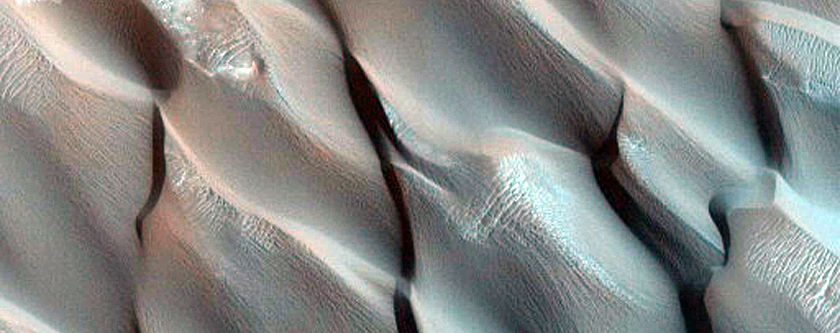

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

Was just folding for the day when my secretary called through, there was a Mrs. Lincoln to see me. Three o'clock. Our court came up at half-past. Al was already there and changing. Don't know any Lincolns, I said. Sue's voice came back.

—You will know her when you see her?

—I doubt that, I said, but all right, call the Club and tell Mr. Fish to find another player, I'll be over soon as I can. Snapped my case shut anyhow and got up to put on my coat and tie so Mrs. Lincoln could see I was already on the way out. That quizzical note in Sue's voice had suggested a questionable party. There's a broad works the building three to five-thirty, but Wednesday's not her day on this floor. Nineteen, she says, and majoring in political science at UCLA, but, like she runs this Corvette and rents a pad in Beverly Hills and there's also the shrink to keep. Hard worker. Writes herself a tight schedule three days a week through these suites of investment managers, accountants, agents, brokers and lawyers. Still, she says, manicuring wouldn't get her through college and all, would it? These kids.

Or was it a divorce? I don't do divorces. Industrial parks, shopping centers. Ten percent after taxes. Real estate is one of the easier ways to practice law in Southern California, though for sheer indolence, professionally speaking, those remittance men in San Francisco have a head start on us, 100 years to say the least that money's already been made. Up there above the fog belt in Marin County, my fellow attorneys are on the courts five days to my three. I like it here though. I was brought up in Los Angeles. It's open, still new. That's what Easterners complain about, I know. It's this newness disturbs them, the sense we're still a first generation, lacking roots or history, that these sunny days of ours with their long, mild, limpid, and vast nights are uncrowded by the ghosts of all those who have lived and died struggling to provide us with a certain resonance, a moralized background, if you like, though the weight of it can seem dense and choking, as it does to me. I suppose it is new, very much so compared with Boston or Charleston or New Orleans, where you feel roots as dark as an old death. And I suppose it relieves me to know sensational human dramas are manufactured right here in the studios for world export. On the other hand, your garden variety of business lawyer does run into an occasional gamy situation, the kind of thing you'd rather watch cleaned up enough to be put on film and distributed with an X label. There is more than enough history for that, even here.

A slow, heavy step came down the corridor, paused outside. Deferential knock. I told her to come in. It was a black woman, about 50, tallish, very stout, with an enormous bosom and heavy arms, her short hair quite grizzled. Plain brown dress and broken shoes. Couldn't place her at all, until she reminded me she'd worked for us about ten years ago, nursing and light housekeeping when my mother was in her long, terminal illness. Colerado Lincoln, Colly. She'd lived in the guest-house with Mother, and I'd been traveling a lot at that time. But she'd aged so, and put on lots of weight. I recalled how she carried that nurse's black bag with her everywhere, and here she was, still toting it. The same one, cracked at the seams, the leather breaking from the frame. Then, when Mother died, there really wasn't anything for Colly to do, and we thought it would be insulting to suggest housework or picking up after the children for that matter. She offered the latter, but only to be kind to us. She was that sort of considerate woman, willing to do herself injury to be of service to others. Then, a few weeks later she called to say she'd gotten a nursing and companion job down the Coast in La Jolla with a single lady and thanked us for having let her stay on in the guest-house. That was the last time we heard from her. Now she was here, looking poorish and much too worn.

She sat down heavily like a big old bronze casting, cracking in its segments and wheezing, opened her bag deliberately between her legs and took from it a manila envelope, studying its address as if it had just been delivered to her. I went over and took it. It was wrinkled and creased, the postmark told me she'd had it in her bag several weeks, and it looked like she had opened and closed it again and again, the clasp snapped off. Inside it was another envelope, letter-size, sealed with scotch tape. I asked her permission to open it. Inside was a letter, which was wrapped around a thick white envelope, also sealed with tape and held by a crumbling rubber band, her name scrawled on the face in block letters with an orange crayon. The letter, printed in the same crayon, was short:

Dear Colly,

You know I love you, only you. This is all I can do for you now. I'm sorry, truly sorry. Forgive me. You did all you could for my body. Now pray for me. Poor Colly. Poor, poor me.

Lorna Ramona de Lourdes Ewing.

I wondered why she hadn't opened this last envelope.

—I was afraid to, she said.

—But it's for you.

—I was afraid to.

Asked her if she wanted me to open it for her. Her eyes, small in their puffy sockets, were tired and tearing. She nodded.

—Poor thing, poor thing, she said.

It was a will, properly signed and witnessed, dated two years ago. I read it over quickly. Except for some fair-sized charitable bequests, Lorna Ramona de Lourdes Ewing had left everything to Colly. And everything seemed like quite a lot. A gold mine, three hotels, one in Santa Barbara, one in Los Angeles and one in La ]olla, four parcels of Mexican real estate that would total over a quarter-million acres, jewels and a strong box with cash in it, the receipt for the tally reading 77,000-odd dollars. I told Colly she was, according to this document, a rich woman, very, very rich—she could buy and sell me and my syndicate twice over and never miss a dime. Tears were running down her cheeks, and the sound in her throat was a choked sobbing, though if she laughed or cried, I couldn't tell.

—But you're rich, Colly! I said.

She put her face into her hands.

—I don't think so, Mister Lazarus, I don't think so.

—Why?

—Couldn't happen to me.

—Well, it has. Why shouldn't you be lucky? After all.

—You don't understand, Mister Lazarus. Then, as if she'd just realized that this will meant her benefactress was actually dead and buried, Colly took a crumpled hanky from the sleeve of her dress and wept heavily in it.

—Poor thing, she gasped. Now I know, now I know what happened. O dear lord Jesus!

Took my coat off and went to sit beside her. Asked her to tell me about it, and she did. Five years, she'd spent five long years down in La ]olla with Miss Ewing.

