|

|

| Jul/Aug 2019 • Travel |

|

|

| Jul/Aug 2019 • Travel |

IV

For a brief moment, we are weightless. As the hill curves away below us, the speeding car we're in cuts six feet straight into the sudden sky. Gravity still craves us, the globe still pulls at us, and in a fraction of a heartbeat, we're going to slam back into the ground nose-first. Looking out the window at the rapidly approaching planet, I can't help but think: I've got a bad feeling about this.

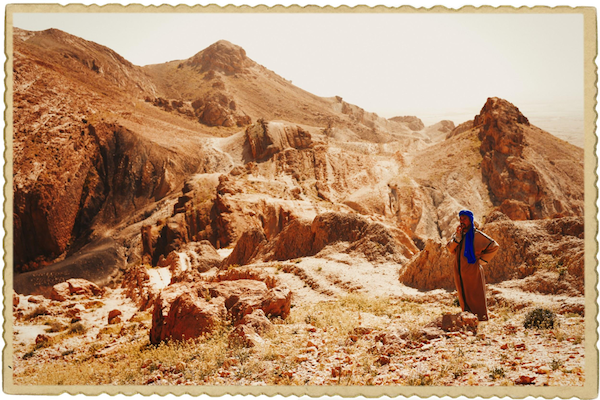

We're in Tunisia, near the Algerian border, in a finger of the Sahara that stretches up furtively toward the Mediterranean—of which there is no hint, anywhere. There are no trees, no shrubs, no flowers, just endless dunes occasionally punctuated by small puddles of delicate pink saline, stagnant but genial thanks to their strawberry hue—the gift of largely dried crystalline run-off from the Atlas Mountains.

The news cycle about Tunisia is repetitive these days—tales of terrorism, torture, bombings, religious fundamentalism, and potential rebellions. Those are, in fact, the things that have brought us here: not the horrifying real-world kind, but the charming, silver screen variety.

You see, we're here for Star Wars.

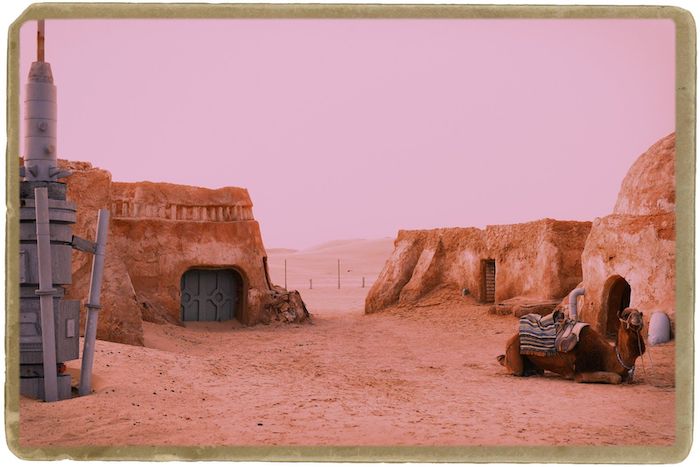

Nestled into the dunes of the Northern Sahara are the sets of several of the Star Wars films going back more than four decades; Tunisia has long been Lucasfilm's stand-in for its desert planets, and rather than suffer the expense of striking and removing them, they invariably abandon the alien villages, towns, cities, and outposts as incorruptible corpses in the dry sand, waiting patiently across the ages for fairweather friends to finally arrive.

Star Wars is, by any measure, big business; with a dozen films, several television programs, endless merchandise and now amusement parks, the futuristic franchise set a long time ago and far, far away is worth a whopping 42 billion dollars—larger than the James Bond and Harry Potter brands combined. Larger than the GDP of 107 countries, worldwide. The value of Star Wars to tourism is obvious: the best-known—and arguably most widely beloved—series of films in the world turns everything it touches to gold.

In Tunisia, though, they've chosen to put the future behind them.

I've come to this sandy, forgotten corner of the world on assignment—my editor, knowing both my love of Star Wars and its recent return to the pop culture landscape with a spate of five new films, sees it as a chance for a story. I, having no sense of responsibility of any kind, pack a bag the next evening and prepare to board the four planes, three trains, and one boat separating my front door and Luke Skywalker's, just outside of the small town of Tozeur.

