Some artists defy categorization and do not fit neatly into a genre. Steve Augarde is such an individual. His book jacket highlights that fact—he's written and illustrated over seventy picture books for children, is a paper engineer of pop-up books, and has provided artwork and music for two BBC series. He tops that off by winning a "Smarties" medal for his book The Various.

Over the past few weeks, I had the great pleasure of conversing with Steve while he was putting the finishing touches on Winter Wood, the final book of The Touchstone Trilogy.

DD Steve, you are multifaceted in your artistic endeavours. Do you find yourself torn between mediums? Do you enjoy one over the other?

SA Yes, definitely—whichever activity I'm not currently wrestling with! At the moment I'm doing some illustration work, and so of course I'm wishing I were writing. A month ago I was writing and wishing I were paper-engineering. Next month I'm likely to be paper engineering and wishing I were drawing. Human nature.

DD Most of your writing has been geared toward children and young adults. How did you get into it?

SA I fell into it whilst at art college in the '60s. I was specializing in illustration, and every month we were given a new project to work on—a brief that was intended to reflect the kind of commissions we might find out there in the real world. Most of it was geared towards advertising. On one occasion there was a choice of projects, and one of the choices was to produce three chapter heading illustrations for Hans Anderson stories. I fancied having a go at this, and so I re-familiarized myself with tales that I hadn't read since childhood. I really enjoyed both the stories and the project. From then on, and for the first time, I could see where I might realistically be able to go in terms of a career in illustration.

I'd already begun writing, in an unfocused way, dabbling about with short stories, songs, bits of poetry. There was a half-started (adult) novel, as I recall. It seemed an obvious step to try and combine one interest with the other, and so I began putting together some children's story ideas with illustrations to accompany them. My tutors encouraged me, and I made appointments to see a few London publishers whilst I was still at college. The editors that I met were kind and helpful. They thought that I had promise, and this was enough to keep me at it. I think my first storybooks were published when I was about twenty-three—really quite dreadful stuff, twee and derivative. Mind you, in a culture where Jonathon Livingston Seagull was being seriously read by grown ups, what would you expect kid's stuff to be like?

It's still an embarrassment, though. In fact I may have to go and stick my head in the food blender for a while, just to shake the memory.

DD You were very lucky to have encountered helpful editors so early in your writing career. Which approach do you think is best for the fledgling writer—gentle criticism or the "thick skin" variety of hard rejection?

SA If you can't take criticism, and learn by it, then you're unlikely to make a good writer. But editors also need to know that you're not going to go all flakey on them and crumple under the slightest pressure. When David Fickling bought The Various he said to me, "Well, the first thing that's going to have to go is the title. Nobody will understand it."

I liked the title, argued my corner over it, and it stayed. Later David told me he'd just been testing me in order to see whether I was a pushover. I wasn't.

DD I'm glad you stood your ground. The Various is an excellent title.

Funny that you should bring up Jonathan Livingston Seagull. I haven't heard it mentioned in years. It was mandatory reading when I was in grade school. Can't remember a thing of it. I did read S. E. Hinton's That Was Then, This Is Now during the same time and I still remember scenes, character names. It is still with me after all these years. What do you think makes a story transcend time and entertain people for years?

SA The great thing about writing children's novels is that if you get it right, your work can have quite a long shelf life. As one generation passes through the targeted age group, so another one approaches. There's also the so-called "crossover" effect, where children's books are being read by adults. I don't think this is something that can be engineered, but it's a bonus when it happens. Add that to the fact that adults will often return to the books they enjoyed as a child, and you have something that could potentially be around for years. That's the nature of the beast. As to what makes a story live, I've no magic formula. But I believe it's to do with connecting, aiming for the heart. Move yourself, and you'll move others.

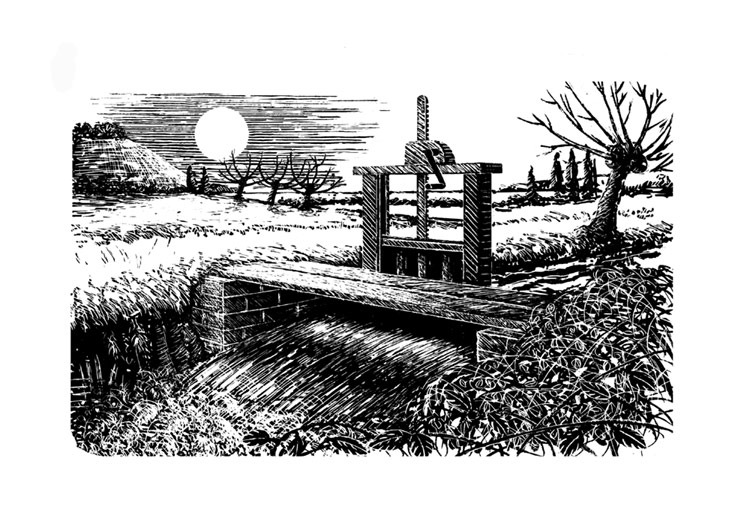

DD The covers and illustrations in The Various and Celandine, the second book in the trilogy, are beautifully moving. There's the whimsy, the cute and the scary interspersed throughout the books. Do you write with these images in mind or do they appear to you later in the process?

