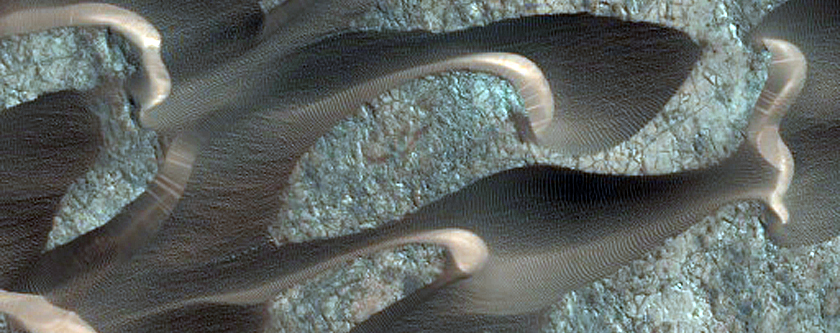

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

When Domkat arrived at Oporoza on that hot and humid afternoon, he immediately set out to find the village bar. Slowly, like someone entering another world, he walked down the narrow, sun-baked road. Surely, he thought, there has to be a tavern in every Ijaw village—a tribe notorious for its bootlegs. Perhaps he will find a guide there, someone to take him to Camp 5. With these thoughts on his mind, he approached a group of children playing homemade drums under a palm tree. They pointed to an indistinct structure down the dust road. Just keep walking, they said, you won't miss it.

He turned to go, but something about their enterprise enticed him to take a closer look. Perhaps it was the unconstrained quality of their play—the care-freeness with which they danced and stroked their drums, their half-naked bodies glistening with sweat. It stirred some old feelings in Domkat—a childhood memory, reckless play in the sunlight, running under a shade of trees—from the rare times he visited his ancestral village in Jos. It occurred to him to record the scene. Why, he thought, the children would make a lovely picture. He could also use the footage to promote the feature story he was working on.

But as he whipped out his camera, one of the children saw him and gestured to the others. Suddenly they broke and scampered in different directions, disappearing into nearby mud huts. Domkat shrugged and started off down the path the children had pointed out to him. Already, an hour past noon, the heat was fierce, nervous sweat trickling down his arms and legs. He passed a stockade of mud huts and bamboo walls forming a barricade of sorts on both sides of the road. Two or three columns of smoke, rising adroitly into the afternoon air from behind the huts, bore the acrid smell of burning fish. The village smelled of fish, of swept dust and decaying compost, and the smell grew stronger as he approached. There were no signs of movement beyond the straggle of goats and chickens wandering about. Yet from behind the shut doors and shoulder high windows, he could feel the unwelcoming glare of unseen eyes following him. He felt like a spy, an intruder.

He continued to walk and look at the countryside around him; the sense of uneasiness gripped him even more. This mission, the interview he had brought himself here to do, seemed rather far-fetched and abstracted from the classic rural settlement he had come upon. Their rudimentary, everyday life lay open to him like an ancient history book. He had come to take change for granted: new buildings, fast cars, the Internet... In Oporoza it did seem as though the clock had been turned back 100 years, when the entire Niger Delta was a stockaded cluster of huts, planted around tiny track roads leading to the river.

He came upon it suddenly—a stunted, battered-looking box of zinc sheets held together by a trap of nails and bamboo sticks. It didn't have a proper door, only a narrow opening in which he had to stoop to enter.

Inside the bar, he was greeted by a draft of hot, fetid air. The semi-dark interior gave the impression of a cave whose walls were lacquered with whitewash. There was a clutter of bottles, tall and short, set upon on a haphazard assembly of tables and worn-out cane chairs. Giant, noisy flies hopped up and down on the tables. There was also a stone grate, stuffed with charcoal, with a small black pot sitting on it. Domkat felt himself clasped by the wave of balmy heat.