—A beautiful place, she said, Spanish-style house and big grounds. Old California, a dozen acres saved out from the Rancho de Lourdes. And Miss Ewing? A single lady. Lots of family scattered about: aunts, uncles, what seemed like dozens of cousins and second cousins and removeds, all people with the name of Ewing attached to them somehow. Every Christmas and Easter, like flights of pigeons homing in from Oregon, Washington, and Alaska and Hawaii, Ewings fluttered into the mailbox. She opened every card and note, wedding announcements and funeral notices, and checked them off in a ledger as though she counted heads of livestock. She told Colly stories, mean and funny stories, but mostly funny ones, about those Ewings, but wrote not a line back to any of them, not ever; never had anything to do with them and never would. Miss Ewing and Colly spent all one spring working back through that ledger, collecting and collating Ewings big and little, male and female, and pasting them up into a great folio. Those Ewings had a way of sending snapshots of themselves and their kin as they proliferated and recombined and dropped off, as though they knew Lorna Ramona was going to catalog them in an album some day there in the old house, just as if she were garnishing a Mexican tree of life—one of those pretty clay constructions with its intertwined thicket of thorny branches, and on each thorn a Ewing impaled. Took them months to get them sorted and laid out and mounted, Colly said, simply because, well, Miss Ewing drank. Fact was she drank too much.

—That's why you didn't recognize me when I first limped into this office, Colly said. Oh, she knew she looked mighty different to what she was when she worked for us. It was a gin shuffle. Night and day she'd had to help Miss Ewing. That was her job, and she was her companion. And, it being against her religion—Colly was a Witness—she'd never touched liquor before. Oh, it was bad, but toward the end it got worse.

There were the times when the poor woman had those gin spells and pretended she didn't know Colly and would torment her, even hit her. Colly understood, and she'd not hurt her, not really. And she'd been like a mother to her, too, holding her and comforting her. The old lady was more pitiful then, because after the drinking and fighting, Miss Ewing clung to her and wept with remorse like a child. And she began to run away about then. Not far—there were one or two bars she headed for in San Diego—and Colly would take a cab down and bring her back. Once she was away a week, and Colly was going to call the police—they knew about it, too—when she came home very sick and bruised. That is, she was brought back by a woman, a Mrs. Hansen, she called herself. Plump, blondish woman in slacks who didn't say anything about where she'd found her or when. Colly had taken Miss Ewing right up, undressed her and put her to bed. That's how she saw the marks.

—Marks?

—She was banged up real bad, Colly said. They were black and blue bruises, lumpy, the size of fists: on her breasts and all over. But the marks on her back were long welts, some seamy with dried blood. Colly said she knew what they were: she'd been stropped, from shoulders down to the back of her poor thin thighs. When she'd finished tending to her and given her vitamins and pills for sleeping, she went back down. She felt misgivings. Her heart was beating hard. That Joan Hansen was waiting. She'd been wandering through the house, those bulging, no-colored eyes taking it all in. Colly told her she could go. She liked her not one bit.

Hadn't she asked where Miss Ewing had been? Oh, yes, she'd been considering talking to the police anyway, but then thought, better not, when that Mrs. Hansen said, looking right at her funny, that Miss Ewing had come home of her own free will, that she'd even had to talk her into it.

— Well, did she know where they'd been?

—That's just it, Colly said, I asked her twice, but the way that woman talked, I knew it was lies, so I left off.

—What then?

—I got rid of her, and it wasn't easy, she said. I wasn't going to shove her out, even if I had a mind to do just that. But you know, Mister Lazarus, it isn't exactly the best way to do, laying your hands on that type of woman. I knew what I should do, but you see I had to think of Miss Ewing, too... and things had reached that point where I wasn't sure but what she'd round on me. But I should have... I know I should have. I was just afraid to, that's the truth. And now she's dead.

She told me the rest then. It was what you might expect. In a couple of days, Miss Ewing came to herself and was contrite and just as sweet as ever. There was no point asking her about her injuries, so Colly said nothing even while she bathed her and walked her about the grounds. A week later she disappeared again one afternoon. Most uneasy in her mind about what to do, Colly waited a few hours, until a cab pulled up and she saw Miss Ewing and that Mrs. Hansen getting down. She could tell her employer was drunk, but that woman Hansen showed no signs. The driver brought a couple of cheap paper suitcases out of the trunk, and Mrs. Hansen took and opened Miss Ewing's purse, plucked a bill out and paid him off. Lorna had asked her to live with her, she told Colly, and then they went right up the stairs together.

—Mister Lazarus, I read the handwriting on the wall. I knew it was bad. When I heard that, I knew it was bad news for me. That Joan Hansen was hard and mean. From the moment she walked into that house she had set her mind to get rid of me. First thing she made me move downstairs. I hung my clothes out ready to go just as soon as I went down, you know, behind the kitchen. It wasn't but three days before she came in on me one night after I was asleep—they'd been up there drinking steady two whole days by then, arguing like cats—and no, I wasn't listening to them, neither, because I knew what it was all about, I can tell you—and then just like that she shook me up and told me to pack up and go. Handed me my next week's pay and paid me off, though the way she did, I could see she preferred to keep that little bit of money for herself. I put my things straight into my satchel, and I left. Didn't even see Miss Ewing. After five years, Mister Lazarus. Five years! Lorna says to tell you goodbye, Colerado, she doesn't want to come down this morning anyway. Well then, I'm going up, Mrs. Hansen, I said. No you are not, she said, and blocked the stairs, and don't you even think to try getting past me, you black witch, she said, those popping, rust-colored eyes snapping red fire at me like the devil's own. It broke my heart, Mister Lazarus, but what could I do? I saw what it was, so I left. Came back up to LA. I left my address with the gardener though, told him to be sure to give it only to Miss Ewing herself, and he promised.

—That was all?

—That was all, Mister Lazarus, except....

—What, Colly?

—Except about a month ago, I think, when I got these papers in the post, she called me.

—Who, Miss Ewing?

—Miss Ewing called me. Yes, she did. Long distance.

—What did she say?

—Nothing, Mister Lazarus, she didn't say nothing.

—I dont understand you, Colly.

—I am saying just what I mean. I was going to sleep, so it must have been about 11 of the clock. Phone rang, and I heard the operator talking, and then I heard the money going into the box, and she said to go ahead now with your party, and I heard Miss Ewing's voice, and she said, Colly, that you? Yes, it is, I said. Who is that? Is that you, Miss Ewing? Listen Colly, she said, I miss you. I mean, I need you Colly. I want you to do this for me right away tomorrow, I mean, right now Colly. Will you do this, please Colly? And I said, Yes, what is it? And then we were cut off, the line was dead, Mister Lazarus, like somebody had clapped down the hook, you know? I was scared for her. I didn't know what to do. I was scared for her, because her voice, Mister Lazarus, that little girl's voice she used when she was feeling bad and sick, it sounded so miserable and, well—she sounded so desperate. I know it now. But I didn't know what to do then. I was up the whole of that night worrying. I prayed for her the night through.

—Didn't you go down?

—No I didn't. I knew I couldn't get in even if I did. That was a mistake, you think? But how could I? I thought and I imagined all kinds of dreadful things; but how could I help her even if I went down there? Look at me. How could I? Then these papers came for me, and I was afraid to open them. I knew it was a bad sign. I waited, and I waited, hoping she might call me again. Was that foolish? Last night I had a thought she wasn't going to call. So I came to see you.

