|

|

| Oct/Nov 2016 • Travel |

|

|

| Oct/Nov 2016 • Travel |

Rita Mae Brown once said, "You can't be truly rude until you understand good manners." Unpredictable behavior was the last thing I expected from the young German woman with whom I'd been exchanging letters.

On my flight from Kennedy International Airport to Luxembourg, I thought about Ada. She'd invited me to spend several weeks with her family in Bundenhof and would meet my train when I arrived from Luxembourg. Her photos revealed a blonde girl in an A-line dress that ended too far below the knees and had a white collar buttoned tight at the neck. Her parents appeared old and bucolic. If the World's Fair computer had matched me with a Greek or Italian woman, there might have been a chance for romance. I couldn't visualize romance with a big Teutonic woman, although I wasn't sure how tall the big-boned girl in the photos really was. What was important was her kindness with the extended invitation. I thought having a family to visit would lessen my anxiety about going it alone in Europe.

My plan was to visit Ada in Germany and travel to the Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg to pick up the new Volkswagen Beetle I'd bought through the Europe by Car organization. After one night in a small Luxembourg hotel, I was on a train to meet her.

A man in a uniform checked my passport when the train passed into Germany. I saw that some older women passengers who wore funny Robin Hood hats and carried picnic baskets had hairy legs. Weird. I went to the dining car and tried speaking German while pointing to lunch items on a menu. Even weirder. Two years of studying German at the U.S. Naval Academy was just enough to create the illusion that I'd learned something useful (which was probably true of all college life). And I never did understand why Professor Roderbourg was effeminate and liked to humiliate me in class by calling me "Kurtchen." A scrawny, effeminate German didn't fit the Teutonic stereotype. And the way he had cooed Coooor-chen like a pigeon, making my classmates laugh, made me think he had some ulterior motive in picking on "little Kurt." I'd been grateful my Annapolis classmates had seen me as a tough fighter in the boxing ring before Roderbourg performed his act. That I didn't particularly like German-Americans, including a deranged father who had abused my mother, made my visit to the Land of the Nazis ironic. I hoped Ada and her family were pleasant. If not, several weeks with them in their small town would be as claustrophobic as a child in a car when his parents are arguing.

According to Ada's instructions, I had to change trains once. After doing that, I arrived finally in Bundenhof, bumping my bags off onto the station platform. I recognized Ada and her father from the photographs. She smiled and waved as they headed in my direction. Her long strides closed the gap ahead of her father, and she said, "Welcome to Bundenhof. How was your trip?"

She stuck her arm straight out, and I shook her hand. I said, "Everything went smoothly. Your advice about trains was perfect."

Her father shook my hand, too, and then reached for my fat bag. He said, "I take it."

Ada said, "My father speaks a little English but not too much."

I smiled at her father as he hefted the fat bag. I said, "Danke schon." To Ada I said, "Tell him I speak a little German but not too much."

She told him that, and he smiled. On our way to their car, Ada asked me about my trip.

Ada was tall with a swimmer's physique. Her silky blonde hair stopped in a curled-under wave just below the ears, hiding them, making her face seem wide and her neck long.

Ada's father was a sturdy man with sleepy eyes. The heavy eyelids were like the frog's, possibly snapping shut at any moment. His thin gray-blonde hair was brushed back, revealing a high forehead. He opened the trunk of their gray Opel sedan and lifted my fat bag inside. I handed him my other bag, and he positioned that one beside the first.

Ada insisted I sit in front with her father. During the drive to their house, I twisted toward the back so I could face her as we talked. She said her older sister was visiting with a newborn baby and had lived in California with her husband for four years. She said her mother didn't speak English but not to worry. She or her sister could translate. She said, "I'm excited you're finally here. I understand you want to see lots of Europe, so I've made plans for us to travel to beautiful cities like Heidelberg and Rothenberg. I hope you like my suggestions."

In the dim light of evening, we drove past a mosaic of cultivated fields and forested hills, as if we were on the outskirts of the town. Ada's house was in a row of white rectangular dwellings with steep red-tile roofs. Ada said they lived on the first level and rented out the second level.

Everything inside was as polished as a new coin. Ada's mother was a hefty woman with a worn expression that maybe came from cleaning the house as if it were a museum.

Ada's sister Heidi was also tall and blonde, but skinnier than Ada and with a chipped front tooth that somehow made her smile more engaging. Or maybe I just admired imperfections. She sounded like an American, which I guessed she was now since living in California. She said, "Let me warn you right away. The old folks still talk about the war a lot. Just try to ignore it. One of the problems with old age is living too much in the past."

I said, "I was only three during the war, and my father didn't fight in it."