SA Later in the process. The idea for The Various grew around a single image—that of a girl finding a winged horse. I just had this snapshot in my head: a girl kneeling in a disused barn, chinks of light coming down through the rusty tin roof, and this thing that she'd discovered, a creature, magical yet injured in some way. It was an interesting picture, strong enough to explore.

It's about atmosphere, though, as much as imagery. If you can taste and smell and feel the environment you're reading about, as well as picture it, then you're truly transported. I like to begin with atmosphere—the smell of lavender polish on a banister, the chill of a vestry, the echo of public swimming baths. And we have the ability to conjure sensation surprisingly clearly once prompted. It's not difficult to recall the precise texture of a kiss.

So for me it's a matter of thinking beyond the merely visual. Mind you, it's easy to fall into the trap of writing overlong descriptive passages, and I've certainly been guilty of that in the past.

DD Makes one believe in the muse—for some she whispers and for others she screams—making it impossible to ignore. That image was incredibly strong and fruitful for you since it's kept you working on the trilogy for the past six years. Once Winter Wood is complete—what will you do with the characters you've created? Will we see them come back in a few years or will they rest easy in the Royal Forest?

SA I've no plans to revisit, but let's say the door has been left slightly ajar. There's always the possibility that I may go back someday.

DD I would like to talk a bit about how and where you begin a book—what is your general approach to writing?

SA If you seriously want writing to be your job, your actual living, your means of paying the mortgage and supporting your family, then you'd better write something you can sell. If you can't sell your work, then writing is not going to be your job. You simply have to think commercially as well as artistically, searching for ideas that will find an audience in an established market.

Inspiration I take as a given. Ideas are cheap. My task, as I see it, is to sift through all the driftwood that comes floating by, hang onto the bits that look interesting, and try to fashion from those something that seems truly worthwhile. But always always always with a public in mind.

Take the word "Digger," for instance. Does this seem a good starting point for a child's pop-up book? Are diggers visually interesting? Do kids like them? Do diggers lend themselves to the mechanical representation inherent in pop-up? Yes to all of these? Then test the idea out. Do a few rough drawings. Make a mock up of a couple of mechanisms. Any good? Construct a single working spread, polish it up, refine it, find ways of adding unexpected value. Then stop, and get a second opinion.

Writing something you can sell means writing something a publisher can sell, and so I try to consult with an editor at the earliest possible stage. The earliest possible stage is where enough time and thought has gone into an idea that it can be properly explained or demonstrated, yet not where so much has been invested that you can't afford to let it go.

Sometimes an editor will see a flaw so fundamental that you might as well throw the whole idea in the bin and be glad that you've wasted no more of your time or theirs. Sometimes they'll see promise, but will have suggestions for further development before they'll commit to buying. Sometimes they'll fall at your feet and call you a genius. But always they'll be looking to a potential readership, and asking the same question: "Who's going to love this? Who's going to buy this?"

I've used a pop-up book as an example here, but I apply exactly the same method to writing a novel. Actively search for ideas, filter the scraps of whimsy and poesy that come drifting through your head until you find something of solid worth, something that you can believe in—but which you also believe will have broad appeal and can therefore sell. Work up a beginning, polish it to a point where you're happy to test it on a third party. Show it to your editor and see whether they have a similar faith in it. Let them ask the question: "Who's going to love this?"

And yes, I know that you have to get to an editor before you can consult with one. But there are ways...

DD This is very helpful to those that aspire to being published. One needs to find the happy medium between what they want to write, what market would be interested, and what publisher will produce and sell it. What would you say to those with completed novels stored in boxes at the back of their closets? Should they rework their stories, wait for the trends to change, or hope for posthumous fame?

