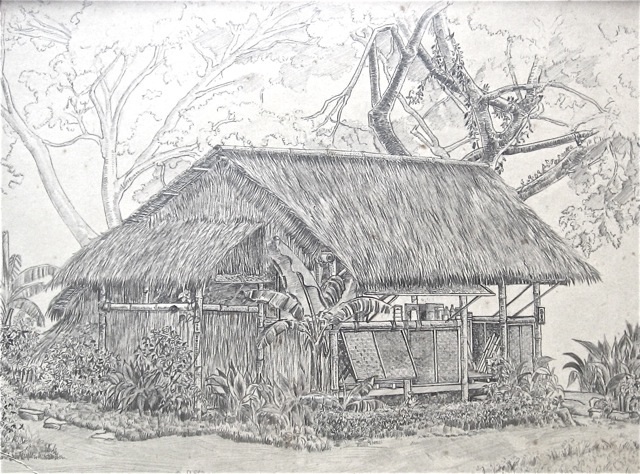

Sketch of Johnny Oldfield's shanty by Donald Dang, 8/8/44

1

People go crazy for fireworks. Shoot off a few lights into the sky, a couple of good booms, you get a crowd oohing and aahing in a shot. But not me. I hold out for memory. If I could just bring back a few months out of this last year, I bet I'd have you oohing and aahing big time, too.

It wasn't just one thing like a light show. It was everything, fireworks outside and in all at once. It's not that easy to tell just what it felt like. The closest thing I can come up with is for you to lie down on the railroad track and listen to a big diesel coming, first a long ways off, then closer and closer, building and building, bigger and bigger, until all at once it's shaking your eyeteeth right out of your head. You want to yell at the top of your lungs, it's so big, so loud, so much to take. But you're too busy holding your breath and praying. Then, while you're all in a sweat, it stops. You don't know if you've been hit clean out of this world or it all just went away. You shake all over and cry like a baby. And you know why? Because you're weak. Those sons of bitches made you weak. Kept cutting the rations and cutting the rations, until you were limp as a dishrag, and an old rotted-out, mildewed dishrag at that.

Me and Polecat figured we had it beat. We were young. We could run and dodge. We weren't like those poor old fogies with purple veins running down their skinny legs and beriberi creeping up from the ankles to the knees like poison, like slow floodwaters easing up toward their hearts. Beriberi was a killer you could watch, level by level, puffing up the joints. And even if me and Polecat were lean as cur dogs at the garbage dump, no beriberi was ever going to get a shot at us.

You'd see old guys down at the Gymnasium, skinny and yellow with the jaundice, so tired they could barely get themselves to roll out of the rack in the morning, taking long loud-snoring siestas in the afternoon, then easing quiet as shadows back into their dark racks at night. They played a lot of chess, those old birds, slow chess, sitting long and quiet under the acacia trees, looking deep into each other's hollow eyes to see if they could see old man Death lurking there in their neighbor.

It got so you could count on two or three or even four a day going out in plain wood boxes. And you know, not a whole lot of surprise or ceremony got shown by the rest of the Camp. I guess it's what we'd come to expect. They mentioned which names to cross off at roll call and even said a few words at chapel, but all and all, those boxes passed out of Camp with about as much of a ripple as a burial at sea. Just a few little kids scattered along the path to the front gate singing, "Didja ever think as the hearse went by that you might be the next one to die?" Only there wasn't a single hearse anywhere in sight. Not even a horse-drawn carromata. They'd just wheel them out on these little handcarts. The kids always sang nice and cheerful, putting a sweet little emphasis on the part where "the worms play pinochle on your snout."

Mom, who was working nurse at the Santa Catalina Hospital, told me most of the old ones died pretty quiet, just got weaker and weaker, with the diarrhea usually, and then sort of slipped off. But one geezer yelled and cursed all night in his sleep for three nights running, came up with wild word combinations Mom never heard before. When he finally croaked, the rest of the patients were pretty happy about it. Relieved. Seemed like peace and quiet had got to be more important for some than staying alive.

You cut someone's daily ration down to a dipper or two of thin rice gruel—lugao, they called it—and you will definitely cut down on that person's energy. Some of those old birds would've blown over in a light breeze. Some of them couldn't even wait long enough to get to the hospital. Too impatient. Died right in their beds, right in their chairs. One old lady was so quiet about going, she sat most of a day in her shanty before anyone noticed she was a bit too still. Her jaw drooped a bit was all, and she'd quit snoring.

Now here's the funny part. Every time the Japs cut the rations, this old guy we called the Colonel would say in this real loud voice, "You got to take the bad with the good." That would send Polecat rolling into hysterics. We loved that old coconut plantation philosopher.

"What do you mean by the good, Colonel?" I asked. He was no army man, but once grew coconuts for Peter Paul's, those chocolaty candy bars. And after the Japs'd taken my dad's pals, Harry and Southy, out of Camp, we started going to the Colonel for our answers. He just scratched his head and smiled at us.

"Why would a Jap want to starve a poor Yank?" he asked real solemn and mysterious, like it was the last question in some holy test for monks.

"I asked first," I said.

"Cause we're beating the piss out of him, sonny. We've looked at him hard and long. We've stared him to a standstill. Now at last we've unleashed the dogs of war." Polecat really loved that.

"Unleashed the dogs of war!" Polecat repeated, smiling like he just had breakfast.

"It don't feel like we're winning," I said. "What's telling you we got the upper hand?"

"Don't you hear the news," he scolded.

"You mean all those names of battles we're supposed to remember? All those downed planes and sunk ships? How many killed? It's nothing but our rumors against Jap propaganda."

"The tide's turned, boy," he scoffed at me. "When you hear 'Guadalcanal' and they take away your meat, that's victory. When you hear 'Midway' and your last shred of chicken disappears, that's glory. Now you just heard 'Leyte' and you're slurpin' gruel, Johnny. What's that tell you?"

"We winning big!" Polecat shouted. But I couldn't put a good face on it.

"Couldn't we cash in one little battle for a bunch of bananas?" I asked.

"No, you stonehead," the Colonel said. "You got to give to get." I shook my head. If this was victory, I could wait a long time for peace.

But I'd discovered my own secret formula for staying alive. Sticking with Polecat. He was the best hater I'd ever come across. And I was damned if I was going to let him out-hate or out-last me. Hate is strong medicine. People talk a lot about "Love thy neighbor as thyself," but for staying alive in a prison camp, hating is the best. Keeps your mind sharp. Gives you resolve. Anytime I had any notion of letting down my guard, I'd take a good look at Polecat flashing his gap-toothed grin and it gave me a backbone of pure steel.

Every place me and Polecat went, he'd want to race. Sure, he knew damn well he could run circles around me with those wiry mestizo legs of his. We'd be off and dashing along under the trees, me straining and puffing to stay close. And every time, just when I felt like I was going to bust a lung, he'd look back over his shoulder, smile at me wicked and taunt me, "Sige na! Hurry up!" Every time I ran, I knew I'd lose. But I knew I had to keep on running till I dropped. Polecat was my cross against the vampires. My silver bullet. And if we died, which we never held likely, he was damn sure going to die first.

Thank God my old man taught me boxing. That was one I'd always have on Polecat. He was quicker, tougher, maybe braver. But boxing was one place I brought superior education to bear. My old man learned the skills and passed them on to me. As long as a ref was standing in, making sure everybody lived up to the Marquis of Queensbury, I had him licked. And as luck and the Commandant of Santo Tomás Internment Camp would have it, those were the conditions we battled under.

Just when everybody was getting so low on energy he thought every step would be his last, we got us a Commandant who believed in the Olympic Athletic Ideal. Maybe you never heard of the Olympics of 1944. Somebody told me they canceled them all around the world. But they were held, sure enough, in Santo Tomás Internment Camp.

"Your problem is not diet," our new Commandant announced to us with a big smile. "Your problem is lack of exercise." Well, you can bet your last Mickey Mouse Jap Peso he got a good groaner from the crowd on that one. You take a man who's been using his last ounce of energy concentrating on keeping his heart beating and tell him it's now high time to skip rope, and you're bound to break that man's concentration.