With urban exploration an exploding travel trend, and Star Wars a revived cultural presence, the plan is simple: I'm to go to the ruins of the old movie sets, still sleeping in the deserts, and make portraits of the many costumed cosplayers who, in the height of the current Star Wars mania, turn up every day at some of the few real-world relics of the films that inspire, and in some case shape, their lives.

In a hurry, I kiss my wife goodbye. I love you, she tells me, and seeing the opportunity, I look her in the eyes and, doing my best not-very-good Harrison Ford impression, say I know before bounding out the door, self-satisfied in my moment of triumph. Before I'm even in my taxi, my mobile phone rings, and she tells me that, fantasies of Han Solo and Princess Leia dancing in her head, she's coming with.

V

"Where are you from?" grizzly Luke Skywalker, now 40 years into his swashbuckling career, asks his new apprentice, Rey. "Nowhere," she replies, sad but defiant.

He shakes his head. "No one's from nowhere," and she shoots back the name of the desert orb where she was raised, lived, yearns to get back to. "All right, that is pretty much nowhere," he nods.

If Tozeur isn't nowhere, it's certainly next to it. The map shows it as the pinpoint outpost between two huge bodies of water, an antioasis of burnt umber in a field of cool, refreshing blue; in reality, that sea around it, the Chott el-Jerid, is a long, dry salt plain that stretches out to the horizon—and farther—ringed by a highway, the litter of abandoned buses, dusty unwheeled cars, the calcium husks of long dead camels. The name of it, Chott el-Jerid, is Arabic for "Lagoon of the Palms." There is no lagoon. There are no palms.

One can imagine the slick marketeer, no doubt first cousin once removed to the guy who came up with "Greenland," pitching it to the weary travelers just emerged over the Sahara, wiping with silk rags their furrowed brows. He'd see them first as uncertain mirages on the horizon, then growing, pecuniary opportunities. Welcome to Tozeur, he'd tell them, gesturing out at the expansive, toasted earth. It is the Lagoon of the Palms, he would tell them—the palms are just a little bit farther, he'd say, and the lagoon? Well, it's dry season. You should see it when the rains come.

A thousand years later, their grandsons and daughters wait, still, for the rain their dog-tired forebears were promised. So far inland, they've never seen a sea, an ocean, a lake, or the fields and forests that accompany them. The animals are beige, the land is beige, the homes are beige. Blue is a stranger; they don't know there is any green in the whole galaxy.

In the distance, the Atlas Mountains provide the only vague color in the landscape. They were formed in prehistoric times in the same tectonic collision between Africa and North America that formed its sisters, the Alleghenies of Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The range, which coils from Morocco to Tunis, takes its name from the Berber word adras, meaning mountain, making the entire thing the Mountain Mountains. What its name lacks in creativity, its hills lack in color: long expanses of cinnamon-toned rock with only the gentlest kisses of subtle maroons, pale pinks, old, sun-bleached yellows. A well-paved road leads from Tozeur through the mountain pass that, only an hour later, arrives in Algeria—where, the day before we land, a suicide bomber has walked into a police station adjoined to a power plant, turning out the lights in a thousand homes and, of course, himself.

Here in Tozeur, though, things are quieter—the remnants of an old, largely discarded tourism industry keep on at a low hum. The airport we land in after a 28-hour journey is small; the luggage claim has a conveyor belt that appears to have broken a decade or two back, but two polite uniformed men carry bags down the ramp and into the arrivals hall with great pomp. A small rack of brochures sheltered in an old stand between the one airport café—closed—and the one airport bathroom—closed—offers two different pamphlets. The first is full of pictures of the Red Lizard tourist train—a beautiful, restored 1940s steam locomotive that rollicks through the local canyons—showing foreigners standing inside its elaborately decorated cars, clad in white linen, looking for all the world like they're waiting for champagne cocktails or, possibly, an exceptionally elegant murder. The second has, for its cover, a photograph of Luke Skywalker.

