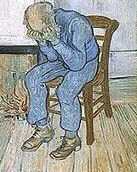

Old Man by Vincent Van Gogh

In the beginning; it starts in bed.

Today a piece of my cervix came out. There was an itching between my legs. I put my hand down there and at first I was surprised. It was small, brown, and crisp. Janelle said, "Let me see it." I am not accustomed to showing such parts of my body, so I hesitated. "You don't have to show me," she said. I showed her. "Wow," she said. "I wonder what happens to the rest of you when you die."

It happens when cells mutate, my doctor said. She showed me a two-color illustration. Enlarged cells. Strange-shaped cells.

But how do they mutate? I thought. Abandon ship. Refuse roundness. At some point they decide to go the other way, either from the inside out or the outside in.

I am small, crisp, and brown. I am a paper bag.

"It hurt," I say.

"I guess it would," Janelle says.

I lay my head on her pliant stomach and trace the outside line of her breast, ribs, and waist. She smells like garlic, but I am used to that. What counts is the feeling I get lying next to her—the feeling of buzzing, of swimming under water.

"The doctor said the Leep procedure would feel like a pinch, but it didn't," I tell her. "She gave me shots to make me numb, but I felt every one—about seven or nine of them—and then I felt the cutting. Jesus, that hurt. She said thirty seconds. It was fifty, at least, and it felt like all day. You know how I don't like strangers between my legs."

"Yeah," she says, "I know."

It took seven months for me to let Janelle between my legs. That was easy, though, because she had no bold or sharp instruments. She was very gentle.

It started with a kiss. We drank two bottles of cheap burgundy and wandered through a statue garden one summer night. I don't remember much about the garden; I was flirting. Dogs barked when we sneaked over the fence. There were a lot of trees and a three-quarter moon. The statues of a sphinx and a tall man scared the hell out of us. We sat near one that looked like a baby cradle and imagined infant sacrifices. The smell of bread baking in the factory next store was stout and seductive. But the kiss didn't come in the statue garden.

At the zoo; bear area.

"It started in Wonder Bread, before the statue garden," Janelle says, "when we held hands." At the zoo Janelle looks bold and healthy. I resent her red striped shirt. "You looked cute in the Smurf hat. So did I, didn't I?" She laughs. She hasn't laughed in a week.

Janelle is enamored with the bears, especially the polar bears. She studies the moat between the fence and the bears.

"Yeah, you looked great," I say, and I mean it. She had all her red hair tucked in a blue hair net. It was two in the morning. We had known each other for a little over three months.

At first no one in the Wonder Bread warehouse noticed. Men stacked bread and Hostesses on tall carts. They worked at machinery. Janelle took a Twinkie from a cart and broke a piece off for me. A man approached us but my mouth was full so Janelle did the talking.

"It's her birthday," Janelle told a Wonder Bread man. "She's dying and before she dies she wants a tour of your factory. Okay?" Janelle has never had a problem with small lies.

The workers couldn't show the dough vats, but they did show us bread baking. "Get your hand caught in that," the man said, "and your arm is gone. Szoom. Gone. Lucky if you live."

I throw deer pellets at the bears. Janelle pushes me and points to a sign: Please Do Not Feed Me.

"It started in Liberty Park," I say. "After Wonder Bread and the statues. On the swingset."

"Yes, the park," she says. We had driven five blocks to the park.

I was afraid. I could sleep with a woman, I thought. I could have sex with a woman. But I could not kiss her. My exact words were: "There is a ten-foot-thick concrete wall as high as you can see between me and ever kissing a woman. And I couldn't have sex with a woman before I kissed her." It happened fast, though. We were drunk, playing spider on the swing, when she took off her shirt in one glorious movement and kissed me. She leaned her head back and her hair tickled my knee. Her lips were bright and shouting, "Busy old fool, unruly sun, Why dost thou thus," even though the sun hadn't risen. Looking back, the kissing wall was never really there.

After the kiss Janelle passed out under the swings. A cop stopped me as I tried to drag her body to my car. "Don't you know this is a stabber park?" he said. The cop could have ticketed us on several counts, especially when we stumbled into my car and an empty wine bottle rolled out. Instead he followed our car out. Either Janelle's breasts impressed or embarrassed him.

I'm tired of bears. They lie around. The brown bear is a mound of fur in the sun.

"I want to see the monkeys," I say. It's unsettling that Janelle does not object. She is different these days. She does not look at me and she does not object to much.

One monkey jumps from a perch and slams against the glass between us.

"He doesn't like us here," says Janelle. "I don't blame him."

"Have you met someone else?" I ask.

"No," she says.

One monkey grabs onto the back of another and humps her. It is short and fast and the girl-monkey is angry.

Her lips quiver and chin dimples in her reflection on the glass. "I love you," she says.

