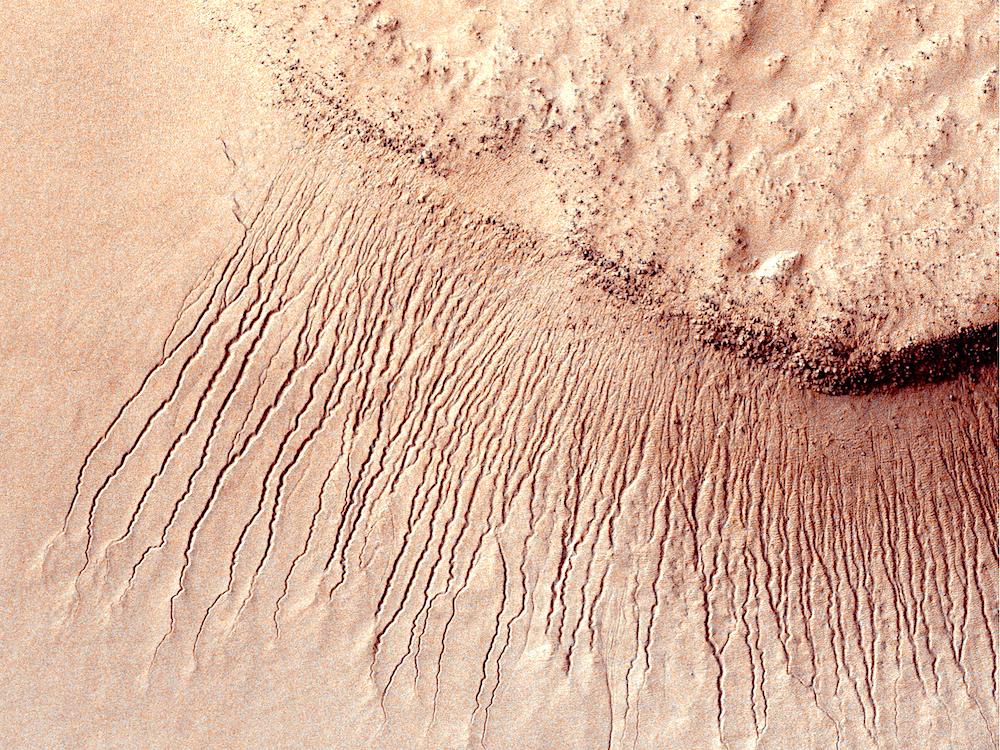

Photo courtesy of NASA's image library

The history of a nation is its national myth, the story it tells itself about who it is and why. The role of historians is to create and reinforce that myth.

This isn't to say the myth or story is a complete fabrication. But history is not a science; it cannot run experiments to verify its conclusions. Historians, the best of them, do rely on facts and an empirical approach. Even so, a professional consensus is maintained about what the national story is, the biography of a nation, people, or civilization. That narrative is true to the extent any biography may be, even those we fashion for ourselves individually, editing and enhancing as we go along. We pass on that autobiographical narrative to people in our lives in bits and pieces until they have what seems a plausible story about who we are. We do so for various reasons, any one of which may be more important than the truth of the narrative itself, which even we may stop doubting after enough repetitions.

Historians are supposed to be more careful than we are about our individual life stories, but they are no less prejudiced. They may have no official constraints on the content of their work, but an inclination to tell the most flattering and edifying tale is built in to the profession. But the historian's job is to make sure not just that the young but everyone in a society is exposed to the approved version without too much variation. Founding myths about a nation are necessarily created after the fact. First you cobble together a political entity by force and clever political maneuvering. Then you declare it a nation and provide it with a history demonstrating the people who live within its boundaries have a common identity based on deep ancestry and mutual consent. You can spin the myth in various ways at different times to suit the changing requirements of the times. France is a social contract that includes all its citizens of all origins on an equal basis; America is a land of immigrants based on the idea of God-given equality of natural rights. In 21st-century America there are competing national myths: America was founded as a Christian nation vs. America is the brain-child of the 18th-century secular Enlightenment; America is a people that wants all human beings to be free like them vs. America is an empire that engages in the same atrocious behavior as all other empires.

