Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

Flat 61c—Tanna Kolvea

The steps leading up to Tanna's sixth-story flat hawed and hemmed. Six flights, 12 steps each. When the other tenants were about, the house was a babel of 12-tone rows, but today Tanna's footfalls sawed and moaned an ascending series alone. Alone. Finally. She enjoyed her own company, which she had so much more of now that she'd finally got rid of Fred.

Needy Fred: the lumbering, hairy galoot who loved Tanna with every bit of his lumbering, hairy heart. To say Fred had fawned on Tanna would be mildly underestimating the stretch of his devotion. He'd lavished Tanna with all manner of gift, from the daily necessities of, well, food, to life's little luxuries: prettily scented soaps, pralines, and poems. Oral epic poetry he performed for hours until Tanna—and sometimes Fred himself—fell asleep. This situation had gone on for so long, Tanna wondered, as she squeaked and squawked up these infernal stairs, if it hadn't always been this way, if it really was over, if anything epic once begun ever ended.

At the sixth floor, she gripped the banister, pulled herself up to the landing, and ran headlong into it: an enormous potted tree, head bent like a giant in a pillbox. Or, with its broad red ribbon round its belly, a deciduous genie. Or was it an evergreen? Some sort of pine? Maybe a banyan?

There was a note. And it had her name on it—Miss Tanna Kolvea—in large loopy letters. Inside it read, "My hard-bitten Miss Tanna Kolvea. Our parting has germinated and sprouted within me like a seed into a sapling, and here is the sorrow it has become. Remember me, Miss Tanna Kolvea, and my massive sorrow." Tanna rolled her eyes. Fred had such a wordy way with words.

"Goodness," she said and smiled at Fred's massive sorrow. Sorrow was almost always ironic in its grandeur and spleen: it was so green; it blossomed and thrived. "So vital," Tanna said. "And kind of sexy." But where was she going to put it? Not in the flat. Fred's sorrow needed more headroom than she'd ever be able to provide it.

The roof terrace would be an excellent place. It wasn't far, and Fred's massive sorrow could grow up to the stars if it had a mind. Tanna turned her attention to the last flight of 12 steps up to the roof terrace. She'd need help. Fred's sorrow looked as if it weighed a ton. There were the two sweet, burly men who lived together on the first floor and did odd jobs around the building. They'd help if she made a rhubarb pie. She'd made one once, and Bernie, the smaller burly man, said he'd have climbed mountains for a fork of it. "Well, let's just see about that," Tanna said, moaning and creaking back down six flights of stairs.

Later that afternoon, Fred's massive sorrow sat comfortably on the roof terrace while two sweet, burly men feasted on a pie so tart yet so sweet Bernie would have carried Fred's sorrow to the moon if that's what Tanna had required—which, in hindsight, would have been a much better place for it.

In a rusting lawn chair, Tanna sat next to the tree and watched it grow. Alone in the last few hours, it had produced cones and dropped them, buds and dropped them, blossoms and dropped them. It was already a foot taller, and the pot had begun to bulge as if the roots were seeking sustenance.

"I'm not going to water you, if that's what you're thinking," Tanna said to the tree. "That's not how break-ups work, you know. One doesn't cultivate the other's sorrow. I mean, really," she said and left the tree to sort out its mess of grief, which was deepening by the second.