SA If you have something that's already completed, then by all means get it out there. But never adopt the scattergun approach. Try to get your work in front of one decent editor, and get an honest reaction before passing on to the next. My rule of thumb is that if three editors say "no," and for similar reasons, then you've got some serious rethinking to do. Too often writers fall for the old tale of the manuscript that was rejected on 45 occasions before being accepted. They take this to mean that if only they keep sending and sending then someday somebody will say "yes." Stop wasting your time and everybody else's. There's obviously something very wrong with what you're submitting, and if that's the case, do you really want every publisher in the land to see it? Is this first impression the one you want editors to have of you when you send in your next piece?

DD That's a healthy dose of food for thought. But—about getting the editor...

SA With regard to getting your manuscript in front of an editor in the first place, all I would say is: get permission to send. You simply have to do this. Unsolicited work is not going to be read by any major editor. How you get permission is up to you to figure out, and I'm afraid I'm not about to tip my little bag of tricks onto the table for everyone to pick over. It can be done, though, even with those publishers who say that they only accept work through literary agents.

DD Good advice for those planning to circulate their work.

Your books have a great feel for setting. I understand The Various takes place in the area where you grew up. Tell me more about it?

SA My parents were city people who grew tired of the city. They moved from Birmingham (UK) to a fairly remote part of Somerset when I was just a few months old, and for the next three years we lived in a caravan in an empty field. All my early memories are of grass, very very close up. And of insects, flowers, foxes, crows. A cart-horse called Violet. Not many images of people. Apparently my Dad used to carry me across the fields to the local pub, where he'd put me on the bar to sing "Widdecombe Fair." I don't remember this, although I do remember the chorus to "Widdecombe Fair," so it might be true. And I'm still singing in pubs, given half a chance.

When I was about four we moved from the field and onto a newly built council estate, about thirty houses surrounded by open countryside. I had to learn to interact with other children—a strange and foreign notion. But parents weren't too terrified to let their offspring out of their sight in those days, and I roamed the fields and messed about in ditches, fished the streams and skated on ponds along with other boys of my age. We were a disparate bunch—the sons of farm workers, Polish immigrants, German prisoners of war. Half-gypsy, some of them. Others, like me, had parents who aspired to middle-class respectability. We were multi-cultural before the term had been invented, and each of us brought strange snippets of language and custom to the mix. It can be very alienating for a child to never quite belong to any one solid culture or belief system, but it can also be liberating. I grew up scratched and bruised and muddy from my surroundings, the seat of my pants torn on many a barbed wire fence. And on occasion I suffered the inner wounds of childhood—the usual cruelties that children inflict on one another. But my first three years of near solitude had given me a shell to creep into whenever I needed to, a contentment with my own company that I've never lost, and a self reliance bordering on personality disorder. The Somerset countryside has been both playground and friend to me, and a natural choice to revisit in search of imaginary adventures.

DD The love you have for Somerset comes through in what you've said and also in your work. In The Various, the setting is a character in itself. The Royal Forest, the barn, Uncle Brian's property—all of it magically appears in the mind's eye as you read. Your illustrations depict the scenes beautifully.

I'd venture to say that Midge's self reliance and adventurous personality resembles that of her creator. I loved the scenes where Midge packs her lunch and takes off to explore her Uncle's property and the action that ensues. I don't know if that happens much today—partly due to safety concerns but also because children may not be interested in it anymore. Do you agree and if so—why?

SA It's a sign of the times, certainly. Today's children don't have the kind of freedom that children of my generation had. The world is perceived as being too dangerous a place to allow kids to roam about unaccompanied. Parents are even reluctant to let children walk to school by themselves. Over sensationalised media coverage is at least partly to blame. But our increased mobility is also a factor, along with the demise of the common workplace. At one time members of any community were likely to live and work closely together, and unlikely to move too far during their lifetime. The village I lived in as a child was largely self-policing. Yes, there were a couple of oddballs around, as in any community, but it was no big deal. We knew who they were.

Nowadays, with the factories and mines closed down, and the farms amalgamated and mechanized, there are no real large working communities—at least not in the UK. So people know relatively little about their neighbours. It's this climate of uncertainty that breeds wariness. We daren't let our children out of our sight because we don't trust our neighbours to look out for them.

DD Was The Various born a trilogy, or did it grow into one?

SA I was about halfway into The Various before I realized I was never going to be able to fit this story into one book. In order to give the here-and-now some credibility there needed to be a history—a past to support the unfolding events. From these details a back story grew, a story predating The Various by about 90 years. Call it a prequel, if you like. The heroine of this prequel, Celandine, is an ancestor of Midge, the modern day heroine of The Various.

