They hadn't found the Inca ditch, and Eric was frustrated with the directions they had been given, the rental car, the road, and, finally, himself. He had been sure they were on the right route, although it was rougher than he had expected, and the little rented Toyota was not designed for off-road driving. If Camille was disappointed, she didn't show it. Scanning the area with binoculars, she kept looking, and then raising her camera, she photographed everything. Twice she thought she had identified the ancient Inca waterway, and, indeed, she may have, but Eric couldn't see it. Instead, oddly detached, he watched himself slip deeper and deeper into a black mood. Camille could feel it, he knew, but she kept herself bright, making him stop in Nono to buy lukewarm Cokes, reading out the driving instructions early enough that he always knew what was coming, or what was supposed to be coming, but not so early he had to ask her to repeat them. It was clear she was refusing to allow him to keep her from enjoying the adventure of their trip. They had stopped at a steep overlook to peer down into the Toachi River for Torrent Ducks, and instead had been treated to good views of Andean Dippers, walking placidly into the rushing water like men in diving suits, their heads going under without ducking or flinching.

"Do you think they just keep walking like that underwater?" Camille said. "I picture them toddling along on the riverbed looking for something to eat just as if they were on land."

"They must swim," Eric said. "Wouldn't they be too buoyant to just walk along the bottom?"

"I don't know," Camille answered, relieved they were having an ordinary conversation again—ordinary for them at least. "Their feathers aren't oily, so they don't trap air. But I guess they wouldn't be able to go very deep without losing their connection with the bottom."

"Hmm," Eric said, "losing connection with the bottom. That's an expression with possibilities."

Tired, he'd almost driven past the entrance to the Hostelería La Fantasíaía La Fantasía, where they were going to stay for two days. This had been Camille's pick; she had never been there, she said, but had been hearing about it for years. In fact it was with her description of this place that the idea of their trip to Ecuador began.

"It's famous," she said, "they say there's no place like it." And, indeed, as they crept up the curving driveway in the little white car, it was like no place either of them had seen. The Posada Bavaria in Puyo had had a misplaced German feel, like a Bavarian beer garden, but this was a full blown Tyrolian chalet, surrounded with monstrously overgrown topiary. They pushed open the door, which needed a coat of paint, and were met by a dessicated woman who spoke English with a pronounced accent. An elderly man stood in the background, apparently waiting for instructions.

"They say she was a countess, a Russian countess," Camille said once they were in their bungalow.

"I make her out a Nazi," said Eric, "the wife or lover of a prominent officer, escaping late in the war when the inevitable became clear."

"Then where is he?"

"Didn't make it. He sent her over first, hoping to make his escape later, to meet her here, but he didn't make it out."

"And her accent?"

"German, not Russian. Besides, if she were trying to escape the Bolsheviks she would have come here much earlier. The guidebook says the place dates to '45."

"What if she fled first to Germany, then here?"

"Another question is how old is she? She doesn't seem in her 80s. More in her 60s or 70s."

"Okay, what about the old guy? An old family retainer, loyally serving out his years here in the tropics?"

"Or a subaltern of her husband's, sent with her to protect her, still serving the Reich in his own way."

The bungalow was clean but damp. As they were going to bed, Eric said, "Imagine never in your whole life knowing what it's like to slide between cool, crisp sheets. Never being free from this sticky humidity."

"Yes," Camille said, "but you'd never be cold, either. Not really, teeth-chattering, shivering cold."

"Right, if you ever are shivering, it means you have a fever. Probably malaria."

"You're in a good mood tonight."

"Watching you get out of your clothes is helping."

Camille smiled gently. "You like what you see, señor?" she said and struck a pose at once comical and sexy.

"I like," Eric said.

"If we make love, we'll get all sweaty."

"Then at least we'll have a good reason to be sweaty."

Later they rolled away from one another, laughing and happy. But during the night, when she reached for him, he shrugged her off in his sleep.

In the morning she awoke to find him struggling to write in his notebook. Before she was really ready to talk, he was talking to her, angry, mostly with himself apparently, but it seemed to spill over. "I can't write about this place," he said. "There's nothing to say Lowry hasn't already said. Decaying elegance is the only phrase I can think of, and it sounds right out of Under the Volcano. And Lowry never even made it this far south."