The Roof Terrace

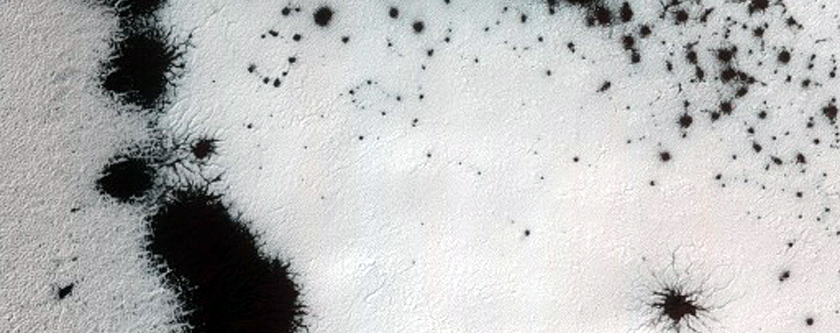

One could hardly say Fred's massive sorrow was happy on the roof terrace, but it did thrive. It went through the four seasons—football, rabbit hunting, beach and opera—in one day, every day. Its cones, catkins and seeds sprung out and tumbled over the edge of the grand six-story building and onto the ground below. Each day at noon it blew billows and billows of jaundiced pollen, then at four its opera-season coat of brittle brown needles. At six o'clock every evening, the songbirds who had nested in its boughs in the a.m. dropped dead, rolled off the roof and dappled the ground below with cheery pinks, greens, and blues. A spectacle. A show. A miracle—albeit a rather morose one.

"Pretty!" the tenants agreed.

The tree at first peeked demurely from the roof's edge. Passersby would remark upon the novelty of a tree—was it an oak, a spruce, a banyan?—perched up there all alone. But as the years ticked off, Fred's massive sorrow became true to its name: a shadow over the building, purging all manner of mess around it, infusing the neighborhood with the sweet smell of decay.

"Like presents, the birds," some tenants remarked. "Like when a cat brings you a mouse."

"Hogwash," said others.

"We should get rid of the tree," one of the tenants suggested.

"Who'll pay for the removal?" another asked, and before anyone could answer: "Not I."

"The tree will be the end of us. We'll be buried alive in rot and dead robins."

"The end," someone said, "will be the end of us. And the end will surely come. As it always has."

"Hogwash."

"Fine points."

"Hear, hear!"

So that was that. It was decided the end would be the end of them, and there was nothing they could do about that, so why waste money on tree removal when they could spend it on, say, the opera? Or food?

It was not long until the first floor became known as the cellar. The tenants still lived there; they simply weren't at street level any longer. They were anxious and scuttling creatures, like moles or badgers or—

"It's cozy down here," someone of indiscernible gender said, leaning briefly out of its dank recess.

But up on the roof terrace, it was not so gemütlich. Exposed to the elements, Fred's massive sorrow grew stern. Defiant, proud, erect—all the qualities, in fact, of a tall and somber thing. Like a tree. Which it was.

Yet as it grew toward the stars, its roots were starting to press against the terracotta pot like eager children, fingers and noses squashed against car windows, leaving home for the last time. Hairline cracks spread across its bottom until a tiny capillary poked through and plunged through the pitch toward flat 61c. Sorrow knew its way.

Flat 52a—The Jollys

The Jollys first noticed the damage when they arrived home, sunburnt and two kilos heavier, from their three-week all-inclusive holiday in Barbados. A corner near the ceiling in the living room was plumper, as if an arm were pressing against the drywall. Or something like a pipe or—

"—a root?" Mrs Jolly ventured, gawping up at the corner. She was still holding her suitcase in one hand, her three-year-old's arm and a sombrero in the other.

She called Bernie, the sweet and burly superintendent, who also gawped up at the corner awhile before deciding it had always been there.

"Always been there," he said.

Mr Jolly, gawping now, too, started to disagree but got a swift elbow from his wife. "Ah, yes," he said. "Always been there—long before we moved in, I'm sure. It's a pipe."

His wife smiled, nodded. "Yessiree: a pipe."

The pipe grew and eventually branched out into smaller, hairy pipes, which grew and branched out into yet smaller, hairier pipes—which was all quite unpipelike. Though the walls were beginning to crumble in places, there was no way in hell the Jollys were going to pay for repairs. They kept referring to the roots as pipes for years after it was obvious the roots were roots.

"They're harmless, the pipes," Mrs Jolly said, because no one had suggested to her the roots might curl around her or her son, Zak, in the night as they slept. No one had mentioned the whispering, so wordy and love starved, coming from the walls. No one had conjectured there might be a sinister life force in these hairy, supernal fingers springing up here and there—and then suddenly here. But then the family hadn't been strangled in their beds, had they? Well, not yet.