It was mid-afternoon. We were in direct tropic sun. Around three and a half thousand starved internees had been standing attention for two hours waiting for this new Commandant to come and greet us. Seven souls'd already fainted dead away in the Main Plaza. And he'd no sooner arrived and taken his first look at us than he recognized just what it was killing us. We were under-exercised.

It was tough enough just to think about exercise in the third year of our incarceration. It'd been a few months since anybody had even so much as suggested tossing a softball or swinging a bat, so we were a little slow to catch on at first. But folks did give it a try. And, as you probably figured, the tossing and the swinging were the least of our problems. They weren't near as tough as running to first after you got a hit or running down a ball lofted over your head into centerfield. I noticed those World Championship Games kept getting shorter and shorter. And, in a little time, everybody got so skilled at playing, they could figure out who won in three innings and quit right there, instead of waiting the full nine.

But that Commandant didn't stop there. He had the true Olympics in mind, with all kinds of races and acrobatics and exhibitions of skill and endurance. The highlight for us young guys was the pugilist's art. And that was my game. They built a real ring—four wood posts, three strands of rope. They handed out the ten-ounce gloves. And they divided us up by age and weight. Me and Polecat were in the division called "Flyspeck." Every day we had a different match, three rounds of what Hollywood calls "slow motion." You could've made a movie at regular speed and people would think you'd monkeyed with it to make it look soft and lazy like some artist of the cinema.

Me and Polecat dragged ourselves through three such matches into the finals. He got there on street guile. But I still had a lot more hours practicing under my old man's eye. Polecat knew I had the footwork and the jab, the old left-right-left combination. So he tried to trick me. He came up with this little dance. Sort of a rumba or a samba, I think. He came at me kind of off-center, with a big grin on his face and a little hitch in his rear that got everybody laughing. I could hear them chuckling and snorting all around me outside the ring. He was moving so many parts to the rhythm, I could almost hear the drumbeat. Somebody was saying, "I do believe it's Fred and Ginger!" But I was Spartan as my old man taught me to be. I stuck to my business.

About three-quarters through the first round, just when Polecat looked like he wanted me to Charleston, I caught him a pretty good one flush on the side of the head. It stunned him, caught him off balance and put him on his rear for a second or two. He lost all his sense of humor real quick. That put an end to butt twitching. And once he quit laughing and dancing, he lost his rhythm. He kind of lunged and stumbled through the rest of it.

I wouldn't be the one to challenge Polecat in a dark alley, but with ten-ounce gloves in the light of day, I could keep jabbing and moving pretty good. At least, good enough. Yeah, he gave me a red cheek and a runny nose, but I knocked him down twice and drew some real blood. A couple of good shots right on the button did it. Got his respect, I could see it. And if I never won another thing, at least I took those three rounds off Polecat. Even if he said the decision "stunk like a rice paddy" and swore everybody from the ref on up to God must be blind, I got the bamboo cup.

It was a beauty, carved from a section of bamboo pole, my name and all the details of my heroic exploit etched and colored on the side. "Flyspeck Champion of Santo Tomás." I know Dad would've been proud. Polecat glanced at it sideways and licked his lips. Pure envy narrowed his eyes.

But if he was worried, he didn't have to sit around long waiting for my glory to fade. I'd no sooner put my cup on the shelf in our shanty than I saw the first dust falling. That hunk of bamboo had bak-bak and I had to watch it sit there and crumble. That guy, old Ozymandius, from a poem they made us recite in school, thought he had it bad. "Look on my works ye mighty and despair." At least he got a couple of thousand years to admire what he'd done. No one ever got to despair over my works. Not even Polecat. Ozymandius might've had some drifting sands to curse, but he never had to put up with the bak-bak. I barely saw my cup whole once. But as the Colonel said, "You got to give to get." When just a little pile of those termite shavings were left, Polecat's feelings started to mellow towards me again.

2

You're asking where are those fireworks? Well, just be patient. You know you got to start with the little rockets first and build. I've got to set the stage, tell you more about this hate business of Polecat's. When I first met him, he spread it all around like grass seed. Wherever it landed, it sprouted and grew pretty good. He hated all us colonials pretty much as good as the Japs. So he spent a lot of energy practicing on folks who were supposed to be his allies. But along about the second year of Camp, he started shifting it all over onto Jap sentries and the Commandant. Finally, by that third year, with all that valuable practice behind him, he got so he could really concentrate and narrow it to just one person. And that was a Jap named Abiko.

Abiko was head of the Guard and about as mean as you're ever likely to run across. First off, he looked nasty, with a long sour face, a shiny shaved head and high polished boots, strutting by and looking around like he was searching for someone he could swat for being insolent. There were sure plenty of reasons to hold a grudge with that villain. I saw him haul off and sock a lady just because she didn't give him enough of a bow. You see, he was the one who stood us all out in the hot sun for about three hours, keeping us at attention while he taught us, all three and a half thousand, individually, the high art of the Japanese bow. Just so from then on, twice a day at roll call, we could bow correct to the Japs.

But there's something funny about the American body. It doesn't seem to bend right in the middle. Even with starvation, it was awful hard for us to get down the real deep respectful Jap bow. Most folks didn't mind a little head nod once in a while, but they'd been shying away from that folded-at-the-belt variety. Abiko marched up and down the ranks dealing harshly with our obstinate breed. He grabbed people right out of line and gave them private lessons till they got it right. He pushed down and rapped them on their heads and shoulders to help them fold themselves in ways they never dreamed possible.

Then he laid down strict orders. From then on we had to bow to every solitary member of the Imperial Japanese Military, even your run-of-the-mill sentry. It didn't make any difference if you said you didn't see him or not. You had to bow or else. That lady sure didn't get it right that time with Abiko. She didn't bend the way he'd taught us. In fact, I'd say her bow was a whole lot more like a twitch. Abiko didn't offer her a private lesson. It was too late for that. He hauled off and punched her silly. Matter of fact, he broke her jaw. And that's what set Polecat off.

Abiko's bowing class got him mad enough. But you wouldn't catch Polecat bowing if he didn't have to. He'd always spot a sentry far enough off to slip behind a shanty or start walking off in the other direction, yelling out to some imaginary buddy across a field. But when he heard about Abiko breaking that lady's jaw, he started pawing the ground. He wasn't even there when it happened and it drove him nuts. He swore his vengeance. From then on Abiko was Polecat's private vendetta.

The Colonel tried to talk sense into him, but Polecat didn't seem to be buying any. We were sitting on the bamboo floor at the entrance to the Colonel's nipa shanty, looking out across the great open field where Abiko was training raw recruits. They'd come into Camp dragging these old wood wagons by hand, straight out of some rice paddy, most likely. Things were getting thin in Japan, I bet. The field was big and yellow now under the hot sun, and Abiko was sweating his tunic through.

"What you think makes that Jap so ornery?" the Colonel asked us. Abiko was barking orders at the recruits, but they were awful green. Even I could tell. All left feet and not a thumb in the crowd. Abiko was getting close to the end of his leash.

"Who cares?" Polecat said. "Putangina." He blew a cloud of blue smoke into the shadowy air. We were smoking what we called the War Pipe. The Colonel had this long showy corncob pipe, kind of like old General MacArthur's. We'd go around picking up any butts we could find lying on the ground all around camp, bring them to the Colonel's shanty and shake out all the tobacco into a little pile. Then we'd fill her up and have us a War Pipe. I took a slow drag and started coughing.

"Maybe he don't like bein' a Jap," I offered.

"You boys know about shinto and bushido?" the Colonel asked. He looked grand when he smoked. It was his old yellow mustache and the way the smoke curled up through it and then around his eyes.

"I think I heard of 'em," I said. "But just can't remember."

"Monkey talk," Polecat said. But the Colonel set us straight. He said this shinto stuff was like a religion where the Japanese islands and mountains and woods and such were the gods and the Emperor came straight down from the sun in the family tree and was a god himself. They weren't even supposed to look at him, he was so special. So they went around bowing all the time, afraid they might look up and see this god and be blinded or burnt to a crisp or something. It was pretty strange stuff, I can tell you that. Bushido made a Jap want to die for the Emperor more than go on living day to day.

"So why does that make him mad at us?" I asked. "We don't care about his dumb islands."