"I'm taking a shower," Camille said. "Is there still time to get breakfast?"

In the dining room Camille started photographing before their eggs were served. Eric watched her measure and weigh the light, consider angles and patterns of color. As always when she was working, she moved with the lithe grace of a big cat; she was stalking images, alert, intense but not tense, loose, completely in the moment. He envied her this ability to get totally involved in what she was doing. He knew the feeling just enough to miss it, like Salieri in Peter Shaffer's play, knowing enough of genius to recognize it in Mozart, and to recognize its lack in himself. He pushed his eggs away and poured himself more coffee.

In the afternoon they walked around the grounds, a nine hole golf course surrounded by surreal gardens, dark green bowers like grottoes. Camille was delighted by the sight of a small herd of cows grazing in the middle of an unkempt fairway, but Eric seemed to take no pleasure in it. Still less did he take pleasure in waiting for her as she shot half a roll of film of the improbable cows, black and white; "Perfect Motherwells," she called out to him. Rain surprised them at the edge of the forest, first a sound like wind in the leaves, which had seemed to be dripping softly even before this, then a crack of thunder, and they huddled under the cover of the overhanging branches to keep from getting drenched.

Camille thought wistfully of another thunderstorm, only a month before. She and Eric had been walking in the park near his house on a blisteringly hot afternoon, and suddenly a breeze came up. The cell was sweeping in from a little north of west, so the sun was still shining as the thunder cracked and the first plashy drops of rain hit. In five minutes it was as dark as late evening, and both of them were soaked through, but they were laughing, running toward Eric's house. People in cars, their windshield-wipers slashing furiously, stared out at the two of them, the wet clothes clinging to their bodies, Camille's hair sticking to her neck in tendrils.

"God, you're beautiful," Eric said when they got back to the house.

"So are you," she said, and his impulse to deny it, to see only his flaws and refuse the compliment as he usually did, that impulse, for once, died before it was fully born; she had succeeded in making him see—and believe—that he was, at least in that moment, beautiful in her eyes. And they stripped off their wet clothes, and she scampered naked up the stairs with him in pursuit, and they opened all the bedroom windows and lay on the bed, gooseflesh against gooseflesh, and warmed each other as the thunder continued to clap, and the rain clattered down, and playful, then tender, then passionate, they made love with the thrilling innocent lust of children discovering it for the first time, and in the final decrescendo, Camille found herself weeping to feel so much.

Now the rain was falling here in this enchanted garden, and the mood was funereal.

After the rain, Camille stayed out photographing, and Eric headed back to their cabin to write. Only he couldn't. He had been sitting at the small desk in the room with his notebook before him and his pen ready, but he couldn't make the words come. And there was nothing else to do. Long accustomed to living alone and used to working in his home, he had a hundred diversions to keep him from obsessing on the failure to write. But here in the steamy bungalow, there were no dishes to wash, it was not his responsibility to clean the bathroom, he could not do his own laundry. He had already showered twice, trimmed his fingernails and toenails, studied his face in the mirror, dug out his sewing kit and resewn a loose button on one of his shirts. He had shined his shoes, arranged the clothing in the drawers, and paced the perimeter of the room countless times. If he were at home, he would now be out cutting the lawn, washing the car, weeding the garden, painting the mullions of the garage windows, or even changing the oil in the car. I am unhappy, he thought, and then, finally, he began to write:

Unhappiness. Is there such a thing? Is unhappiness the opposite of happiness or simply the absence of happiness? And then what is happiness? When have I been happy? And during those brief times, what exactly did I feel? Is happiness a thing to be felt at all? Or is it unhappiness that has the characteristics of a thing—presence, palpability, duration? It is happiness that is the absence. Happiness that is the ephemeral, unreal emotion, defined only by its difference from unhappiness, alienation, skepticism, failure of hope, which are the actual, real characteristics of the human condition.