Leafing through the Skywalker brochure on the way to the hotel, I grow more and more excited to shoot this story, to find the delightful weirdos who'd come all this way to dress up as characters from their favorite space western. The idea that this place—distant and forgotten—would win that small lottery by having a director from another continent randomly pick it so many years ago is irresistible—how did this place shape the films? How did the films shape this place? As the adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, drones out from one of Tozeur's 13 minarets, I'm watching out the window hoping to find a prologue in this void scenery, a new hope to find its characters in the unrequited, unrenowned people that the Star Wars world—and our world—left behind.

As we pull in to the hotel, Robin, a costume director for the opera, is telling me about her plans to find a local fabric shop, whip together a quick Tatooine-appropriate outfit to impress those far-flung nerds we're to meet, hustle, and hopefully photograph in just a few days. She loves this stuff and never fails to find an opportunity to show off to even the strangest of strangers. Seeing her starry-eyed in the seat next to me, I can almost picture the visions floating through her head: My goodness, they'll say, feeling her material, looking at her 30s-something face and bright red hair, you're the most convincing Rey we've ever seen. As she dreams of her cosplay homecoming, our taxi arrives at the hotel's guardpost where a small, tired man stands up, his body limber and loose, and he runs a scratched dirty mirror, strapped to an old broom, under our car. Robin snaps back from the galaxy's edge. "What's he doing?" she asks the cab driver, visibly nervous. He responds in French that he's looking for bombs. A few moments later the guard waves us through. These are not the photographers he's looking for.

Tozeur is sleepy and hot, very hot, oh so very hot, with thick air that doesn't move. Hot as an oven. Every door one opens feels like it swings out into the mouth of a giant, lazy dog. Picking up a clump of sand in my hand at midday, it's so scalding I reflexively throw it out into the middle of a street, where it dusts onto the side of a cart, confusing the driver and startling his donkey. While it's a typical desert climate at night—cold and fresh—by the time one's morning tea is finished, the mercury's risen well up over a hundred.

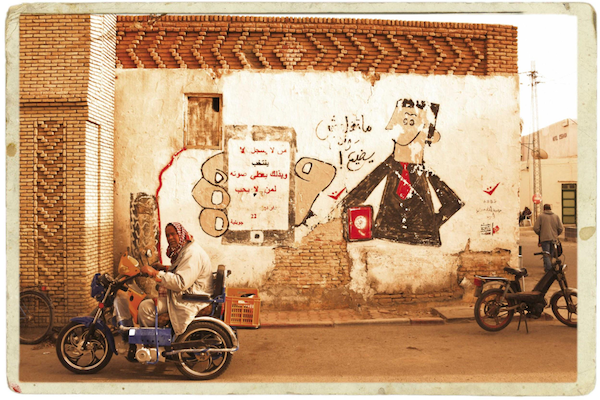

George Lucas, when making the first Star Wars film in 1976, spent weeks here before the shoot, scouting—looking for locations and, like all good artists, cribbing ideas, taking inspiration from local features, people, clothing. Obi Wan lives in the canyons to the north of the city, created as the fossil-filled floors of saltwater seas dried up millions of years ago, where plenty of isolated families and, yes, hermits still make their home. The Jawas—small, rodentine traders of sentient robotic slaves like R2D2 and C3PO—wear robes identical to the ubiquitous ones worn by every man in the Tozeur market on his way to buy rice, peppers, camel, and goat meat. Trying to put together my photo essay, I attempt to photograph them on the sly; when one catches and asks me why I'm photographing him, I struggle to think of a flattering way to tell a perfect stranger that he looks like a slave trader.

Star Wars is the first film I ever saw in a movie theater. I saw it in Italian with my grandfather, a man with whom I had little connection but who, like me now, loved the movies, the old ones especially. The world was for him still a place framed by Laurel and Hardy, and Abbott and Costello, but for that one day, also Luke and Leia. It was a hot, sunny late afternoon when we went into the theater. Decades later, I can still remember that first moment: I was six years old, stunned upright by the prompt blare of trumpets as the movie opened into a scrolling yellow text I could not read. Then space battles, scenic wayfaring, adventurism of every kind—at six, none of it seemed silly. Having always lived in cities, I couldn't believe the sight of the desert—how did they build it? Did they take all the sand from every beach for miles and put it in one place? I didn't know there was that much beige in the whole world.