"Hell, boy, he's not mad at us for wantin' his islands. He's mad cause we're even living this close. Cause we're not his Asian brothers. Cause we walk around like big shots from America and don't believe in his gods."

"We make him very happy," Polecat said. "Give him a big bushido and kill him for the Emperor." He had his pocketknife out, clicking the blade in and out. Just then Abiko hauled off and kicked one of those recruits in the ribs and sent him squirming and whimpering in the dust. He had those young Japs crawling back and forth across the field all afternoon, just trying to keep their rifles off the ground. But they looked like they'd never seen a rifle before. And never wanted to see another one again.

"He's mad cause they're losing the war and they got nothing left but a bunch of dumb farm boys who stand around grinning," the Colonel said. "He's probably the only real soldier out of the whole bunch in here. Heard he was in the China campaign and took a bullet in the gut. So he got this sorry prison camp detail. Maybe he's mad cause he's not out at the front someplace."

"Looks like he's sure mad at those young Japs," I said. The Colonel took a long drag off the corncob and held the smoke inside awhile. He was thinking. Then he blew the smoke down through his nostrils like little darts. It made his eyes light up and get teary. He looked awful wise.

"He's embarrassed," the Colonel said. "And there's nothing makes a Jap madder than being ashamed." But Abiko persevered in his kicking and hollering. And it was pretty amazing. By the time the long shadows reached out across that dusty field, those recruits were keeping their rear ends down and crawling pretty good. Kind of like alligators and crocodiles. I guess if you're halfway good at what you do and keep at it, you can make something fanciful out of a sow's ear. Why if he'd had another year, old Abiko probably could've even got those birds to march in step.

Polecat loved to call Japs "monkeys." He'd do his imitation of Abiko every time we were with the gang. It came from a speech that Jap gave us at roll call when they couldn't account for some poor sap on the roster who'd just been transferred from the Camp Jail for being drunk and disorderly to the Hospital for being sick and dying. Anybody with half a brain should've figured out he couldn't have been there even if he would've. But after about a half-hour of this frustration, Abiko went stone-faced and started yelling in Japanese, because his men couldn't get their numbers straight. Then he started pacing back and forth and speaking to us in this real low stone voice. He mispronounced his English something terrible.

So after that, Polecat lined us all up—Red and Jerry, Pete and Knockers, the whole gang—and started his mimicking, with big, stiff steps, like he was carrying a long samurai sword. He could do it real good.

"You American say Japanese are monkeymen. But we are supermen. We all supermen!" And we'd all pull in our breath and bow to him—that big, deep bow we never did for the real Japs.

"Ohhh!" we'd say all together. "Velly collect, rootenant!"

But then things happened that really stirred Polecat up and got him buzzing inside like a soldier bee when you mess with the queen. When Abiko punched that lady, Polecat sure went bananas, but she repaired herself by and by. Maybe she had a toothache and found it hard to talk straight right off, but when the swelling reduced, she looked pretty much the way she always had. But the next two things that happened bang-bang hard on each other, they could never be made right.

First, we heard sentries caught two Filipinos during the night. We never did hear clear what went on, but Polecat said they were hoisting food over the wall to Americans, some kind of smuggling where they got caught red-handed with the booty. Well, maybe so, but if they'd been heaving stuff over the wall, how come they got caught and not the Americans who were on our side catching it?

Pete Bailey said there was a whole gang of Filipinos that beat up on a Jap guard or two, and they all got away save these two who couldn't run fast enough. Well, that sounded a whole lot closer to logic, so I leaned to that story. But you can see what we had. We were just like a horse with blinders running at the racetrack. He can run and run, but when it's all over, he's got to ask some other horse to find out who won. There we were in the heart of Manila, right in the middle of the action, but with that big masonry wall all around Santo Tomás, we couldn't tell what was happening in the street right outside unless we had a good rumor to believe in.

They dragged those two poor Filipinos into the front section of Camp, up by the Main Gate, where Abiko had early on made a work crew put up a sawali fence. That made it tough to see. Sawali's woven together like a mat, so unless you find yourself a hole, you can't see through. But me and Polecat and Pete crowded up there with some others and found us a peephole where we could see them tie those poor boys to posts and beat on them with bamboo clubs. And you could hear them cry out and groan in pain just as plain as if you were right there beside them. It made us sick to watch it, but we stuck it out, first Polecat looking through the hole, then me, then Pete, until their bodies sagged down unconscious. Then we went away, feeling low and vengeful but stupid, because we couldn't do a thing. I heard one died and the other was thrown in a cell in Fort Santiago, where his broken bones all knit wrong and he was crippled. That's what I heard. I don't know if it's the truth. And that whole time I only heard Polecat say one thing.

"Fucking funny monkeys."

But something like that's most always catching. I guess everybody concerned was plenty edgy. The Japs were putting a lot more time in on practicing their martial arts and such. You'd see them out on the big field, early in the morning, dressed in just those fundoshi g-string things, doing their exercises, getting ready. Then you'd see them all duded up in bamboo suits of armor, whacking on each other fast and furious with bamboo poles. Polecat said they thought they were Ivanhoe or something, which was a book we had to read in our Camp School. But those old knights used metal swords and armor, so there was more of a clang-clang sound. This was more of a thwack-thwack. Polecat guessed maybe they got confused about which war they were supposed to be fighting.

"Next week, they ride horses and joust," he said. We got us a good laugh over that craziness.

But there was nothing funny about what happened the next day behind the Jap Commandant's Kitchen. Polecat got me over there to scout the joint for something. He was cooking a plan, I knew that, but he wouldn't let me in on it just yet.

One of the yellow curs that ran around Camp was there, all skin and bones like the rest of us. He'd got himself adopted by some Japs who hung out around that place. He was lying real quiet in the dust, just out of the sun, conserving his energy. Every once in a while he'd cock an eye to see what was passing by. Or maybe scratch for flees, or snap at a fly, or lift his hind leg and lick at his balls. That dog had himself a pretty good life by Santo Tomás standards. Most dogs and cats had been skinned and eaten by local connoisseurs in search of protein. This one never moved out of the shade except to get a scrap from some Samaritan Jap every third or fourth day. They always cursed at him and teased him plenty, but all in all, they treated that dog pretty good.

There was this threesome of sentries there too, up on the porch, sort of lounging in the sun, laughing and discussing things among themselves. They had those bamboo clubs, and every once in a while, they'd kind of rap them against the side of the porch, just to hear that thwack. They called out to the dog a couple of times, but he'd just maybe twitch an ear or slap his tail on the ground. He was too tired to do more. When the dog didn't hop to and come over, one Jap started yelling at him. That opened the cur's eyes and got his tongue lolling, but nothing more. The Jap kept hollering, getting himself angry and sweated up, but it wasn't doing him any good.

One of the others said something and went into the kitchen. After a bit he came out with a piece of raw fish in his hand, bent over and held it out and talked sweet to the dog in a coaxing voice, like that hound was his closest and dearest friend and he couldn't do enough for it. After a while the dog must've sniffed what the Jap had, because he got himself up, kind of stiff-legged and cramped, and limped over to get a taste. Meantime, the other two Japs sort of slipped around behind him and came in on his flanks.

The first one snapped his club down like he was chopping wood, real deft and hard across the dog's haunches with a solid crack that knocked him to the ground as if he'd been shot. When he tried to get himself up, he found his back legs didn't have any life to them, so he could only yelp and whine and snap out in pain and drag himself round in circles. But when he bared his fangs and snarled, the other one cracked him hard across the muzzle. That looked like it had done for the dog, and the others yelled at the Jap for killing it too quick, I suspect.

But it seemed like the dog was only stunned, and he got himself part way up again, blood coming from his mouth and nostrils, snorting and shaking his head in a red spray. Then they moved in and started working on him more methodical, laughing and shouting at each other for turns. Oh, they did have themselves a merry time, just whacking away at that dog with their clubs like he was the fiercest enemy they could think of. Finally he lay there without moving at all, blood clotting in the yellow fur and dust. They poked at him, hoping to get a growl or a whimper, but he'd had enough. It took my breath away, I want to tell you. Left me speechless.

Polecat just shook his head and came over and put his arm around my shoulder.