He continued in this vein for about an hour or so, pleased the words were coming, letting them come without being too critical of the content. There was always time for revising. He watched his mind as from a distance and saw it in all its brooding skepticism, its insistent hopelessness. Even the thought of Camille didn't cheer him. The only bright spot he saw was in solitude. If happiness was indeed the absence of longing, dissatisfaction, frustrated hope, disappointment, and pain, then the place to look for it was not in a relationship with another human being, for there one was bound to fail. But perhaps in solitude, with no expectations of another person, no looking forward or back, just living moment to moment, as in his garden...

When Camille came back, he was almost surprised to see her.

"If I can't write," Eric said over dinner, "I am nothing. It's my only claim to fame, the only thing that gives me that kind of satisfaction, that makes me feel I have accomplished something."

"What about your teaching?" Camille said, looking up from her soup. A young boy had served them after first serving the Countess and her companion at their private table across the room.

"Teaching doesn't do that for me. I am a writer who teaches, not a teacher who writes."

"Why?"

"Because I don't get that same satisfaction out of teaching."

"Why?"

"I don't know. Maybe because it doesn't leave anything behind."

"What about the knowledge you impart to your students?"

"Knowledge? I don't think I pass on much knowledge. I'm not exactly teaching required courses. They can get by quite well without the stuff I teach."

"Really?" Camille smiled a gently. "Then why do you teach it?"

"I see what you're doing, and don't think I'm not grateful for it," Eric said, smirking. "Okay, I teach what I'm interested in, what I'm working on."

"Why do the students take your classes?"

"I guess they think I'm moderately entertaining. I have a reputation. And some of them take them because they're offered at a convenient time."

"Come on. Your classes fill during the first hour of registration..."

"It's a big school."

"Okay. What do you think they get out of your classes?"

"They get to read some books they probably won't read in any other classes. And I make them think."

"How do you do that?"

"It's a struggle. They're not used to it."

The boy brought plates of brown meat, fried yucca, and steamed red cabbage.

"So why bother?" Camille said.

When he thought the waiter was out of earshot, Eric replied, "For Christ's sake, Camille. What are you trying to get me to say? That I am performing some kind of service to my society by teaching young minds to think clearly and critically, to see through the first, easy interpretation of things to deeper, more significant structures, making them better people, better citizens, better... I don't know what?"

"Yeah. Because you do that. And to some, maybe only a few, but I'd bet more than you know, you pass on a love of literature, of reading, studying, thinking, looking—you give them beauty, the beauty of Rilke, Donne, Shakespeare, you transform Virginia Woolf from an impenetrable, cold technician to a delicate poet of the passing moment. You enrich their lives, you know. Whether you like it or not, you are a teacher, a great teacher. I love your books as much as anybody, but it's in the classroom that your warmth comes through, that your..."

"Oh, hogwash."

"Hogwash?" she said with a sudden smile.

"Hogwash, balderdash, bah humbug, nonsense, applesauce..." Now he was smiling, too.

Walking outside after coffee, they came upon a swimming pool, faintly bluish, constructed entirely of hand-made tile. It was empty. A cracked diving board pointed like an arrow toward the drain, where a circle of butterflies opened and closed their wings in a rectangle of mossy sludge. Around it three tile-encrusted concrete recliners seemed to grow up out of the patio; they did not look comfortable.

"It's like something of Gaudi," Eric said. "There's a park in Barcelona with a kids' play area, a concrete dragon inlaid with bits of broken tile and glass. This is just like it, or what it would be like if it was moved to a jungle and left to mold."

"I've seen that park," Camille said hesitantly.

"Really? I didn't know you'd ever been in Spain."

"There are still some things you don't know about me," she said, but there was a sadness behind the smile.

"Yes. You are still quite mysterious to me," Eric said. He could see the memory of the park had taken her someplace she was reluctant to go. He could see also that she was trying not to let it bring her down.

"Places," Camille said, "and the memory of places. They have a power over us."

"Were you in Barcelona with Claude?"

