|

|

| Jul/Aug 2008 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Jul/Aug 2008 • Nonfiction |

"My whole life as an artist has been nothing more than a continuous struggle against reaction and the death of art."—Picasso, on Guernica

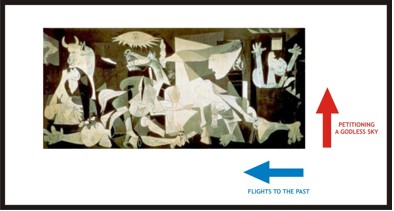

Picasso was asked repeatedly to explain the meaning behind his paintings, as though the paintings themselves were perfunctory blueprints to be rifled for their precious contents. But why attempt a canvas when an arcane treatise will do? Picasso addressed this question often, unleashing varying degrees of scorn on those with the temerity to ask for helpful captions (to which I should add—with no small amount of irony—pardon the helpful captions above.) Who could blame him? When people queried him for what he really meant, were they not asking him in effect to abandon the act of painting and become a tour-guide instead? Robert Frost's famous retort comes to mind when asked to deconstruct his art into more digestible talking points: "Would you have me say it in more or less-adequate words?" However, art is not a straw man. While perhaps helpful to us in our daily lives—for example as a way-station for interpretive reflection—it has its own reality to uphold. Moreover, the artist's recourse to imagery is a pre-reflective phenomenon, not an explicit stratagem. The latter would suggest propaganda more than art.

Subservient minds, when they petition the artist for interpretive cues, are really seeking the apt permissioning. Their own discerning powers too atrophied, perhaps too cowed, to attempt an unassisted apprehension of the art, they want to be told what is meant by the bull, the horse, the light, the arm, the baby—beyond of course what their eyes tell them they see: a bull, a horse, a light, an arm and a baby.

But irony of ironies, an artist's interrogation by an audience eager for instruction is precisely the soil within which fascism takes root. Tell us what to feel, oh Aesthetic Leader. Thus Picasso, in fulfilling his prophetic obligations, encountered the unthinkingness that Hannah Arendt identifies in her 1952 landmark book The Origins of Totalitarianism as the ingredient essential to all totalitarian societies. This is a circuitous way of saying Picasso's warnings fell on ears already deaf to prophetic remonstrance. There is a tragicomic element here as the mineshaft canary, the artist, expires magnificently, only to be trampled beneath the feet of oblivious miners.

Guernica is rich with the political symbols of its day. Indeed, the political context of the piece served only to amplify the popular clamor for bite-sized meaning. It should be said that no work of art is immune to a parochial component. To the extent Picasso's personal motives ever really mattered, they provoke at this late juncture little more than a prurient or biographical curiosity. The task of the wakeful is to universalize the artist's particularities, to drag his art through time where, if it is a truly enduring work, it will speak to us. Thus as time goes by, the artist's personal narrative becomes even less relevant. As for that odious formulation, the sanctioned interpretation, art prefers to collapse like a roof on all heads, leaving everyone to gasp for his or her own breath. Interpretation is an internal war steeped in gnostic relevance, an inward-out emanation, not a top-down command structure. What precedes and follows then are the fruits of my own struggle, lashed by necessity to a time and place other than Picasso's. How can it be otherwise?

Guernica's historical particularities still bear a contemporary relevance. In this sense, its universality has yet to be tested. (In fairness, the work is barely seventy years old.) Certainly the conflagration that engulfs the entire canvas (Orwell's perma-war) has not ceded any ground. The military milieu continues an inexorable march that, arguably, has suffered few interruptions since the Spanish Civil War, which, after all was the precursor to World War II, which after all was the genesis of the military industrial complex, the ultimate weapon of mass destruction—or is it mass economic corruption? Since then the unspoken causus belli has been an almost tautological predisposition to war. To be sure, having Johnny perennially dodge bullets keeps Johnny a malleable boy. War has the further advantage of emptying the shelves of bullets, necessitating the manufacture of ever-more deadly ones thanks to well-financed R&D efforts. Much like 1984's duteous, shifting alliances between Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia, the villains are changed to confuse the innocent. As we've seen of late, the identity of the enemy is often a troubling, second-order detail for which the powers-that-be tire of being questioned. One wonders, will they ever allow themselves to be trapped by such exactitudes again? Terror is a far more durable opponent, as it lacks a fixed address and cannot offer a definitive surrender. But for those who still prefer their wars served up with nation-states, the war drums are signaling Iran as the next deadly front. Guernica renews itself with renewed urgency. Alas, nothing has changed that would compel a fundamental altering of the canvas.