"Come over here," he said. "I want to ask you something." When we got further from the kitchen, he nodded back toward the porch. "What you think's in the big can?" There was this metal drum up on the porch and he knew as good as I did what was in there.

"Don't know," I said. "Food maybe?"

"How'd you know?" Polecat asked.

"I saw them dipping into it. Some kind of sauce or soup or something."

"Then how come you say, 'Food maybe?'"

"What do you want?" I asked him. "What kind of craziness you up to?"

"They put it out fresh every day. I'll be by your shanty after dark," he said. And, oh boy, I thought.

"How about Pete and Knockers?" I said, figuring it would be good to beef up our ranks.

"No good. Knockers says his old man's too sick. Pete's mom won't let him out after curfew."

Late that afternoon, those new recruits moved their wood wagons to the edge of the big field and camped themselves down for the night within spitting range of our shanty. I watched them straightening out their stuff for the night, then settling down to have some chow. But it made me too hungry and sad seeing those guys together like that, eating and talking. So after my mom left for the Hospital, I went and sat down at the back of our shanty all by myself where there was this muddy ditch that ran along under the acacia tree with a shallow trickle of water in it. Even there I could hear them chattering away, kind of soft and pleasant, sometimes laughing. And behind that I could still hear the click and clank of mess kits and pots and stuff, so I walked up the path, trying to think of something else. I was kind of nervous, to tell the truth, wondering just what we were going to get ourselves into. Finally, when it was getting near curfew and everything was quieting down all over Camp, I went back to the shanty, kicked off my shoes and lay down on my cot, thinking of my old man and missing him. I did that when I got nervous. I guess it was natural.

I concentrated real hard on his face. Gosh, I was fond of him. I never could forget in a million years the way he came towards you. He had a kind of forward lean, real physical, like he was attacking life. Seemed like he just loved every minute. I figured maybe he and some of those other miners up in the Benguet could've become guerrillas, hiding out in the jungles and swamps, ambushing Japs and stuff. Boy, I wished I was with them. That would be the life. Thinking about that made me feel better about going off with Polecat.

Sometimes I'd dream about Dad coming over the top of the wall to rescue us. Lots of people come up with the worst thing that can happen. Like how somebody's going to be tortured or executed when we don't even know where those people are for sure. But when you think about it, that's pretty stupid. My old man was plenty resourceful. He was a very strong person, too. He really was. You give me a choice, I'll come up with the optimistic picture for you. I figure if there's something bad on the program, I'll find out soon enough, and then I'll deal with it.

I must've drifted off because the next thing I knew, Polecat was pulling at my foot and whispering my name from the edge of the shanty. It was getting pretty dark.

"Get your dinner pail, Johnny," he whispered. He didn't have to say anything else, and I kept my mouth shut because I didn't want the Japs out front to hear. We snuck soft as shadows out the back and up along the path under the trees towards the Education Building. The night had got so thick you could barely make out people when they slipped by. Everybody was moving back to where they were supposed to bed down for the night. It was so quiet I could even hear the frogs singing way over in that ditch along the wall. And even though we hadn't had an air raid yet, there was a blackout all over the city, and on the ground floor of the Education Building the lights were all shaded. That's where a lot of Jap officers were quartered. When we got closer I could hear muffled talking and laughing deep inside.

"Drunk," Polecat whispered. "They're plenty nervous." We walked along slow and casual, swinging our dinner pails like we were just out for a stroll. Nobody was near the Commandant's Kitchen, just a dim light from inside throwing pale yellow squares onto the lawn. No window at the front or back, just a door that was shut. But I heard a Jap voice, kind of far away, chattering inside the kitchen someplace. Then, while we were standing there, straining to make out who and where it was, this bat darted low, right over our heads, squeaking. It was enough to give us the willies.

Polecat handed me his dinner pail and disappeared onto the porch. I backed in close to the shadows and stood still as a tree, looking back out, studying the road off to the side. The lid on the can clattered and Polecat cursed. Not loud, but you could hear it. I was holding my breath like I had my head under water. But it stayed so quiet, I could still make out the frogs and that little far-off voice talking to itself inside. The voice had me spooked until I finally figured it out. It took me long enough. But there was no other answer for it. It had to be a radio. I felt like a sap, standing there getting nervous over a radio voice, but it'd been so long since I'd heard one.

Finally Polecat reached out of the shadows and grabbed a pail. Then quick he handed it back heavy and dripping with some sticky liquid. It smelled fishy. I handed him the other pail. Then I heard the lid again, real light this time, and he was right there next to me and we were walking together back across the road and down the path under the trees towards my shanty. I was thinking to myself, boy, that was a cinch, we could do this every night, when all of a sudden I saw this big shadow looming towards us up the path, and then I saw the outline of the helmet. It pretty near stopped my heart. In the snap of a finger we'd come from "home free" to "cooked goose."

We just froze there in front of him and Polecat right off gave him this real low bow. So naturally I followed suit. I didn't want to stand out. All the time my mind was racing on what excuse we could come up with for being out past curfew with our dinner pails full of Jap sauce. But before I'd even begun a plan, I heard Polecat saying something real loud and clear in Japanese.

"Konban wa, Abiko-san," he said just like he was a Jap native. And both of us like statues, bowing as low as we could go. For what seemed a lifetime, the Jap stood there like he was trying to figure out what he wanted to do with us. Finally, without saying a thing, he gave a low grunt and went on up the path.

"That was Abiko?" I whispered when we got back to shanty. "What the hell did you say to him?" Polecat set his pail down and started laughing like crazy and trying to hold it all in at the same time. I kept asking him what he'd said, but it took him a full five minutes before he could answer. Every time he started to talk, he'd break into the shakes.

"Konban wa is good evening," he finally confessed. "And then, Abiko, sir." Well, there's no telling what a so-called friend will do behind your back. All this time Polecat was posing as a Jap-hater, and here he was talking just like he was one of them.

"How'd you know how to say that?" I asked him.

"I figured it'd come in handy," he said, still grinning like the smartest little mestizo on the face of the earth.

"Well, you sure fooled old Abiko," I said. Then he started sputtering and shaking all over again, only harder, and it took even longer this time before he got himself straight.

"Not Abiko, you sap. Not Abiko."

"If it wasn't Abiko, why'd you say, Abiko-san?" I asked him. And after he told me, I could've slapped myself silly.

"Who's that Jap most scared of? Abiko. Just the name made him think, I bet. Mixed him up bad. He probably thinking right now Abiko maybe knows us. Maybe like buddies." One thing I'll give old Polecat every time, he was as quick a study as you're likely to find for a tight situation. I felt like I'd just tripped over my own two feet.

But, damn, we felt big and heroic. We sat in the dark on the back step of my shanty and slurped that fishy sauce and kept giggling and trying to hold it in until our stomachs hurt. We came pretty close to the hysterics. Guerrilleros. That's what Polecat called us. And he made me swear I'd go with him on another big raid.

"Yeah," I said. "Someday." I was proud as punch. That sauce was so good and rich, it made us kind of sick to our stomachs. So we saved most of it, closed up our dinner pails, cleaned them good outside so the ants wouldn't crawl all over them and put them down under the shanty floor for the next day. Then Polecat slipped off to the Gymnasium so he'd be there in his cot when everybody woke up.

Next morning while Mom was still sleeping off her night at the hospital, me and Polecat did some serious bartering. Those farm boys camped out front were so wet behind the ears they never even thought where we got our sauce, so we traded them even, one dinner pail of sauce for a whole mess of fresh-cooked rice. You should've seen us there with all those crazy Japs around us, smiling and pointing at the sauce and then at them and the rice and then back at us, like we were in some bazaar, until finally we struck a deal. And those guys were pretty nice to deal with, all in all. We still had one dinner pail half-full of sauce and more rice than the two of us could eat in a week, so we went over and fetched the Colonel. And when Mom got up, we had us a real feast.

You consider what we'd been eating along with our lugao on a regular day—worthless greens like telinum and pechay and kangkong and pigweed. You figure we were so hungry we'd even chopped down a banana tree behind our shanty, sliced the trunk up like an onion and ate it boiled. And all we got out of it was a little bulk and then the runs. Well, you can see what all that rice with fish sauce spooned over it must've tasted like. We just sat there in the shanty, barely even chewing, just letting it melt like sugar in our mouths, smiling at each other like we'd been born again.

