| Oct/Nov 2015 • Salon |

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Salon |

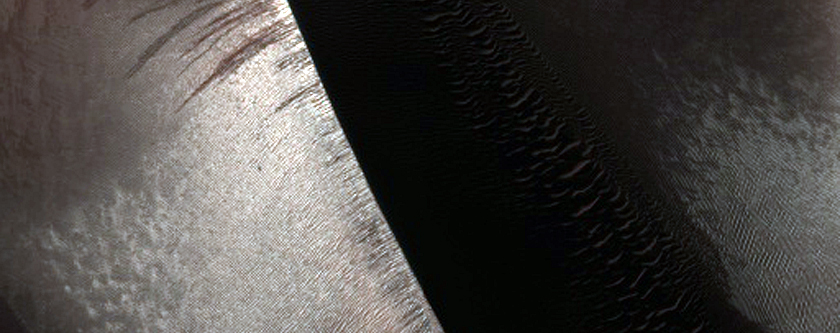

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

A few years back I heard a brief interview on the BBC with the mother of a child who had been sexually abused by a Catholic priest, aired at a time when the church's sexual abuse scandal was at its height. New revelations were occurring almost every day, entire dioceses were going bankrupt as a consequence of having to pay out millions in compensation to victims, some of them now middle-aged. It wasn't unusual to hear the voice on the the air of someone who had been sexually molested by clergy, sometimes many years earlier, and had only just come forward. What was very unusual, indeed unique in my experience, was the response this particular mother gave to the BBC presenter when asked how she felt about what had happened to her son.

She said that, as appalling as the physical abuse was, it was nothing in comparison with the psychological trauma he had suffered as a result of the religious "education" he had suffered at the hands of the church.

These seemed to me strong words, and very brave ones, coming as they were from the parent of someone who had already suffered serious trauma the consequences of which would remain with him for the rest of his life. She could simply have railed against the insensitivity, if not criminal dereliction, of the clergy who were responsible for supervising and punishing the physical abusers. But she chose to speak out forcefully against what she considered the greater crime. Indeed, that was how she put it: She said that if she had to choose between the two experiences—if the boy had to be subjected to one of them—she would have chosen sexual abuse, dreadful as that had been. She said the damage done by the cruel, sadistic religious doctrine was much worse.

My entire education was at the hands of the Catholic clergy, from first grade (I dropped out of kindergarten after the second day, claiming the right to do so because my older brother had just dropped out of his senior year of high school) through college. I was never abused sexually by anyone and never heard of any instance of sexual abuse or any suggestion of such during those 16 years. I was lucky. Questioning of that same older brother in recent years revealed that he had been aware of at least one member of the clergy at the Catholic high school he had briefly attended who was known for groping boys. My sister, at the time very much a Catholic, had withdrawn two sons from a Catholic high school after a similar situation came to light. No doubt other members of my immediate and extended family could provide more instances of a similar kind. My closest encounters with clerical sexual abuse until the tidal wave of revelations that arose in the last couple decades were limited to an Episcopal priest, a married man with a family, dismissed from the local parish for abusing choir boys. Of course, we now know sexual abuse occurs in all religious denominations without exception and probably to the same extent in all of them, making allowances for the degree of control clergy have over the faithful—how insular the group is, how self-segregated it is from the general society as is the case for the stricter, more rigorously observant denominations.

What I was personally exposed to, from an early age and on a daily basis, was a form of psychological terrorism that Chicago mother rightly identified as abuse at least as serious as the physical kind. I cannot address from personal experience what it is like to grow up in the confines of a fundamentalist protestant, Jewish, or Muslim sect, or for that matter a secular cult. But, having heard others speak of their experiences in such situations, I suspect the correspondences are very close to what I endured, human beings being pretty consistent in their behavior and misbehavior throughout place and time. What I can give witness to is my own and, presumably my peers', experience in one particular very large religious organization.

