to her. It is at times black, at times red.

Angie feels around outside her new one-piece Speedo, which she bought for almost a week of tips and loves. What kind of eye is always covered? What kind can see underwater? I'm no fish, she thinks.

She is romanticizing, she knows.

When she arrived in Moab yesterday, she gassed up then stopped for ice cream. She thought to herself, Environmentalist, yuppie—is there a difference? In her heart she knew there was, and she sensed a couple of shots of tequila would make the difference clear, but in this bike-ridden, tourist-shop town, she couldn't tell one from another. They all seemed to have something in common: they carried cash.

She thought she might go camping. The road straight west of Moab was dusty and crowded. Some campers had pitched tents on cliffsides. One strong wind and the tent and the people and their gear would blow over. The survivors would have regrets. In the end she became anxious and drove back to Moab.

For (f), the vagina is her access to the world, or the world's access to her. Sometimes it is shut, sometimes open.

It will not do to bring in sex, she thinks. The actors would be lost.

(m) meets (f) at a convenience store in Green River, north of Moab. Their hiking boots match, and she tells him this. Also, they are each buying a king-sized pack of M&Ms and a plastic bottle of pop. He Coke, she Mountain Dew. They walk to their cars together. Turns out, they both have Idaho plates; she 8B, he 4B. Neither have passengers.

Where are you going? (m) asks (f). To Moab to rent a truck, she says. From there I'm going south to Beef Basin.

Would you like to go with me? she says. We'll see when we get to Moab, (m) says. I'll follow you.

But Angie didn't take a notepad into the hot tub. Later she writes: The lovers meet in Green River. (f) has a broad chin and a long neck; no does (m). (f) has big ears; (m) has ears so small, (f) must look for them. (m) sees the flesh of her stomach drapes over the rim of her shorts as fine fabric might. (f) notices his knees are rough with wear, suggesting the hard, determined work of a man who labors. A man, maybe, who loves. They decide to rent a truck together then, on the advice of Alamo Rental, they head straight to Beef Basin. They set up camp.

You can't get straight to Beef Basin from Green River, a young woman in a parody cowboy hat says.

Jesus! Angie says. Are you reading over my shoulder? It's not right—

You were reading it outloud, knucklehead. And I'm just trying to help. You have to go through Moab to get to Beef Basin.

Oh. Okay. Sorry. Angie snaps her laptop shut and runs upstairs to her bunkbed.

In the second scene Angie is driving a Cavalier on the paved road to Newspaper Rock. A twenty-year-old blond with a cleft chin sits beside her. He is a regular at the hostel, he said earlier, an American. Canyonlands is old news to him. He could show her some awesome trails, he said. They talked of white alligators (brothers, all), of picking cherries and apricots, of silver versus aluminum letter openers. Eventually he asked her what she thought about rape, if she'd ever experienced it. In truth, Angie didn't want to give the guy a ride to Newspaper Rock. She was coerced, she thought. She was guilt tripped. Or, she didn't know how to tell him no.

She was in this tenuous position: she could tell him the truth—and, she said to herself, encourage social awareness—or she could lie (which she noted could or could not be a lie: the truth was for her a shepherd with no training). She was not ashamed. As a veteran of the war over remote-access areas, she knew if she told him she'd been raped, he might be incited. It was nature, or it was human, which might have been the same thing.

Later she would wonder why she hadn't wondered why he asked her in the first place.

Instead, Angie said yes, she had. It started as it always does: Did he jump out of the bushes or did you know him? What were you wearing? Did you kiss him? It headed this way: Did it hurt? Was it so different from making love? How many times? And now, after a moment of silence, something like the meditation method for school prayer, it ends this way: What are we going to do about the sexual tension between us?

She sizes him up—a small man of unremarkable upper-body musculature, weak-minded, nasally. Were you a wrestler? she asks. He was not.

She tells him her anger-management counselor suggests she not speak of sexual tension. She tells him she has been fired twice for kicking the shit out of coworkers and she can't afford to be fired again, —that she will take her counselor's advice, however irrelevant or unreasonable it might be. What with her genital herpes, sexual anything wasn't a good idea one way or another.

She is not so much worried as agitated. A leaning toward social awareness has transformed quickly into a leaning toward fiction. Later she will consider the possibility these sets might share some territory. For now, Angie turns the car around and drives the hostel regular back to Moab, an afternoon wasted.