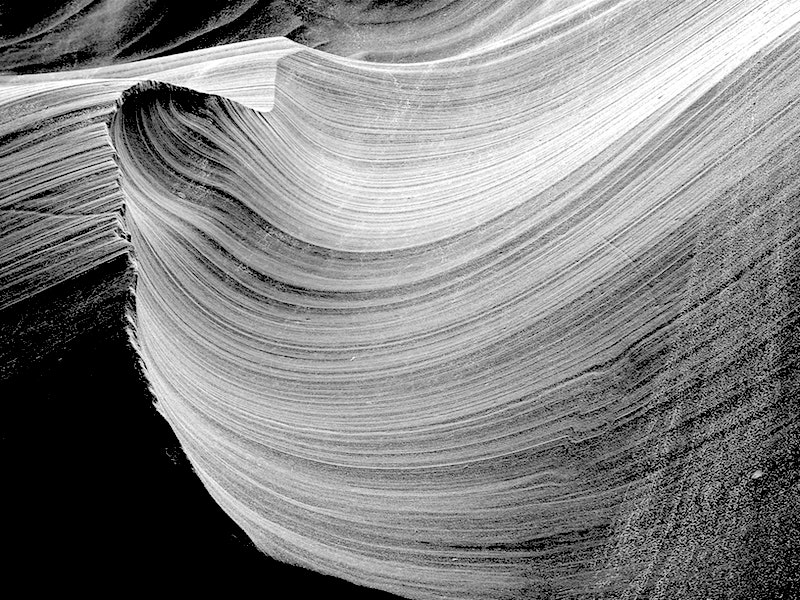

"No, not exactly. I was there alone. But I was on my way to meet him in Madrid. I got to Barcelona early, and I planned to take the evening train to save on a hotel, so I had a whole day to explore the city. I visited all the Gaudi buildings, and I bought some bread and cheese and wine and ate lunch in that park. I took several rolls of film there. But Gaudi's architecture doesn't photograph well. It doesn't have the clear geometry and orderliness of the Greeks, or Palladio, for instance, clean lines that make for beautiful photographs. It's more about texture; you have to walk around and through his work to feel it..."

Eric had sat, gingerly at first, on one of the concrete chairs. It was surprisingly comfortable after all. He was gazing up at Camille, who had stopped talking.

"What?" she said.

"Nothing," he said, smiling.

"Why are you looking at me like that?"

"I love hearing you talk about architecture. I think you're a genius, you know."

"No, you don't. You think you're a genius."

"I think I could be, if I were smarter," he said, still smiling. "But being a genius might be overrated, anyway. Especially for someone who has to work at it. Sometimes I'd rather be a fish."

"Like in the song?"

"Like in the Yeats poem: Could I but have my wish, Colder, dumber, and deafer than a fish."

"Bullshit," Camille said, grabbing his arm and pulling him up to his feet. "C'mon, let's get back and get cleaned up."

Eric felt a pang of something as they left the dark grotto with its strange designs. He still didn't know what had affected Camille, really. He knew there was more to the memory it took her back to than she had told him, and he, too, felt troubled, a faint turning in his belly, worse even than what he had felt earlier when he was writing. Sadness was seeping into him, the sadness of the tropics, he supposed, and a sense that he was adrift; like the birds Camille had described the day before, he was losing his connection with the bottom and was in danger of being carried off by hidden currents deep below the surface. Climbing up a muddy path toward the chalet, Eric's foot slipped, and he reached out to catch himself on a small tree, only to stab himself on its spiked trunk. Nature itself seemed to be against him.

"You want me to be your muse," Camille said. "Do you know how much pressure that puts on me?" She was working with the blade and tweezer of his Swiss Army knife to dig the spines out of his hand as he sat passively next to the sink in the little cottage.

"Give me a break," he said. "You know I don't believe in muses and sentimental garbage like that. Ow!"

"Sorry. This one's really deep." She started digging again. "So if you don't believe in that stuff, what is all this about me inspiring you? You say you don't believe in the muse, but you lie. It's another of your secret superstitions. I'm not saying you are lying to me so much as lying to yourself, disregarding a belief you know doesn't serve you. There is no muse but work, you say, but when you can't work... when you can't work, it becomes a problem. Don't think I'm not sympathetic, although I think you'd be able to deal with it better if you'd admit, at least to yourself, that inside you very much believe in inspiration. And I understand that. I believe in it, too. But sometimes—and I don't know why I'm telling you this—sometimes you have to work without inspiration."