At the apartment, cooking dinner.

"Sometimes I think I want a family," says Janelle. She leans into the kitchen table. "I was looking in a magazine today and read about a kid who killed his mom and dad and baby brother. That wouldn't happen to me, though. If I had a family."

She says it like it's the first time she's brought up having a family. First it was about motherhood, and I thought sperm bank. Then it became nuclear.

"In a couple of months it'll be time to get a new apartment, you know," I tell her. "That bitch manager was here today trying to get me to sign a lease. I told her it was noisy here, dirty, and the pool is never open. Forget this place. There's no good parking."

"There are all kinds of families," Janelle says. "My parents say since I turned gay I won't have them forever. Not that I believe in heaven, well... If I have my own family we'll go wherever people like us go, together, maybe."

"I can't hear you over the beaters," I lie. "Wait a minute." It's my turn to cook. I'm making mashed potatoes and soup. I'm actually tired of Janelle's filet Oscar or cheese pottage.

"I was saying I got in an argument with my mother today," says Janelle. She sighs in an obvious way. I think she is looking at me.

"It started when you walked into class," I say. "You looked like a fairy from a story."

"I didn't look like a fairy," she says. She carves a star on the table with a silver nail file.

"No, you did. You were wearing a long white shirt and white pants. They kind of flowed when you walked."

"I don't remember you," she says. "Not then. Not until the Den. Can you say bonsai?" she asks. Janelle and I met through Yuichiro, a mutual friend and Japanese exchange student. Whenever we ran out of things he could talk about, he demonstrated bonsai with his arms in the air or told us about Japanese toilets. We were shocked anew every time. We exchanged sexual innuendoes and possibilities that our friend probably didn't (want to) understand. "That was fun, playing second-rate beatniks," says Janelle.

"Monkey falls from tree as often as dog hits head on the stick," Yuichiro told us one night. I'm sad I can't see him. It was a struggle to watch him look for words, though, because he was thoughtful and his vocabulary was limiting.

I miss the way I felt then. I liked the good feeling of getting to know someone, the feeling of being drawn to something new and laughing and colorful. I miss the way Janelle bent over the table to listen to me.

I don't like not being remembered. I stir vegetable-beef in a saucepan. It's almost boiling.

"When will you find out?" she says.

"In ten days. The lab reports will be back in ten days to say they got it all, or not. Part of it was mild displasia, part of it precancerous. I hope they got it all."

I looked displasia up in the dictionary. It wasn't there.

Displacement: the vector, drawn between two successive points on the trajectory of a moving object, representing the magnitude and direction of the motion...

Display: to exhibit / (of birds) to exhibit (plumage) in courtship, or aggressively...

"I hope so, too," says Janelle. "Do you want me to go with for the follow-up?"

I shake my head no. Janelle is a little cold. I think she knows how a person usually gets cervical cancer, and it's nasty. Why didn't you tell me before? she would ask. Who knows. Maybe she gave HPV to me. That's crazy. I had it and I might have given it to her. Now she has to check for strange growths and have pap smears now and then.

The storyteller could be anywhere.

You are a stranger to me. Or maybe we lay side by side in our plastic boxes at birth. Maybe our families stood together pointing at us, ogling, reading the name cards to see which was theirs.

You are beautiful at all times. Your hook nose and webbed feet only enhance this beauty.

I cannot say which is mine, this breast or that, but I know I want you near me forever.

When you say you want a child maybe you mean you want a dog. Maybe a puppy will make you stay.

When you say you love me maybe you mean you want to have me for yourself or maybe you mean you want to give yourself to me.

Maybe it is my child you want and not yours.

Heaven is not a place, and neither is hell; you have my word. I love you—how can that be wrong?

When you wake I will tell you I am willing to let you go. Or, if you let me go, I won't hate you. Or, if you let me go, I'll be okay. Or that I will wrap around myself like a ball of string and wait to be undone.

Dad's house.

I was conceived on the nether side of a diaphragm. My mother cried for the following eight months. There were complications. I came early. I had a hole in my lungs. My mother prayed for me. That's what my father said six years ago.

"Does she wear leather?" he asks me. He hides a smile with a glass of wine.

"You're being an asshole, Dad," I say.

"I just think it's funny. I never pictured—why didn't you tell me sooner?"

"Why should I have?"

"I don't know. I could have met her. We could have had her for dinner." He laughs so hard there are tears in his eyes.

"Are you serious?" he says. "My daughter is a lesbian?" He laughs again. "I always thought you were different," he says. "But not that different. She's the butch, right? I mean, you weren't exactly climbing trees when you were a kid. And you're certainly not now." He is rolling.

For sure I can't tell him about the surgery or anything else. I grab my keys and leave.

