A face in the public domain

Religion, along with the object of its worship, is supposed to have died at the hands of the New Scientists and philosophes of the 17th and 18th centuries. Gone, at least for thinking men and women, were the twin authorities of church and king, both of which claimed their truths from the mouth of God. But it turns out, magical thinking is alive and well. It lives on in the minds and hearts of all shades of the political spectrum, sometimes in the name of Science itself.

A few years ago, 200,000 people, characterized in the media as "ultra-Orthodox" Jews, climbed a tall hill in Israel to commemorate a rabbi of sacred memory. On their way back down, almost 50 of them died in the crush that occurred on the narrow slippery path. There are and always have been numerous Christian communities with similar beliefs about their own leaders and their unique, divinely inspired mission. When they are short-lived like the Branch Davidians, immolated in 1993, or the Jim Jones group who willingly drank poisoned Cool Aid in 1978 so as to enter the gates of paradise without having to wait for a natural death, we call them cults. If they have a history longer than a couple decades, they become sects or denominations. If they catch on in a big way, they qualify as religions.

The last time I checked, the calendar said 2023. An intellectual revolution was waged 300 years ago to liberate humankind from a thousand years of what those revolutionaries saw as superstition and primitive, non-critical thinking. We moderns live in houses equipped with high-speed Internet and flush toilets thanks to the Newtons, Voltaires, Mendelssohns, Humes, Diderots, Leibnitzes, and their intellectual colleagues throughout Europe. We have them to thank for a nation run not by kings and clerics but, on paper at least, by ordinary citizens. They encouraged us to use our minds without preconditions or limitation. They achieved what they did by dint of a courageous passion for the truth. They were not, like many of today's atheists, brought up in free-thinking environments, smugly scratching their heads at the folly of religious believers. The men and women of the Enlightenment largely came out of strict religious families and attended religious schools. Many of them had nuns and priests as close relatives. The father of the Jewish version of the Enlightenment, Moses Mendelssohn, was the son of a Torah scribe. Without him, the phrase "Orthodox Jew" would have no meaning today because there would be no Reform or Conservative—never mind "secular"—but only Orthodox Jews.

Yet in our time the word "science" has become a suspect, if not downright pernicious practice for a large part of a nation founded by some of those 18th-century revolutionaries. Tens of millions of Americans believe Evolution is just a "theory," not a well-founded, rigorously-tested explanation for life on earth. Millions believe the universe was created 5,000 years ago, and the fossils we find in rocks are not the remains of life forms that existed hundreds of millions of years ago, but were put there by God to test our faith in his sacred Word.

Some of us scoff at our credulous brethren for what we see as their blind faith in childish myth. We believe in Science with a capital-S. In fact, though, that word has come to mean to all too many something akin to what the word "God" used to mean: the ultimate source of Truth, unquestionable, timeless. It has taken on an authority only the church and the crown used to dare claim, and it has become a kind of Gnosticism.

Meanwhile, fewer and fewer among us are capable of the critical thinking that gave rise to modern physics, biology, and chemistry. Our education prepares us for the job market, not for analysis applied to hard evidence gained by careful observation. We are in that sense no better off than the well-educated men of the Middle Ages who could demonstrate in precise detail the effect of the planets on the least significant event in human affairs, or could calculate to the ounce the amount of gold that lay under the earth, placed there by the Creator at the dawn of time in order to provide for all of humankind's economic needs.