—You did right, Colly. I think I'll look into it. And if you want me to be your lawyer and take care of this, I'm glad to help you, I said.

—Mr. Lazarus, I can't never thank you enough.

—Don't, Colly. It's nothing for me.

—But... how will I pay you?

—That's part of this whole business, so don't you worry about it.

—I mean to say, Mister Lazarus, I think it won't work out.

—Why not? Looks all right to me.

—I don't think so, Mister Lazarus, she said again, I just don't think so. Maybe you shouldn't trouble yourself over me.

—Just don't you worry, Colly. You're going to be very rich. Very rich.

She got up, swaying slowly to her feet. At the door she turned.

—You know I'll be grateful to you, no matter how this turns out, Mister Lazarus. But—well, I know it's going to be bad. I just know it.

I smiled to reassure her, but she only shook her head. I got the feeling she might be wiser than I. There would likely be a hitch somewhere.

Hitch there was. When I got downtown to Probate the next morning to file that will, I was caught up before I'd written out two sentences. The clerk had the name Ewing right at the tip of his tongue: a will was already placed in San Diego. Another will? Yes. Testator one Lorna Ramona de Lourdes Ewing.

—That a fact? I said.

—Not only, the clerk replied, but they're going to have their work cut out notifying all the Ewings on the West Coast: I got a list of 99 in Los Angeles County alone. I thought I'd better go look into that will right away. Called the office and cancelled my day. Told Sue to call Al Fish and scratch tennis from the rest of this week's calendar. And to get on to Mrs. Colerado Lincoln and ask her if she happened to remember any close Ewings in L.A., I mean blood-close Ewings.

—Blood? Sue said.

—What's thicker than water, I said.

—Ketchup, she said. But I know what you mean. Which Ewing would a Ewing talk to, if a Ewing talked to Ewings?

—Right, I said.

Got back in the T-Bird and took the 405 down, 100 minutes. Probate in San Diego had the will, filed over a week ago. And it was freshly minted. Properly made and properly witnessed three short weeks ago. Within the month then, Miss Ewing had been on the line to Colly from a booth somewhere, and she had been cut off. And then? And then she was dead. Interesting thing about this novel document was of course its changed directives: the inheritor was Joan Hansen, and Joan Hansen was not only the sole Beneficiary of the Ewing Estate, but its Executrix as well. Not a jot of those millions to the Church nor a tittle to her charities as a concession to Saints or conscience. It was simple and clear, and it looked tight. Too tight. So tight I thought I might as well look into it while I was there. I said to myself, Who knows but there might not be some mistake, if not in the fixed and iron past, then one that still could be made by pushing at someone who was hasty and altogether too greedy.

I was in it now, so I might as well be optimistic. Started with the lawyer. Telephoned and drove to his office. Found what his voice had told me on the wire: a young man, not so much uncertain as silly, as if he thought he'd make his first $100,000 from the Ewing estate from fees alone. And he just might, if he were luckier than he was smart. A couple of questions put to his putty-flabbed face, and the sweat broke out on his balding head and those black hornrim specs started slipping down his nose. No, he hadn't known there was already a will. Not at all. No, he had never heard the name Ewing before. He was just starting out in San Diego, a Fresno boy, fresh out of Hastings. The Legatee had come by to see him, taken him up to the house in a cab one afternoon, the day the will was made in fact. And he smirked to himself, self-congratulatory. He'd been retained for six months, had it in writing. Had it been he who obtained the witnesses? Again, no. They were there when he arrived, a doctor and some RN. No, he hadn't gone to the funeral, but neither had he been asked. Did the Testator look all right to him that afternoon?

—Well...

—What did that mean? I asked.

—Well, yes.

—Why the hesitation, Mr. Rogers?

—Well, the Testator...

—Miss Ewing?

—Miss Ewing, of course, had seemed somewhat... unhappy... Yes, that's the word, as though...

I pressed him, a bit unfairly perhaps. After all, he didn't have to say anything to me, not yet anyway, if he didn't want to, but he was new enough to the profession to be unsure about what a conscience was, or what to do with it if he found he actually had one. He thought about it. I stared at him, waiting him out. And he fumbled it out: she was in bed, Miss Ewing, that is, and she had not been dressed but was in a robe and nightgown, not fresh at all, crummy in fact, for a woman with so much real property and so forth. That is, her bedclothes didn't look like her sort of stuff at all: an old dirty pink flannel robe and a quilted gown, stained, the padding sticking out under one arm, and much too big for her, as though she'd borrowed them. Her hair was greasy, even ratty; she was pale and very thin. She just looked, well, unhappy.

—Doubtful, you mean? She really hadn't wanted to write up a new will?

— No. Well...

—Reluctant, then?

—No, not exactly. And she went on mumbling about some Colly she wanted to remember.

—Didn't that concern you?

—Yes, it did, but...

Then he clammed up. It must have dawned on him that the matter I had come about involved that very Colly. He stopped. He dug in his heels. I saw that was as far as he'd go. He'd just realized he was Hansen's attorney, though I felt like telling him I'd bet his entire retainer double or nothing he wouldn't be moving paper re Ewing much longer. I put a heavy question to him.

—Who ever taught you it was all right to draw up a will with someone who was not only laid out like that but obviously sick enough in mind to need to be prompted item by item?

Silence.

—Well, Rogers?

—Who ever said she was in bed?

—You did.

—I never! We were all in the living room. Testator reclined on the chaise longue.

—Oh, I said, thanks. I like that, I really do like that, I said.

—What're you getting at? he wanted to know.

—Nothing, I told him, just nothing. Not really.

—If you're thinking to challenge this will, he muttered, turning pale suddenly and beading sweat, you've got one hell of a nerve.

—How would you know what I'm thinking? I said. And got up and walked out. These kids! They grew up with Perry Mason on the TV, and all it takes to throw them is a chapter they haven't seen yet in a rerun.

Next call, the MD. Also what I expected: a rotten building still standing near what was once Old Town, its stucco a 60-year old, washed-out gray and peeling off in chunks, weeds growing through the cracked walk, and grass parching in weedy clumps two feet high. Only patient in his waiting-room a strung-out merchant seaman with a missing right arm. I went through and found him snoring in a tattered, leather armchair, head thrown back. Nice witness: 80 years old at least, a scarred and scabby desert tortoise, and as blind as one. Peevie must have been writing Rx scrip for opiates for a living. I had to lean over and tap at his hearing aid. He twitched awake. Of course he remembered Miss Ewing, of course!

—And you were the physician in charge of her? I said.

—No, no, she didn't need a doctor, she was just fine, fine. Good girl, a little shy, you know, spinster type. No big eater, for sure.

—She's dead, I told him.

—That a fact? My, my. Pity.

—You witnessed the will she made, Doctor Peevie. And I'm her lawyer.