Years passed as years have always done, and the Jollys forgot they'd ever had anything but rustic, hirsute panelling. The flat was dark yet so cozy. They hooked crystal Christmas ornaments on the curtains of aerial roots hanging down from the ceiling in the living room and sang "Deck the Pipes" as they decked them. If they'd ever known anything different, they certainly didn't know they knew.

Zak, the then three-year-old, was now 13 and a dark little creature of indiscernible gender. It listened to contemporary German opera, John Cage, and Pink and rarely left its room. It talked—but of course mostly listened—to the wordy walls in its sleep and scraped faces into its skin with the jagged tip of a perfectly straightened paperclip. Of bats. Of skulls. And the bugs who tunnelled through the walls.

Flat 26c—Justice and His Grandmother

When Justice brought home finger-painted art of his family, there were only two figures squidged in bright green and pink: a small boy and a bug. A soldier termite.

Sadly, Justice didn't have the talent to draw an anatomically correct soldier termite or the English language skills to describe her, so his teacher assumed the child's grandmother was merely, yet monstrously, bottom-heavy with an odd hair-do. And Justice wasn't actually aware his grandmother was a soldier termite. But she was.

She hadn't always been a bug. When she was a little girl in Dortmund, she was a little girl. But then the vagaries of age and worry—and Justice—shrank her. By the age of 40, she'd become pretty much the soldier termite she was now.

Justice was supposed to have been called Justin, but in the hours following Justice's violent birth, his mother had lacked the energy to spell neatly. Then shortly thereafter she'd lacked the energy to live—and that's why Justice lived in the tiny guest bedroom with his German grandmother, the soldier termite. At first she spoke German to Justice, but as she shrunk she also began to click, more and more, until the only thing left of her German was a guttural rasp and a bit of a rolled R.

The grandmother catered to her grandson's every need with super-soldier termite strength and a mandible-to-the-wheel sort of determination. Her whole life was Justice. She stood guard over him when he slept, nibbled dead skin cells from his nose, and six-leg tickled him under his knees in the evenings. She gave him a mud mask on Sundays and made him a tasty mush each morning from the roots growing down through the walls; it was of course regurgitated, but what he didn't know wouldn't hurt him. Her bedtime stories, clicked with waving, flailing and pumping legs, were epic. They transported Justice to a world where boys were encouraged to nestle down deep into themselves, to a world rising or sinking depending on how one looked at it—to a world, in fact, very much, if not exactly, like his own.

His window was boarded up of course, had been for decades, maybe forever. The first and second floors used to be above ground. At least that was the legend. Justice lived in a magical place. A changing place. A massively sad place. Which he found fascinating.

"Sinken wir, oder werden wir begrabben?" he asked his grandmother, who clicked that it didn't much matter if they were sinking or being buried, did it. The effect was the same.

"Na ja," he said. "Wäre aber schön zu wissen."

Click, click.

"Schon gut," Justice said, brought his bowl to the sink and rinsed the woody residue of root mush from its rim. He faked the ambivalent deadpan he knew his grandmother so needed to see, but inside he boiled with wonder and empathy for the sinister viral spirit spidering through the house.

Flat 61c—Alacia and Stephin Dornstown, 1901

Alacia and Stephin considered themselves lucky beyond words. The building on the corner was the newest, the swankest place to live in town, and they'd gotten a flat. South-facing. Never mind they'd borrowed the first year's rent from Stephin's parents and lied about their jobs—Stephin was not a lawyer and, despite her odd name, Alacia was not a famous actress from Portugal. They were in! In! In! In! In the first high-rise building to be built in Dornstown in this new, grand century.

But as it turned out, they weren't the first, and Alacia despised not being first. She would have loved to enjoy the supremacy of firstness; she always had. She could have welcomed subsequent tenants into her home—her building—but now she was forced to grin and accept welcomes from speedier tenants with their supreme smiles and firstly bunt cakes, the traditional confection of welcome. Alacia despised bunt cake: the name didn't really say what was in the cake, like a chocolate, coconut or caramel cake would. What is bunt?