When he entered, his appearance elicited no immediate surprise, no consternation, as he had feared it might. Three men sat around a table, smoking and drinking. Domkat went over to the make-shift counter and sat down on a long stool. The bartender—a bearded, pot-bellied man, his hair flecked with grey—promptly appeared from a back entrance. He poured Domkat a shot of the native gin, kaikai, and watched him from the corner of his eyes.

Domkat sipped his drink and dialed, for the umpteenth time, the office number in Lagos, but he couldn't get a network signal.

"You don't get service here?" he asked the bartender.

The bartender shrugged his shoulders. "Hardly," he said. "Sometimes it comes and goes."

Domkat could not believe it. He had studied the maps before setting out. He had checked everything. Surely there should be a GSM mast on the outskirts of the village.

"You mean there's no service mast somewhere nearby?"

"Ah, the Government boys pulled it down a few weeks ago," the bartender said.

Domkat wondered how he was going to overcome this setback. He was indeed on a dangerous mission, and it wouldn't do to be cut off from the office. The terse invitation from Government had promised nothing, not even his safety.

He glanced at his watch. It was getting to two o'clock. Perhaps if he set out immediately, he could cross the creek and return to Oporoza before dark. The distance on the map was roughly 20 sea miles. It shouldn't take up to two hours to cross on a speed boat.

"I need to cross over to Camp 5," he said to the bartender. "Do you know where I can find a boat?"

One of the men turned his glazed, red eyes at Domkat. There was a pained, incredulous expression on his face, as if Domkat had pronounced death on any one who was listening.

"Who are you?" The bartender said, his eyes narrowing. The customer-friendly affectation had vanished, replaced by a wary look of suspicion.

The charcoal blazed and shifted in the stone grate; the small black pot hissed and pissed into the yellow flames; the bar room was hot and sweltering in the mid afternoon heat. Domkat cast a nervous eye at the men around him. He was not afraid, but he knew they carried a drunken threat. He was outnumbered, and they could do anything. So he decided to introduce himself: a journalist from Lagos writing an exposé on militants and their demands.

They listened uneasily, measuring him from head to toe with disbelieving eyes. In desperation Domkat showed them his identity card and a letter relaying his invitation to interview Government Egbomgbolo—son of the soil, militant commander, and king of the creeks. He then asked them for a guide and a boat to sail to Camp 5—the militant camp.

The bartender spoke rapidly, in Ijaw, to the three men who had formed a circle around Domkat. They all burst into laughter. Presently one of the men came forward and shook Domkat's hand. He said his name was Heineken.

"But you don't look like a troublemaker," Heineken said. "Only troublemakers go to Camp 5." Yes, he knew a good fisherman, a man of reliability and honesty, who could agree to sail to Camp 5. He would take Domkat to see the man as soon as he was ready.

2.

Later Heineken and Domkat went out to the waterfront to see the rowboat. A huddle of thatched houses clustered near the edge of the creek, and a zinc house, draped in a fading green and white paint, stood inside the water on bamboo stilts. Pieces of fish were spread out to dry on wire meshes; baskets and fishing nets hung from the thatched roofs. Some thick bundles of raffia thatch and a yellow jerry can were lying near a smothered cooking fire. They stepped onto the pier made from long bamboo sticks. Heineken called out to someone.

A small, thin man, lying asleep on a straw mat under a canopy of palm branches, stirred. "Who is it?" he said drowsily, blinking his eyes at nothing in particular.

"That's Tamuno, the canoe man," Heineken said. "He travels up and down the creek at night and sleeps during the day."

"Where is the boat?"

"There it is." Heineken pointed vaguely to the creek and then went to speak to Tamuno, who was now sitting up on his mat, yawning and fanning himself with a straw hat.