Differing versions of what happened on January 6th, 2021, and why it occurred have exposed the contradictions in the narrative our history textbooks used to be so confident about. Millions of Americans view the acts of that day as sedition, an attempt to subvert by intimidation and violence the constitutional process of electing a president. Other millions insist it was an attempt to put to rights a criminal disregard of the people's will. For the former, the then-sitting president's refusal to accept the outcome of the November 2020 election and the violent protest that occurred on January 6th, 2021, were violations of its most sacred law. For the latter, that cold winter day was an act of supreme patriotism grounded in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence.

Not by accident, some of the protesters on January 6th carried Confederate flags. The Confederacy from the South's point of view was of a piece with the spirit of the Revolution: a people's right to take up arms against a tyrannical government. The rebelling states in 1860-61 also claimed justification from a Constitution favoring the rights of states over the central government and guaranteeing the sanctity of private property (slaves).

The debate over slavery and states rights in mid-19th-century America was decided by a war, which cost the lives of three quarters of a million men. And then, before the nation could be fully reunited, the divide between North and South reopened thanks to the Union's failure to remain an occupying power in the South long enough to rid it of the power structure that had detached the rebelling states from the rest of the nation. It was as if after the second world war the Allies, instead of installing new democratic institutions, had occupied Europe only for a year or two and left without dismantling the political structures of fascism.

In his book The Nation that Never Was, Kermit Roosevelt (great, great grandson of Theodore Roosevelt and a professor of Law at the University of Pennsylvania) makes the argument the Confederate South did not misread the words of the Declaration or the Constitution. Both those documents assume the institution of slavery, which Roosevelt sees at the heart of the original foundation of the nation. It took a radical, new idea of the nation's social contract realized by a civil war and fundamentally reconstituted by the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to effect the "rebirth of a nation" announced by Abraham Lincoln in his Gettysburg Address. By that re-founding we adopted what amounts to a Second Constitution based on values of true equality and justice for all.

Yet both of today's political philosophies, liberal and conservative, Roosevelt argues, still base their ideological claims on the original documents of the Founders, according it, in the words of Thomas Jefferson in his later years, an undue "sanctimonious reverence." Conservatives insist on a strict "originalist" adherence to the words of the document written in Philadelphia in 1787. Liberals take "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal," as a manifesto for the political equality of all human beings, though it's clear in the Declaration its author did not mean to include slaves (slavery was legal in all 13 colonies), Indians ("vicious savages") and other outsiders. Rights were only "inalienable" (meaning, impossible to give up or give away) for some white men. To emphasize the point, the 1790 Naturalization Act specifically limited citizenship to free whites. The Declaration, Roosevelt writes, was a statement of separation from Britain, not an assertion of universal human rights such as was put forth in the French revolution's Rights of Man.

The purpose of the original Constitution was primarily to "form a more perfect union." It aimed to do so by replacing the Articles of Confederation, which had allowed maximum liberty to each of the 13 original nation-states, by adding legal machinery to provide for a common defense (based on state militias), mandatory taxation, a common currency, and regulation of interstate commerce.

In most parts of the world, the word "state" still means a stand-alone, self-governing, autonomous entity—France, Germany, Japan. The 13 former colonies were very jealous of their independent, ultra-democratic institutions and resisted the imposition of even a moderate federal authority over them. Under the Articles of Confederation, their state assemblies represented ordinary people much more directly than the proposed House of Representatives. Ratification of the Constitution was a hard sell requiring the support of many of the iconic figures of the revolutionary period—Washington, Franklin, et al.—as well as wholesale cooption of the mass media (newspapers, pamphlets). The pro-Constitution campaign's main selling point was not the document itself but that to reject it would be a slap in the face to the heroes of the Revolution and Founders who were portrayed as agents of the divine will.

This reluctance by the states to cede their individual autonomies is why the Constitution speaks of what the Congress "shall make no law" regarding rather than asserting prescriptive diktats beyond the minimum reserved to a federal government. It's also a document of compromise between the North (commerce and farming) and the South (production of commodities—tobacco, sugar, rice and, later, cotton)—with the final weight of the text decidedly in favor of the wealthier South.