"Thanks!" She grinned down at the bunt—whatever—cake. Really, there could be anything in that cake. Gravel. Kangaroos. Sorrow. Nuts. She despised nuts.

"Vee are having a séance today evening on ze rrrroof!" Wren from 44b was still holding out the bunt cake. She was a stout, German woman who wore large floral patterns because she thought they made her look happier.

"A séance?" Alacia said.

"Ze most famous mentalist of our time vill be zere." Wren sounded like a brochure with a strong Teutonic accent. "She has promised to schpeak to ze departed."

"Goodness."

"You vill come." This was not a question.

In the end, Alacia and Stephin went because neither one had ever been to a séance. They took their seats at the large, round table set up for the performance and introduced themselves. They were Alacia and Stephin, obviously, and the other tenants at the table had names as well.

"The table is round!" the mentalist began. She was an elderly, black-turbaned woman who swooned a lot and whose chin was stuck at a 100-degree angle as if to embody her levitating force. "And therefore it has no corners." She panned the tenants as if to invite praise for this revelation.

"Even I knew that," whispered Alacia. She despised the obvious.

"Silence!" The mentalist swooned, stretched her arms across the table, and spread her palms toward the darkening sky. "I will now summon the departed."

"Aren't we meant to join hands or something?" Stephin asked.

"And close our eyes," Alacia added, "so you can pull some rabbit or thingy out of your what's-it?"

"Hogwash."

"Silence!"

"Not very séancelike," Stephin whispered—Stephin who'd never been to a séance before.

"I am beginning to feel an energy. A presence. A massive one. Some massive sorrow," said the mentalist. "Somebody's very, very put out."

Stephin and Alacia looked around. They didn't really care much for the word sad. They were keener on swank, lucky, supreme, supernal—all that stuff. They were in the newest building in town in a new century. Sorrow belonged blocks and blocks away.

"It's emanating from that corner." The mentalist rose slowly—Alacia gasped, thinking at first the mentalist was levitating—and crept over to the edge of the roof. "Here. Here! A massive sorrow. Clearly massive."

"But there's nothing there," Alacia whispered.

"Well of course there's nothing here," the mentalist said, a wee bit out of character. "That's why we call them the departed, you mule."

"Goodness," said Alacia.

Stephin sniggered. He hadn't married Alacia for her smarts.

"Its name is Fred." The mentalist swooned back into character. "Fred!" she called out. "Speak to me! Speak." She threw back her head and screeched. "Speak!"

"Goodness." Alacia despised this woman and this Fred, who was obviously not very swank.

"Fred is sad," said the mentalist. "Wait. Fred... is what? You're not the departed, but the not-yet-arrived? Ladies and gents, Fred is from the future. What? He's come to warn us, well, you that is. I live in Leicester. Shhh!"

"We didn't say anything," said Stephin.

"Fred says your great grandchildren will be buried in his sorrow. Buried alive!"

"Well, that doesn't sound too bad," said Alacia. "We might not even have children, and even if we did, they'd probably be living in America by then. Or Portugal. What year is this boring Fred person from?" Alacia asked.

But no one was listening. The other tenants, who were not so ambivalent, worldly, or child-averse, were leaving. There was pandemonium, or at least as much pandemonium as could be wreaked by six upper-middle-class tenants on a roof terrace. No one jumped over the edge. No one cursed. No one forgot his coat.

But the middle-aged couple from 31d vacated their flat before the week was out, forfeiting almost a month's rent. The remaining tenants agreed to never speak of the séance again, to never ever speak of Fred's (potentially) massive sorrow.

Flat 61c—Tanna Kolvea

The building survived the world's wars; but in the years following, mounds of debris—rubble, appliances and the corpses of those who hadn't fared so well in the wars—lingered, mostly in black and white documentaries shown in America and Portugal.

"A true survivor," noted a passerby.