I saw then that these two books would lead to a third, where the threads would converge. So the first book is set in present day. The follow up book, Celandine, goes back to the time of the First World War, 1915, and shows how the events in The Various came about. Finally, in Winter Wood, we return to present day. Probably sounds more confusing than it is.

DD I enjoyed The Various and can't wait to read the rest of the trilogy. When will Winter Wood be ready for purchase in the US and UK?

SA Winter Wood comes out in the UK in January 2008. Not sure about the States—it's usually a few months later.

DD By the way, I asked a few people at work who hail from the UK to sing me a couple of bars of "Widdecombe Fair" and not a one knew the song. You may very well be one of the few who do. Can you share the chorus here and save it from extinction?

SA What? They should be ashamed of themselves! "Widdecombe Fair" is one of the most famous of folk tunes.

Tom Pearce, Tom Pearce, lend me your grey mare,

All along, down along, out along lee,

For I wish to go to Widdecombe Fair,

Wi' Bill Brewer, Jan Stewer, Peter Gurney, Peter Davy,

Dan'l Whiddon, 'Arry 'Awk, Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all,

Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

The little Devon town of Widdecombe-in-the-Moor is still going strong, along with its fair, and several of the names mentioned in the song can be found over the churchyard wall at nearby Crediton.

DD Speaking of music, I understand you are a fan of Django Reinhardt's music. I did some research to learn about the man. How did you discover his music?

SA Ha. A long story. Let's see how much time you've got.

Music has always been a huge part of my life. I had piano lessons as a kid, and showed aptitude, but it wasn't until I picked up a guitar as a teenager that I really fell in love with playing. I so wanted to be a musician. The music scene in the UK at that time, mid sixties, was weird. There was the Beatles and the whole pop thing, but there was also a major blues revival going on—touring artists like Muddy Waters, Sonny Williamson, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGee—big names over here. We loved that stuff. And we had our own exponents of the blues: Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac, Eric Clapton, Stevie Winwood, John Mayall. The blues was everywhere.

I'd bought a National guitar, found it in a junk shop, and I listened to Blind Boy Fuller, Joseph Spence, John Lee Hooker, Big Bill Broonzy, anything I could. I learned to play a bit, and tipped up at the local folk clubs to sing a few songs. But Delta Blues? Chicago blues? I was 18 years old, English, and white. Even with the arrogance of youth, I couldn't really carry that stuff off with any conviction. So. I was a would-be musician who didn't know what to play.

Then an art college friend of mine came back from a trip to the States. He'd got hold of two albums of jug band music: one was Jim Kweskin and the other was the Georgia Jug Band. As soon as I heard jug band music, I felt at home. Here was a cheap and cheerful hotchpotch of songs that were designed to be banged out on whatever was to hand—washboards, banjos, kazoos, guitar and jug. You didn't need money, and you didn't need fancy electric instruments to play it.

And these songs were fun! "San Francisco Bay Blues," "Midnight Special," "Digging My Potatoes"—I could do this kind of thing, and enjoy it, and not feel like a complete fraud. And so could my friends. It must have taken us all of three days to get a jug band together. We called ourselves The Glad Band, and had a floating membership of anywhere between four and nine guys. Art college was a very musical place to be—it was almost a tradition—and after a while some pretty good players came out of the woodwork. One of my tutors had been at college with Viv Stanshall of the Bonzo Dog Doo-dah Band, and he brought some banjo songs into the mix. The guys who eventually became our main singer and bass player—again former art students—had also sung with Bob Kerr's Whoopee Band and The Temperance Seven.

