|

|

| Jan/Feb 2018 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Jan/Feb 2018 • Nonfiction |

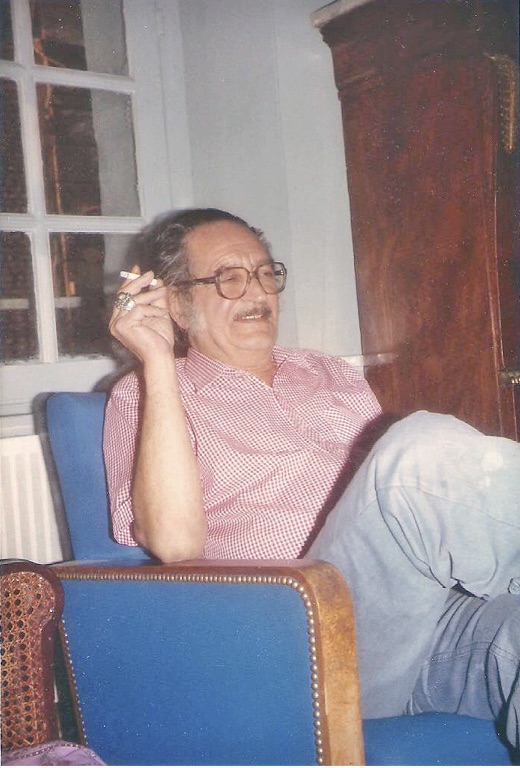

Photograph by Birgit Stephenson

The other guests in the house retired at sensible hours, but like my host I was by nature a night owl and so we talked together and drank red wine until the small hours of the morning.

The house, a narrow, three story brick building, was located at 71 rue d'Ecosse, a little side street in Dieppe, and my host was the poet and polyglot, Edouard Roditi (1910-1992). The other guests included my wife Birgit, a middle-aged French woman named Genevieve, and two young poets from London, David Miller (born in Australia) and David Menzies (born in Scotland). It was August of 1982.

Emperor of Midnight is the title of one of Roditi's collections of poetry, published in 1974 but gathering together texts both contemporary and from as far back as 1927. Although the author never attempts to explain the title, I interpret it as being psychologically self-descriptive. As an increment of the measurement of time, midnight is curious and anomalous. It is an instant apart from all others, astride two realms, uniting them, yet separate from both. It is an interdiurnum, an instant between successive days, the boundary between the last second of one day and the first second of the next day, a border and a meeting place, an interstice. The tensions and divisions implicit in midnight may be seen to be reflected in the life and writing of Edouard Roditi, who occupied a curious and anomalous position in American letters, a position apart from all others. Roditi was a surrealist and a modernist-formalist poet, a scholar, a critic (of art and literature), a philosophical anarchist and a student of mystical traditions, the author of love poems, political poems and devotional poems. He was an outsider with an Oxford classical education (Latin and Greek), a "security risk" in the U.S. and France, an admirer of both T.S. Eliot and Antonin Artaud. He was fluent in several languages other than English, including French, German, Spanish, Dutch, Turkish, Italian, Portuguese and Hebrew. In at least three of these languages, Roditi wrote poetry, while from the others he translated both poetry and literary fiction. In his personal life, too, there were complexities of identity. Roditi was an American citizen who was born in Paris and spent most of his life in France, he was of Sephardic Jewish descent, his sexual orientation was predominantly homosexual, and he suffered from epilepsy. Out of these disparate psychic provinces he shaped his own hybrid, midnight realm, a meeting place of words, styles and ideas, a sanctuary for antitheses, a personal poetic empire encompassing inspiration and control, the classical and the romantic, pessimism and despair and faith and hope.

Having spent a somewhat solitary boyhood in Paris, at the age of nine Roditi was sent by his parents to be educated in England, at Elstree School in Hertfordshire. The experience was, he said, deeply shocking. He was dismayed by the cold, unheated school and by the barbarous brutality of his classmates. It was here, however, that he had a fortuitous and memorable encounter with one of the most eminent authors of English literature, Joseph Conrad. The meeting with Conrad came about when the distinguished author was visiting the school to call on his old friend, the Head Master of Elstree. Roditi was enlisted to keep Conrad company while the Head Master tended to some pressing business. The author and the boy walked the school grounds speaking together in French since it gave Conrad (a polyglot like Roditi) pleasure to practice his fluency in that language. The matters of which they spoke were merely commonplace, Roditi said, Conrad questioning him about his studies and interests and relating in turn anecdotes from his own youth. But upon the occasion of their second and last meeting, Conrad suggested to the young Roditi that he might grow up to write in languages not his mother tongue, a strangely prescient prediction. More than six decades later, Roditi still remembered Conrad as a kindly, somewhat tired, old gentleman who spoke French with a slight accent.