—No, he said, her lawyer's a young fellow, Rooger or something like that. Balding. You've got your hair still.

—Lawyer on the other side, I said.

—That a fact? Well, what can I do for you?

—Tell me one thing...

—I already told you, she was in excellent health. A bit on the skin-and bones side, but otherwise...

—What about her mind. Was she in her right mind?

I tried it out for the record, though I knew what my answer would be, coming from that decrepit chit-scribbler.

—Certainly Miss Ewing was in her right mind. Certainly. See here, Lazarus, or whatever you call yourself. I've been in medical practice since long before your father got off the boat. You think I'd stand witness to a paper if I thought otherwise?

—Dr. Peevie, I said, I think you'd sign your own death certificate for 50 bucks. That's what I think.

—Get the hell out of my office, the old bastard hissed. You ain't welcome on these premises no longer. He struggled out of that broken-down recliner. Get out before I throw you out, goddam mockie foreigner! By Jesus, we'll put you down yet, you dirty bloodsuckers...

That was one witness down. I went after Mrs. Browning next, who lived on the shore on my way north. It was going four, and I wanted to beat the traffic and get to Beverly Hills in time for dinner. I tooled up the Freeway and headed west at the Oceanside turnoff. That's another of those beach towns dying since the Freeway went through. The traffic bypassed, it was now going to bars and cheap motels for the Marines from Pendleton and trailer parks. There were a lot of real estate signs up. In a few years the speculators would have bought it out and set it up for the next wave of luxury rebuilding as LA sprawled down through the Irvine Ranch to join San Diego. Mrs. Browning was in one of those trailer parks herself. Another old-timer, social security and occasional day-jobs nursing. She probably wasn't even licensed in California. Decent woman though. South Dakota. She made me a glass of iced tea. Told her who I was, and she was willing enough to talk about Miss Ewing... at first. Some neighbor who'd pulled out last week had got her a temporary down in La Jolla, but she'd been let go after a few days. She could see the patient was a nice woman, yes, she was nice. A little nervous maybe? Yes, she'd witnessed the will writing that afternoon. Actually, she'd been intending to get out of it all that very morning, but her employer asked her to stay the day.

—Who, Miss Ewing? I asked.

—No, it was that other woman... she'd already forgotten the name.

—Mrs. Hansen?

Yes, she hadn't liked her at all, wouldn't have stuck it out in the first place except that she thought the patient could use her help.

—Why, wasn't she well?

—No, it wasn't that.

—What, then? I said.

And I got it out of her, despite her stumbling hesitations and lip-biting, the picture came through. Miss Ewing was well, yes, but then again she wasn't. Not just the liquor. She guessed she'd seen enough of that kind of thing after nursing 40 years in South Dakota, Lakota drunks and all such, to know about liquor. It was just that... well, the day before the doctor came, and the lawyer, she'd been carrying a tray of tea and toast upstairs—Miss Ewing hardly even touched those, but she tried to get her to take a little now and then—and she'd come upon, well, it wasn't right to say. I asked her what had happened, and she said she had come upon an unnatural scene. I persisted until she let it out.

She'd gone into the upstairs bedroom, Mrs. Hansen's room, and seen them. Together. In the bed. Miss Ewing had said nothing. Her eyes were wide open; but she never moved. But that Mrs. Hansen, well, that woman, had just leaped up like some beast, screaming at her, knocked the tray from her hands, turned her about, thrust her from the room and slammed the door. Mrs.Browning had been shocked, yes, but what was worse as she crept down the stairs was she heard the most awful sounds up there. As if she was beating her. Not a word, not a cry, just the sound of beating, a strap or stick. And then silence. Mrs. Hansen didn't come down that night. The house was silent as the morgue. It was a morgue... except for the animals. That was another thing she hadn't cared for.

—Animals?

—Dogs and cats. All over the place Awful animals. She wouldn't have stayed an hour longer, she said, but she had her pay coming; as soon as the witnessing was done she took it and cleared out.

—Miss Ewing is dead, I told her.

—Well, I'm not surprised, she said.

—Why do you say that?

—I'm sure you'll see for yourself, Mister Lazarus. You seem a sharp-enough young fellow.

That was all she would offer. I said I thought I would go and see for myself.

—You do that, she said. More tea? The fog is the worst thing about living on the ocean, I think. But it's too cold for me now in South Dakota, or I'd go back home.

That evening I called some of the Ewings Sue located by talking to Colly. There were three in Los Angeles. Two were second cousins. When I told them there was this troublesome matter of a pair of wills, though neither offered much chance there'd be a direct substantial bequest for them—so far as a literal reading of them went—though it was entirely possible regarding one of them the chief legatee might see a way to shares in the handling of the Estate if they came in to help me at this point, et cetera... they turned me off, saying they could afford to wait till I had more interesting news to report.

The third Ewing was a first cousin. She expressed at least some feeling when she heard Lorna Ramona was dead. She even invited me right over. It had been a long day, but I thought I might as well go, if only to see what a Ewing was like. The address was next door in Holmby Hills. I was taken by her voice pitched over the phone in a casually authoritative way that had sounded unmistakable undertones of having had a certain kind of schooling beyond the borders of Southern California. It was a voice paid for with the sort of income her people skimmed off a good chunk of its land, sweated out of migrant labor or pumped up from its wells. After all, her married name was Falks, and Falks were problems you ran into in the real estate game. Still, when I saw her, I liked her. She was a turned-out, tall, blonde-skinned woman with big Spanish eyes, soft, black, heavy-lidded. She had a well-done home, too, quite a number of good pictures and some impressive bronzes.

I made it clear from the start she would have little to gain inquiring into Miss Ewing's testaments. Once the relatives picked up the scent and ran baying for their piece of the action, it could entail cutting in hundreds of Ewings. That would allow room for a hell of a lot of law-play, which would reduce their shares, well, to crumpled paper. She said that didn't concern her; besides, most of the Ewings were simply too remote, too removed, or too rich to care. They had always notified Lorna Ramona of their existence not because they anticipated any eventual legacy, but out of a family custom begun by the first, the head of the tribe, Major Major Ewing, USA. He had come out west on Lincoln's express orders. The letter was once considered a family prize. After having lost three important engagements and most of his regiment, he'd confirmed his reputation as a fool and snob by his fierce opposition to the giving of the great command to Grant. Some of his fellow West Pointers had in fact suggested he was really not stupid but subversive, and that was why he had stayed on to fight with the Union Army instead of returning home to the hills of South Carolina he'd come up from in the first place. Be that as it may have been, it was logical to rusticate him to Los Angeles for the duration where he could harry them with his dispatches while Grant won the war. He occupied a rancho owned by the heirs to the Spanish Crown Grant, married the widow of the Señor de Lourdes, a California grandee 20 years older than he, and produced one son, who lived to see that they perched atop that enormous oil pool in the heart of what was to become Los Angeles. And Lorna Ramona was that silly man's only great-grandchild. The cards and photographs were a tradition originated by the Major's orders: he was going to increase and multiply, he had declared, among the alien Latin's cattle and corn, so they were all of them thenceforth to be Ewings united wherever they were. They kept it up more as the family joke memorializing their ancestor and name-giver, that fat and pompous Major Major, than out of any concern for their own collateral relations. It must have been as irksome to them as it was to her. Perhaps they kept it up out of spite to his memory, who knows? Poor Lorna. She stuck to the house on the San Diego end of the property, the Lincoln autograph and the spreading "corporation" that came out of the Major Major's marriage. They wrote, and she never replied. How she must have hated him and them all for it. That is what Mrs. Honor Concepcion Ewing Falks talked about that evening and continued into Friday morning as we drove down to La Jolla.