Domkat walked slowly across the makeshift pier and descried the sights around him: streaks of sunlight seeped through the bamboo sticks to reflect on the water surface below; thick vegetation and immense forests rose high around them, going on and on out of sight. Tall palms and banana fronds took turns in hugging the water. Seaweed plants floated by. Perhaps there was poverty in the land, but surely there was a bounty of greenery; even the water, as he peered at it, looked a dull shade of green. A wooden dinghy tied to the bamboo stilts bobbled gently to and fro on the water—it had a paddle, a lantern, a machete, and a bailing pail.

He raised his voice, "Where is the boat?"

Heineken came over, a crooked smile on his face. He pointed towards the floating dinghy.

"There it is," Heineken said.

Domkat blinked and said, "What?"

Domkat opened his mouth to say something, but the words wouldn't come. He had pictured a motorboat, like the ones running the short jaunts to Lagos Mainland—but this: he wouldn't have sailed in his bathtub with it. The thought of crossing Chanomi in what looked like an open coffin, served on a plate to prowling alligators, caused him to break out in a fresh sweat. But more terrors were still to come.

Heineken was haggling with Tamuno. Domkat was still too baffled to speak. Instinctively he reached for his phone and dialed the office line again, but the signal bar was flat. He couldn't get through. He felt abandoned and helpless. He wanted to speak to someone at the head office. Coming to Oporoza alone to score a scoop now seemed like a very foolish idea. To hear Heineken and Tamuno arguing about the fare sounded to him like graveyard talk.

Heineken walked over to him and said, "He says it will cost a lot of money."

"Ask him if he has a motor boat," Domkat said, wiping his face with a handkerchief. "I will pay him whatever he wants."

Heineken flashed another crooked smile. He seemed to be enjoying Domkat's discomfiture. "No sane person from this village will sail to Camp 5 on a motorboat," he said, "the Government boys will hear the noise, and they will surely blow you out of the water with their bazooka guns."

Domkat shivered inwardly. Camp 5 was gradually fading away, and with it his hopes of scoring a scoop. Did he come all this way for nothing? He had the feeling his journey had only just begun, and yet it seemed as if he had come to the end of the road.

He said, "Ask him if we can leave now and return before dark."

Heineken stepped aside to converse with the canoe man, a heated exchange followed, and then he returned with more bad news.

"He says he can only sail at night. The Government boys do not differentiate between friends and foes. He doesn't want them to see him coming."

Domkat leaned on the handrail, his thoughts in disarray. Returning to Lagos empty-handed wasn't an option. The shame would be too great, but he didn't want to die, either. If only he could speak to someone at the office to ask for advice. Then a familiar voice began to whisper in his ear: "No one else has taken a photograph of Government and his gang. It will be a scoop. Your peers will be jealous of you. Besides, Government is expecting you. There is nothing to be afraid of."

He recognized it. It was the same voice that had led him into trouble before. That word "scoop" again. Domkat shook his head. It was like a juicy bone tossed at a hungry dog. No one took him seriously at the office. This story, if he could to get a handle on it, could be his ticket to fame. He imagined his jealous colleagues doing full page articles on him. He saw his face splashed on the pages of every newspaper in the country. He would receive his long overdue promotion, and his editors would have no option but to send him on international assignments.

He said aloud, "Tell him to prepare the boat. We'll sail once it is dark."

While Tamuno got the boat ready, Heineken and Domkat went for a walk along the waterfront. The waterfront was almost a mile long and saddled with baskets, fishing nets, half-drifting boats, and a bevy of ramshackle fish stalls. Some naked children were running around, splashing noisily in the water. Pockets of village women, between their washing and scrubbing, kept them on a leash with watchful eyes. There were vultures everywhere, squatting on the brown sand, hugging the roof of the fish stalls. And the evil smell of decay—rotting fish and blood—seemed to excite them. They flapped their wings and jumped clumsily from spot to spot. Domkat observed all these with some perplexity. Alligators in the creek and now vultures on the shore, he thought. The coincidence rattled his nerves.