Heidi said, "My parents and aunt tend to moan about the war years and the American bombing. Like I said, if you hear them, just ignore their conversation."

I refrained from saying I'm not likely to understand their conversation. I just smiled and said, "It won't bother me."

Heidi said, "Good. I want you and Ada to have fun while you're visiting."

Heidi had come to honor her parent's anniversary, which was in three days, and to introduce them to their grandson.

I spent my first night in a cold bedroom under a warm eiderdown quilt. Apparently Germans thought everyone should sleep with the bedroom window wide open. I woke up to the smell of bacon.

At breakfast I said how cute Heidi's baby boy was but declined to hold him. I'd held Jane Lipton's infant daughter when I was 20, but only because I'd thought Jane would have sex with me if I acted paternal. As it turned out, Jane wanted to have sex regardless of whether I held the baby. So I avoided holding babies. They seemed like the slippery frogs I'd held as a kid.

Ada took me on a Sunday walk through manicured flower and vegetable gardens and along footpaths that overlooked Bundenhof and the Leine River. The walking trails that led up into the hills allowed me to see the town from above, like the cobblestone streets and the twin steeples of a Gothic church. We talked about taking the train Thursday to the Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg to pick up my new VW Beetle.

Ada said, "If this is a rude question, please forgive me. But how do you afford to buy a car and travel for a year? Heidi said not everyone in America is rich as most Germans believe."

I said, "I studied at a military college and then a state university. After that I worked as a mechanical engineer and saved as much as I could for almost three years. I was able to keep my expenses low, especially sharing an apartment with other guys. When I go back, I'll have to get another job and start saving again. I actually grew up in a poor family. I made it to the middle class by getting a university education."

I was tempted to say that one of my grandfathers had his own import/export management business in New York City and that my German grandfather had been an aeronautical engineer in New Jersey. My lazy and deranged father had drunk more beer than he sold, which was one of the reasons my family had sunk into the mud. But I was here to learn about Europeans, not talk about my sordid childhood.

Ada said, "I think my family is in the German middle class. My father has worked at Bosch for many years, and it's a big company. Now I work there, too. But I take my vacations while you are here."

"Have you ever lived away from home?"

"No, but I would like to get an apartment with a girl friend some day. My girl friend in Hannover has an apartment. We can visit her after we pick up your car. If that's okay."

"It's okay with me. I'll let you be my tour guide."

"I thought we visit her next week before we drive south to Heidelberg and Rothenberg. I also reserved a place for us on a bus tour to Paris for the first week in October. I hope you can stay until then."

I was thinking Ada and I had never discussed how long I would stay. And I had some reservations about a German bus tour. But there was something to learn in any new situation. I said, "The trip to Paris sounds great, but I'll have to leave when we return."

"Where will you go when you leave Bundenhof?"

"I'm driving to Berlin first, then Oslo, and then Frankfurt. I have a cousin in Oslo, and my sister's pen pal lives in Frankfurt."

"I'm glad you will see Paris first. It's best to see the most romantic city in the world before the others. Then you can compare every other city to Paris."

"Have you been to Paris?"

"No, but I always dreamed of going."

"Do you speak French?"

"A little bit."

"How do you say french-fried potatoes?"

"Pom freets."

I laughed and said, "At least we won't starve there."

Ada formed a mischievous grin. She said, "I know the French for wine too. It's vin. And in Paris, wine is more important than the pom freets."

Tuesday was the anniversary and a ton of food. The aunt arrived dressed in a green satin dress and matching top. Everyone dressed up for the occasion, so I put on a white shirt and tie and brown sport jacket. There were anniversary cards and flowers and bottles of booze. And group photographs in front of sliding glass doors and their big TV set. By the end of the day, my stomach felt as if strange German microbes had inhabited my intestines for a raucous Oktoberfest dance party. I'd thought eating my grandmother's wiener schnitzel and saurbraten and saurkraut and apfelkuchen had prepared me for all this. But there was no preparation for seductive dishes that were going to screw you up later.

I ate infinitesimal portions on Wednesday and walked the garden trails with Ada. I hoped exercise would drive out the German microbes. When we returned, Ada's mother and aunt were huddled at the kitchen table. They glanced suspiciously at me as I passed, and I was sure I heard the German word for bomb. Either that, or it was Heidi's power of suggestion working on a mind that had been screwed up by the malcontent stomach. Now I felt as if I was in a house that was blaming me for their terror during the war, as if I were an infant bombardier on a B-29. It was not that I lacked sympathy for innocent people getting bombs dropped on them. I just didn't like feeling that I was symbolic of that sad time in their lives.