She'd proposed coming alone with me. She wanted to see the old place again because she hadn't been inside since she was a youngster. That had been an unhappy occasion, too: Lorna's mother and father had been discovered upstairs in their bedroom one morning by their daughter. It was said they'd committed suicide. Mrs. Ewing Falks doubted it. Now that she was grown and thought about the family stories and her own recollections of Lorna's parents, who were socialites, if you can describe any West Coast people by such a word, even fourth or fifth generation "founders," she didn't quite believe it, she didn't know why. But if it were true, then it must have been out of mutual loathing. They were themselves first cousins, if not actually half-brother and sister. The Major Major ran a tight company, organizationally speaking, even if it was a little queer in its notion about who set standards of propriety for whom. She had come to think it was sheer, selfish snobbery, period. No one was ever good enough for him, though he was good for nothing himself but to luck out in the end on the Rancho de Lourdes.

—Do you understand? she asked.

I understood. Though not why she was telling me more than I needed to know about Ewings. Or so I thought as we tooled down through Orange County. Anyway, she'd been passing by La Jolla last year on the way home from a week in Coronado, when she decided to stop by. Falks hadn't wanted to, but as he was still soggy and she driving, they went. It was late afternoon, the gates locked. The house looked altogether shut and desolate, though there was a light burning in the portico. She blew the horn. Then, upstairs, where that bedroom is, she saw a curtain moving. It was lifted slowly aside, and she saw a woman's face, Lorna Ramona's, she was sure it was hers. The head turned from side to side, its mouth opening and closing—like a fish gulping, like a silent screaming. And it suddenly disappeared as the curtain dropped back. She blew her horn again and again. She had Falks get out and rattle the gate. Still no response, no way in. Dogs were barking somewhere in that house. So she'd backed out and drove home to LA. She pitied her cousin and thought of telephoning. In the end, hadn't. That's why she was coming down with me to try to see what Lorna's end had been like at 40, still young for a woman...

—Isn't it, Mister Lazarus? she said, turning her trim, tennis body, her tanned arms and face half-toward me in the car, as if to ask for approval of her handsome Ewing-Falks money-beauty, beauty-money.

— Yes it is, I agreed, though maybe not for another woman.

—You're wrong, she said. Lorna was a beautiful, beautiful girl. We passed for twins. After she was orphaned, she lived with us for a while, and we spent summers together in Santa Barbara and Switzerland. But I haven't seen her in 20 years. I mean, after I was engaged to Falks. She wouldn't come to my wedding, either. I never heard from her or saw her again, unless she was that dreadful face at the window.

So she'd been that close to her. Or, close enough. I'd mentioned the two wills the night before, though I hadn't given up Colerado Lincoln. I was glad I'd left that matter obscure. Perhaps Honor Concepcion Ewing-Falks wouldn't be any help in saving the estate for a poor old black lady named Colly Lincoln, who deserved that inheritance if anyone did. Lorna Ramona had taken it all out of her in the way nothing can redeem.

In La Jolla Mrs. Falks directed me south round a new district mushroomed like the others in a ring around where the University's gone up, off a side road that zigzagged up a steep hill overgrown with brush. I could see the house at its crown through a straggled grove of old oranges and avocados that had grown immense and shapeless and cast limbs around them. The drive was 1920s vintage concrete, cracked and potholed. At the summit we ran into a driveway flanked by huge date palms and arrived at a wrought-iron gate. The high fence enclosing the grounds was spike-tipped, flaked with rust in the sea air. Looking down through the grove, there was Mission Bay laid out vast, the blue-gray swell of the ocean mottled by brownish floating kelp beds undulating faintly on its surface. A fine day for sailing, the sun high and bright, the breeze cool and steady at about eight knots. There were dozens of boats spread out to the horizon, to the south the forest of masts and gray hulls of the Pacific Fleet. A splendid situation for the mansion set among these grounds, which looked like it had been let go for 20 years too many. The date palms were draped with vines, the lawns clotted waist-high. The once white walls were faded and patched by stains of mildew. There were tiles awry and missing everywhere along the roof. The oranges and lemons were dying, choked off, their ornamental concrete planters cracked open and crumbling away, their contents showing dried, tangled roots. Just from outside, the condition of this place made it look worth a million or two less than even a depressed market valuation. It was hard to believe anyone had lived there in a very long while, let alone someone with dozens of millions. Criminal.

The gates were secured by a new chain, though, and a new Yale padlock. I got out and pushed the bell in the post, but it was rusted out. Went back and honked insistently. A door opened somewhere, and two black Alsatians rushed out baying. They came leaping down and hit the gate as if they meant to tear it down to get at us. Yellow-eyed brutes. I stood watching them tear back and forth, slamming themselves into the gate at every pass. Stood on the horn again. A woman's voice from the house called them off, and then a door banged shut on them and it was still. I waited. Finally she came out.

—That should be the Mrs. Joan Hansen, I said, Miss Ewing's companion this past year.

—Is that the person it's gone to?

—In the second will, yes.

She opened her purse and slipped huge black sunglasses over those de Lourdes eyes. The fine pink wool of her suit was muted elegantly by the dazzling San Diego sunlight as she got out of the car. She smoothed her thick chestnut hair and lit a cigarette and held it casually in a way that took effort. I could almost feel how tense she suddenly was.

The woman who approached us down the brick walk and swinging a ring of jangling keys was something else again. Middling height, square and solid. She walked in heavy-soled shoes, black shoes, treading deliberately. She wore shapeless, faded blue Sears Capri slacks, a pink-flowered Sears blouse with a scalloped collar that seemed stretched, too small for those dense shoulders and thick, slabbed breasts. Her skin was a pale, pasty and freckled yellow, and her curly thin light brown hair was hacked off to an inch all over her square head. She had light, reddish brown eyes behind thick glasses with flesh-colored harlequin frames. A small gold watch seemed embedded in the thick fold of skin on her wrist. When she spoke, her voice was bland with a flat Kansas blandness, low and nasal, forced out under pressure. I told her who I was and asked if we might come in and visit the premises. I said Mrs. Falks was a cousin who'd been close to Miss Ewing some years back.

—You're that Conny Ewing woman? she said.

—I'm Mrs. Falks. I've been Mrs. Falks the last 20 years.

—Well, I'm Joan Hansen, she said, unlocking the gate, and I'm happy to know you. Lorna spoke of you.