On a 40-foot wide screen, ambiguous heroes and villains with lasers and swords dashed about trying to slice one another down in an otherwise unambiguous world: all scenery perfectly white or perfectly black, all people perfectly beautiful or perfectly ugly, perfectly smart or perfectly dumb. It was the biggest thing I ever saw, and we walked out of that theater, hours later, into night, him holding my hand as I looked up at the stars.

Not a single local person I spoke to in Tozeur admitted to having seen any of the films.

Nevertheless, it does seem like the end of the universe, the sort of place where one would, in fact, find quixotic heroes that always seem to pull it off. The Star Wars empire was built not on quality, one regrets to admit, but on personality—charming characters who've risen up to become archetypes, defined editions that can exist comfortably in the third person. The heroes are supposedly aliens with magical powers, framed as romantic daredevils but in function just odd-shaped demigods. The good guys are never fully good, the bad guys are never truly bad, and the greatest intrigues come from the folks who care to be neither, the opportunistic mercenaries and rebels with undefined causes.

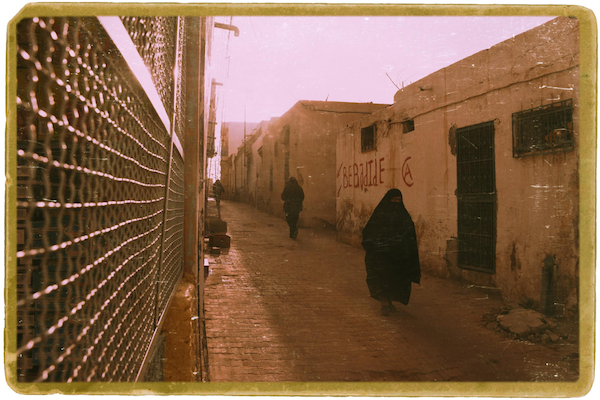

As we walk into the fabric store to slake Robin's sugar-plum fantasies of being a feminist space-champion, five men jump to action, sharks smelling fresh blood in the water, excited to meet somebody with dinars to spend and no sense of their value. At this point we're a day in, searching yearnfully for the Skywalkers in even the smallest of details in this medieval Muslim town, and as the men jostle her, I hear Robin mutter under her breath: I am one with the Force, and the Force is with me. I am one with the Force, and the Force is with me. I am one with the Force, and the Force is with me. In the souk, scammers heckle us, haggle with us, try to lure us into their homes for reasons benign and not, as women in burqas and greengrocers and bus drivers pass us without even a glance. Some people have nothing, and want nothing, and are free.

VI

On the outside of the café is an elaborate mural of a masked man killing a Jew with a meat cleaver.

After several days in Tozeur, I've yet to see a single tourist. Our hotel, a monumental poured concrete resort painted, yes, beige, was built to surround an olympic-sized pool that never quite gets to a comfortable temperature and has only four other occupants: two French businessmen there to discuss a water refining contract, and their wives, who sun themselves by the pool from dawn til dusk, waiting and wishing that the water might reach tepid. It all evens out, in the end: their tans are exceptional, and their towels remain dry.

We've seen no one, from nowhere, not in town, not in the market. Over a lunch of camel meat, we think we see an Italian—cool guy sunglasses, a certain demeanor—but are disappointed to hear him start talking to the restaurant owner in accentless Arabic. We stop to visit a mosque, whose overseer steps out to greet us, finding our presence surprising and, in fact, a bit far-fetched. We don't get many visitors, he tells us, but take off your shoes, and feel free to take a look around.

We hire a driver to take us to the ruins, assured by a local that this man will know how to reach all of them. Trying to negotiate a price—for the purposes of a photography assignment, I'll need to be out there most of the day—and with each passing minute I'm assured that the ruins are more and more, and more remote.

An hour into the drive, he stops for a cigarette and points us toward the café across the street, telling us to go and enjoy some tea and come back in a half hour, and we make our way across, trying not to look at the painting of a faceless man in a yarmulke being hacked to death on the wall. It is a punctuation mark so common to the area that it almost escapes notice—we've seen at least a dozen such murals in the last three days.