Then they met the village school teacher—a tall, dapper young man of some education who spoke in a patronizing manner. Domkat told him of his plans to sail to Camp 5. The school teacher was unimpressed and did his best to dissuade Domkat. The militants were on the other side of the river, armed to the teeth and watching everything with powerful binoculars, the school teacher said. He warned Domkat about how dangerous the creek was. He had seen it all before, he said: people coming from the city thinking they could sail across the creek with ease. The Navy had tried in the past to invade Camp 5 from this route, but they were thwarted. The passage can only be done under the cover of darkness. "You could be blown off the creek at any time," he warned.

Listening to him, Domkat again had the uneasy feeling he was being taken for a fool. The big shot city reporter who knew nothing about village life, whose stubbornness was going to kill him. Heineken and the school teacher seemed convinced he was walking into a watery grave, and while they were adamant in advising him not to sail, he could sense they were speaking about him, whenever they switched to their Ijaw dialect, with pity and amusement. The dank heat and the indignation of their mockery caused the hairs under his collar to bristle. Yes, he was scared, but more than anything else he was determined to prove them wrong—to show them he was not a coward.

It was three o'clock, and night was still far away. Thoughts of doom were preying on his mind, and he needed a distraction.

He said, "Let's go and have a drink."

They retired to the bar and sat outside under a big mango tree. Domkat ordered pepper soup and some local beer. The office had given him a generous allowance, and he thought it might be well to spend the money now, lest it sank in the waters with him. Heineken and the school teacher, surprised at the unexpected generosity, became loquacious and showered praises on him. "That's the fearless journalist from Lagos," they announced proudly to the passers-by. "He is going to write about us."

It was pleasant under the mango tree. The sun sank lower and lower, painting the sky in glowing copper and gold. Shadows fell across the road, lengthened, and drew abreast of the trio. Tired-looking men smelling of fish came in from the river to wash down the day with a drink or two. They came in pairs, some dragging their fishing nets with them.

After a few beers Domkat's spirits began to climb. He felt better, and he began to think of the coming night as an opportunity for a once-in-a-lifetime adventure. He had been born and bred in Lagos, where the only boyhood adventure he could lay claim to was the scaling of dormitory walls for nightly trysts with girls from a neighboring school. This was different—almost spectacularly different. He began to think of himself as Sinbad, sailing on the creeks to establish his name in local folklore. This beclouded vision excited him and made him restless with anticipation.

His companions blossomed, too. They were like buddies who knew they were sharing some last moments with a departing friend, full of cheery advice on the uncertain road ahead. The exotic smell of the mango-trees, the irritating odor of dust, the musty smell of free-flowing beer, seemed to add to their intoxication. The school teacher's powerful voice rose higher and higher with each topping of alcohol. "Ijaw people are patriotic people. We love this country!" he declared in his jocular and condescending manner. Heineken sniffled a lot. It seemed like the pepper-soup was bothering him. With his nose running and tears gushing from his eyes, he nodded vigorously to everything the school teacher said. Soon their table became charged with loud bragging and political talk.

"I wish I could personally introduce you to Government," the school teacher said. "He and I used to be classmates."

"Really?" Domkat said, looking at the school teacher with new interest.

"Yes, we went to the same primary school, and I bested him in every class," he boasted.

"Why not?" Domkat said. "The boat is big enough."

"I have to teach at the school tomorrow, and I don't know when you will be coming back."

"Tomorrow is Saturday."

The school teacher scratched his head and drank from his cup. Domkat ordered more drinks.

"I'll pay you as a guide if you come," Domkat said persuasively.

This seemed to throw the school teacher, for he reacted indignantly—he didn't need Domkat's money. He was a patriotic citizen and not a militant, he said. He would accompany Domkat to Camp 5 just to show him he was a good friend, that Ijaw people are kind people who take care of their friends. "We will sail together on the canoe and discuss the state of the nation with Government," he said.