"A gem," one of the tenants remarked when it became apparent the owner of the building had died in the bombings, leaving the building—the only one left standing in Dornstown—to the tenants in his will. Life, although surrounded by heaps and heaps of debris and dead people, was good.

Until one day, rather suddenly or gradually depending on how one looked at it, the town was bright and pretty again in pastel greens and pinks. Dornstown was so bright and pretty in fact, hardly anyone—if anyone at all—noticed it had ever been anything but. The children, never having known the pangs of war, thought the town had always been a quaint hamlet graced with 20-year-old three-story villas and the occasional bungalow (since these were the dernier cri in California, and the people of Dornstown were enamoured of California's pink-and-greenness from San Diego to Yosemite).

On the square, statues—of men on horses, of men wielding guns, of men waving flags, of men on horses waving guns, flags in teeth—were fables and myth, frozen in time. Life was simply too still and manly to be anything else than what it was: stunned, like a photograph, for decades.

On the stateliest corner in Dornstown, the building sat and sat in this glass-calm sea of oblivion until one day a little girl was born into the inherited stately squalor of her great grandmother's home, flat 61c—a girl named Tanna Kolvea with a face and heart of granite. Her violent birth split her poor mother right down the middle but woke the world from its post-war depression. She was so pretty, the tenants agreed. She'd break hearts. Well, at least one.

Flat 52a—The Jollys

Elmar Jolly was born into the world a tiny gem who could see angels, yet by the age of six his disposition had darkened. He still saw angels, but now they agitated him. They kept him awake, orating epic poetry.

At night the needy walls wrapped around him and tried to cuddle. They whispered they empathized with Elmar's sensitive nature, they wished him serenity, they wished him success, they wished his named weren't Elmar. "Such an ugly name," the walls whispered. Elmar's parents had given their only child the name Elmar, never thinking for a moment they'd actually use it. No sooner had Elmar popped out than they started calling him Zak.

"Also ugly. So ugly."

The walls called ElmarZak Angel, a logical choice. They talked to him about the woman known as Tanna, how she'd crushed the heart of a man named Fred, how Fred's sorrow had grown from a seed into a tree, probably a banyan. The walls taught the little boy about sorrow and the pandemonium it causes, an enervating, spreading, sprouting pandemonium.

But as he grew, he began to listen more closely, to understand. Sorrow was no light fare. Sorrow turned one inwards, deep down into the depths of oneself, where confusion is cozy, freeing, and Germanic.

At 13, Angel spent most of its time listening to atonal symphonies and drawing pictures of hairy oblong creatures it called Freds, which it showed to no one, especially not its parents.

The Jollys were the type of people—the type of tenants—who cheerfully refused to do anything about anything. Everything, from the stove to the toilet seat, was broken in the flat, but Mr and Mrs Jolly would do nothing about it.

"It's always been that way," Mrs Jolly would say.

"Yep," Mr Jolly would confirm. "Always been that way."

But Angel knew better. Angel knew things were changing all around. In spring, the walls sprouted little blue flowers, and regardless of what the rest of the tenants said, the ground outside this building was heaping up around it. It was easy for Angel's parents to deny this: they lived on the fifth floor. When Mrs Jolly's bridge club would ask why the fourth floor was on street level, she'd simply smile and say, "It's always been that way."

But it hadn't. Angel remembered distinctly leaving the building once on the second floor. Or was it the fourth? Angel hadn't left its room in so long and for good reason: Angel's parents, with their cloying smiles and doe eyes, were out there on the other side of its door. They were always there. Smiling.

"One day," the walls whispered to Angel, "you'll have to leave. You know that, right?"

"I know."

"You're different," the walls said. "You understand sorrow."

Angel knew this but didn't answer. Different could be good or bad, and Angel never knew the difference. Angel was confused: the sudden seemed so gradual, change so permanent, and depth was hardly distinguishable from height. Nothing meant anything one wanted it to mean.

"You're special," said the walls, "You see how intricate and enervating the effluents of sorrow are."