When we walk into the café, time stops.

Women are not explicitly banned from such establishments in Tunisia, but they're certainly frowned upon. Robin, wearing a long skirt, long shirt, and headscarf, has done her best to blend in, but we've still gotten small stares at every restaurant we've sat in, and as we walk into this bar an hour into the desert, the glares are far less subtle. The café is a large white room with tiled floors and ceilings and a dozen or so couches of different colors spread slapdash throughout the space; roughly 40 men sit on the couches with newspapers, smoking hookahs alone and in small groups, little plates with tea and coffee set down before them. All 40 men have snapped their conversations to an end and are staring at us. I make eye contact with two of them, both visibly red with rage, trying not to stare at us so much as through us. I am sure I can hear their thoughts: He doesn't like you, the first glares at me. I don't like you, either.

In her bag, Robin has the Rey costume she's methodically put together, which she tightens to her side. Several men shout something at the bartender, who looks uncomfortable, and they storm out angrily to who-knows-where, to do who-knows-what.

I think about just how long it takes a cab driver to smoke a half hour cigarette. Robin asks for the key to the women's bathroom and two coffees, which are placed in front of us, and are immaculate.

"That will be one and a half dinars," the bartender says to me, smiling genuinely. "One dinar for you, and one half dinar for her, for having the courage to come in here."

EPISODE VII

An hour later, our driver is careening over the sands of the desert, which he knows like my grandmother knew her garden—every hill, every valley—and he is clearly having the time of his life. We're supposedly on our way to the abandoned Star Wars sets, but he's having too much fun speeding over the hills and getting the SUV into the air and bringing it down, hard, into the dunes. One suspects the car is owned by someone else.

Every 20 minutes he stops at one café or another, to smoke this cigarette and the next and the one after, and we meet a real rogue's gallery: men selling real fake things, men selling passports. At one stop, after a particularly long airborne excursion, we meet two teenage boys who try to sell me an emaciated but still cheerful fennec fox—an adorable desert creature whose oversized ears make it capable of hearing anything for miles around, but don't give it the wisdom to know not to trust men with ropes.

When we finally arrive at the first of several Star Wars sets, it is empty. They're all empty. Anything of value was picked off long ago, and now a few bedouin types haunt around it, using the pockmarked shells of far-far-away Tatooine as lean-to shelters. We set up shop to wait for the cosplayers, who I am still convinced are coming, as we're periodically pestered by fellows trying to sell us rocks. One man has collected several Star Wars apparel items left behind over the years, which he's happy to rent out.

In our hours there, not one of the expected, eager, moon-faced intergalactic cosplayers ever turns up. We wait through the hot of the day, our driver sitting on a hilltop looking more and more bored, as absolutely anyone fails to appear, and the bedouin rock-sellers laze without any sense of any real hope.

As the sun begins to kiss the horizon, the air quickly grows colder and colder; the empty darkness of the desert is a scary place to be at night, and even the handful of dwellers here in Lucasville are beginning to set up inside the empty Skywalker homes for the night.

All of a sudden, in the distance, a small, glittering cloud appears over the horizon, heading towards us. It is kicking up a small rustle of shining silica sand but making a huge, rumbling noise that echoes and rummages through us from miles away—in the desert, all din feels like doom.

The bedouins poke their heads out of their movie set homes. For four solid minutes, we watch the enormous white bus roll through the desert; the few locals even stand up out of their layabout recline to watch it with us.

The bus pulls up, its door opens, and out come 70 Chinese tourists, wearing uniform white t-shirts and visors. They descend around us, swarming, moving as the sea moves, making pictures here and there, wordlessly and in waves, taking turns photographing the same couple buildings, over and over, the same bedouin rocksellers, over and over. After five minutes, the bus driver comes out, calls loudly to them, and they file rapidly, in a long narrow line, back aboard.

As we watch from the ruins of Tatooine, the bus zips off westward, chattering into the darkening desert, framed perfectly by the single setting sun.

Click here to see additional photos related to this story.