Domkat felt moved by such noble talk, to have inspired such patriotism, such camaraderie in only a few hours. Presently Heineken took off his shirt and started waving it in the air, claiming it was the Nigerian flag. They shook hands and raised their glasses to One Nigeria.

Impetuously the school teacher turned and called out to everyone sitting around him, "I'll be escorting the journalist to Camp 5 tonight, to prove that Ijaw people are peaceful people. We are not militants."

The school teacher was making a status for himself. People gathered around admiringly and he began to explain the mission to them. Listening to the school teacher, Domkat felt a sense of careless oblivion overspread him. What had started out as fear and foolishness had transformed into an act of pride and heroism. He basked in the boastful talk and smiled indulgently at the people who came to shake his hand.

An elderly man appeared with a bottle of schnapps and poured libations on the floor. He prayed for a safe passage and a friendly reception on the other side. Heineken pranced around taking pictures with Domkat's camera. He wanted to capture the historic moment, he said.

A small boy carrying an ice cooler came into the bar. "That's my son," the school teacher said, and called out to the boy. When the boy came over, he patted him on the head and Domkat overheard him saying, "I'm going to Camp 5 with an important man from Lagos. Tell your mother I won't be coming home tonight." The boy's eyes lit up with wonder, and he ran home to tell of his father's great undertaking.

3.

Domkat hadn't realized how close the night was. One moment he and his comrades were patting each other on the back, reaffirming their determination to see out the journey, and in a blink the sun had disappeared and nightfall was suddenly upon them. They set aside their drinking jars and made their way to the waterfront by the light of Heineken's electric torch. All around them the noises from the bush whistled and crackled as they passed: a few fireflies flickered here and there; the grass rustled like newspaper; a frog croaked miserably to complete the ensemble.

Domkat quickened his pace. Soon they were approaching the banks, where he could feel the leafy ground giving way to a soft, slippery soil. There was a sudden cartwheeling, a loud crash, and Heineken`s torch went flying into the darkness.

"I stepped on a snake!" Heineken cried, breathing heavily as he rose from the clump of shrubbery where he had fallen. He picked up his torch and began to swing it around, like a man confronting a swarm of vermin. When he had satisfied himself the snake was absent, he went out to fetch Tamuno.

With the deep sky and the stars pouring over him, Domkat stood beside the school teacher and looked towards the creek and the huts nestled peacefully among the mangrove trees. How still it was, he reflected, with only the hushed voice of the waters whispering ominously through the reeds. In the shimmering darkness, the voice was like strife upon his soul, cutting him in two minds: to turn back and return to Lagos—to safety—or to lap the sea and sail to an uncertain fate. He saw the stars drawn across the sky like sad tears looking down on him. Perhaps there was great sorrow in the eyes shedding them, he thought. Indeed, the setting appeared to him like a dark, protean cave, threatening to swallow anyone who entered it.

Heineken and Tamuno soon emerged from one of the thatched huts. The latter gathered his net and unhitched the canoe. No one said anything. Domkat and the school teacher stepped in and sat on the hard, stern seats.

Heineken was flashing his torch from the banks, guiding the boat as it sailed away. Presently a troop of mosquitoes fell upon the boat and its occupants. Domkat looked at the school teacher, who sat hunched, head bowed, as though a great weight was upon his shoulders. He was by now aware of the school teacher's loud airs, but this meekness, this effeteness, made him another person. The school teacher batted ineffectually at the mosquitoes and muttered inaudibly to himself. When they were about 50 yards away from land, Domkat said to him, "Are you sure you really want to come?"

Domkat could see the school teacher's eyes glint in the darkness. He looked remorseful, shame-faced. He murmured something about his wife—that she was pregnant and he could not bear to have her worrying about his whereabouts—and without waiting for Domkat to respond, he dived into the water and swam quickly to shore. From the banks, his disappearing shadow waved and shouted, "Send my greetings to Government!"