The Colonel ate real good and my mom ate good and still nobody said one solitary thing about where it'd come from. They just seemed to accept it like "manna from heaven." That's what the Colonel called it. He said we should be as happy as the Israelites with this unexpected gift tossed in our laps by Providence. The old guy sure had a way with a phrase. Like we were out in the desert somewheres and God was looking after us. I tell you, it made me feel pretty good.

But then I took a good look at Polecat who was grinning at the Colonel like he was nuts. And I figured it out. Here we just pulled off this slick raid and then duped a bunch of Japs into trading for rice, and along comes God and takes credit for everything. The tough thing about being secret at what you're doing is you can't own up to anything. If you've done something good and don't jump on it quick and take the credit, somebody else is going to grab it. But after Polecat and the Colonel took off, Mom put her hand on top of mine, real soft.

"Look at me," she said. So I looked at her real close. She looked kind of miserable and wrung out, to tell the truth. I have to say it. She was still nice looking, with those green eyes and pale yellow hair bleached even lighter by the sun. She just looked bushed. Kind of dark around the eyes and her hair all sweaty around her forehead. I guess it must've been hard on her, being a parent to me all by herself, since I was at such a difficult age. I guess it was easier for her to be a nurse under the circumstances. "Promise me, Johnny, you won't do this again."

Well, what could I say? First someone took all the credit, then I got all the blame. It was hard enough just to work yourself up to go on a raid without some woman swearing you against it. I guess that's why guerrillas are so set on not having ladies running around on bivouac. They'd never get to do anything. But I thought it over a minute and saw a way out. I figured no matter what me and Polecat would do, it couldn't be just like this time. I mean in some way, shape or size, it wouldn't be exactly this. Right? So I squared myself up, looked her right in the eye and swore to her with all my heart.

"OK, Mom," I said. But she just kept looking at me like she needed something more. Isn't that just like a woman? Always wanting something more. Something exact. It's like she had to see it in writing. "OK, OK. I swear I won't ever do this again."

About then Polecat was starting to sound like the local expert on the Jap morale. Everything that happened was just one more sure sign that they were about to crack. "Look at all this stuff they're dumping in here," he said. He grabbed me to show me some big crates of machinery they'd just unloaded at the end of the field across from the Education Building. "You see, you see." Then he made me go look at gasoline drums they were burying over by the Camp Garden. "Pissing their pants, Johnny," he said. Then they started dragging in these big rolls of heavy wire mesh. "Know what that is? Know what it's for?" he kept asking me. "Airstrip!" he said, real excited. "So they can escape in a airplane. Hah!"

Polecat started dancing for real when the first air raid came, even though we never saw a single plane and the all clear sounded in less than an hour. Just the sound of the siren wailing got them digging in the ground all at once, and if you asked Polecat, that was the best sign of all. The Japs were ordering up work details to build air raid shelters. And all these new Jap units came rolling in and out of our camp starting all kinds of rumors. Like the one that they were going to ship us all out of Santo Tomás to some other camp.

"That's a real good one," Polecat said. "They don't know what to do—run like a dog, fly like a bird or dig like a pig. I tell you this Jap Army's real fucked up."

Me and Polecat built our air raid shelter right under the back corner of the shanty. And it was fine. First we dug out some ground back there, only we couldn't go too deep because the water would start leaking in. Then we went out to the big field where the work crew was cutting squares of sod out of the lawn. We got a bunch of that sod and piled it all around the hole we'd dug to protect us from bombs and such. When we were all through, we put a sawali mat on the ground and crawled down there like it was our secret place. It was good and cool on a hot day. And there was many a night it became our home. It fit me and Mom and Polecat with room to spare. Sometimes we even invited the Colonel to come in and join us.

The Commandant wasn't so lucky. He had a work crew start digging a big hole right out in front of our shanty. It was going to be the special air raid shelter for his car—this big black Packard roadster he had requisitioned off some poor American who'd lived near us out in Pasay. I remembered it from the old days. We sat there and watched while a crew dug and dug to make it big enough and deep enough. Until one day their hole sprung a leak and filled up like a swimming pool. The Commandant came and inspected it and just shook his head and looked sad. After all, it was such a grand plan. An air raid shelter for a whole Packard! You got to admit, that's a scheme.

For a long time that hole just sat there gathering water and mosquitoes. But finally someone came up with this ingenious plan to make it the Commandant's Carabao Wallow. Polecat loved that. "The Official Carabao Wallow of the Imperial Japanese Commandant of Santo Tomás," he'd say, very serious, and then tickle himself silly.

They chained the Commandant's pet carabao out there—one of those big-horned Filipino water buffaloes—and that carabao made himself right at home and luxuriated in it. Probably the finest time of that beast of burden's life. I mean, to beat out a Packard! Polecat and Pete and sometimes Red would come by just to look at him. They'd ask, "Johnny, how's he doing? He keeping all right?" like I owned him. At night that big fearsome-looking beast made a real special sound. Not big and bellowing like you'd expect, but a small mewing call, like a cat's. It did funny things to your head, that sound. Sometimes I'd wake up hearing it in the night and lie in the dark, dreaming I was back home and there was a cat down in our garden.

3

About now, you're probably ready for one of those big spellbinder flares that go up and up and kind of explode out of themselves in a way that makes you think you just saw eternity. And it just so happens one of them came along this day when we were all in the middle of English Class. Well, we were really in the middle of "Gunga Din," which had run over from English into Arithmetic because it was our teacher Miss Clark's second favorite poem. Her all time winner was "The Highwayman." She liked poems that went on and on. Sometimes we'd miss out on Arithmetic altogether.

Polecat was doing this big dramatic part, which was to keep saying "Din! Din! Din!" whenever there was a pause in this girl Millicent's reading. She had this real English accent and then Polecat would add this Filipino accent to the Din part. So he'd go, "Din! Din! Din!" And then back in would come this little chirpy English voice saying, "You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!" It was a stitch to hear the two of them, specially Polecat, and me and Red and Pete pretty near split a gut. Since he was a mestizo and all, maybe Miss Clark figured he couldn't handle much more than just the "Din! Din! Din!" part.

There we were right in the middle of Gunga Din at the Camp School on the roof of the Main Building, when every plane in the whole God damn American Army and Navy showed up. Somebody was shouting outside and everybody ran out into the bright sunlight, leaving old Gunga Din in the dust. We all stood around with our mouths open, searching the skies, our hands shading our eyes, just yelling and pointing.

Then there they came, far off, drawing out of a big white thunderhead, small and silver like a school of fish in the deep morning sky. When they came closer, you could just start making out some kind of markings on the lower ones, but there were even more above them, and still more above them, little glints of silver you could barely see, with smaller planes darting around among them like minnows. When they got still closer, they broke off into different bunches, banking in the sunlight. My God, it was something to see!

But even with that, there was this one dumb kid from another class standing there, just shaking his head back and forth, sad and forlorn, while all the rest of us were screaming our fool heads off.

"Them ain't our planes," he kept saying like he was at a funeral. "Them's Jap planes."

And Red said, "You're just stupid, kid."

But the kid kept up with "Them's Jap planes." Just shows you how tough it is to make some people happy. Like the Colonel once told me, you show some folks the Garden of Eden and they'll say it looks pretty much like Iowa.

Polecat said he could even see bombs falling. He was dancing there beside me, all sweated up, pointing to each bunch of planes and shouting out their targets. It did get your heart pumping!

"Look at them!" he was yelling. "Grace Field. They're kicking hell out of her." The building shook like an earthquake had hit it, and then you saw the smoke rise in a big black cloud. "Pow!" He slammed his fist in his hand. Then he grabbed my arm and spun me around to the south. "Nichols, Johnny, they're hitting them at Nichols too." He was jumping up and down with both arms around me. "Look over there, Johnny. Sweet Jesus, look at that. That's Nielsen, baby." Now the machine guns were chattering all across the city, and then came the pump of the pom-pom guns. You could see little clouds bursting in and around the planes while they were moving out away from us. But there were no Jap planes up there. Where were the Japs? "No monkeys up there, Johnny. They all run for the trees."