—She did? How did she, I mean...

—She remembered you sometimes. You used to fool around in Europe when you were in school, right?

—Yes.

—Well, I know about you whatever I need to know.

Mrs. Falks didn't seem happy to have been the subject of Hansen's conversation, but she said nothing. We followed her up. I could see her frowning at the sight of those heavy, rolling, muscled haunches held firm by nothing inside those baggy pants. We entered by a side door, Mrs. Hansen noting, as though blaming someone, that the front door had been locked for years and there was no point to using it now.

That is, we started to enter in. The little foyer was dark, and Hansen marched in ahead of us out of the sunlight without stopping, but I bumped into Mrs. Falks, who'd stopped abruptly and then leaned back stiffly into my arms, her hand held out before her face. She was frozen as though she didn't know whether to brush the sunglasses from her face or defend herself from the musty stench that rose up around us as we stepped forward. Hot, dry, fouled air. The odor was that of a house sealed up who knows how long; the foyer was permeated by rank mildew and dry rot. I almost imagined I saw it coming up out of the cellar like mold and spreading over the walls, rippling like a mossy growth enveloping the dark old mahogany furniture: a mat that would devour it and leave a putrid green powder behind, the residue of itself after it had finished eating itself up, too, and grown dessicated, hard, and crumbled at last away. It was still young and healthy, and almost palpitated into the stale air. Falks' lean arms trembled in my fingers as I grasped them to steady her. Still, she controlled herself and said nothing.

—Come on in! Mrs. Hansen called from somewhere ahead.

We went. The musty velvet drapes were drawn shut on every window. Each room was dark and dreary with dust. The Orientals on the floors were thick with a rancid layer of almost living dust as we stepped on them. Here and there a lamp burned with a dim 25 watts under a tatty, fringed silk shade, raveled with age and cobwebbed. But what most affected Mrs. Falks and tightened her grip my arm as she followed after with me was the crud on the floors: dog food, gnawed bones and rotting chunks of gristle, puddles of piss and dog shit. The place seemed an abandoned kennel. Newspaper had been dropped down on messes of rank vomit or watery shit. Unbelievable! Swatches of hair clung to the chairs or clumped with strings of dust along the moldings.

As we went through the dark rooms, Mrs. Hansen followed silently. She stared at us, her thick arms folded against her hard breasts. Her face remained expressionless, but her pale eyes seemed to sneer with contempt behind those butterfly-winged lenses at Falks' horror, whose hold on my arm grew tighter as she fought to contain herself. I covered her cold hand with mine.

Then we climbed the stairs, feeling our way cautiously on the loose Kirman runner and trying to avoid the refuse. The long, wide hallway was dark, all its rooms shut. At the end there was light reflected under one door, and Falks headed for it. It was the master bedroom. She opened slowly, then threw the door wide. This room was utterly different from the rest of the house: spacious, airy, the old casements opened to the sea. It was freshly-painted, the floor bright with the honey of new wax. There was a king-sized bed made up with a fresh pink coverlet of red-flowered silk, and the curtains were a pink gauzy silk billowing in from the sea wind. Everything seemed new and clean, the rose Chinese carpet glowing with peacocks and pigeons. It was a really lovely room, and there were just enough things in it: an antique vanity and mirror, the sides of the table dressed in pink silk frills with a comb and brush and a crystal atomizer, a few pictures on the walls—good ones, what looked like a Pisarro, a Matisse odalisque, and a Dufy street, two handsome dark Russian icons with gold-hammered frames.

—This is my room, Mrs Hansen said behind us. Do you like it?

—Your room? Falks echoed. And murmured, Where did my cousin sleep?

—She didn't like this place, she always said to me. I think her mother and father must have been here before? She was glad to have me sleep here. I wouldn't at first, but when she said she'd close it up, I thought I might just as well.

—Where did my cousin sleep, Falks repeated.

—It doesn't matter now, Mrs. Hansen replied.

—Oh, does it not? I think it does matter. Where was she kept?

—Well, she stayed upstairs for a while. Across the hall, in her old room, from when she was a girl, she said.

—Where?

We followed into the gloomy hallway and Hansen unlocked the door opposite with a key from that noisy ring. It seemed to me no more than a walk-in closet. Along the wall an army cot, an old iron folding-chair. And that was all. The walls had been papered over with newspaper, front pages from the San Diego Times, and varnished clumsily with mucilage that ran down, congealed like pine gum, cracked and powdering. High up there was a little opening, really only a slatted vent.

—She done it, Hansen said, she done it all herself.

—Lorna slept here? Mrs. Falks said disbelieving.

—A while. Then she got scared to go up and down the stairs, so she moved into her office. That's what she called it, her "office." Oftentimes she wouldn't come out days on end. When she was like that, it was hard taking care of her, believe you me.

—Her office? I said.

—Where she done her accounts and things.

—May we have a look?

We went down. Falk's hand rested on my shoulder, as though she was afraid she'd fall.

—There's nothing to see.

—May we, if you please?

—If you have to.

—I do.

Mrs. Hansen stopped at a door round a corner, beside a hall leading to the kitchen, and fumbled another large key in the lock. But she didn't open it. I stepped round her and turned the knob and threw the door in. An awful smell flooded into the hall. The light seeping through the dirty high windows was dimly green from the overgrown avocados outside. There was a small leather settee in there, split at some of the tufts. There were two pillows covered with filthy carpeting on it, long gray hairs were all over them. On the floor lay an army blanket, still crumpled as if it had been thrown down only yesterday. There were bookcases filled with rotting paperbacks and old magazines, mostly Readers Digest and the Geographic. The floor was covered with newspapers and magazines, dozens of empty gin bottles, all of it thick with dust, and cat shit splattered over it all. Opened fish tins and saucers clotted with more ordure, spilled milk and fish bones and scraps of crudded vomit. Behind me, Connie Falks gasped and ran out. I stepped in further. In the far corner there was an old oak roll-top desk jammed full in every pigeonhole with letters and bills, and there were a dozen old ledgers on it, some opened and turned face down, on them more cat dreck and empty gin bottles strewn every which way. There was a rasping growl, and I saw crouched atop it all in the half-light an enormous, mangy tomcat, his mouth opened as if to bite the air. I stared into those half-blinded eyes as he hissed.

—Jesus! I heard myself shout as the beast's tail whipped about and thumped the desk. He was tucking himself together to leap. My hand flew up and I stepped violently, involuntarily back, slipping on fresh shit, and slammed the door shut on him as he began a crazy yowl. Hansen said nothing. She bent and turned the key in the lock.

—That's where she died, I said.

—That's where she died. What else would you like to see, Mister Lazarus? Satisfied now?

—She was a Catholic, Mrs. Hansen.

—So she said.

—Was there a service for her?

—She had her service. I gave her what she deserved.

—Where?

—You go down the hill to the city, Mr. Lazarus.

—La Jolla?