Some nine years later, in 1928, at the age of 18, Roditi published his first poems in the celebrated Paris-based avant-garde magazine, transition. Writing poems both in French and in English, his method of composition was at that time that of the psychic automatism of the surrealists. During this same period, Roditi was studying at Oxford University where he wrote the first English and American surrealist manifesto, titled "The New Reality" which appeared in The Oxford Outlook. After only a few years, however, he abandoned the surrealist ethos and began writing poetry in a more formal fashion, organizing his verse in more traditional metrical and stanzaic structures. These poems appeared in mainstream modernist literary journals such as The New Criterion and Poetry.

Roditi related the story of his separation from surrealism in a document titled The Journal of an Apprentice Cabbalist: Prelude to a Vita Nuova, written in 1931 but first published in 1991. This account records how the poet's allegiance moved from Bretonian orthodox surrealism with its essentially materialist premises, toward neo-Platonism and the occult tradition, and the teachings of the Cabbala in particular. Yet, there is a sense in which Roditi may be seen not to have abandoned surrealism altogether but rather to have become two poets: one in the modernist manner and another as an independent, dissident, non-doctrinaire surrealist. The former tendency can be seen in collections such as his volume Poems 1928-1948 and Thrice Chosen (1981), while the latter tendency is manifest in collections such as New Hieroglyphic Tales (1968), Emperor of Midnight (1974) and Choose Your Own World (1992).

In 1982, at the time of our visit, Edouard Roditi was a senior figure in American letters, a living link to the expatriate writers of the between-the-wars period. His work was published by New Directions and Black Sparrow, and appeared in literary journals as dissimilar as Poetry, The Partisan Review, Kayak, and Antaeus. He had also very generously contributed poems and pieces to Pearl, a modest little literary magazine put out by Birgit and me in Denmark. We had corresponded and accepted his invitation to visit him at his house in Dieppe, travelling by train from Copenhagen to Paris and then to Dieppe, arriving in time for afternoon tea and a discussion among David Miller, David Menzies and Roditi on the merits of Finnegans Wake. "Joyce's knowledge of philology," Roditi said, "may have been sufficient to impress Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway, but would never have passed muster at a good university." I was somewhat taken aback by this disparaging pronouncement but was soon to discover that Roditi held many such dismissive opinions. In literature, there were those writers whom he admired and whose work he championed and those he thought inferior, overrated or merely wrong-headed.

At age 72, Roditi was thin-limbed with a protuberant belly. Behind large bifocal eyeglasses his eyes were hazel, sad and sensitive. His black hair (graying and thinning) was combed straight back. He wore a thin black moustache and sported long gray sideburns. He chain-smoked filtered Gauloise cigarettes and spoke with an R.P. accent (incongruous in an American citizen, of course, but he had learned to speak English originally from his English mother and at the schools he had attended in England.) He had an endearing habit (probably acquired in England) of making some humorous observation and then, as if with a start, widening his eyes, raising his eyebrows and dropping his jaw in mock astonishment and saying: "Wot? Wot? " This charming mannerism was like something out of a Wodehouse novel. One late night, for example, we were discussing the messianic megalomania of André Breton, when Roditi commented: "He must have thought he was Joan of Arc in drag." He paused for a second, then looking at me with an expression of sudden surprise he produced that face of amazement exclaiming: "Wot? Wot?" On another occasion, we were talking about the 19th century British painter, Richard Dadd, who killed his own father. Roditi observed: "Richard Dadd! Perfect surname for a parricide!" (Look of stylized incredulity.) "Wot? Wot?"

Roditi was a gracious host and an accomplished cook. Every afternoon he would shop for the evening meal, shuffling resolutely through the crowded streets of Dieppe with a basket on his arm to a market on the square of the Eglise Saint-Jacque and then to a fish market on the Quai Henri IV. He prepared delicious vegetable soups, fried potatoes, fish filets and salads, served with white wine and followed by cheese and tea, and simpler meals of scrambled eggs, ratatouille, bread and Normandy cider. Talk at the table was often literary: Djuna Barnes he admired, Mina Loy and H.D. much less so, Cid Corman and other contemporary "open form" poets he esteemed very little, Ezra Pound not at all (deploring his influence together with that of William Carlos Williams, "poor Bill" as he called him, upon younger poets), Allen Ginsberg occasionally, John Ashberry frequently, Randall Jarrell, Stephen Stepanchev, John Haines and Kenneth Rexroth absolutely, T.S. Eliot unreservedly.