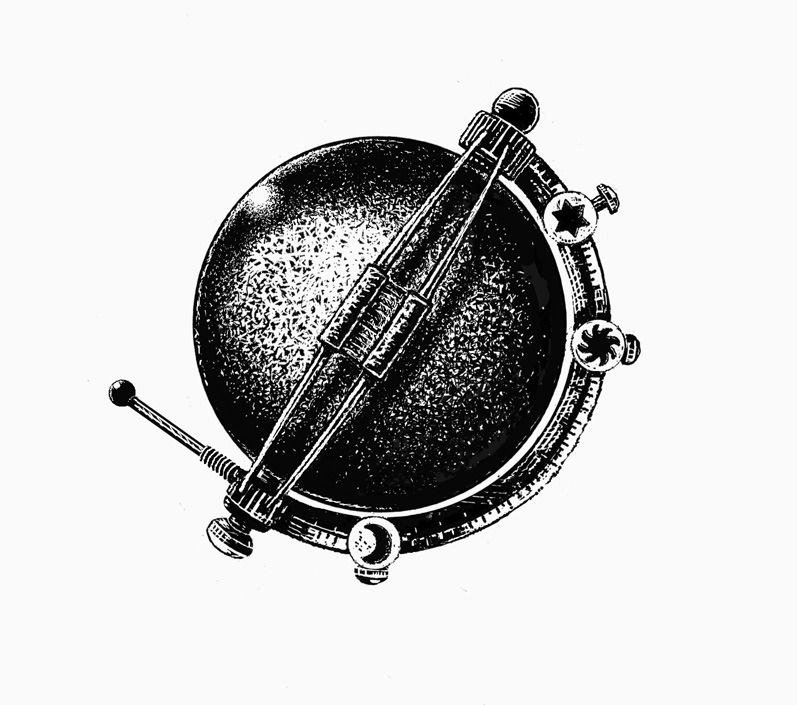

But that all happened later, and back in 1969 The Glad Band was short of material. Once we'd learned those first few songs, and played them round the clubs and pubs, what then? I had a little wind-up record player at the time—an Academy Nippy (I give this a mention in The Various). So I went down to the local junk shops and looked through their collections of 78 records, just on the off chance of finding some more of this amazing music. I picked out any songs that seemed to have a jokey or novelty title and took them home to have a listen. Some of the ones I remember are "Who Takes Care Of The Caretaker's Daughter When The Caretaker's Busy Taking Care?" and "I'm Going To Bring A Watermelon To My Girl Tonight" and "I've Never Seen A Straight Banana." I bought songs by Paul Whiteman's Rhythm Boys and The Connecticut Collegians, Fred Waring's Pennsylvanians, and Turner and Layton. I looked for anything that didn't sound English: "In Eleven More Months and Ten More Days I'll Be Out Of The Calaboose," "Dinah," "Take The 'A' Train." I bought "The Hawk Talks," thinking that it might be a novelty song about a bird.

And I bought a record called Solitude because the artist had such a funny name: Django.

You have to understand that I was totally uneducated musically, a young English art student living in an out-of-the-way West Country market town. The background noise was all Hendrix and Pink Floyd and Dylan. I knew nothing about jazz. Beyond British Trad—Kenny Ball, Acker Bilk and the like—I'd never heard any.

It was truly amazing. I honestly thought that I'd discovered jazz all by myself in those dusty junk shops. Certainly nobody around me could tell me much about it. The first time I listened to Django Rheinhardt and Coleman Hawkins ("The Hawk Talks") I wasn't even entirely confident that I could identify the instruments they were playing. It was music from another planet. But I immediately loved it, and still do.

After I left art college, I met other musicians, far more accomplished and knowledgeable than myself, including fellow writer and ace jazz guitarist Richard Madelin, whom I play with now. I kind of moved from jug band into jazz, and I've been playing semi-pro ever since. But The Glad Band have never officially disbanded, and forty years on we still meet up occasionally and give it a go.

Guitar remains my first instrument, and jazz my first love. I'm a half decent rhythm player, a chord man, but never progressed beyond that. Nowadays, if I'm performing, it'll usually be on double bass.

DD Can't help but chuckle at some of those titles.

You also play with a group called The Gents—how are they doing? Any big gigs coming up?

SA Yeah, the Gents are fine. We can only get together a few times a year now that I live in Yorkshire. I'll usually travel down to the West Country during the summer for a couple of gigs, and then the lads come up to Yorkshire in the autumn to play at the Marsden Jazz Festival. It means that we get no chance to rehearse, but that hanging-on-by-your-fingertips kind of performance can often bring out the best in you. And if it all goes horribly wrong, then we just get Richard to tap-dance. This will usually stun the crowd long enough for the rest of us to get to the exits ahead of the bottles.

DD So—anyone who can make it to Marsden should look up the jazz festival and come up and introduce themselves!

You're a busy guy. What projects are you working on now?

SA New book. Now that the trilogy's done, I'm free to write something completely different. And I mean completely different. I sold an idea a couple of years back, again to DFB, and so I'm just beginning to get my head around that. I'm also part way through writing a book on Leonardo da Vinci. This is a commissioned work, a book for children, that takes the form of a journal written by one of Leonardo's young apprentices. I think it'll work.

DD I've no doubt it will work.

Steve, thanks for taking the time to do this interview. You've shared some useful information and entertained along the way.

SA You're welcome, DD. Thanks for asking me.

Editor Note: Thinking about buying The Various or another book today? Please click the book cover link above. As an Amazon Associate, Eclectica Magazine earns a small percentage of qualifying purchases made after a reader clicks through to Amazon using any of our book cover links. It's a painless way to contribute to our growth and success. Thanks for the help!