My father sometimes says I was an accident but he loves me anyway. He says I came out bitching and I haven't stopped. He says I am prone to sickness. More than fifty percent of Americans will have one or more STD by the age thirty-five, he said when I was fourteen, then gave me a six-pack of condoms. I guess I forgot.

In bed, over rolled-up pancakes and milk.

"I had a dream and you were in it," says Janelle. It could go one of two ways:

I was bad and she hated me or we had sex but she didn't come. She doesn't dream much, and when she does it's generally the same two dreams.

"You ran out of the house saying things that didn't make sense." Janelle twists a brown curl around her finger. She woke me up early this morning. She'd made pancakes and was proud of them—it was the first time she hadn't burnt them. She even rolled them up with lots of butter and sugar. I couldn't eat them, though. They looked good but it was early.

"Was it day or night?" I ask.

"I'm not sure," she says. "It was snowing. You didn't have any shoes on and you were only wearing a nightgown. I ran after you with a blanket. We lived in kind of a cabin. Anyway you ran out of the cabin and I yelled at you to wait up. When I finally caught up you'd jumped into a river and you were plunging your arms down there, digging for something. 'I can't find it,' you said. 'I lost it. I can't find it.' I think you said what it was you lost but I don't remember. Then I didn't have the blanket anymore and it just ended. I woke up."

I expect certain things from a dream: life experiences translate into symbols, or seem to, which makes understanding easier. Or there is running-away-from-a-murderer dreams, which can't be accounted for, and quest-for-sex dreams and the rare flying dream, which aren't about life. Janelle's doesn't make sense. It should have been the other way. It's Janelle who's lost it. I'll never leave her.

"Is it something you're looking for?" she asks. She doesn't flinch, doesn't shake. I hate her for this. It's like her life will not change if I say yes. Anyway she doesn't mean it. It's a lead to negotiate who pulled away first. She'll say it was me, and that she just made it physical.

"Dreams don't mean anything," I say. "Good god, don't you remember? Last summer, at the lake. I lost my watch. Remember? Or was it a bracelet? You remember. I said, 'Janelle, get your goggles. I lost it, I lost it.'"

Nighttime; the bathroom.

I like to keep my teeth very clean. My bottom teeth look like crooked grave stones, but I'm okay with that. Rest in peace, they could say. Or, have it your way, dessert first. But I like them white.

When I brush my teeth I think of my mother. My mom used to sit at my bedside and play with my hair. She told stories of her life in Denmark, how coming to America was her first time on a plane, how she couldn't believe people ate corn on the cob when she got here. Or maybe she beat me with a wooden brush and locked herself in my parents' bedroom, crying. My dad will not confirm either account. "You were young," he says when I ask too many questions. "Forget about it."

"Come to bed," Janelle yells from the bedroom. "Turn the light out. God, it's two in the morning."

My mother had false teeth. I remember little about her except her teeth. To tease me she pulled her top teeth out almost an inch so she looked like a skeleton. She would open her eyes wide and hiss like a vampire. I would scream and hide, and sometimes I'd cry, but I'd always ask her to do it again on another day. When she died, we buried her teeth with her.

I braid my hair then get into bed. I lay sideways against Janelle's back. It used to be she lay against me. She takes my hand and presses it against her chest bones. Soon she is breathing hard. It used to be Janelle wanted me. Now she wants me sometimes, but not since the end of April when I cried after sex.

Her hair tickles my nose. I try to not move or twitch or cough. It has been a long day. I'm nervous. Janelle ran errands, went to school. I lay in bed and ate Fritos till she came home at ten. I smoked a whole pack of cigarettes and my lungs are burnt.

On the bus, route 4; back seat.

"It's that I have HPV," I say. My flesh is cold then hot then cold. I stare at a man's head three seats up.

"What's that?" she says.

"Human papilloma virus."

"I mean what's that?" She's calm. It's a trick.

"It causes growths."

"Growths? Come on, what is it? If I'm going to have growths I should know what to call them."

I am hot then cold then hot and cold. My fingers are caught around my book bag. I can see right now I have picked the wrong place to tell her.

"Can we talk about this later?"

"It's important, you said. Come now, you said. Now go on."

"Genital warts." It comes out fast. "You might not have it." She is quiet. We sit like that—quiet. We bounce around as busses do. I expected anger and maybe I have it. "Say something." But she doesn't. She gestures with a hand but I'm not sure it means anything.

In the desert; Needles district.

Janelle shakes me awake and points to coyote prints around our sleeping bags.

"Must not be worth eating," she says, and I feel just like that.

I sit up in the sleeping bag. There is just enough light for me to see the outline of the cave mouth and Janelle's truck outside of it.

"You said you wanted to go with me," she says. I nod and search the bottom of the bag for my jeans.