Angel nodded but also thought the walls were a bit verbose. If a word wasn't used in a contemporary German opera, Angel probably didn't know it. It knew it'd have to leave the building, though. Often, it dreamt of living in a flat alone, or maybe with a man or a woman. Of living somewhere else, like America or Portugal. Of living, generally.

"Zak?" Angel's mother was at the door.

Angel rubbed a finger over the rough, hairy door frame, stood there in silence. If it didn't answer, its mother would think it was asleep or dead or had never lived, which it hadn't really.

Flat 12b—Tanna Kolvea

Tanna had to get out. Everyone said her imagination was running away with her. Roots didn't curl around sleeping tenants and cradle them, someone said, although Tanna had never used the words curl and cradle. "Ridiculous, you stupid cow!" they said in a curiously affectionate tone. "Roots don't possess telic sensibilities to seek out—"

"Yes they do!" Tanna would cry. "That's exactly what roots do. They press through mountains to find sustenance! Through bedrock!" Tanna was quite hysterical, hadn't slept in months.

"You could have the tree removed," someone suggested, which at first seemed an excellent idea.

"You could apologize to poor Fred," someone else said, which was way down low on Tanna's list of ways to solve this problem.

So she made rhubarb pie and invited the assistance of Carl and Bernie, the sweet, burly superintendents from 12a. Yet after surveying the scene—the root system was so intricate and remarkably strong (in a word, massive), chopping down the tree at the base of its trunk would hardly guarantee success—Carl and Bernie, both vegetarians and members of several tree-hugging associations, decided against any chopping.

"It's too massive," Bernie said, cheeks bulging with pie. "It'd crush the building when it fell."

"True," said Carl, cheeks equally bulging. "And this building is all we've ever had."

Tanna told the other tenants she was living in 12b only temporarily until she found a flat in another country. She'd done the maths. Wellington, New Zealand, was the furthest city from Fred's massive sorrow. The only thing keeping her from realizing this plan was abject poverty. Tanna was penniless. She'd inherited the right to live in the building rent-free in any space that came available from her great grandfather Stephin Kolvea, the divorcée who'd reportedly been married to a very ill-tempered Portuguese actress.

Living next door to Carl and Bernie relieved some of her fears. They assured her Fred's massive sorrow would take years to burrow through the house. The roots were still knocking about the third floor.

"Hmmm," said Bernie.

"What? What?" Tanna was hysterical.

"Twenty-six c has reported protruding pipes," he said, "but I think they said they'd always been there."

"And they're Irish," added Carl.

Tanna caulked every corner and seam of her flat, every crack and cranny, every thing. She'd read about the impenetrability of silicone and hoped it was at least less susceptible to sorrow than bedrock.

Flat 16c—Justice and His Grandmother

Justice's grandmother used to talk about the old country; now she only clicked about it. The old country was a place called Germany where they spoke the language she used to speak. The old country was full of beerhalls with wooden tables reeking of stale beer and blood sausage: "A homey, quiet place," she'd click in German with a swoon of nostalgia for an era when she wasn't 4,000 times too small to wear a dirndl. Even without the dirndl, she'd return in a second if she hadn't inherited this flat from her Auntie Wren, legendarily a large woman who'd thrown wobbly fits about some impending sorrow whenever she was lent an ear.

Auntie Wren had been the family nutter, the huge, exotic aunt who lived in the foreign country. Then the bombs fell. When the dust settled on the detritus of war, she became the quite attractive nutter with the free flat in the only building still standing in the foreign country. So one thing led to another, as things have always done since things began leading to other things—in this case Justice, who was having trouble at school.

Justice didn't speak English. He clicked. And when that went un-understood (which was pretty much always), he spoke German (which was not much better). This went on for several more years than it should have, until on the first day of sixth form, Justice was sent home with a note neither he nor his grandmother could read but which, his grandmother clicked, tasted very nice. Recycled paper was so tender, blue ink so sweet.

