Electronic/fiber artwork by Phillip Stearns

Three weeks ago, Johnson Martin saw a black triangle in the sky while standing outside his home smoking a cigarette. It soared slowly through the air with no sound. Green and yellow lights danced along its perimeter, and a white light shone from its center like a great porcelain dinner plate. Johnson Martin ran out into Main Street, finger to the heavens, screaming from deep in his belly, They're coming! They're coming! We hardly paid mind, as everyone knows Johnson Martin is off his rocker and always spouting religious nonsense and conspiracies and the whole gamut of oddities you'd normally expect from city folk. Not long ago, we endured his Main Street sermons on the black Muslim movement storming through our town on the way to Washington, DC. He said he was trying to rally support, but Johnson Martin is one of the only blacks in our town, and the other blacks—Carl Washington and his family—are wise enough to not fall in with Johnson Martin's antics. So who ever believes a thing Johnson Martin says, anyway? Besides, the very next week if you'd ask about it, he'd say, I dunno nothing bout no triangle! And then he'd spit his chew right by your feet. It'd sit there, a congealed brown mess. You'd breathe it in, the foul pungent scent of phlegm and tobacco. And then you'd walk away cause you learned better than to make conversation with Johnson Martin.

The Kagnan boys say they saw a strange man—at least seven feet tall by their account—through a curtain of tree trunks as they were playing in the woods. He wore green tweed-knit sports coat and had a wide, long, flat face with a broad grin sculpted into stillness stretching to the back of his skull. The boys froze, and the Grinning Man froze, and they watched each other.

We hear the Grinning Man has no nose or ears, that his eyes are thin and there is too much space between them, that his flesh is hued sickly green the way Samuel Keele gets when he goes fishing. When the boys circled around him, the Grinning Man followed them with his face and nothing more. His body still, his head would turn and rotate with them as they moved. The boys heard the Grinning Man speak. He said the word cold, but his lips never broke from that big grin. That was when the Kagnan boys ran, trees and branches and dirt blurring past. They looked once behind them, and the Grinning Man still stood erect, unmoving, watching. And then they continued to run, as far as they could. Past the big hollowed out birch tree. Past the tree house near the Halloway place built for young Edgar decades ago. Past the Birchmere Farm and on and on till they got home, not once stopping for breath.

We paid closer attention when Brandee Birchmere started on about the Grinning Man. Such a sweet woman, no one could be more honest. Brandee says she was on her pap's farm driving the tractor to hoe up the fields for planting. She reached one end and drove in a big arc to circle back around, and there he was, tall as a spruce and as wide as a stallion. His fine green jacket flapping in the wind, his smooth green face grinning ear to ear. Now, after the fact, the Kagnan boys say they think—after thinking it through—the grin was a friendly one, not so sinister as they first thought. Brandee, though, she says to us the grin was perverse and lecherous, with wanton lust in his spaced eyes. And what do young boys know of lust, anyway, save the filth they watch on the television these days?

She stopped the tractor and stared the man down, and he stared her down, grinning all the while. Again, he never moved, not an inch, not a twitch to his lips or a blink to his eyes. Just stood and stared. Stood and stared, like he was waiting. Suddenly, the chickens began a raucous in their coops, and Brandee broke her gaze. Then she says to us when she looked back—not two seconds later—the Grinning Man was gone.

Now, we did go to check the farm, of course. All of us. And there wasn't a trace we found in that soil. No shoeprints or prints of any kind except some rabbit tracks. Later though, at Keele's Tavern, wouldn't you know we found threads of green tweed on our boots and shoes? Then a hush fell over us, and fear kept us from speaking until Edgar Halloway declared softly, Something's not right with our town these days. And then there was more silence because we knew he was right.

By Saturday, the Grinning Man was on all our minds. Who was he? Why had he come to our town? What was he doing to our folks? Billy Gardner swore up and down his wife was different. Cold, he said, like her mind had been scrubbed clean on the inside with a toothbrush. Then he said the other night, when he was leaving Keele's Tavern, he saw Old Maggie Anne talking to a tree in the woods. He crouched behind some bushes to watch, and sure as April rain there was Old Maggie Anne, head crooned up to a tree.

Billy Gardner had the mind to walk the other way and take the long way home. And as he was turning, he realized Maggie Anne wasn't speaking to a tree at all. It was the Grinning Man. So goliath, his brown slacks had been mistaken for a tree trunk. His green sports coat mistaken for leaves. The Grinning Man made eye contact with Billy, and Billy says the grin stretched further to a sinister width. That was when Billy took to running.