—Hell, no. She hated La Jolla. You go down the hill and head into San Diego. Know where Old Town is?

—I know.

—Well, you go and ask down there for the Grove Street RC. San Sebastiano, I think it's called.

—You think?

—Slips my mind now. She leered at me in the dark hall.

—Them dago saints sound all the same to me.

You really are something else again, Mrs. Joan Hansen, I said to myself.

—Thank you, Mrs. Hansen, I said, as we stepped out into fresh air again.

—Don't mention it, Mister Lazarus. And goodbye, if we don't see you round here again.

—You may, I said.

Her blank face showed nothing. The weak red light in her eyes stayed on, though.

Mrs. Falks sat in the T-Bird looking down vacantly to one side. She'd laid on fresh makeup and sprayed enough perfume. It was hard to see what she was thinking through those black glasses. There was a wet spot on her skirt where she must have been dabbing at it. Now her hands were clenched in her lap; one crushed a handkerchief, the other twisted her bracelet of fat diamonds this way and that. She said nothing as I turned the car about and headed downhill to San Diego. She said nothing all the way as we threaded the detours where they were always finishing Freeway tie-ins. When I finally located the Church of San Sebastiano tucked at the end of a narrow arroyo, she followed me quietly.

It was cool and light inside, fresh-painted in thick, stuccoed ivory, the tile floor washed, the oak pews polished with lemon oil reeking with incense and flowers from the altar. Two black-garbed crones sat together up front. No one else was there. They turned slyly to see who'd come in and peeped at us, whispering as our heels tapped on the paving. The odors of the church were so strange, coming in from the soft winds mixed with eucalyptus and chaparral and salt the sea sends over San Diego in the dry noon heat. The altar was a dull white marble, newly spread. There were a half-dozen baskets of white and yellow gladioli set before it. Behind, the high reredos was of a vitreous pale blue-white and shiny china that reminded me of bathroom porcelain, though it was ornately molded in a 19th century imitation of the late Spanish flowers and vine-wound curlicues of earlier times. It had that provincial elegance of the garish saloon carvings of recent memory that California still offers tourists. On the walls of the choir facing the nave were new-varnished Mary and San Sebastiano, facing us and blessing, ten feet high and done in the manner of contemporary Vatican postcards, or was it the rotogravure art of the 20s, the Sunday newspaper saints, varnished and looking inanely billboardish, too? The Christ over the altar zoomed towards us awkwardly, stretched concavely to fit the dome and looking somewhat surprised to have been pressed so flat into the thinnest of two dimensions.

We found the priest in the vestry, a young man with a crew cut and horn-rimmed bi-focals. His name was Aloysius Berlind. He was pacing idly, smoking an after-lunch Marlboro. He was flab-cheeked and smelled of cheap talcum. Otherwise he seemed easy enough. Asked him if he knew anything about one Miss Lorna Ramona de Lourdes Ewing. He answered directly in a kind of Baltimore accent that yes, he had in fact officiated her funeral. She'd never been in his cure. Still, he'd been called, and she being after all Catholic, that was one sacrament she needed.

—Called, Father Berlind? When was that?

—Some time ago, he thought, maybe a couple of weeks?

We went to his office to consult the ledger. He had administered the rite... ten days ago, in fact.

—They came by here and pleaded with me, he said. The poor woman had no one and nothing but her Church. Wouldn't I do the office for her? I could hardly refuse, though as I say she's not in my cure at all.

—Who is they, Father?

—Her only friend, she told me. A Mrs. Hansom, was it? Also the funeral director.

—And they took you up to La Jolla?

—La Jolla? Hardly. She was prepared in National City.

—National City! Father Berlind, you went down to National City for a woman who came out of La Jolla! They drove you down to National City?

—No hang-up there. They're both just as far out of my cure, he said.

I looked at him. He was puzzled, I suppose, by my too-evident dismay. He lit another cigarette.

—It was all the same to you, I said, wasn't it!

—Yes, he said. Of course. Mrs. Hansom told me the woman was a poor thing, a waif she'd taken in and made her companion, and that now she was dying. She herself had once been a Presbyterian in Kansas, but now she was Four Square. Anyhow, she knew Miss Ewing was old Spanish Catholic, and Miss Ewing had begged her to look after getting a service for her even if she might have nothing to donate but thanks. I went down there because I was asked. Because it's my duty. It wasn't that far-out.

—Where did you go in National City, if I may ask?

—I patted Falks' hand in mine to keep her still.

—Johnson's. Small place, white frame house with a purple neon in the parlor window you can read two blocks away. You'll find it outside south of National City, where the tracks come in. Johnson's is nondenominational, of course. He gets migrants and vagrants from those shacks you see, and lots of those old pensioners stuck down there by the border. You know that line's like the end of the world for the lost and the poor and the sick. They need a mission there. I thought I might talk to Bishop Furey some time about it. I'd guess Johnson does well enough, though. Probably a contract with the City Fathers of National City. Charity, fixed fees, and such.

—Thank you, Father. One more thing. You saw the deceased. What did she look like to you?

—I hope she was at peace. Of course I prayed she would be.

—Did she say anything to you, I mean outside of confession?

—How could she? She was dead after all.

—What do you mean, Father Berlind!

He drew back in alarm.

—She was already embalmed, that's what I mean. She'd died the day before. Here, look at my book.

—Mrs. Hansen came to you, Father, and took you down to National City because Miss Ewing was dying. That's why you went there, you said. Didn't you say that a minute ago?

—Mrs. Hansom was distraught. She must have been confused by the death of her friend. And then she was taken by remorse because she'd neglected to call the right minister for her—you know these far-out sects, they mean well but they have no sense of the way to do things right. They're always so busy meeting and prying into each other's affairs that when it comes to the behavior necessary in the hours of crisis that come into our lives, they're just lost. Whereas our Mother the Church has 2,000 years of experience to organize and test its procedures for these important moments, don't you agree, Mister Lazarus? I could see Mrs. Hansom meant well, really, because she did come for a real priest in the end, and that's what matters. Don't you agree?

—Father Berlind, I said, you haven't the foggiest notion of what you're talking about. You know that, don't you?

—What did you say? He gagged on the cigarette he was puffing nervously.

—Father, that if there were even one ounce of Solomon's wisdom to be had in the seminaries turning jerks like you loose in America, you'd stop congratulating yourself on your 2,000-year-old organization.

—What?

—I said, Father Berlind, you are simply all crapped up.

I turned to Mrs. Falks and took her by the elbow.

—Let's get out of here.

She held back a moment, staring at me and then at the open-mouthed young boob from Baltimore. She was trying to take in the meaning of my reaction to his stupidity, but she couldn't grasp its implications, not yet. She wavered, then turned round and went back into the church. She stopped to make a hasty genuflection at the altar and went back up the aisle. I followed. At the door, she dipped two fingers in the font and crossed herself, her lips silently moving. Outside, she put the sunglasses on again but said nothing. She knew where we were going to go. Down to the end of this thing, all the way.