Of his old friend, Paul Bowles, Roditi said: "he is a very unhappy man," withdrawn and afraid of the world, only venturing out by chauffeured car to the post office and to purchase his supply of kif. He thought that Bowles, though he pretended to a "purely phenomenological interest" in things disturbing and unpleasant, was "obsessively fascinated by what horrified him." In this regard, Roditi found his friend's attraction to the bloody and sometimes violent ceremonies of Moroccan trance cults to be "morbid and masochistic." Jane Bowles, too, Roditi remarked, had been unconsciously self-destructive. When he had first become acquainted with her in New York City in the 1940s Jane Bowles had been charmingly playful, buoyant and droll, but in her later years living in Tangier, she had become anxiety-ridden and desperately alcoholic. Beneath her puckish wit and eccentricity, Roditi believed, she had always been fearful of insanity, and in Tangier she had—much to her detriment—pursued a psychologically masochistic relationship with a malevolent Moroccan woman named Charifa, who may have poisoned her. There was a sense, Roditi said, in which Paul and Jane Bowles, both of them dear friends of his and both fine writers, were drawn together by a dark affinity. Driven by their respective obsessions, both had courted disaster in their lives.

We talked of dreams and Roditi said that during a period in which he underwent psychoanalysis he had kept a dream diary but the psychoanalyst had retained it. Imagery drawn from his dreams had been employed by him in several poems and in the collection of prose pieces titled New Hieroglyphic Tales. He was quite comfortable in speaking openly of his homosexuality, recounting with amusement how in his F.B.I. file there had been a letter describing him as a great womanizer when in fact at that time he had been "exclusively homosexual for 20 years."

Often at meals, out of respect for Genevieve, we conversed in French. Genevieve was, he told me, his "closest and dearest friend," though in truth, he said, they "hadn't much in common." She was interested neither in literature nor art, but he admired her greatly for being "unpretentious."

The hour late, the house quiet. Drinking red wine by lamplight. Roditi smoking cigarette after cigarette, wheezing, snorting and coughing. He smoked in this way, he explained, because he believed that tobacco helped to keep at bay the dreaded epileptic seizures to which he was subject. This affliction had since childhood occasioned him much distress, increasing his sense of isolation in the world. Yet often the seizures were preceded by a period of exaltation and enhanced mental capacities, during which he wrote poetry with great speed and fluency. Inevitably, however, after a time this euphoria turned to acute anxiety and physical anguish and ultimately to loss of consciousness followed by amnesia and a sense of complete depersonalization. During this latter phase, he inhabited for a time a spectral twilight state, a strange gray zone in which "one neither exists nor does not exist."

I remarked to Roditi how much I admired the elegy to Lorca he had written (part I of "Three Laments"). He thanked me and said that the poem had been deeply felt by him because he had known Lorca. They had been introduced through a mutual friend sometime in the late 1920s when Lorca was en route to New York via Paris. Roditi, a very young man at the time and still naïve concerning homosexuality, had immediately felt a deep affinity with Lorca and an intense attraction to him. They had shared a single night of love and then never met again. Some years later Roditi had with great sorrow read in a newspaper of Lorca's death. The memory of their one-night affair was even now very precious to him, the affinity between them had been strong.

Another poet, for whom he had felt a special bond of affection—though not sexual attraction—was Dylan Thomas. Roditi had first become acquainted with Thomas in London in the late 1930s and had spent many nights with him in Soho Pubs. He had last seen him just after the war and had one last pub crawl with him. Thomas's raucous, reckless behaviour was, Roditi thought, a compensation for sensitivity and self-consciousness, and for his status as a provincial Welsh outsider in the sophisticated, cosmopolitan London literary milieu. As one who as a Jew and a homosexual also felt himself an outsider, Roditi felt that there was between himself and Dylan Thomas an unspoken but mutually sensed, tacitly acknowledged kinship, a bond of respect and genuine fondness.

I mentioned having once read about his misadventures with Hart Crane. Yes, he said, what a débacle that evening had been. Roditi had quite unexpectedly one evening encountered Crane (whose poetry he revered) through a friend and had been dragooned into guiding his idol to a notorious bar in the depths of the 11th arrondissement. Crane was drunk and dishevelled, obstreperous and belligerent. Together they had travelled across Paris, negotiating dark tenement streets, and finally arrived at the bar. Almost immediately, Crane had provoked an altercation with some French sailors, and Roditi—fleeing for his own safety—had abandoned him there. For the young Roditi, not yet 20 years of age, the experience was memorably unsettling, a first-hand glimpse of a poète maudit in headlong pursuit of his own doom.