The next day Justice was sent home again with a similar note, and the next and the next, until Justice's grandmother, feeling a bit bloated and dizzy from all the ink, finally got the message. She could teach her grandson better than anyone anyway. She was excited by the new project. First subject: mud shelter tubes!

Flat 12a—Carl and Bernie

Bernie lit another candle. Cozy cost a lot in wax and matches. He sat in his den—at four floors underground, he had nothing but dens—and read Proust by candlelight. In French. He didn't understand French, so it didn't much matter the light was too dim and Bernie's eyes too weak. At 96 he only pretended to read anyway.

Carl, Bernie's partner of way too many decades, was in the kitchenden cooking a root vegetable soup (unrelated but possibly subliminally suggested by the roots peeking through their ceiling). Carl was adding garlic and paprika to the pot because he knew they gave Bernie indigestion.

"It won't be long now," said Bernie.

"Oh, no, the soup'll need another 30 minutes at least," Carl shouted, squashed another garlic clove and scraped it into the soup.

"Confound it. I mean till the roots reach soil. Real soil! Confound it! And that'll be the end of it. Of her."

"Fred's sorrow ain't dumb," said Carl, standing at the door to the diningden.

"Wonder why she didn't just say she was sorry," said Bernie. "Could've saved everyone a lot of grief. Get it?"

"Ha. Good one."

"It'll all be over soon," said Bernie. Although too deaf to hear the roar of termites in the wall, he was nonetheless more than correct in his prediction.

"It'll find her, and when it does..." Carl rubbed his hands together and grinned.

"I suppose you're right. May she rest in peace—until then of course."

They laughed heartily. They both thought Tanna had been a pain. Her last wish had been for Bernie and Carl to bury her beneath silicone-slathered bedrock in New Zealand, and she'd stockpiled enough rhubarb pie in the freezer to pay for the trouble. But when she died her unremarkable death, Bernie and Carl schlepped her body to the third cellar—the farthest from the building as they, at 96, were prepared to drag a corpse—and bricked Tanna's rigid corpus into the crawlspace. There was something literary about this, but since neither Carl nor Bernie enjoyed literature, they were oblivious to any allusion this might call to mind. They simply wanted to be done with the woman. It was her fault, after all, the building was sinking, becoming a six-story, termite-infested hill with a single, massive tree at its top. If she hadn't handled poor Fred so shamelessly, Bernie and Carl wouldn't have had so many dens. It was that simple. Still, they enjoyed the pies.

"And when it finds her?" asked Bernie.

"Dear Old Fred's massive sorrow?" Carl shook a big, red cloud of paprika into the soup. "It won't be pretty. It'll scratch and bore into her with its jagged, woody fingers and lick up her cells, it will. It'll lap all the juicy bits and gnaw on the hard ones—and you know there were many hard ones—till its sorrow is plump and sated. Soup's ready!"

Flat 16c—Justice and His Grandmother

Justice hadn't meant to kill his soldier termite grandmother. In hindsight, it probably had not been the best habit for her to sleep nestled in her grandson's left armpit. Cozy, but rather unsafe. In hindsight.

Justice had crushed her. And now he was faced with the task of burying her, if one buried termites. Burying a subterranean termite seemed a tad redundant. He didn't know, but it didn't matter, because before he could finish Googling the topic, he lost her.

Reality hit him that evening as a stabbing pain in his stomach. Without his grandmother to regurgitate mush from the wood of the old house and the roots networking through it, what would he eat? And how would he rear himself? Being only forty?

He nibbled on one of the smaller roots protruding from the walls in the kitchen, but it just wasn't the same. Not like grandmother's mush.

He'd heard once from the walls there was another boy living on the fifth floor. His name was Zak or Elmar or some other ugly name. If anyone knew what boys ate, ZakElmar would. It was worth a shot.

Four 12-step flights of stairs was a bit much for a boy who hadn't been out of his flat in 20 years. Justice was still catching his breath when Mr Jolly came to the door.

"My, my," Mr Jolly said. "You're a hairy one."

Justice had not seen himself in a mirror since he was a young boy, but he assumed this was a compliment. "Thank you, kind sir," he clicked.