At the onset of permanent war footing, Guernica announces the "honest terror" of the modern age (Lorca's 1934 term), wherein people are driven to two wrong-directed and unthinkingly reactive modes: 1) (backwards) flights to the past and 2) (heavenwards) petitioning a godless sky. Of course these retro-modes represent futurist visions in the most superficial sense as they claim the future for the purpose only of resurrecting an idealized past.

The message drips with nihilistic despair. If war is our lot, then the future hardly warrants a mention. Indeed, one of the more striking aspects of Guernica is the utter absence of progress. The future is in full recoil from itself. Nothing is moving forward. No one, not man, woman, nor beast is evenfacing forward. When the present moment is compelled to mimic a past that can never be revisited, it becomes an inauthentic present, a toxic nostalgia. Picasso's Guernica figures are displaying, either in their heavenward beseeching of an absented god or in their attempt to light a path back to the future (the Enlightenment in retreat), a desire to, in Arendt's words "...escape from the grimness of the present into nostalgia for a still intact past, or into the anticipated oblivion of a better future." In his recent poem Guernica, Yusef Komunyakaa echoes this sense of time-collapse: "All the years/of exile bowed to him, & then time's ashes/drew past & present future perfect together."

This amnesia project is as immense as it is hopelessly escapist. The petitioning of an answerable god, particularly in its more fundamentalist permutations, must first strive to forget the indelible legacies of such giants as Nietzsche and Heidegger, just as a time-battered creationism must ignore unassailable scientific landmarks: Darwinism, the fossil record, the DNA, Dawkin's selfish gene and modern physic's fourteen-billion-light-year-old universe.

The past is lost except in weird parody. The only valid strategy is to exist authentically in the present, no matter how terrifying that present may be. One wonders what Picasso was intuiting in our future that such a wholesale retreat ensues. Auschwitz would follow, as would the killing fields of Cambodia, as would the ethnic cleansing of Yugoslavia, as would the tribal genocide in Rwanda. One shudders to think these could be mere preludes to something more terrible still.

We can blame Nazi Germany for unleashing a war of symbols in Guernica. As Russell Martin suggests in his book Picasso's War, the Luftwaffe's attack on the town represented "the first time in modern warfare that a target had been destroyed solely for symbolic reasons." So Picasso is merely moving the metaphors forward. In fact his explicit symbols symbolize the flagging symbols of culture. That's right. The symbols are, in one sense, symbolic of symbological disarray, that is, cultural inarticulateness. Culture has too often been exposed as serviceable affectation in the face of the totalitarian onslaught; flotsam and jetsam—a bull here, a sword there—being washed downstream in a powerful current of nihilistic oblivion. In a recent essay (A New Literacy," The Kenyon Review, 24:1, Winter 2007, 10-24) George Steiner noted the utter failure of culture to avert the Holocaust, indeed to coexist alongside it:

Twentieth-century barbarism sprang from within the heartland of Europe culture, from the very center of the philosophic, aesthetic, and classical education. The death camps were not built in the Gobi Desert. And when barbarism challenged, the humanities, the arts, philosophic thought proved not only largely impotent but often collaborative with despotism and massacre. The actual designation literae humaniores rang hollow.

Picasso in Guernica is depicting the holocaust that befalls culture at the hands of totalitarianism and religious fundamentalism, two forces that are often in league with one another. Would it surprise Picasso that the early years of the 21st century have been dominated by the reactionary wings of the resurgent, millennia-old Abrahamic faiths? Guernica tells us the future lies in a deep yearning for the past. What awaits us? Only time will tell.