Thanks to the preferential treatment accorded the South in the 1787 constitution, the Presidency and the Supreme Court were controlled by Southerners well into the 19th century. Seven of the first nine presidents were from Southern states, a majority of the first Supreme Court justices, and the apportionment of seats in Congress counting slaves as 3/5s persons (but not citizens) to enhance Southern representation guaranteed an equal balance between North and South. The United States of America—understood as a plural noun until Lincoln's time—was a divided country from the beginning.

What happened thanks to the Civil War and the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments—only passed because the states of the Confederacy were dissolved as political entities and then reconstituted under a military occupation—amounted to a rewriting of the original constitution. It required the adoption of what the author Roosevelt calls the Second or Reconstruction Constitution, though the pretense the original and its twin founding document, the Declaration of Independence, were still the guiding ones, was maintained even by Lincoln and continues today to be assumed at all points on the political spectrum.

But the rights and freedoms we live by derive from that Second Constitution, which overrode the hands-off, exclusionary theory of government ratified in 1789. The 13th Amendment, outlawing slavery, a form of private property held inviolate by the Founders, replaces both the letter and the spirit of the 1787 Constitution, which also guarantees the rights of slave owners to retrieve their human property if they run away to another state. And the 14th Amendment did not just give former slaves the right to vote (a right till then jealously held by the states themselves). It overturned the basic assumptions and purposes of the original Constitution and restructured American society. Those amendments amount to a new social contract replacing the one agreed to in the previous century.

This new narrative of who we are and how we got here is, Roosevelt admits, hard for us to recognize. We identify not just as a society but as individuals with what we believe to be the rights and obligations of the original Constitution. Perhaps just as unsettling is the reason why a Second Constitution came about. In order to win a war with the seceding states, the Union army and navy had to enlist the help of 200,000 former slaves and another 100,000-200,000 in supporting roles. Ever since Roman times, non-citizens who served as soldiers have been granted citizenship and land. After a victory largely gained through their sacrifice, those enslaved men and women who made possible the Union victory could not be reduced to the status of aliens. That meant recognizing them as full citizens with the protection such status grants under the law, the same law that later recognized women as full citizens as well as other expanded rights that could not be foreseen in 1865 anymore than the events of 1865 could be foreseen in 1787.

That new social contract should have replaced the First Constitution in our national consciousness as the recognized source of our most sacred freedoms. But we continue to insist on arguing about the "original intent" of the 1787 document instead of acknowledging the "rebirth of the nation" Lincoln proclaimed at Gettysburg. Ignoring that new, Second Constitution and sticking to a national narrative out of date since the days of the Civil War is tearing the nation apart.

The abortion issue, whether you look to Roe v. Wade or the recent decision throwing the issue back to the states, is a good example of the confusion arising when we try to find all our rights and freedoms in the Constitution of 1787-89 that just aren't there. Abortion has been practiced for as long as there have been written records and surely long before that. (It's taken for granted in the plot of a novel written in the second century.) Jefferson believed American Indians practiced pharmaceutical abortion to keep their populations at manageable levels. But the 1973 Supreme Court that found abortion to be a constitutional right based its decision on not much more than wishful thinking. Even legal experts who welcomed Roe v. Wade admit it was bad law.

The 2022 Dobbs decision is no better law, but not just because the original constitution has nothing to say about abortion. To interpret what the First Constitution does say about a citizen's right to privacy as a woman's right to control her own body—in a document ratified when women's status was not much higher than that of a slave—is not credible. But no one today would say a woman does not have as many rights as a man does, however much they may differ about the legal status of a fetus. That's because women's equality was implicitly acknowledged by the Reconstruction Constitution, even if it wasn't formulated as such until 1920. If abortion is a right, that's not because of what was agreed to in the document written in 1787, but because of the "new nation" declared in the Gettysburg Address and fleshed out in the amendments of Reconstruction. To stick to the original document as the canonical "law of the land," the only go-to authority for virtually all public issues, is to concede the high ground to the slaveholders of the Confederacy and their contemporary champions.