"Excuse me?" Mr Jolly smiled.

"I've heard there's a boy here named ZakElmar or something ugly like that," Justice clicked, trying to click politely like his grandmother had taught him.

"Huh? Boy, you're clicking like a bug. Can't you speak English?" Though this sounded impolite, the stupid grin on Mr Jolly's face said otherwise.

Justice stared at the man and cocked his head to one side. Of course he was clicking. Didn't this creature understand clicking? Maybe German?

"Ist ElmarZak zuhause? Ich suche einen Freund," Justice said. "Ich hab Hunger."

"That's not much better." Mr Jolly's grin grew and grew.

"Who's at the door?" Mrs Jolly's grin appeared behind Mr Jolly's.

But then another creature, naked and slight, appeared behind Mr and Mrs Jolly. Like an angel, his hairless body was scrawled in myth.

"Ich bin da," Angel clicked.

"Ich freue mich," Justice clicked back. He was so hungry.

The Crawlspace

The space Bernie and Carl had provided Tanna was not much larger than a coffin. So little air was let in—so skilful was their masonry—the degeneration of Tanna's body was achingly slow, as if it were delaying its inevitable end—something which can hardly be substantiated or refuted. After all, she was well holed up: anything could be true behind all that brick and silicone.

So perhaps this is: Miss Tanna Kolvea had never been anything more than the sum of her bits and cells and bacteria—in their zillions, each a loveless and thankless little creature of indiscernible gender. All they needed to thrive was a bit of oxygen, yet thriving was not happiness. Tanna had never needed happiness. And now oxygen was the last thing she needed.

The crumbling began in a corner and progressed downward until a root not larger than a galoot's hair poked its way through into Tanna's chamber. This happened slowly or quickly depending on how one looked at it, but it happened as all things do. The hair drooped more than dropped toward the corpse—so sad was the little fellow. Perhaps a tear or two fell. Then with the force of the world's mightiest, meanest armies, the root charged—rabid, ardent, vicious, starved, all that stuff—into the corpse. Into its heartless chest cavity.

A moment passed, something pregnant like a sigh. Then the walls burst. Brittle mortar fell all around Tanna, while roots—hairy and haggard, driven by insane thirst—wound themselves round and round until nothing of the woman, not her bits nor her cells nor her zillions of bacteria, was left. Until, in fact, Miss Tanna Kolvea had never been.

Sorough's Hill

The tenants were vague, nameless shadows of indiscernible gender. Myths and legends. But genuine people? Made of flesh? The building had always been vacant as far as anyone knew, so they filled it with legends of sad creatures oblivious to the crumbling walls around them.

But there were the two persons thought to live in a cave on the outskirts of Dornstown, the persons referred to as Angel and Justice, which were of course not their real names, who were thought to have once lived in the house, if there'd ever been one. Except for the occasional less than human clicking sounds coming from the deep recesses of the cave, there was no hard evidence of their existence. Children wrote stories about them, which proved they weren't real.

But fact was, the tree's intricate root system had reordered the architectonics of the building. Rooms were halved and quartered by aerating roots; entire floors had collapsed under the massive weight of the lateral meristems with a bit of help from a massive termite infestation. Then suddenly—or gradually, but the two are barely distinguishable—there was no building at all. And of course there never had been.

What there had always been was a hill. And depending on who wrote its name, it was Sars Hill, Sorrow's Hill, Sorough's Hill, or simply Fred's Hill as some of the locals liked to call it—but always a hill, proving to everyone who came to see it that it had always been a hill.

A perfectly massive, bell-shaped hill—verdant and stately—with a singular, magnificent tree atop it. A banyan, some people said. Some sort of pine, said others.

"So ironic," said a tourist.

"How so?" another asked.

"Sorrow's Hill," she replied. "Get it?"

"Ah, yes. Anything but sad, eh?"

"It's absolutely charming."

"And calming."

"And green."

"Yes, quite green."

"And kind of sexy."