| Oct/Nov 2015 • Miscellaneous |

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Miscellaneous |

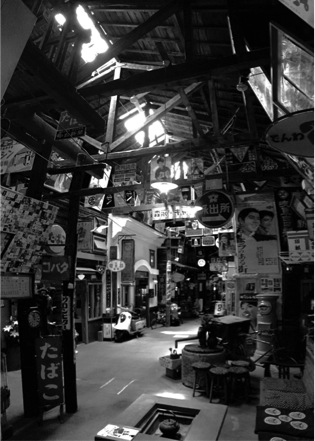

Interior View of the Showa Kan, Takayama, Japan, July 4, 2015

(All photographs by Scott Brennan)

Introduction

Takayama is the gateway to the Northern Alps of Japan. Spared bombing during World War II, the city is renowned for its well-preserved temples, shrines, and traditional wooden houses. Takayama is also the home of the Showa Kan, a museum I visited on July 4, 2015. "Showa" refers to the time period between 1926 and 1989, and "kan" means "hall."

The pieces from the permanent collection on display during my visit emphasized the decades after World War II (roughly 1950 - 1980) when consumerism flourished in Japan in the wake of the post-war malaise. The museum's everyday objects and kitsch—now technologically and culturally obsolete—are poignant in the way their presence in society has so rapidly faded. The museum thus encourages nostalgia, and in reframing the context of the objects (they are not in a home, not for sale at a flea market, not on a trash heap—they are in a museum), we become aware of how quickly products and cultural reference points evolve and are replaced, even within the span of a single generation. Thus, the museum gathers significance in that it shows us the context of our own lives placed not within the more abstract context of past millennia, but within (or, perhaps more interestingly, just outside of) the specific brackets of our own timeline. The objects in the collection—most of which were commonplace in the developed world during the latter half of the Showa period—consequently (and surprisingly) take on the aesthetic value of art objects. This photo essay examines six objects on display within the museum.

This partially mechanized alien robot manufactured in the 1970s greeted me outside the Showa Kan. It boasted a functioning mechanical arm and a rotating head driven by an electric motor. I was puzzled by the robot because I could not fathom its original purpose. What company (or individual) would fabricate it, and why? When and where was it in use? Without context, I had no way of knowing. Still, I did appreciate its universally recognizable alien features—the oversized head suggestive of superior intelligence and the enormous, insect-like eyes that brought to mind a hive mentality supposedly typical of certain extraterrestrial races. This battered robot—with chipped paint and dents and dings here and there—embodied my fading familiarity with the decade in which it was produced. It made me think about how the not-so-distant past becomes as alien to us as our own future is, and thus the robot's silly, almost mocking aspect consoled me as I began my tour of the museum.

Godzilla is, of course, one of the great icons of popular culture, a gift from Japan to the world. What struck me most about this early iteration of the toy was its level of detail—especially the scales, the facial features, the teeth, and the well-defined musculature. How old was this particular Godzilla? Twenty, thirty years old? Though Godzilla still menaces us today (contemporary movie sequels are made from time to time, Godzilla toys are still manufactured), this beast seemed a relic from another age. Its designer is likely deceased, the durable, relatively expensive rubber material no longer used, the machines that produced it retired. Oddly, the figure caused me to think about religious iconography, like the image of Christ's crucifixion, for instance; how the ubiquitous images produced in, say, the Byzantine period differ from the images of the crucifixion painted during the Renaissance, and how those images, in turn, differ from the iconography produced in our age—yet they are all still common in that they are images of the crucifixion. I had a similar sense of difference and similarity looking at this Godzilla figure. It was unquestionably familiar to me while simultaneously dated, even though it was certainly manufactured during my own lifetime.

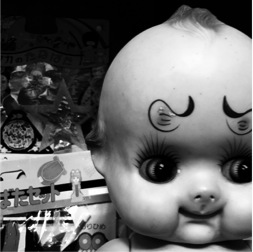

Are kewpie dolls supposed to be cute? The original dolls were based upon a comic strip by artist and writer Rose O'Neill, and mass production of them began in Germany in 1912. Kewpies became wildly popular in the early 20th century as companies like Effanbee and Jesco created hard plastic versions of them. Now, it seems, much of that popularity has faded and we are left with these nude, orphaned, genderless, caucasian dolls—a dorsal of hair on the top of the head, the oversized eyes with exaggerated eyelashes (as if painted with mascara), the severely dilated pupils, the undersized, bridgeless nose, the nostrils highlighted with gold paint, and cheeks which threaten to engulf a tiny, grinning mouth. This particular doll sports a sort of stylized tattooing over the faint circular eyebrows, a troubling, inexplicable adornment perhaps intended to make the kewpie stand out amongst its peers. What may have once been cute and desirable in another era has become a mildly disturbing collectible in our own. And what of the original comic strip that inspired the doll? In what archive does it persist, and does anybody ever read it?

This severely cropped photo provides enough information for us to identify what it is—a radio. The mechanical dial used to control the volume, the standard technology of a bygone era, is still in use today, even though newer, digital technology for years has been capable of completely replacing it. Why do we continue to use old technology when newer, less expensive technology is available to us? Why do some overlapping technologies persist while others do not? Is there greater utilitarian and aesthetic value in a physical dial, and does that value cause it to be retained? Does the mechanical dial communicate its purpose more effectively than, say, the touchscreen? And when does a battered old radio like this one change from something that should be thrown away or recycled into something people feel should be preserved?

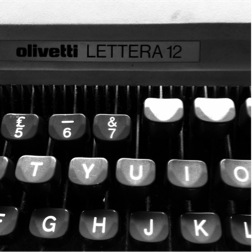

The Olivetti Lettera 12 was manufactured in 1979. A featherweight, its body was made of cast-injected ABS polymer casing, the lightest and cheapest of all Olivetti typewriters, which was a true disadvantage because it did not have a solid mechanism or a stable typing action as a result. Additionally, the 12 did not use a standard ribbon spool but rather a proprietary cartridge-type ribbon, so replacement was a problem. With its streamlined, space-age appearance, it proved to be one of the coolest looking pieces of 1970s junk ever to despoil the typosphere. Now, though, what does the 12 represent? How many processes and procedures have also gone by the wayside, products supporting modes of work that were once so prominent in daily life now almost entirely forgotten? How many people who purchased and used the Olivetti Lettera 12 are still alive and would be willing to comment on their experiences typing with it?

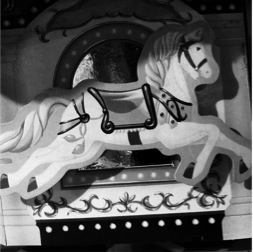

Cardboard toys don't last long, but this beautiful tabletop carousel has. Wind it up and it begins to spin, the foil mirrors reflecting the light in the room while the horses driven by a simple system of gears gallop up and down while music in the internal music box plays. Still, for how long would this carousel actually amuse a child? As interesting as it is, not very long I think. Which begs the question, was the cardboard carousel really intended to be a child's toy? If not, for whom was it intended? Additionally, what kind of manufacturer would invest the time and resources, believing such a product would be profitable? And which stores carried the carousel, hoping it might sell? Or was it simply an inexpensive-to-produce amusement the manufacturer, the middleman, the retailer, and the consumer could appreciate—an ephemeral object not really meant to last, but somehow has?