(f) and (m) stop for gas and water. The man complains the rental has no air-conditioning and it is over one hundred degrees. Too bad we didn't meet in May, he says, or April. The man will fill the water tanks, the woman will fill the gas. She gives him a twenty and tells him to pay for the gas. When he is well inside the Chevron, she takes a bag from under the seat, pulls out a .22 pistol. She takes the clip out and inserts bullets.

In the final sequence, Angie sets up her tent about eighteen paces from the fire pit. She eats a banana. The sage-smelling air is pungent. It presses long feathered fingers into her brain. She feels the campground doesn't want her, and neither does the surrounding rock. She squats. The ground beneath her is alive with small things that crawl. She moves, though the tent will stay.

This morning she traded the Cavalier for a Jeep. The desert, she thought, must be safer than the hostel.

She tried Lavender Canyon. The first few boulders, steps, and washes were gratifying. Then she wondered how she'd get out if she became stuck or if it rained. Six miles down the trail she decided to try another road.

Angie drove back around to Indian Creek. She drove until there were no people, until the sun began to wane and the sign read BEEF BASIN ‡. She didn't know what Beef Basin was, really, but a coworker had said there were a lot of ruins there and access was easy. She came with enough water and food to last almost a week. The road through Cottonwood Canyon was relatively flat and dusty. When she found an empty space overlooked by ruins, she pitched a tent.

She wonders now why she thought she might suddenly like granola. Lack of cooking facilities doesn't make raw oatmeal, sticky with honey, any more palatable than it ever has been. Had she listened to Aunt Bernetta, she would have brought a barbecue and the larger of her coolers. She would not be eating bird food with one hand and stirring a fire by stick with the other.

Above her there are three ruins. Two are barely visible. They are not big enough to be kivas. They are storage bins with windows. The Anasazi must have farmed here, she thought. There would have been corn and gourds and beans (no honey-stuck granola). There would be game fat, clay, sand, and grass to hold them.

Now there are six hundred years of no corn no gourds no beans and the animals are cattle fattened on brush.

(f) and (m) hike to the first ruin. (f) is cautious of snakes though she has never seen a snake personally, or at least not in this area. They drink from canteens.

Isn't that something? (m) says. You can still see their little handprints. Quite the masons, he says, shaking his head. I often dreamt of Native Americans as a child. I suspect I was one once. Maybe I was here.

The woman thinks, If he tells me about past lives I'm going to shoot him right now.

Angie tears that page out of her journal. She throws her banana peel and the page into the fire.

You can still see their little handprints, the man says. He points to a tiny cob of bare corn just inside the window. See? he says. Someone held that.

Don't touch it, she says. He says he wouldn't touch anything inside, wouldn't even reach in there. It's not my house, he says.

The woman decides the man has a nice jaw and well-defined if thin and wiry eyebrows.

Angie has not dated since she quit the plant outside Idaho Falls. Waitressing has made mating a surly negotiation, as has living with Aunt Bernetta and Mirabelle. She lacks friends. She sits in silence for days. Yet she has not felt truly alone until this moment.

She considers also it is not the coming darkness that frightens her. Nightmares, movies, and true-life experiences have equipped her with the know-how to deal with the murderer hiding in the basement, the moving shadow on the street, the phone call in the night. Rather, it is space. Not as metaphor or symbol, but as geographical, impossibly tangible space.

The sun is a bright slash across the horizon and it is still warm.

She lies flat on a blanket beside the fire, a towel over her eyes, an unwanted sandwich at her side, attracting ants.

Four years have passed and nothing to be afraid of. No rape, no stalkers. At twenty-eight she has never broken a bone, never been stung by a bee, and never had a concussion. She cries for herself. There is nothing else to do. She can't hike to the ruins because she's afraid of snakes. She should have brought cards, except she loses at Solitaire. If Mirabelle were here, she could play Scrabble. If Aunt Bernetta were here, she could describe heaven —that is, the whereabouts of her deceased second husband, the gas-lit streetlamps there, the shellfish feasts at every corner, the ice cream churned by singing angels.

The window in the ruin most visible is too human. It terrifies her. The rest—the rocks, the putty, the sticks —that could almost be nature. The window is or has been at one time almost perfectly square, while the ruin edges up along the cliffside, fitting to the form. Then again, she thinks, maybe it's nature that's truly frightening and the window is comfort. I was here. You are here. Or, maybe, that's nature.