"Din! Din! Din!" I was yelling and laughing, lost in the power of it. My God, there is glory in destruction!

And Red he yelled "Din! Din! Din!" back. But Polecat was having none of that.

"Fuck Din too," Polecat said. You had to love him. He knew when school was out.

By the time the next bunch of planes came over, the siren'd gone off and they ordered us all off the roof. We tried to look out through the windows downstairs, but the monitors kept pushing us back into the hall. We had to stay there in the corridor, crowded with everybody in the dark, feeling the bombs rock and shake the building. It got too hot and stuffy in there and everybody was real still and hushed, listening for what was going on outside. I don't like being crowded in tight with a lot of sweaty, nervous people. When it was over, I was rung out and pretty shaky myself. And then we had to wait for about a half-hour in the chow line. But we ran into some luck. The rice that day had a little scraping of fish in it. We took it over to the shanty and sat there waiting for the planes to come back.

They weren't long coming. We crouched by this big tree and watched them. Mom was trying her damnedest to get us to go into the air raid shelter, but we were hypnotized. This time there were dive-bombers too, and they streaked in on targets over Pandacan and the North Harbor. Polecat kept darting out to the edge of the field for a better view, then giving a little jump and running back to yell close-up at us where they'd hit. The sky was so loud with the roar and drone and chatter and the sirens wailing, we could barely hear him. That's when I saw my first P-38 Lightning, with those two bodies stuck together, flying along as lovely and proud as an angel. Then we saw dive-bombers go into a cloud of smoke out over the harbor, and all of a sudden one of them caught fire and started to skid downward and screech like a big wounded beast out over the acacia tops. There was no mistaking that awful sound out of the engines and that black smoke trailing off behind. It pulled so hard at you it was tough to keep your eyes clear.

"Help him, God, help him," my mom was praying. And you could see she meant it, because her eyes were all red around the rims and her hands were clutching at her sleeves. I could just see in my mind the poor guy in that plane diving right into the flames and burning up. Made me feel hollow. But Polecat was still dancing like it just turned New Year's.

"Just one, Johnny. That's the only one we saw them get the whole time."

That first day was a whopper, and it wasn't even over yet. Late that night this big explosion just about knocked me right out of bed. Me and Mom looked out the front of the shanty at this huge red glow lighting the sky. Then there was another explosion and a high leaping yellow flame that kept growing and stretching itself out until the whole horizon glowed red and yellow together. The Japs had their searchlights going, too, crisscrossing each other and scraping across the bottoms of clouds. At night it got even more mysterious and wonderful than in the day, drawing you in towards it so you couldn't hardly sleep. You had to keep getting up and looking, afraid you might miss something.

You had to know the next day was going to be tough times at roll call, all of us just standing and bowing while Abiko got into a whole new set of rules. First off, we learned we were all in very big danger and it was the job of his Imperial Army to protect us. That caught me a little off guard. I was sneaking looks at all the guys round me who were working overtime just keeping a straight face. From now on, he said, we had to go right into our shelters when the air raid sounded. If we weren't in our shelters, bad things would happen.

Abiko gave us this very serious lesson in Japanese. He taught us two words. And he got his real deep growling voice on for it, too. He kept repeating these two words over and over like we were all morons. If anybody was found outside his shelter during an air raid and a guard said, "Tomare!" that meant "Halt" and you better stop right there or get your ass shot off most likely. There was just one excuse for ever getting caught out in the middle of an air raid and that was "benjo" which stands for "bathroom." He marched back and forth for about two hours, giving us all this hog slop about how we were under their special care and these rules were for our own good.

After roll call was over, seemed like no one wanted to leave the Main Plaza. Everybody just sort of shuffled around kicking at the ground and smiling. There was this one old codger who could barely stand he was so weak, and he was smiling so hard he couldn't keep his upper plate in his mouth.

"I sure am glad Abiko told us about this benjo place," he was saying. "I figure if it keeps up like yesterday, I'll be pretty much livin' full time at the benjo."

After it broke up and we wandered away from there, Polecat lay down in some tall grass under a banana tree, crossed his legs real comfortable and smiled like a crocodile.

"Abiko is one very nice guy," he said. "You never need a papa or a mama if you got Abiko. He will love you and take care of you and make sure to protect you from the bad Americans. By golly, he's the best damn Jap I ever saw." He looked so comfortable there, I lay down right beside him. But no sooner was I at rest than he jumped up again like a crazy, whipped out his pocketknife, and started carving a circle in this bare spot of ground. "That's Manila. You're the Japs. You go first, Johnny-san." He gave me this deadman stare like I was his worst enemy on earth.

I played along with him. It was a kind of mumblety-peg we called "territories" or "war." We chucked the knife into the circle, carved up the pie. He always beat me at this game, so I was glad to play the Jap side. I groaned real loud like it hurt every time he stuck the knife deep into my territory. When he was all through carving me up, he wiped the blade on his shorts, snapped the knife shut, bowed low to me and said in this super-low voice, "So vely solly, Abiko-san." Then he whipped the blade out again and held it up in front of my face. "Someday, I'm going to stick this in that Jap," he swore, dead serious. Then he flashed me a crazy grin, like maybe he was joking. Only I knew better. I guess we were all on the verge just then.

No, let me take that back. I hate it when somebody tries to make excuses and smooth over the truth. On the verge, my ass. Like we're supposed to believe we're our real selves only when things go easy and all we have to worry about is going to school. But that's not true. I gave it some hard thought one day. I believe the way you are when there's no food and bombs are falling is maybe closer to your real self.

You take Polecat. As far as I could see, he was thriving on those times. He'd run around checking things out all over the Camp. You wanted to know something that happened inside our walls, you asked Polecat. He was so many places, you never knew where to look. Like the time he just up and disappeared. I mean gone. I looked for him high and low for about half a day and couldn't find him anywheres. I asked Pete and Red, but they hadn't heard a thing. I was kind of scared to ask too many, to tell the truth. You never knew just what he was up to. Then we found out at roll call he and some other guys'd got caught looking at a dogfight after the siren blew and the guards grabbed them and took them to the Jap compound, up front, back of the sawali fence. I didn't see him for a couple of days. And I got plenty worried. Then all of a sudden, there he was, standing right in his regular place at morning roll call, just like nothing happened.

"Jesus," we said, all excited. "What'd they do to you?" But Polecat played it real tough. He should've had a cigarette dangling out of his mouth, he was so tough.

"Games," he said with this funny smile. "They make us stand at attention on this log and look at the sky. Balance. You like to look at sky, they say, you look at sky. If we step off the log or try to bend our knees, they start bangin' our legs with clubs. Funny monkeys." He showed us the bruises on his shins.

"Boy, how long you have to do that?" Pete asked him.

"Seven hours, maybe eight. Till after dark. Don't worry, I play their games OK. Only that old guy over there he passed out." Polecat pointed out this poor old sickly-looking bird. He sure didn't look too hot. "Fell off and started kicking." But you could tell Polecat was loving it, like he'd just won the game.

And you take Mom too. She was always pretty religious and all, going to mass on Sunday and making sure she had something on her head and genuflecting at all the right times. That was always her nature, only she was moderate about it. But after that first big air raid, she was there for matins every single day, and vespers too if she wasn't at the Hospital. Well, what can you say? She needed it, I guess. I think it was that plane going down in flames that did it. It might've been something else at the Hospital or her worrying about me, but I think it was that dive-bomber and the way it screeched going down. That's my theory. It's funny, you would've thought she might have started sooner, when we got separated from my old man. But she waited for that plane. She wasn't fanatic or anything. She just needed to pray a lot. And the thing is, I think that was closer to her real self than any other time I knew her.

Anyway, we got lots of practice finding out who we were. Those raids went on pretty constant for something over four months. It was living on the high wire. Sometimes you'd never even see them but just hear an air raid signal and then far-off explosions and drifting smoke. Sometimes just two or three planes'd streak in and strafe and be gone before you even had time to look up. Sometimes big booming waves of bombers'd come slow and steady like they ruled the world and blast hell out of a whole section of the harbor until you thought nothing was going to be left. And the Japs'd be pumping every ack-ack gun they could muster, shooting about a billion little clouds into the sky. Then fighter planes'd go up and have a go at each other, climbing and banking and diving with that nasty screech, every machine gun going at once.