We drove the ten miles to National City. The road was crowded as always with the usual heavy shipyard, railroad, and fast truck traffic, and broken-down cars heading to and from Tijuana. The landscape turns abruptly Mexican as you near the border: waterless, treeless, full of scrap and rusting industrial debris, messes of burnt-out car bodies, broken billboards and real estate and roadhouse and Tijuana signs flapping in the hot wind, a dingy, dusty dun wind. Johnson's Mortuary and Funeral Home was as the priest described it: a small, dirty building, the apartment up front hot and padded with dim furniture and carpeting, reeking with the stench of embalming fluid mixed with flowers and candles, a fan rattling in the window. Processing bodies was one good way to make money and stay legal in National City.

Mister Johnson was not home, but the Mrs. Johnson, a short, unhealthily fat little body, was. California Gothic, lizard-skinned, hair in curlers, blue-washed, lank thinning hair. She wore a shapeless orange and red sack dress and walked with a limp on swollen feet in prescription shoes. Arthritic, she remarked, challengingly, had come down from Oregon for the dry air—it was supposed to be good, she guessed. I explained who we were, why we'd come. Did she remember the service, did she recall a Miss Ewing?

—How could I forget her, the poor woman? she said, and what a tragedy that was for her friend.

—What was? I said.

—Her dying right in her arms like that. I say it's what you got to expect from the drink, but people are so unhappy these days I cant criticize them. Mrs. Harmon said...

—Hansen, I told her.

—Nossir, I'm sure it was Harms, Harmon, something like that.

—No, Hansen.

—You sure? Well, anyway, she said they had been down all weekend in Ensenada for the sea air and the beach and to buy some pottery and souvenirs, you know, and the poor thing had eaten something, you know what it's like among them down there. Just go ten miles from here, nothing's safe to drink or eat or even touch, I always say. But it's nice to travel a bit, too, if you can. Her friend, the deceased, I mean, had taken sick, and they were coming home to San Diego, after all it's only 50 miles or so, and they had come on through the border and hardly been five minutes on the road when the poor thing didn't answer her anymore. Passed on right beside her there in the car. So here she was, just around the corner.

—You took a dead person in? Just like that, Mrs Johnson?

—Well, it's our business. Oh, we had the coroner over right away, and he certified the death. What do you think? Mrs. Harms was all broken up by the tragedy, you can just imagine. I took and gave her fresh coffee. But we set her a fair price for the undertaking and the coffin and all. Poor thing, she was just done in by it all.

—That's too bad. You saw the deceased?

—I did. Don't usually, but I did see her. My husband called me downstairs after he finished with putting her together, so to say. She was a lovely girl, wasn't she. Tired looking, and so thin. She was all wasted, Mister, just wasted away. Anything could have took her off, even if it wasn't a Mexican dinner. But Mister Johnson done a good job on her. No one could complain about the job he done on her. Next day she came back and my husband and her went to San Diego for the priest, and I sat with the deceased, which I don't usually do, but I did. When they came back, he did one of those mumbo jumbo services over her, the kind those folks do, though it sounded sort of fine for a change.

—You all did the service here?

—Why, yes, of course. No reason to do anything out there. If the body needs a service, we think it's ever so much decenter doing it in here. That's what we're like. Decent.

—I'm afraid I don't understand you, Mrs. Johnson.

—And then Mrs. Hansen—are you sure that's her name?—she drove the priest back to town, and we sent the body out on the regular schedule.

—Mrs. Johnson, I said loudly enough, what are you trying to tell me!

Through her rimless glasses she looked up at me as if I was shouting nonsense at her. I felt suddenly baffled by her wild chatter.

—What happened to Miss Ewing! I growled at her.

—She was buried. Naturally. We sent her out to be buried.

—But where!

She flushed at me, and glanced sideways at Mrs. Falks.

—I don't like your way of talking, Mister... What did you say your name was? Leezard?

I spoke my name again.

Well, we do honest work here for a fair fee. We're not going to stand for your insults. You come down here from Los Angeles and barge in and ask all sorts of questions. Why don't you say what you really want, Mister Lazards?

—Mrs. Johnson, I said, I am a lawyer. I have a will to execute, Miss Ewing's will, and the estate and its heirs have absolutely the legal right to know where she is. Now will you please inform us?

—She's right where she belongs and nowhere else, and you can't threaten me. I know my business, too. Don't you dare threaten me!

—And just exactly where is that?

—What do you think? Potter's Field.

—Potter's Field! Connie Falks cried out, the first words she'd uttered in hours.

—Well now what do you suppose? People die around here, you don't know where they come from and nobody wants them alive nor neither dead and they come out of these old homes and tin shacks in the desert aound here, or who knows where they come from anyway? But that's sure where they go! she snorted.

—Potter's Field, Connie repeated, dazed. How could you!

—Ma'am, what do you think we can do someone comes knocking us out of bed in the middle of the night with some wretched corpse and drops it on our doorstep? We're honest people, like I said, and we do honest work for a fair fee. Sure, we can do you better on the box for $100 more than we got from her. That Mrs. Harms didn't look like no $100 deal, and Henry never troubled to ask. And even if she might've had it, she might not've paid it over. He could see that. So you can't expect us to take it out of the safe deposit for every stranger drives through National City with a dead body to go ahead and take care of for them. I suppose you think we are in the business of buying plots for our service too? Ma'am you got another guess coming to you.

—Don't you talk to me like that. How dare you!

— And don't you get bossy with us here in National City. You want to find that woman, you go up and look around in Potter's Field, and you can have her, for all I care. We don't make enough on them to waste no more words than necessary.

—Mrs. Johnson, I started to say...

—You just hold on, Mister Leezer or whatever you call yourself back where you came from.

She hobbled to the couch and got a big black and red ledger from under the pillows in one corner, laid it open under the lamp and turned the pages. Here it is, she said, L. R. Ewing: PF #10001-A.Z. 4-13-09. Don't say I wouldn't help you.

I wrote it down and we cleared out.

By then it was four. Drove up to San Diego and parked at City Hall. Took me 20 minutes to find a clerk in the Records Division who could tell me where the County Cemetery was and how to find it. Mrs. Falks was still sitting quietly in the car when I came out. Her face was made up fresh again and in repose behind those glasses. I got in.

—We can go out there now and look for her. Want to try?

She said nothing. She was staring blankly at nothing.

—Or we can have a drink. There's a little Mexican restaurant in the heart of Old Town, quiet patio, olive trees, fireplace. Food's good.

—She seemed to think it over in a stunned way.

—Come on, Mrs. Falks, let's call it a day.

Her head turned to me and the mouth of that handsome drawn face trembled, and smiled.

—You can call me Connie. I'm all right. I'll be all right.

—Shall we have that drink, Connie?

—You're a kind man, Mister Lazarus. I want you to know I think that. Whatever happens now, I know you'll be kind.

I started the car and turned around for Old Town. Poor Colerado Lincoln, I heard my voice saying in my head. Poor Colly. You were right after all.