The rock is slick and my boots are cheap. "Wait up," I say.

Janelle plants her tripod on the side of the outcrop. "Hurry," she says. "The light is just right."

The light is just right. The slim sunrise makes the rocks turn red.

When we reach the top I can't breathe. I bend over and exhale slowly. Janelle is quick with the tripod. The desert is quiet. The putting together of camera parts is loud. The clicking of shots and the slow shutter are loud.

Last night Janelle said we are guests in each other's lives. We do not need each other but rather like the company. She will leave me soon. Telling her will make it sooner. She will find someone new. There will be small intimacies, and then fond memories. Janelle will be honest. Check yourself for HPV, she'll say. My girlfriend had it.

It's not a big deal. The actual growths don't hurt.

My fingers, her fingers. My tongue, hers. Mild exchanges and pleasant utterances.

Ted Hughes says in the womb it met maggots and rottenness. I consider my rottenness.

Janelle will have her family. She says a family without a father is no good. I told her a kid raised by lesbians would never know any different. A girl-child would appreciate the novelty. A boy-child would feel loyalty to his mother, no matter what. I could be the father. Or if she preferred to be the father, I could be the mother. Two fathers, two mothers. It could go in any of several directions. I know how to change diapers.

I don't want someone new. I want Janelle new. I want a new vagina. I want everything new. I want to smell like an unfinished basement.

Coming home; the old playpen, pad, birds' nest, grotto.

It's not for me I kept this fossil. It's for her a stem and little lines and I don't have a bag to put it in. She took her bag and she took her books and clothes her purple table. She took the apples and three bagels and I think she took my Utes shirt I hated it anyway it never fit it shrunk under the armpits—she is smaller than me.

She is smaller than me and I think I should at least get a note. This fossil, this evidence of desert history, it could have been a paperweight for notes. Instead she left and did not say good-bye or even I love you. Did not say I found a father. Did not say didn't find a father but I don't want you either.

Father thinks I'm funny.

The room is not less full in fact fuller. My papers are everywhere—opened envelopes, photocopies, text.

The wax lion broken in a hundred orange pieces messes up the bed.

And I shouldn't have. Should not have made a lover out of Tim her brother. She was leaving anyway. Told me we are guests in each other's lives. It was one night.

And anyway a favor. Now she can have her father. Now she can rather leave the company.

It is for her I kept his company.

A couple months later; the new apartment.

God says, Nothing moves me anymore. Why don't you do something wicked. I stand on my roof outside my attic window, survey the people who wait by my house at the bus stop. I yell to one, Hey lady, when you breathe your breasts dive in and out of eternity like two whales in love swimming next to each other.

I hear God laughing in the westward clouds, clapping his big pale hands. I feel the sun set on my shoulder. I am a limp and drying noodle, dangling from the sky.

This is the place where I come to think and daydream. Mostly I think about you and dream you will come back to me. You will love my new apartment and wish to stay here. Other times I sketch sparrows or imagine romances: A stranger who hasn't shaved in a week rumbles into town, falls in love with a girl in the park. He follows her everywhere, notices her hair drifts behind her like brown flags. He strums the Spanish guitar and sings, You taste like honey, you can have my money, let's run away together.

Today I'll say a romance for you: I saw us two under a sandstone overhang. Our hands were empty and dry. I smelled water on rock. Flute music echoed into our cave. The god who would feed us had come to make his rounds. I looked at you, you looked past me, I left to find him faster.

I found him curled under sage, bent around three million seeds of corn. His horns had shriveled. His skin wrinkled around his bones. He explained: "I've been meaning to plant my seed..." I spotted his flute in the sand a few feet away. I put it in his hand. "Play for us," I said.

I look for you in the morning and again in the evening. I call for you from my roof and sometimes my calling comes out in throwing rocks at birds or staring south to the city. I listen carefully to the wind, trying to imagine what you'd say, listening for what I imagine you say.

Christine has been published in the What There Is anthology, the rough draft, and New Voices in Poetry and Prose, who gave her a first-place prize. She's also won the Crossroads Fiction Contest and an honorable mention from Foster City. Aside from that, the University of Idaho gave her a bachelor's in English in 1993. After the good citizens of Moscow, Idaho, gently but sternly ushered her out of their community, she flew to Tokyo with $200 in her pocket and maguro on her mind. She taught English to housewives and salarymen for a few months. Back in the States, she edited proposals for Lockheed, then moved to Utah to edit books for a few years at Northwest Publishing, Inc. Sadly, the publisher embezzled millions and NPI closed. When she's not editing at CitySearch, she copy edits books for Bantam Doubleday Dell through her company, Sandstone Editing. The University of Utah is currently withholding her MFA in fiction; she hopes to graduate for Christmas, 1997.