In all respects the direct opposite of Hart Crane, Roditi said, was T.S. Eliot, whom Roditi had met in London. Eliot was punctilious, polished, elegant and courteous. He was a person of absolute decorum but far from being aloof, he was genuinely gracious, genuinely kind. Eliot's careful dress and cultivated manners were, Roditi believed, a kind of protective coloration, safeguarding an essential shyness and self-consciousness in the man. Eliot had very generously encouraged Roditi in his writing, made incisive emendations to drafts of his poems, and had selected some of his poems for publication in The New Criterion. Roditi regarded Eliot as being in every sense "a saintly man" and unequivocally the foremost English-language poet of the century.

Among his contemporaries in American poetry, Roditi said, he had felt the closest personal, poetic and political rapport with the recently deceased Kenneth Rexroth. They had shared anarchist-pacifist ideals, held each other's work in high regard and found each other's company congenial. When they had last seen each other, Rexroth, already weak with ill-health, gazing at him with mournful eyes, had said: "Edouard, I wish I had been a homosexual so that we could have been lovers." Roditi had taken his hand and said: "That's alright, Kenneth, never mind. Actually, you're not my type."

We agreed that among Rexroth's best work were his translations from Chinese and Japanese poetry. Translation, Roditi said, was an art. (He had undertaken numerous literary translations from French, Spanish, Turkish, Dutch, German and other languages.) Satisfactory literary translation required many skills. You must, of course, have a very thorough grounding in the language from which you were translating, be familiar with the idioms, the weight of words, and most crucially you must be able to discern through the written words the individuality of the writer, that writer's distinctive voice. It was essential that you understand the subtleties and complexities of the text in its source language before presuming to render it in another language. You must also—and this was, he said, where so many translators were deficient—possess literary ability in your mother tongue. What you aimed to achieve in a literary translation was to create something equivalent, something analogous not only to the original text, but to the perception or emotion that had inspired the text. In translating, you were through the exercise of your own creative resources seeking to transfer thoughts and emotions from one medium to another, one mind to another, without transforming or deforming them. That, he said, was translation as it should be practiced.

I mentioned Charles Henri Ford (among my own favorite poets) to Roditi, knowing that they had both appeared in transition at a very young age. "Oh, that Charles Henri," Roditi said with exasperation, "he's so feminine! He's such a fairy! His sister Ruth even refers to him as my sister Charles Henri." Roditi went on to relate how when they lived in Paris and Tangier in the 1930s, Charles Henri Ford had had a preposterous, unfathomable affair with Djuna Barnes, even typing for her the manuscript to her novel, Nightwood. Nightwood was brilliant, of course, but Djuna Barnes was a very strange person. She had once said: "I'm not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma Wood." And now she had become a complete recluse, refusing to see anyone, never venturing out of her apartment since sometime before World War II. He had learned from a friend in New York city that a cleaning woman for the apartments where Djuna Barnes lived had carried out boxes upon boxes of empty bottles from her flat, week after week. Apparently, she'd been drunk for decades!

Roditi paused and chuckled ruefully. "What a mine of bitchy stories I am!" he said.

Roditi was exceedingly well-read in the literatures of half-a-dozen languages and inclined to promote forgotten and neglected writers. Among those whose writings in English and American literature he thought worthy of reconsideration were Edward Bellowes, Horace Walpole, James Thomson, Philip Freneau, Artemus Ward and Robert McAlmon. He valued original and eccentric writing and prized those flashes of vision sometimes to be found in the work of lesser literary lights. In Bellowes's verse he appreciated the poet's deployment of elaborate conceits and rhetorical extravagances that bordered on the hallucinatory. He thought Walpole's unremembered Hieroglyphic Tales, originally printed in an edition of only seven copies in 1785, were extraordinary and a clear precursor of surrealism. (Walpole's book served as an inspiration for Roditi's own New Hieroglyphic Tales published in 1968.) In James Thomson's The City of Dreadful Night (1880), he saw the expression of an ontological revolt as uncompromising and comprehensive as that expressed more than half-a-century later in the writings of Antonin Artaud. Philip Freneau he honoured for his Democratic revolutionary fervour, his broad human sympathies, his verbal harmonies and visionary nocturnal-gothic passages, the latter especially to be found in Freneau's long poem, "The House of Night" (1779). Roditi also commended to me the 19th century American humourists, Artemus Ward and Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby, whom he considered neglected "masters of the Absurd."

His own late near-contemporary, Robert McAlmon, he considered to have been undeservedly ignored in his time and now long out-of-print and forgotten. McAlmon's novel Village and his short-story collection Distinguished Air were very much worth seeking out. In person, Roditi said, McAlmon had frequently made himself unpopular among other writers for his waspish tongue and caustic wit. Cruel caricatures of several "Lost Generation" expatriate figures were to be found in his fiction.