It's not easy to give up a long-standing national narrative for a different one, even if the benefits in doing so could help reunify a dangerously divided citizenry. National myths are like family stories handed down from generation to generation. My own family's is also a tale about a Founder. It goes like this: Martin, the patriarch, entered the country after "jumping ship" in Canada from the British navy at the end of the 19th century. Being Irish, that act was not desertion but defiance of an empire that had oppressed his people for six centuries. Only when I was into middle age did a cousin set the record straight: Three brothers traveled together to Canada. Two of them assumed an alias and walked across the border into New England. My grandfather was not a freedom fighter. He was an illegal alien.

This revised narrative pleases me more than the first, told me by my mother when I was a young child. If I were sufficiently exercised about migrants crossing our Mexican border, though, I might find my cousin's updated version inconvenient. As it is, I gladly tell anyone who is complaining about the "illegals" entering the country that I owe my existence to one of those illegals. Maybe I should be deported?

But what if my family story had been like this: the family Founder stole identity papers from an American tourist in Canada, emptied out the man's bank account, and then paid a trafficker to get him a berth on a ship headed for New York. Not so uplifting, but a tale I would have no right denying, especially if the descendants of the man Grandpa mugged are demanding I make amends.

Not that long ago, we were all on the same page of the same story. It was taught the same way in our schools and presented to us uniformly in the movies, on TV and radio and other media. Images of American soldiers heroically slaughtering Indians were displayed on the walls of elementary-grade classrooms. Native Americans were the rapacious savages of Jefferson's Declaration. Blacks were invisible beneficiaries of white blood spilled freely to free them from slavery. As a nation we may have made mistakes, but we have always corrected them and remained true to the spirit of our Founding Fathers.

Some of that narrative has recently been altered in minor ways. Images of the original peoples who inhabited this continent are more sympathetically portrayed, though that change comes only after a centuries-long genocide that left their numbers reduced to a small fraction of what they used to be. The situation for Americans of African descent is more problematic: governmental policies have disenfranchised them socially and economically throughout our history, not just during slavery and Jim Crow.

But even this much alteration in the national narrative has caused outrage for those who see any revision of the original myth as something close to treason. We are a nation divided between those who take that original Constitution as the last word, and those who, usually without realizing it, believe in a more inclusive social contract that replaced the original one almost four decades later. Neither side recognizes, in order to embrace the values we assume today, including equality for all before the law, we have to recognize the primacy of a more just and inclusive national understanding not in the original document.

The 1787 Constitution failed. If it hadn't, there would have been no need to wage a war to reunify the nation. Contending versions of what constitutes that original social contract—a minimal document for 13 sovereign states saying little about how those sovereignties governed their citizens except to guarantee there never be any restriction on slavery and that an equal representation of slave states in the union be maintained—are not unique to our generation. Neither side takes into account the extent to which the United States changed between 1787 and 1863. The slave trade from Africa had been outlawed, the franchise had been extended to most free white males, and the bulk of a vast continent had been opened up to settlement and statehood. The social contract had to change with the times or die. Only a civil war kept the nation together, at least long enough to amend the original Constitution in fundamental ways amounting to creating a new one. Like it or not, we have since the Civil War lived by the tenets of the Reconstruction Constitution, though we continue to believe the rights we take for granted derive from the one ratified in 1789.

Supreme Court decisions at different times have swung from one fundamental understanding of the national narrative to another. The Dred Scott decision accurately reads the original document as guaranteeing the right of private property in the form of runaway slaves. Plessey vs. Ferguson later acknowledged the right of states to segregate. Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 denies the right of a state to run a segregated educational system. More recently, the Court overturned its own 1973 finding that a woman has a constitutional right to an abortion, returning that authority to the individual states.

What would a national narrative acknowledging the principles put forth in the Second Constitution look like? For starters, it would replace some of the idolized Founders with the architects of the Second Constitution, not just Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and other prominent actors, but also with men and women who fought long and hard to make possible and necessary the "new rebirth" of the 1860s, African Americans first and foremost.