Sometimes they'd catch us unawares when we were just walking up a path and we'd run like hell along the shanties till we got to a clearing where we could watch. Sometimes we'd jump and cheer until we wore ourselves out. But when the roar and thud of the big planes was too close and awesome and heavy, we'd just lie close to the ground under the shanty, with a toothbrush jammed between our teeth to cushion the impact, and hope the bombs went away real quick.

Then the all clear'd blow and every kid in camp fanned out across the grounds to see what had fallen out of the sky. We picked up these crazy, twisted hunks of metal and called them the Treasures of War. And the more pieces of shrapnel you picked up, and the bigger, the more the other kids envied you. We found some real beauties too—big knife-sized hunks with jagged edges that could cut a man right in two, whole perfect nose cones with all the rest blown away, sometimes strange pieces we could only guess at and that would always remain a mystery. We turned them over and over in our hands and just speculated.

But the best of all fell on my birthday. Me and Polecat found this hole behind my shanty and dug up an entire perfect dud. All in one piece. Black and sleek and deadly-looking as any cobra. Still hot from being fired off and whizzing down like death through the air. We cleaned it up good and carried it nice and easy over to the Colonel.

"What the hell you got?" the Colonel said. "Be mighty careful there, boys."

"Can you get the explosive out?" I asked him, but he didn't look too pleased with the idea.

"Why in the name of Jesus would I want to do any such fool thing?" He was standing in the doorway of his shanty and it didn't look like he was ready to invite us in just yet.

"This is a whole shell," Polecat chimed in.

"Yeah," I said. "It's priceless!"

"It looks a whole lot more like it's intent on doing harm," the Colonel said. But we kept after him and after him and finally we wore him down. "I'm only doing this if you swear to fetch my meals for a week," he said. That was slave labor, standing in line a whole half-hour with an extra dinner pail, but it was worth it.

We operated on that shell down by the Colonel's air raid shelter. It was in the back and out of view of the Japs. The Colonel sat cross-legged on the ground with a towel across his lap. First he just looked at it a long time like he was trying to peer inside. Then he attacked it real careful with a screwdriver and a pair of pliers, but mostly just twisting with his hands. He made us stand back so we wouldn't all die at once. He kept talking to the shell like it was his child. "Easy does it, baby. Be nice."

"How you know how to do that?" I asked. "You done it before?" It did seem a little funny, his putting it right in his lap like that.

"You hang around these islands, boy, you learn plenty about munitions. Setting a charge, handling a fuse. Where the detonator goes." He was sweating plenty, but appeared to enjoy it. "Be nice, baby," he kept saying.

"Is it Yank or Jap?" Polecat asked.

"Jap," the Colonel said. He could tell because the threads were backwards when he unscrewed the cap. And there was this tiny symbol stamped in the metal way down on the side. After he took it apart, he boiled out the powder over his charcoal stove, cleaned it up good inside and dried it so it wouldn't rust. "We could use some oil," he said. "But I guess we'll just have to wait for that."

It was always nice and comfortable in the Colonel's shanty. Some of his banana trees'd survived and they shaded the front. We all sat back and just admired our souvenir.

"How long you think before it'll be over?" I asked him. He always had opinions on such things.

"They better not take too long or there won't be none of us here to greet 'em."

"Japs'll throw up their hands pretty soon," Polecat offered up. But the Colonel looked doubtful.

"There's no doubt the Yanks got these Japs where they want 'em. They got 'em in a bear hug and they're ready to squeeze. Every sign says the Jap is a goner and that sounds promising. There's just one little hitch. The more they squeeze, the more the Japs squeeze us. It does put you and me in a precarious position, boys. Mighty precarious." That put a wrinkle in it we might not have been studying. The Colonel was of the opinion that bushido wouldn't allow certain Japs like Abiko to give up all that easy. "I'd say the best policy for you boys right now is to lay low. Layin' low is definitely the best way to keep your scalp."

But laying low was not about to be policy as long as Polecat could put in his two centavos. "Layin' Low" is what he named the little Jap plane that would only go up into the sky after the all-clear sounded. When the sky was full of bombers and fighters, thick with smoke and gunfire, heavy with hell and damnation, that little plane was nowheres to be found. But blow the all clear and allow ten minutes or so of silence, then listen careful and you'd hear him, small as a Singer Sewing Machine, circling around in the sky over Manila like he was king and would reign forever. Folks laughed every time they saw him up there. But Polecat spit on the ground and said in this loud old man's voice, "There goes your big and mighty Layin' Low." And he boomed it out so he was sure the Colonel heard him.

What Polecat wanted was to be sudden and swift. We talked about it a good bit. We figured if Dad and Harry and Southy escaped the Japs and were free, they'd be out there somewheres, acting sudden and swift. Guerrillas. Ready to pounce. "We just wait for our chance," Polecat said. "Then we be sudden and swift." And not too long after that I got a real clear view of just what this sudden and swift thing looked like. It happened when we were out in the big field and nothing over us but blue sky. Not one cloud, just sky.

It came like a dream all packaged with a beginning, middle and end. Three planes—bam! bam! bam! They were there before we saw them coming, like they just jumped the wall, moving fast. Corsairs. Bent gull wings, gray-blue, a white star, so tight and low to the trees I could see the pilots in the cockpits. Then they banked and lifted and rolled, like birds playing games.

"Jees!" I said. "You see that pilot. He waved!"

"Victory Roll," Polecat was yelling over the roar, pointing. The Corsairs climbed and rolled quick against the sun.

"He waved, for Christ sake! He waved at us!" I felt dizzy, like I was up in the cockpit with that pilot, flying fast over the trees. Then they banked again and dove, strafing something right out beyond the wall.

We were running along after them as fast as we could go, shouting at the top of our lungs, like we were trying to lift off and fly with them, when something funny happened. All of a sudden the starch went out of my legs and I dropped like a rock. The ground just came up and hit me. Whap! My heart was pounding and I was gasping for air like a guppy out of water. Boy, I felt light-headed and weak. And stupid too. Polecat was looking down at me from out of the sky like a black shadow.

"You OK?" he was asking. It was kind of flat and shiny behind him.

"OK," I was saying. "OK. Did you see that guy wave?" I couldn't get off the guy in the cockpit. "It was something, I swear."

"Sudden," Polecat said, making his hand dive and bank like a fighter. Then he was laughing, reaching out his hand to help me up.

"Swift," I laughed back at him and grabbed hold. Then I was OK again. It sure wasn't easy keeping up with Polecat. But there was no way I was going to let him think I'd gone soft. "Boy, I was flying! Did you see me flying?" I asked him, with my arms stretched way out like wings. "Or you too busy watchin' the other guys?" He looked back at me like I'd gone funny on him. And just then, while I had him off balance, I tripped him up, kicking his heels together from behind. Then I fell on top of him hard. "Maybe you missed my flying, kiddo," I yelled, "but you sure caught my three-point landing."

4

Well, you know how they generally proceed at your honest-to-God fireworks show. They start off tame, and just when you think this is nice but nothing special, they show you a dazzler just so you know it's worth hanging in till the end. There's a kind of rhythm to it, start small and build, then back off and build again. But sooner or later you know they've got to show you the real goods. And you can always feel it when it starts coming, like two big ones close together and then something real exciting just behind to get the heart pumping.

Some time in January, these other explosions—not bombs but something else—started up all around us, right in Manila. At first we took them to be bombs, but lots of times they were going off when nothing at all was happening up in the sky. You'd just hear this big boom and then this column of smoke would drift across a stretch of empty sky. There wouldn't be a single plane anywhere. It was a real mystery, so naturally it was followed by all kinds of crazy rumors. First we heard the Yanks had arrived in Manila, then we heard guerrillas were at work, and then we heard they were bombs after all just with some kind of delayed fuse. We heard a lot of other whoppers too, great and small. But it was the Colonel who finally came up with the answer. Only it was so strange when we heard it, we took it to be a whopper too.

"Who the hell's doin' that?" I asked right after two big explosions went off together.