Just a few years ago I heard a Jesuit priest on public radio deny the Church ever held the existence of hell to be a part of its official teaching. Many public figures in the Church to this day insist their religion is one of love and forgiveness, of a merciful God whose Son redeemed by his suffering and death all mankind from the sin into which we are all born. I had eight years of Jesuit education, which meant eight years of religious indoctrination, in addition to eight years earlier teaching by nuns. Never did I hear during that time anyone disavow the existence of hell or the torments therein (though some Jesuits were not above dismissing the nuns as silly females). In my sophomore year of college we were obliged to attend an on-campus three-day religious retreat (I had already attended a couple sleep-away retreats during my high school days) given by a Jesuit who reproduced faithfully the lecture mandated by the Jesuits' founder, Ignatius Loyola, detailing the specific physical circumstances and tortures to be found in hell. You can find an almost word-for-word version of that talk in James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

I was amazed by the man's seeming lack of awareness of what he was doing, the almost exact correspondence of the novel and his talk being delivered some 60 years later—life imitating art imitating life. But in my case the damage had already been done by the priests and nuns of my early youth: all those ad hoc accusations of smacking Jesus in the face as he hung on the cross if we misbehaved in class; endless warnings about and detailed description of hell and its torments; detailed descriptions of the Savior's scourging and other torture; the exquisite sufferings of the Christian martyrs, from being eaten alive by lions to being roasted alive by Roman soldiers. And through it all the insistence on our sinful ingratitude in response to what Jesus had done for us, not to mention what the nuns and priests and our parents were doing for us.

It was mortal sin, and only mortal sin, that condemned us to undying flames. Before we had lost our milk teeth, we became experts at parsing the difference between a mortal and a venial sin, though almost all the mortal sins apart from violations of the Church's rules about attending mass on Sunday and not eating meat on Fridays, were about sex—the most talked about and most undiscussed topic in my formative education. Young children are hardly less sexually aware than are older people. They have sexual feelings from an early age. So, the prohibitions against all sexual activity, from mere thoughts to the most overt behaviors (never themselves described), struck deep and lasted well beyond my youth. Parents, at least parents of the kind I had, were just as prohibitive about sex as was the clergy and even less inclined to discuss the subject. They were, after all, as much in the thrall of the Church as we children were. The nuns' and especially the priests' words were law for them, whatever nonsense came out of those clerical mouths. Paradigmatic of the eight years of psychological abuse we had just endured, at my elementary school commencement the pastor of the parish included in his talk to the graduating class the story of a boy who took pleasure in a wet dream, died and went straight to hell, a homily repeated in other versions throughout my education—teenagers who met with a fatal car crash on their way back from lovers lane, for example. Nobody thought the parable inappropriate to the occasion, or if they did, they never said so.

Critically, anything sexual was an "occasion of sin," mortal sin. You could commit a venial sin by stealing someone's candy bar or a mortal one by stealing a significant sum of money from a poor person. But you could not commit a venial sin by indulging in a sexual fantasy even if you did so during math class with both hands on top of the desk. Any fully willed act against the Sixth Commandment (as Catholics calculate the order of the Decalogue) was by its nature mortal and hence put you in peril of going to hell if you died unshriven.

The clergy's preoccupation with sex now seems inevitable given their mandatory vows of celibacy, and those men and women can seem as much victims of the faith as we were, though it can take some effort to see someone who's robbed you of your childhood and inflicted a lifetime of neurosis on you as a victim him- or herself, merely reproducing the abuse that was inflicted in their own case. But back then those women and men were for me sexual athletes, major-leaguers of self-denial, while I who aspired to be one of them could not keep my selfish eyes off the brassiere ads in my mother's Ladies Home Journal or the tight skirts worn by the shameless public high school girls. My bi-weekly confessions were virtually word-for-word recitations each time of the same formula of "sins against purity," to which the priest in the dark confession box, his eyes carefully averted, issued the same platitudes about praying for strength and, then, praying for him.

I will carry my Catholic terrors with me to my deathbed. You can shed the faith of your youth and free yourself of nostalgia for the comfort of its rituals, but you can never emancipate yourself entirely from the horrors you were subjected to at a time of life when you were still in the process of becoming a human personality. You may as well try to pretend you have never seen men wantonly slaughter other human beings or never experienced the nightmares of a concentration camp. I'm thankful I didn't suffer the former, as one of my brothers did and paid dearly for, or the latter thanks to a pure accident of birth. Nor do I suggest an equivalence between what I went through and what my brother or a victim of the Nazis or the Khmer Rouge endured. Comparing one's suffering with another's is reprehensible, whether it's done by degree or by the number of victims involved. I'm aware I have lived a privileged, indeed protected life such as relatively few people have ever been fortunate enough to experience. But if we are to talk about child abuse at all—and it wasn't so long ago we weren't—we should not stop at the kind that everyone everywhere agrees is despicable. We shouldn't get exercised over the most obvious and egregious ways of damaging a human being, the low-hanging fruit as it were of crimes against children, and not acknowledge the deeply destructive institutional and approved if more subtle ways we wreak the same havoc on young psyches.