Yet insisting on a front-row place in our history for African Americans both before and after the abolition of slavery seems counterintuitive even to the most sympathetic liberal thinking. Slavery is seen by liberals and conservatives alike as a scandal, our "original sin." Slavery also serves as an explanation, an alibi really, for the enduring disenfranchisement of African Americans to this day, ignoring their exclusion from the largess legislated exclusively for non-blacks in the 20th century, especially during the FDR administration's New Deal.

The problem with national narratives is by nature they must remain unquestioned like any other sacred texts. To doubt them is heresy and an affront to our common idea of who we are and what we stand for. Slavery and its deconstruction, we allow, can be an important, even essential part of the narrative, but surely not so great as to make the standard story we take in with our mother's milk not only false but pernicious.

We demanded a radical rethinking of a nation's identity for a Nazi Germany or a Communist Poland. We expected it from the states that seceded from the Union in 1860-61. But after seven years of Reconstruction, during which time an entirely new society was created in the South based on universal equity and justice, we allowed those states to relapse into a new version of slavery. If that relapse (known in the South as the "Redemption") had remained limited to the borders of the Confederacy, it would have been bad enough. But the nation both South and North after the Civil War was more racist than the one that preceded it, and certainly more so than the one Jefferson and Madison lived in. The post-War "one drop rule" used to determine someone's so-called race was a Northern import to the South, but a convenient one for white Southerners to maintain former slaves and their offspring in a brutal state of subservience for another century. It served the same purpose in the North, most notably in retrogressive federal, state, and local laws and policies throughout the following century.

The South may have lost the armed conflict of 1861-65, but, along with its Northern sympathizers, it managed to maintain the original, exclusive national narrative created by Jefferson and Madison instead of acknowledging the new, inclusive one proclaimed in the Gettysburg Address and expressed in the legislation passed by Congress shortly thereafter. The consequence of Southern "Redemption," a return through Jim Crow to something like the status quo ante, meant the new narrative of Gettysburg only made it into the national myth as a side story. The main characters have remained the same as those in the original myth, if anything enhanced in the public consciousness. Their statues, dressed like Romans, adorn our public buildings, secular versions of the murals adorning the Sistine Chapel and stained-glass windows of churches. Even today, as Kermit Roosevelt points out, a long-running Broadway musical called Hamilton, while it has numerous black faces on stage, has no black characters. The heroes of the revolution of the 1860s, the one waged by the Union in the name of the original constitution but in fact supplanting it, have made it into the national story only as a sidebar. Only Lincoln gets to play a leading role in the story, and that's because he's portrayed (and professed himself to be) a defender of the Constitution of 1787-89.

Recent versions of the national narrative like the New York Times's 1619 Project are viewed as radical and banned from some public school systems, though the banners hold to the official story of a nation founded on equality and justice for all as expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the original Constitution. But to suggest privilege based on skin tone, wealth, and ancestry were at the forefront of the Founders' minds is not acceptable. Yes, there have been injustices, we admit, slavery first and foremost. There has also been racism, even genocide of native peoples, but the nation has always returned to its original principles. Racists, non-racists, liberals and conservatives alike, believe our nation is founded on principles expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the original Constitution. We have only to read those documents fairly, they say, to find them.

Our inability to recognize and accept a radical change in our national story is at the heart of our current dysfunction as a nation. Even the most liberal among us are uncomfortable acknowledging any substantial change to that story. We have absorbed the standard narrative so thoroughly, anything else seems counter-intuitive, even insidious. It would take as radical a change in our public consciousness to convince us of our mistaken belief in the standard story as it took to alter the myth itself in Lincoln's day. He did not dare to change the original narrative, and perhaps he believed it himself. He called upon the words of the Declaration that "all men are created equal" to express the aspirations of a new, reborn nation. He did not declare the nation's old contract wanting, he used it to justify the legitimacy of a new one. Perhaps he had no choice but to do so, but we as heirs to his words have an obligation to acknowledge there is a basic disagreement between the document written in 1787 and the freedoms we declared when we replaced that Constitution with one radically more inclusive. Until we do acknowledge that change and alter our national story accordingly, we will not escape the culture wars we have been waging for the past century and a half—events we see on our television screens being just present-day versions of opposing and irreconcilable narratives, a house still divided against itself.