| Oct/Nov 2013 • Salon |

| Oct/Nov 2013 • Salon |

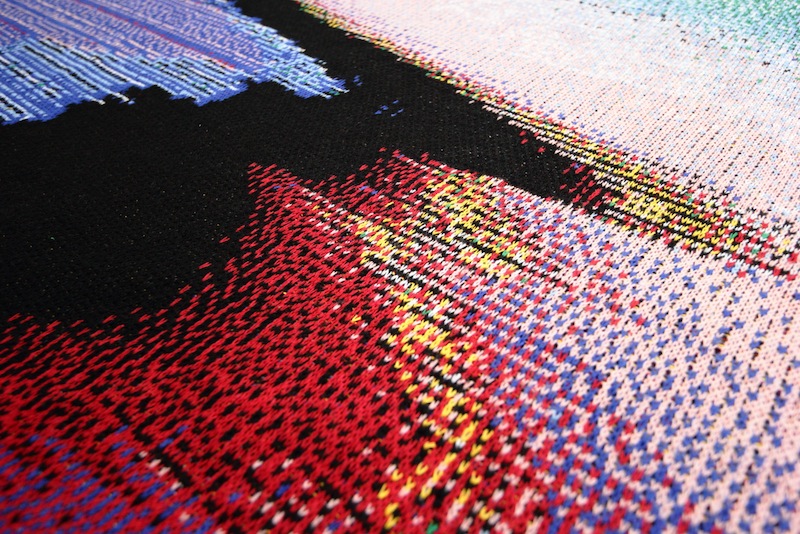

Electronic/fiber artwork by Phillip Stearns

Scarcely a day goes by without someone quoting George Orwell. The term "Orwellian" is common enough that it should be used without capitalization. His warnings about how language molds thinking, which in turn molds politics, is as true for our society as it was for the overtly totalitarian ones that existed in the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. But I'm beginning to wonder if a different cultural reference isn't just as relevant as Orwell, perhaps more so.

"The Grand Inquisitor" is the title of a chapter in Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov. In that chapter Ivan Karamazov, who is about to leave on an indefinite, perhaps permanent sojourn, relates to his younger brother Alyosha an idea he has for a play in which the Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition confronts Jesus, or someone so like Jesus as to make no difference, and takes him to task for returning to earth and meddling in the affairs of the Church by healing the sick and raising the dead. He voices his outrage in a dungeon where he has had Jesus locked up. He, the Inquisitor, does all the talking. Jesus just listens.

The gist of his lecture to the Savior of the world is this: Don't come back here and muck things up, when it's taken so many centuries for us—meaning the Church—to finally give people what they need and want: bread and something to believe in. You, Jesus, when you came the first time, offered them freedom, the Inquisitor says, using the gospel story of Jesus's three temptations after his 40-day fast in the desert at the beginning of his public life. In that gospel, the devil, or, as the Inquisitor calls him, "the wise and dread spirit, the spirit of self-destruction and non-existence" and "the wise and mighty spirit," tells Jesus to turn stones into bread to appease his hunger, then tells him to throw himself down the mountainside to prove he cannot be injured because he is the Son of God, then offers Jesus all the kingdoms of the world if Jesus would bow down and worship him.

Jesus rejects all three temptations because, according to the Inquisitor, he had come not to offer humankind bread or miracles or empire but the opportunity to believe freely and to freely choose for themselves. But humankind, the Inquisitor says, has shown time and again it doesn't want freedom or, more to the point, when it thinks it does cannot handle it. The Church offers them, along with bread, "miracles, mystery and authority," and this is what makes for the greatest happiness of the greatest number. True, the authorities, the Inquisitor and the others in charge, know it's all a sham. But if tens of thousands must lie so that tens of millions shall be happy, that is a price worth paying—and is much better for the tens of millions than what you, Jesus, offered, thank you.

The Inquisitor, it's very worth noting, is not only 90 years old but, he assures us, and does so convincingly, acts as he does out of genuine love for humanity. In his youth he believed in Jesus and freedom, but he learned from long experience the folly of those beliefs. And now he will not brook any interference in the fruits of the hard work he and others have brought forth—the daily executions of heretics and others notwithstanding and in fact applauded by the people, just as they will approve Jesus's own execution the next morning despite the healings he has performed for them that day.