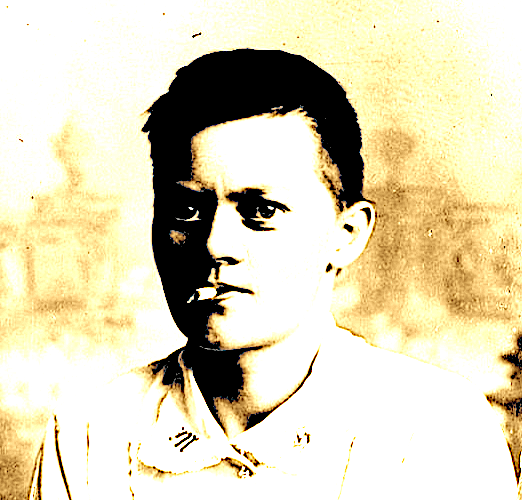

David Ben Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, was willing to accommodate the demands of ultra-Orthodox religious Jews because he thought that sort of thing would soon wither away. Jefferson and Madison probably thought the same way about Christianity, just as they believed slavery, an embarrassment to their professions of universal rights, would disappear in a generation or two. Yet in the next half century the number of slaves in the nation grew exponentially, and throughout the short history of the state of Israel, few governments have been formed without including its growing Orthodox parties, despite the general population's secularism.

Israel considers itself a modern European nation surrounded by barbarians. Yet those modern European nations Israel imagines itself to belong among have cities where an unchaperoned woman cannot walk its streets, never mind reside in, without being sexually molested. And in those same modern European nations girls of 12 have their clitorises cut out and their vaginas sewn shut to insure their virginity.

In the United States of America, a popular Christian book on child-rearing encourages parents to vigorously beat children who misbehave in order to drive out the devil that has dominion over their souls as the result of Original Sin. Those same parents are encouraged as good Christians to then embrace their children and assure them they are loved.

The refusal of a large part of the American population to accept even a probability of the effect of human activity on global warming, or the reality of climate change itself, is just one of the attitudes deriving from a mentality that has never accepted the dethroning of church and throne. It dismisses the conclusions of a near-consensus of the world's scientists that the earth has warmed significantly in the last 200 years and that gases emitted by human activity are critical to the point of affecting the planet as a viable place to live.

Most of us don't have direct access to the full evidence for phenomena like global warming or the ability to interpret them. We can familiarize ourselves with the history of fluctuations in the earth's temperature and the effect of the sun's own variations on it. We can investigate data that tabulate the tons of carbon dioxide, methane and other "greenhouse" emissions humans have put into the atmosphere since the start of the industrial revolution. But in the end we have to rely on the testimony of specialists, and even at the highest levels of such investigation, the most that can ever be asserted is a degree of probability.

But that's what science is about: degrees of probability, not certitude. There is plenty of reason to believe the earth is round and it turns on its axis, even though it appears it remains stable and the sun and stars revolve around it. I'm not as certain about that as I am about a stone falling if I drop it. My senses tell me the sun revolves around the earth. What I have for believing otherwise—testable probability—has stood up pretty well, though.

The value of scientific truth is not diminished if we admit it is tentative. Limitation is at the heart of science and what distinguishes it from authority-based thought. A skeptical, show-me attitude is science's hard-won glory, not its failing. If its truth is defined by the scope and limits of human understanding, we can freely test those limits rather than give up because our knowledge will never be perfect or because some mysteries, like human fate itself, are in the hands of a Higher Power whose will we would do well simply to submit to.

Still, the danger in accepting the testimony of any kind of expert lies in the amount of blind faith we place in them, especially in those who speak with an authority formerly reserved to the clergy and monarchs. In the early part of the 20th century, scientists who enjoyed great prestige both in America and abroad were invited to testify before Congress that the superior Anglo-Saxon race was being threatened with extinction by the infusion of lesser breeds pouring into the country. Their answer to this existential menace was eugenics, the science of "breeding well," i.e., making more white, Anglo-Saxon babies (Irish, Italians and Russians were not yet "white") and keeping out of the country races who produced inferior offspring. In 1924 Congress passed the Immigration Act, pegging immigration quotas to the census numbers of 1890. Many states set up sterilization programs for undesirables whose families chronically produced criminals, alcoholics, idiots (a medical term in those days), the insane. One respected eugenicist came up with a prototype for a portable gas chamber that could be used to painlessly end the lives of substandard humans. California alone sterilized 30,000 people. The Immigration Act remained law until 1965, when the nation was still more than 80 percent White.