And earlier today, someone saw Old Maggie Anne walking into the river with her clothes on. Word spread around she went and killed herself. We wonder how lonely she was, living in that old farm with just her cat. The older of us remember when Old Maggie Anne was Maggie McIntyre, the young pride of our town. Her hair was as red and shiny as the flesh of sliced grapefruit, her frame slender; we still laugh at the way she would relentlessly flirt with Clemson Bullock—may he rest in peace—and then go out and reject his every advance.

The younger of us remember Maggie as the pretty woman who always brought chocolate milk from the McIntyre Farm with her when she babysat us. Back then we adored her.

But Clemson Bullock fell terribly ill, and Maggie changed. Month by month, Clemson declined. He aged 30 years in a single one. Young, taut flesh pruning into rows of wrinkles on his brow, Maggie Anne at his bedside aging right with him. By the end of it, Clemson Bullock was gone, and Maggie Anne's soul evaporated in grief. She didn't speak to any of us anymore. Sold her milk and returned straight home, never a peep. Years later, she sold her cows and stopped working entirely. The McIntyre family had 60 acres of woods in our town dating back to the colonial days, and she went and sold nearly all 60 to the state government. Now it's a park city folk tourists come to camp and hunt in when they want a taste of the real world.

The idea Old Maggie Anne—changeling or not—would walk into the river surprised not a one of us. And after Billy Gardner's story? We were expecting something of the sort. Later we saw Maggie Anne walking back from the grocery store dry as wheat. We all kept our distance. Maybe she really was Old Maggie Anne and no one had walked into the river at all, but maybe she was the changeling and made Maggie Anne go and drown herself.

Now, the more sensible of us are skeptics. Carl Washington went and called our town a den of fools. He says our imaginations are running from us, full sprint. That we ought to slow down and think for a second. Some of us agree, but most are growing scared. Carl Washington's words provide some comfort. They make us think we got nothing to fear from the Grinning Man. That he ain't even real. We just got an idea in our heads, that the Kagnan boys are spinning yarns and got us all spooked. We're just seeing the Grinning Man in every shadow and every tree in our town. And our town's got a whole lot of trees.

After that we feel safe and we laugh at ourselves. Carl Washington is right, after all. Den of fools.

But then a dry storm consumes the sky. Lightning snaps through the clouds. Static hangs in the air and stands the hairs on our arms and legs. When we look up, we can't help but to see forms behind the clouds, eruptions of light like raining meteors and electric orbs; we see shapes of saucers and triangles in the sky. What else are we supposed to think but the Grinning Man? He sent them here. He's one of them. And, within minutes, we all believe again cause what other proof do you need? Any fool can see they're coming, that we're under siege.

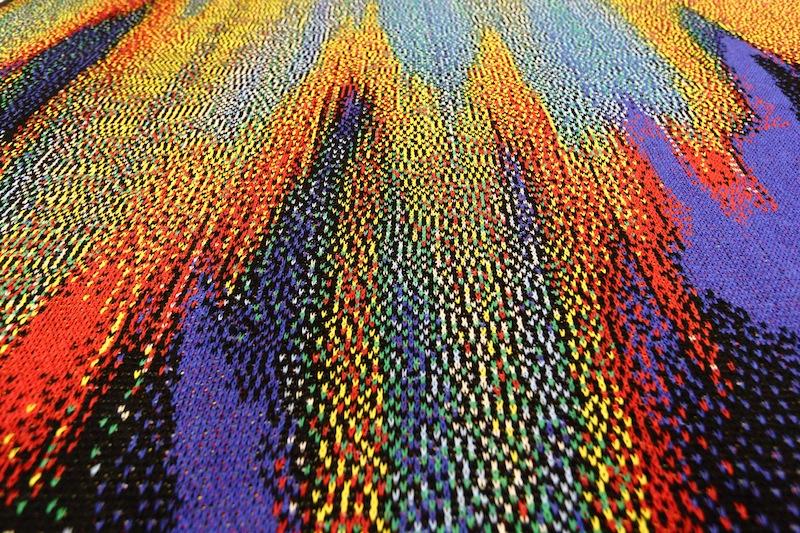

The sky is streams and ribbons of color. It crackles with electric booms like Chinese firecrackers in the clouds. Orbs fly, a thousand little sentient moons floating deliberately through the air. Some collide. Some zig, and others zag, ravenously exploring their world. The sky draws a faint outline, a massive black triangle over our town. When we look up, we fear and are humbled. Some see doom. Others see God.

Everywhere we look, the Grinning Man is there, shadowed between trees. We see his face, still and grinning, when the lightning flashes. In anger, Billy Gardner explodes from the doors of our liquor store, shotgun in hand. We yell to him, Billy! Billy, no! Until there is a gunshot, a flash of light, and then another shot. The booms tear through the air. When the smoke and dust clears, we wait and stare at the darkness of the woods Billy Gardner shot into. When an orb spits up light from the sky, we see a tall and green and grinning figure, towering and still.