But, don't take my word for the Inquisitor's good intentions. When he finishes his monologue and, with an apparent change of heart, tells Jesus to leave the dungeon and never come back, in effect reprieving him from a second execution, his prisoner rises and kisses the old man tenderly, showing that he knows the man to be as well-intentioned as he claims to be.

Lift this product of Ivan Karamazov's imagination out of the context of the liturgical, put it into the political, and you have what seems a paradigm for the crisis that confronts our democracy, and has in fact been confronting it since its inception. There is nothing new about the tension between freedom—"liberty," as it used to be called—and authority. Ordinary people were never considered fit to govern, having no substantial economic stake in the society and little if any education in its affairs. The greatest good for the greatest many is best decided by men of property and the right kind of political thinking. This was the same attitude that denied women the vote and preached that chattel slavery was a benevolent institution based on nature and good Christian principles.

But it was only in the 20th century that "manufacturing consent," to use the phrase of its most prominent proponent Walter Lippmann, came into its own, thanks to the development of the public relations industry. Ironically, that industry dates from the days of the Espionage Act during the first world war when President Wilson needed to mobilize public opinion in favor of the US's entry into that war on the side of the Allies—the same legislation our current president is using to prosecute Americans recognized by some as whistle-blowers and denounced by others as traitors.

Since then controlling public opinion not through imprisonment or autos-da-fé but by molding it carefully in the mass media has become a refined scientific enterprise that requires no physical coercion in democracies like ours, even in the way of oversight, as long as the right people, the modern secular equivalent of the Grand Inquisitor and his partners, own or control those media. The propertied class of the 18th century are still in control, and they have not changed their opinion one bit about their prerogative and duty to decide what is best for the tens of millions.

If Dostoevsky's Jesus was the enemy of the Grand Inquisitor, Plato should be considered his best friend, as he is for his modern equivalents whether they are called Neocons (many of whom studied under a neo-Platonist at the University of Chicago) or corporations (legal persons under our law) or their agents in the highest positions of government. Plato's idea of the best government is a model that has been used by all authoritarian regimes ever since he promoted it two and a half millennia ago. The Espionage Act, the Patriot Act, the Stasi, and all the other more or less obvious means of controlling not just the actions but the thinking of the majority by the elite would all look familiar and good to Plato. He recommended, among other things, that every citizen of his Republic be surveilled constantly and that religion be used cynically to control the "masses," to use a modern term for what the ancient Greeks called hoi polloi (literally, "the many").

We have heard and read a lot of references to George Orwell in recent years, especially to his dystopian novel 1984 that portrays a world in which everyone is constantly watched and continuously indoctrinated. But, maybe "The Grand Inquisitor" is as apt or even more so to our current political circumstances. We see people in other parts of the world take to the streets and demand their freedom, in the so-called Arab Spring most notably but also in places like the Republic of Georgia, in Kenya and, after two centuries of its northern Big Brother's hegemony, in several nations of South America. We Americans seem by contrast all too willing to accept "bread"—despite its constant diminishment for most of us—in return for our freedoms.

Why? Have the manufacturers of consent and their neo-Platonic economists succeeded so thoroughly in turning us into the docile drones the Inquisitor and his Greek forerunner claimed was the best condition for humankind?

Freedom as it was conceived just a few centuries back, like democracy, was a new and dangerous idea. Till then only the sovereign, like the God who ordained him, was free, and democracy had for 2,000 years remained a pejorative term meaning not self-rule but mob rule. In proclaiming our liberty and our right to govern ourselves, we are challenging virtually all of recorded history. You can't do that and get away with it without constant vigilance and an informed citizenry. Even the aristocrats who created this nation recognized those imperatives, however much they intended to limit them to their own kind. If we choose to believe otherwise, we will simply lapse back into the perennial condition of virtually all past human societies—authoritarian, ignorant, and grateful for the bid of bread we are allotted by those who know what's best for us.