Eugenics was based on faulty data, mostly interviews conducted with "deviant" members of the population about family histories, interpreted in terms of genetic determinism—"bad blood." Its main method was statistical analysis, a scientific tool then just coming into its own. The authority of what seemed cutting-edge science combined with the existential fears of a ruling class claiming a superior, white ancestry, produced more than a race theory; eugenics was a movement that spread from the US and the UK to continental Europe, where the Nazis brought it to its logical conclusion. As late as the mid-1930s, American eugenicists were still sharing their expertise with their Nazi counterparts.

Eugenics should be a cautionary tale for those who believe our freedom to reason independently of political and moral authority is a precious and hard-won right... but not one requiring constant vigilance and skepticism. An academic pedigree does not protect someone from presenting scientific evidence as dogma. Hubris is built into human nature, regardless of education or social status. Uncertainty goes against our nature. We are innately equipped to assess a danger as accurately as we can and then to act, usually without the luxury of much delay. Appealing to either a supernatural authority or an infallible "science" may give us temporary comfort, but it is a misuse of our intelligence.

At the heart of the political differences among us today are two faiths, both of which are false when they claim supreme authority. The faith of most climate-change deniers is rooted in a conviction the universe is in the control of a will or of forces inevitable, superhuman, or just pointless to resist. It's a position seemingly held by people without any religious belief as much as by those who trust in a divinity. They resist the findings of empirical investigation with the argument that its conclusions are bad science. Many of them don't bother to make a distinction between the evidence for global warming and the role of human activity increasing it. But what gets lost in the intransigence of climate-change denial is the essential scientific skepticism climate-change deniers claim to be representing. Rejection of evidence is not skepticism, it's prejudgment, an attitude promoting dogmatic, Inquisitional, faith-based mentality.

In the 1920s, opposition to the eugenics movement came largely not from prominent liberals and progressives but from Roman Catholics, Orthodox Jews, and Evangelical Protestants. Theodore Roosevelt, Oliver Wendel Holmes, Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, Margaret Sanger, even W.E.B. Dubois, along with a long list of iconic "progressive" figures, endorsed it enthusiastically. The opposition of the major religions to it was, presumably, based on moral grounds, not because those denominations had access to better science or because they had more native intelligence than the best minds of the day (though Catholics and Jews also had reason to oppose eugenics because so many of the barred immigrants were of their own faith). They turned out to be right, though, because eugenics was in fact bad science. Yet, those were the same religions that had held much of the world in a thrall of ignorance for more than a thousand years.

The history of the eugenics movement should provide a cautionary tale for those who blindly believe whatever is presented to them in the name of science. Those who show contempt for anyone who questions the evidence for global warming or the serious consequences it will have for life on the planet present mirror images of the mentality they are so dismissive of in the deniers themselves. Arrogant disdain for what is seen as medieval thinking hardly worthy of a response can be just as dangerous as wholesale science-denial based on willful ignorance. Though it can be demonstrated how much the earth has warmed in the last century, no one knows for sure how much it will go on doing so. The latest recalibration reduced that prospect by a significant amount, though not by enough to avert the consequences we are already seeing in the rise of ocean levels and other disastrous effects of warming all around the world.

When there is no room left for dialog between science-deniers and science-on-faith, the truth gets lost in the noise of a denominational shouting match. An issue like the future of human life on the planet is too important to leave to politicians who pretend to believe whatever is necessary for them to get elected. And the fate of the planet is certainly too important to leave in the hands of those who claim to speak for a divine will. But appealing to a nebulous superpower of our own making is just as feckless.

We humans have an ingrained aversion to the tentative and the uncertain. We look upon indecision—not just lack of thought but keeping an open, skeptical mind—as weakness, rather than as an attitude of humility before the great complexity of existence. If we can't accept we have nothing but our selves to rely on, no parent-figure in the sky and no formulae set in scientific stone for all eternity, we are doomed to more ignorance of the kind it took us so long to emerge from, along with consequences we may not be able to live with.