She flourished the tweezer; a pointy brown woody object in its grip. "I think that's the last of it," she said, and then reached for the antiseptic and the bandaids. "Maybe it's easier for me. The world is out there—beautiful, ugly, plain, complex, whatever, it's there—and I can point my camera around and shoot. Maybe I come up with nothing worth printing, but I expose rolls of film. It feels like I'm working, even if it isn't very good work. But you have to dig into yourself and come up with words, fill up the empty pages with material that isn't outside, but inside, and sometimes it doesn't want to show itself. I do understand that, but you can't make me responsible for drawing it out. You can't blame me, however subtly, for your inability to write, or tell me that without me you'll fail completely. It isn't fair. It's too much."

"So just how much psychology did you study?" Eric asked, flexing his hand, testing it. He tried to make the comment light and amusing, but it came out acidic.

"Fuck you, too," Camille said.

"I'm sorry," Eric said. "It's just that... I don't know. A few weeks ago I was writing as I hadn't written in years. It's hard not to connect that to my feelings for you. And now... But I don't mean to make you responsible for my work. That's my problem. But things are not going well for me down here. For Christ's sake, look at me." He held up the hand she had just nursed. "I just need your support. Is that too much to ask?" He knew as soon as the last words left his mouth that he had taken a wrong turn.

"Oh, my god. Do you hear yourself? Do you have any idea how hard I'm trying to support you? But your idea of support is... I don't know... you cut yourself down, and you expect me to disagree with you, tell you you're wrong, build you back up. And then you tell me I'm wrong. Do you know how your bitterness can cut everyone around you? Do you know how it can cut me?"

Driving back to Quito the next night, they got lost in the outskirts of the city. Eric drove more and more recklessly as he became more frustrated and annoyed. They were between highways and found themselves in what seemed to be an industrial area where the streets indiscriminately changed from broad, lamplit avenues to dark narrow alleys and back again. They passed a red neon TURNO sign, indicating a pharmacy whose turn it was to remain open all night. Then, abruptly, Eric swerved to avoid a paving stone in the middle of the road, narrowly missing a deep hole the size of a garbage truck.

"Jesus Christ," he swore. "That goddamn hole could have swallowed this car, and they mark it with a fucking rock? No lights, no flares, not even a goddamned smudgepot? This is like driving in a Roadrunner cartoon, only when we go into the hole, we die." He was shaking.

"What are they going to mark it with?" Camille said. "If you hadn't been going so fast... You have to remember where you are. This is the third world, remember?"

She was supposed to lift him out of his mood, but she wasn't doing it. Maybe she had had enough, he thought. Sooner or later everyone had enough of him. Still, he pushed: "But someone could get killed if they drove into the hole."

"Like us," she said. "That's why you have to slow down. Why don't you go back to that pharmacy, and I'll ask them how we get to the center of Quito, or to the airport? We know our way from there."

The car at last pointed in the right direction, landmarks passing the rain-streaked windows in orderly succession, the cityscape reoriented around them, readable and reassuring, they had time to think. And each had the same thought: if he didn't stop behaving like this, imposing his black moods on her and expecting her to fix him, she would leave him.

In him the thought came with a bitter sense of futility, for he knew he was out of control, and he knew he would not be back in control for a while. It would hurt to lose her, but the longer they went on like this, the longer he had to see the hurt and disappointment in her eyes, the more miserable he would be. Alone, at least, the only one he would be lacerating would be himself.

In her the thought came as a way of getting back in control, a growing resolve to establish a limit and stand by it: if she refused to let him hurt her beyond a certain point—and here she admitted to herself that he was hurting her with his resentment of her work, his constant insistence on bringing her down—if she refused to let him hurt her beyond a certain point, she would not have to stop loving him.

The rain eased up as the hotel came into view. A melancholy tenderness had settled on both of them. Eric understood she would leave, and Camille understood she would leave. There would be a scene, of course, and it would be painful and sad, possibly ugly. But it wouldn't be tonight. Indeed, after they checked in with the sleepy desk clerk and carried their bags up to their old room, they were tender with one another, Camille offering herself with a generosity born out of her very determination to leave, Eric knowingly accepting her gift as a balm for his wounds, a balm he well knew would run out soon.