An interesting link between McAlmon and Djuna Barnes, he said, was that both writers had used Dan Mahoney—a flamboyant, unsavoury, insufferable Irish-American expatriate, a transvestite queen—as a model for characters in their fiction. Mahoney was, of course, the model for Dr. Matthew O'Connor in Barnes's Nightwood, and he was also the inspiration for a short story by McAlmon. Mahoney was infamous in the Paris of the 20s and 30s, Roditi said, an abortionist, a quack, a cad, outrageously camp, endlessly garrulous, a master of malign wit, a brilliant bore.

Among living writers, Roditi very much esteemed Ned Rorem, a distinguished composer and the author of The Paris Diaries and The New York Diaries. Roditi urged me to read these books, even going to his book shelf to find his copies and press them upon me.

I thought that Roditi's championing of forgotten and neglected writers was, perhaps, unconsciously motivated by his own sense that his work had for so long been ignored and underestimated. He complained that critics and anthologists in the United States thought he was French.

During the afternoons, Roditi was engaged in writing his "confessions," as he called them. The tentative title he had given to the manuscript he was typing was "Confessions of an American Epileptic." He gave me the early chapters to read. They dealt with his childhood and the pain and shame, the distress and loneliness his epilepsy had occasioned him then. He told me that he intended to write very frankly and explicitly concerning his homosexual experiences. He thought that James Laughlin (of New Directions) would be "too priggish, too cautious" to publish the book. He also showed me his most recent poem. (I forget the title.) It consisted of two end-rhymed quatrains on the subject of the house in which we were staying. He said that 50 years ago he could never have guessed that one day he would be writing like A. E. Housman. This thought caused him to roar with laughter.

Copenhagen (where Birgit and I lived) he loved, he said, for its "unceremonious hospitality." The Tivoli Gardens he thought delightful not least for their preservation of Commedia dell'Arte performances in the Pantomime Theater there. He enjoyed Danish food (smørbrød, fresh fish) and the museums, including the Bertel Thorvaldsen Museum and the National Museum of Art. A Danish painter whose work he found compelling was Nicolai Abildgaard (1743-1809). Abildgaard combined neo-classical technique with a proto-romantic imagination to very impressive effect, he said. Particularly striking were Abildgaard's paintings illustrating Ludvig Holberg's curious satirical and surreal novel, The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground (1741). This book which Roditi had read in a French translation he pronounced to be a classic of its kind and one strangely and unjustly disregarded by readers and scholars.

I asked Roditi if there were critics whose writings he held in regard. He named Nicolas Calas and G. A. Borgese, both men skilful and original in their analyses. Kenneth Burke was remarkable, very complex, very subtle, very stimulating, if sometimes verbose. And there was also Jean Paulhan, "a very complicated man, fragile and shy, erudite." Roditi had once produced for Mesures, a literary journal edited by Jean Paulhan, translations of poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Roditi and Paulhan had had minute discussions of the Hopkins poems, scrutinizing them word by word. Paulhan had impressed him as a very serious, very meticulous critic with many insights.

What he valued in criticism, Roditi said, what much the same as what he valued in poetry: individual intelligence and taste and culture applied to shared human experiences in the world. He deplored, he said, the retreat of poetry and much academic criticism into private worlds, private myths, private languages. This was essentially elitist, he thought, and current critical and poetic preferences for what was termed "pure poetry" had unfairly denied a place to and removed from consideration many other traditional genres of poetry, including satirical poems, didactic poems, topical, philosophical and even political poems. In a similar manner, he said, he objected to the undue emphasis placed on technique in modern poetry. This was the basis for his complaint against the current generation of "open form" poets, whose poems seemed to him to have collapsed into solipsism. Technique should not be an end itself but should serve content, a content accessible to a reading public.

Perhaps because the hour was late and the darkness of the night outside was at its darkest, I mentioned that his earlier descriptions of the twilight state that followed his epileptic seizures had reminded me of lines in Eliot's "The Hollow Men," in which an attenuated existence in the afterlife is imaged as "death's dream kingdom," and as a "twilight kingdom." I asked Roditi if he thought that the state of consciousness after death would be something similar to that strange condition he had experienced. He laughed and shook his head. "I'm no prophet," he said. Then he added: "But perhaps. Perhaps so."

We said our goodbyes on the night before our departure and Birgit and I left quietly early the next morning. Host and guests were all fast asleep. We stole down the stairs and out the front door.