"Japs," the Colonel said. He said it like it was gospel and you know when it's gospel you're not supposed to ask questions. So I came at it from a different angle. I kind of tossed out a lure.

"I thought the Yanks were supposed to be blowing up Manila this time?" I tried. "The Japs blew it up when we Americans were ruling here. Now it's our turn." But the Colonel didn't bite.

"It's Japs. They're trying to blow the whole damn thing sky high," the Colonel said. His voice was kind of old and shaky all of a sudden, not his usual loud delivery. But you could tell he wasn't joking.

"How come you know?" Polecat asked. He wasn't buying anything the Colonel was saying these days. Then he got out his knife, went outside and drew a big "territory" circle on the ground. "This is Manila. Here the Japs. The Japs' job's to fight for Manila, try to keep it, not blow it up." You could tell Polecat didn't like anybody messing with his ideas.

"Stand in that circle," the Colonel said. "Go ahead, get inside." Polecat finally climbed in. "Now you look out. What do you see?" That was something Polecat could really get into. You could see him just trying to sort it out. But it took him most of a minute to catch on.

"Yanks," he said. "I see Yanks everywhere coming at me." He made big engine noises, sputtered out machine-gun fire. His hands dove and banked like dive-bombers through the air.

"Now think Jap," the Colonel said. "How does it make you feel?" Polecat knit his brow and pondered it. Then he just lit up and smiled his best Jap-hating smile.

"Like a rat in a trap!" he yelled out at us like he'd just cracked the mystery of life. So there you had it. Poor old Manila was now getting it from both sides.

And at night you could really see it. These sudden flashes of light followed by heavy blasts and then huge leaping flames. They said Japs were blowing up storage depots, oil supplies, bridges, big office buildings, just about any other thing they got their hands on. Every time one went off, somebody was there yelling in your ear what he thought it was. The night sky was lit up with it. Not just on one side, but all around. And with those fires that kept burning bigger and stronger came these huge sparks floating over us, carried by the winds—some of them a couple of feet across—and it panicked the folks down where the huts were thickest in Shanty Town. Everybody was running to the ditch behind us to grab a bucket of water just in case a spark landed on his nipa palm roof. I put our bucket out on the back step, just in case.

Then I caught this glimpse of my mom in the shanty. She was leaning on the front rail, looking out at the sky like it was Judgment Day. The fires were doing funny things with her face and hair, all red and orange, shadow and light. All of a sudden she looked so skinny and frail, like a ghost that kind of flaps and shakes in the dark and won't stand still. It gave me the willies just to look at her. I think if I'd reached out and touched her just then I might've bawled. Thank God Polecat came by. I looked down and he was standing there with a bucket in his hand, all sweaty and shiny in that crazy light.

"Hello, we've got our own private fire brigade," Mom said to him. She gave him this big smile and welcomed him like Filipinos do. "Mabuhay."

"I help build this shanty," he yelled back. "Nobody's going to burn it down." And you know, I'm ashamed to say it, but it made me feel jealous. A whole crowd was standing out there on the path, looking at the sparks flying over the big field. The light shifted and rippled across them, like wind playing over tall grass. Seemed like Polecat was out there performing to the audience.

"OK," I yelled back at him. "You just watch the front. I'll cover the back." We were like little brats fighting over the same toy. It made me feel rotten. I know Dad would've bawled me out if he'd been there. It's a good thing Polecat and me never got tested. We probably would've been wrestling over who got to throw the first bucket on the fire. But the only fires were back in a few shanties and the folks there worked together, getting water on the nipa roofs before too much was lost.

Well, if that was Judgment Day, the next week was trying hard for the Resurrection. Nothing at all cooled down except when it rained. And everybody kept adding fuel to that fire with more rumors. Then some whole new kinds of lights started flickering and flashing up north across the horizon. And they kept up all night long.

"What you figure they're bombing up there?" I was asking the Colonel.

"They ain't bombing nothing," the Colonel said. He sat there real still, like the oracle studying for signs, squinting at those flashes long and hard. "That there's artillery, boy. Big guns."

"You sure?" I asked.

"Look careful," he said. "See what's different about them?" Boy, I felt ignorant. A flash pretty much looked like a flash to me. But I had to answer something.

"Not so big," I ventured.

"That's just distance. But you look out there long enough, you'll see they're all sticking low in the sky, little happening above. And most important, they keep repeating themselves. You see, they're setting there, not flying all around. Just doing what they was built for—old lock and load." Sometimes I figured there was more to that Colonel than you could find in a whole library. "That means the enemy's being engaged on the ground, boy. The Yanks is right here on Luzon and pushing south."

Well, that was a tune we'd all been waiting to dance to. I tell you, it was crackling—the Japs going crazy with the dynamite, the Yanks going nuts with the bombs, and now the twenty-four hour artillery drill. It was enough just trying to juggle it all in your head at one time. And it did seem, if they were that close, even the old codgers could hold out a few more days. But the food just kept getting scarcer and the deaths kept right on piling up—some twenty in a week by the end of January. I think every grown man had the beriberi by now, and the Colonel was starting to hobble around in earnest like he was in some real pain.

Just to show you how things had got, the Camp Doc and the Camp Commandant had a row over the semantics on a death certificate. Mom told me about it. Seems the Doc allowed some of these folks had been dying of the malnutrition, but the Commandant took exception and claimed it was more likely the heart attack. And in a way he had a point, because the heart did stop, but the Doc flat refused to sign a death certificate with that as the explanation. It is curious where folks choose to draw the line. The Japs gave him a couple of days to reconsider and then they made their move and flat out won the argument. They just threw that Doc in the Camp Jail and appointed a new Doc.

The Japs were really acting nervous now, busy burning their papers and killing their livestock like they were on the eve of some great celebration, drinking themselves silly and eating their way through the slaughter house all at once. Somebody set the carabao in front of our shanty loose and this sentry jumped on and rode him hard, trying to cut his throat with a bolo knife and hang on at the same time. He must've seen a movie about the rodeo. It took over a half-hour to do for that poor beast and in the end it wasn't a bolo but a sledgehammer that did the trick. They cleaned out all the supplies in the Jap Bodega, cooking up big pots of rice and roasting themselves big hunks of pig, carabao and chicken. There was a lot of shouting and singing going on too. We figured they were working themselves up for some of that bushido stuff. Like the Colonel said, food and drink can sure help fuel the gumption.

Within a few days we heard machine-gun and rifle fire getting louder right in the north of Manila. And all the booming explosions and fires were keeping pace. One afternoon the Japs rolled in a bunch of big trucks and lined them up in front of the Education Building. Then they got busy loading on all their weapons, supplies and such. Sentries kept running back and forth along the paths, weighted down with gear. There were rumors that they might clear out without a fight, there were others that they were going to take hostages. The Japs started making announcements over the loudspeakers, telling us to come to the Education Building so they could provide us with protection.

Around dusk I stopped by the Colonel's shanty, just to be with him awhile and watch the sunset. A Manila sunset is almost always worth looking at, but with all the fires, this particular sunset was a mighty ball of red, stretched about a mile wide, like a lantern straight out of hell. The Colonel said, "Don't you be lured in by them announcements, Johnny. They got gasoline drums stored under the stairs in the Main Building. They're scared, boy. Just think, if they plan a retreat, what're they gonna do with us? You can't tell what they might be up to. And tell your mom to stay away from those Japs too." So I went back to our shanty and found Mom lying on her cot in the shadows. I didn't see her right off. She was listening to the battle and waiting for the next shoe to drop.

"That you, Johnny?" she said. "Don't go anywhere tonight. I want you close by in case there's trouble. It could get dangerous." But I was so edgy I could barely stay put. I kept thinking about my old man. Maybe he was out there right now where the machine guns were firing, out past Cemeterio del Norte. Maybe he'd be coming in tonight. I was thinking hard about just how he looked the last time I saw him, over three years ago. I kept trying to picture it, wondering if I was getting it right, if he'd still look the same. I had myself all convinced he'd be there. It was like there was no doubt at all. I wondered what he'd be doing right now if he was in Camp. Not sitting in a shanty, I bet. I was kind of vibrating all over and couldn't stop. Like I was coming down with fever and the shakes.