We run.

All of us—half the damned town at least—push into Keele's Tavern and board the doors. The bravest of our men gaze out the windows to see the Grinning Man and the tempest of swirling orbs of light. Our women comfort our children. To medicate the anxiety, our men drink from the taps some more.

From time to time, we see his face in a window, gazing. We wonder if he can see in the dark, see us huddling together so close. When we look away, he is gone. Samuel Keele mutters something we can't hear and then digs out a revolver and a mason jar of shine. He says, The shine's for coping. The gun's just in case. And we pass Keele's shine around, even the women.

An hour passes. Maybe more. We hear the Grinning Man throwing rocks at the walls. The sound startles the children. It keeps us alive, wakes in each of us our fear. Stirs our anger back up with each stone thwacking at the walls.

Edgar says, Our town is stronger than this! And he takes Billy's shotgun and blasts a shot out a window. The sound deafens us, and we feel weaker, more defenseless than before. Our men get angrier. We can no longer tell who we are angry at.

Our men leap out the window, Edgar first. We think tonight he has always been the strongest of us. Tonight we think Edgar is the greatest of us and we would lay our lives down for him. We pretend to not know Edgar sleeps with Billy Gardner's wife and that one of the Kagnan boys is his, too. We are drunk on cider and rage and terror.

Edgar fires at the trees indiscriminately. We are not sure if we can see the Grinning Man anymore. We are sure we see the Grinning Man everywhere. Up high in the tree tops. Down at our feet, buried in mud. Grins everywhere. Green everywhere. The flashes of light—of the sky and of the guns and the oil lantern someone has brought (we cannot tell who in the shadow the lantern creates)—blind us.

For hours we wander in the woods behind Edgar's lead, cheering and shooting and roaring. From time to time, the Grinning Man's face appears between trees and bushes, and immediately we fire. Sometimes, his face disappears with our shots; sometimes it remains, unfazed, staring and grinning a big old grin as we run riotously away. Even the Kagnan boys are with us. One of them points and says, Look! Down the trail!

We see it. His shadow is enormous. He stands centered on the trail, broad and dark and still. We freeze in shock. The longer we stare, the more mammoth he becomes. It is dark, but we swear his grin glows faintly. He shifts his weight, and Edgar roars, He's brought them! They're coming for us now, don't none of you dare let him get away! And we roar with Edgar. The Grinning Man runs away from us, his shadow shrinking in the distance until we chase after. There is so much noise we hardly hear anything but ourselves. Then there is another boom—our boom. And the figure falls.

Edgar reaches it first. We prod at the body as we wait for light. The man with the light is far behind. Someone says, Looks awfully small!

No! shouts another. That's it! The Grinning Man! I've seen it!

Johnson Martin belts, We have killed the menace! We will be free!

When the light comes, we crouch to the body. And then we turn away as something somersaults in our stomach and we feel ill.

Someone whispers, Old Maggie Anne. We killed her.

Someone else argues, She was one of them! Don't you remember?

We shoot accusatory glances at one another. We wonder: who fired? Edgar with the shotgun or Keele with his revolver? Many of us hold firearms. We remember gripping the handles in white-knuckled vices. We remember our fear and outrage. When we look up and gaze through the canopies at the swirling lights above, the guttural rumbles of the sky, we don't know what we're looking at anymore.

Edgar is silent. He lifts Maggie Anne into his arms. Come on, he says soberly. Let's go back.

We follow.

It is quiet as we return, the gnawing sort of silence, the silence of sound. Insects buzz, birds call, thunder rolls, our boots clop-clop against the packed dirt beneath us. Its rhythm beats our shame into us. When we are back on Main Street, we see Carl Washington approach. He asks, What the hell happened?

Someone yells, The sky! The Grinning Man brought them!

We realize how absurd it sounds.

Carl shakes his head. He spits out, Damned fools, the lot of you. And look who had to pay. Watch the news sometime and stop sipping Keele's shine all day. And then Carl Washington walks on and away.

We look at each other, bewildered, ashamed, certain and uncertain all at once of what transpired and what we saw. We talk amongst ourselves while we deliver Maggie Anne to the hospital. Edgar stays with her, and we talk back at Keele's too. Our women confirm the Grinning Man's face leering in through the windows and the thrown stones. Our men remember the Grinning Man standing in the woods, his body a skyscraper over Old Maggie Anne. We remember how he dragged her deeper into the wood, and how she screamed at us for help, and how Edgar dove ahead and fired at the Grinning Man, scaring him off. And when we looked down to retrieve Maggie Anne, we noticed then, stray pellets had struck her. We pass the story amongst ourselves until we are sure of every last detail, until we have wrung it of every drip of truth. And then we drink.