She wonders why she decided it was a window. Who would look out of a storage bin? Mice, maybe. Mice crawling in, crawling out. Hands reaching in, hands pulling out. When she was sixteen she'd had a baby. There was significant pain. The epidural didn't work. The nurses could only forget to bring ice chips to a girl putting her baby up for adoption. The anesthesiologist was watching the Superbowl with the nurses and the residents and interns; when he was told by Angie's aunt that the epidural needed to be readministered, he said, Wait one sec. And, Oh! Can you believe it? Just one more sec. So it went until Angie was a nine and the baby, chin caught against her pelvic bone, set off fetal monitors. Too late now, he said. The doctor arrived at halftime. Uh oh, he said. Vertex. Hands went in, a baby came out. Nurses applauded the doctor for the turning of the baby.

Angie asked not to see it—to see her. Mirabelle's neighbor, the adoptive mother, agreed. The doctor smiled, nodded, and delivered her placenta.

Wait! Angie yelled at him. Aren't you going to stitch me up?

What for? he said, checking his watch.

They said I tore. Everyone said I tore. Now stitch me up.

He looked at a nurse, who rolled her eyes, shrugged, pushed the baby cart out of the room and down the hall.

The doctor gave her a couple of stitches and left without another word. Later she would learn he stitched only the outside layer of skin, and then inadequately, leaving her a complete wreck. Had someone provided her a mirror, she might have seen just how bad the situation was.

It was not about seeing, she decides, but holding. Shall I spread you outside or hold you inside. Or perhaps not about holding but about catching the chin of the world. What were you wearing. Did you see it coming. Why would you give it up.

Maybe it has nothing to do with containment.

It's the black window, the exit-entryway, becoming less distinguishable as dusk turns to dark, that has her attention, not the rest of the ruin. It's what is not there that she wants. She wants the food or the hands. The hands with food. History imparts no judgment. Only: A split cob of corn on her lips, a bean in each ear, wet clay on the eyes.

Storage bins, habitats, hiding places, Motel 6. Could be anything.

All a ruin. That which was ruined or that which remains.

Thousands of tourists from well-moneyed nations scour these buttes for ruins, she thinks, lighting a battery-operated lamp. They fingered and finger shards of gray and black pottery and half-carved multicolored arrowheads. Look! they say. A flint tool. Look! A dwelling. Tiny hands pressed here. They look and leave with adoration or they look and leave with pottery in their pockets, the shards of pottery falling away, multiplying like the cells of a fetus from the egg. Then it is nothing and lost.

Your breast is so soft, (m) says to (f), and your nipple feels like a rubber stamp. Your bones are long and well-fleshed. Let me wipe the sand off your face, says (m), who is naked and not thin. And with a Wet Wipes, he does.

Angie's stomach growls. She may have food to last several days, but, she reminds herself, her stay is still optional.

(m) and (f) have discussed childhoods. (m) says there are things he has seen too painful to talk about. (f) has shown him her gun.

Angie doesn't need to overcome anything, and nothing may overcome her. When she returns, she will tell Mirabelle everything, in fact, is optional, and Mirabelle will put her hand on Angie's hand. I'm so proud, she will say. Now, I believe we left off at chapter twenty-three.

(m) shows her a picture of his three kids and wife. The gun is on the bag next to them, and so is his wallet.

Angie doesn't owe endurance, or even rebellion, anything, and they owe nothing to her. She may insist on reading her elders something new. They may protest, but they will submit because she will ask them to, nicely, and because the new romance will be easy on the ears. If it should put them to sleep, they will, at the least, wake up refreshed, not anxious or ill-feeling or torn.

(m) puts the .22 on her empty belly, which is indented red from her new-shorn shorts. He kisses her, lies down beside her.

(f) traces the blue veins of his arms until his breathing is deep and regular.

They sleep like that until the gun, hot from the sun, burns her skin.

Christine has been published in the What There Is anthology, the rough draft, and New Voices in Poetry and Prose, who gave her a first-place prize. She's also won the Crossroads Fiction Contest and an honorable mention from Foster City. Aside from that, the University of Idaho gave her a bachelor's in English in 1993. After the good citizens of Moscow, Idaho, gently but sternly ushered her out of their community, she flew to Tokyo with $200 in her pocket and maguro on her mind. She taught English to housewives and salarymen for a few months. Back in the States, she edited proposals for Lockheed, then moved to Utah to edit books for a few years at Northwest Publishing, Inc. Sadly, the publisher embezzled millions and NPI closed. When she's not editing at CitySearch, she copy edits books for Bantam Doubleday Dell through her company, Sandstone Editing. The University of Utah is currently withholding her MFA in fiction; she hopes to graduate for Christmas, 1997.