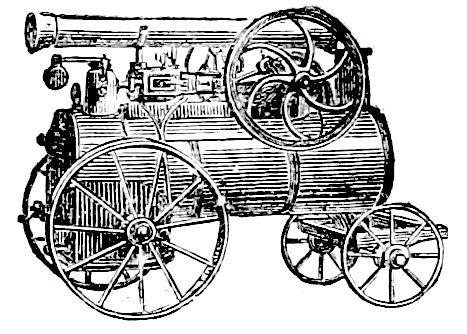

My stomach felt better the next day, when Ada and I took the train to Wolfsburg and toured the VW factory with others who had arrived to pick up cars. After the tour, I signed some papers and became the owner of a forest-green Super Beetle. Out on the autobahn I accelerated up to 75, when a Mercedes flashed past me going at least a hundred.

Now that I had wheels, I was enlisted to drive Ada, Heidi, and the aunt on a day trip to Gottingen and Goslar. Heidi said Goslar was 1,000 years old and was often called the Rome of Northern Germany. What these towns seemed to have in common was an ancient rathaus, a central square with a fountain, and medieval buildings with arches. I guessed a rathaus was similar to a New England town hall or city hall, although why town officials should work in a rat house was beyond me. Goslar had more churches and chapels than seemed normal for a town. When I asked about it, Ada said Goslar was the center of Christian worship in Germany for many centuries. We photographed one another in front of medieval buildings.

The next day Ada informed her parents that she and I were going on a one-week trip to southern Germany after we visited her girl friend in Hannover. Her parents seemed reticent, and there was some arguing that I didn't understand. Did they distrust me? Did they think it looked bad for an unmarried couple to travel together? Were they demanding that Ada sign an oath that we would sleep in separate rooms? Whatever the problem, Ada seemed emphatic with them.

Heidi laughed and said to me, "The folks are having a hard time getting used to a modern world."

The morning of our departure, I said goodbye to Heidi and thanked her for helping me adjust to German life. She'd be back in California before Ada and I returned. She gave me a hug, as if we were American compatriots.

On the drive into Hannover, it became clear Ada didn't know how to find her girl friend's street. She didn't want to ask for directions. I had to figure it out. Later she didn't know how to get to Rothenberg either. So I studied the maps I'd bought at a BP gas station.

Rothenberg is a medieval walled city on a hill overlooking the Tauber River. Ada and I climbed the town hall tower to get a panoramic view and then traversed an elevated walkway around the inside of the wall. Ada found a pension that could give us separate rooms for the night. The next day we headed for cities with famous castles—Wurzburg and Heidelberg.

At the end of the week we were in Munich at long tables, drinking beer from huge mugs and swaying to brass bands that never varied from one oomp-pah-pah to the next. I'd always thought the heralded German Oktoberfest would be more fascinating than sitting under a huge tent with people who were getting drunk on huge steins of beer. The beer had made Ada bold. She was exchanging flirtatious smiles and German dialog with a young blonde man. Instead of introducing us and speaking English, she pretended for the moment that I was not with her. Was she being rude or just immature? Maybe her parents had never taught her good manners. I felt as though my relationship with Ada should be ending but had committed to another week in Bundenhof and a bus trip to Paris.

The next week Ada and her father had colds. Ada and I walked more along the garden paths and talked. She held my hand. I wondered if it was the German friendship custom or if Ada was having romantic feelings for me. Maybe she wanted to marry an American so she could leave her old parents and move to the States near her sister.

Ada was a small-town girl with the experience of a sheltered teenager who liked American fashion magazines and pop music. But compared to the university students in Heidelberg and other young women I'd seen in our travels, Ada's clothes were ten years out of fashion—probably because of her conservative parents. Heidi had tried to modernize Ada a bit during her visit, but I didn't see their mother shortening Ada's dresses to the knees without an argument over never crossing the Maginot Line. She was intelligent with languages but had no clue how long it would take to drive from one city to another, or where to stay when we arrived, or whom to ask for directions. At first her lack of common sense in solving the trip's problems had irritated me. I'd thought she should know how to navigate her own country. But learning to navigate without her help had built my confidence for traveling alone.

Ada was immature and a bit rebellious toward her parents, even to the point of acting rudely by arguing with them in my presence. She needed to leave home and learn to live on her own. I didn't know what she wanted from me. I'd never been good at figuring out what women were thinking.

What if Ada wanted romance in Paris? My conscience said fulfilling Ada's dream of a romantic Paris trip could be a big mistake. On the other hand, Ada hadn't called me to her room during our week-long trip together. So maybe I was worried about a situation that wouldn't occur.

I felt somewhat backwards that I had reached 26 and, with the exception of Jane Lipton, Wild Woman, and the professor's daughter, I still couldn't figure out right away if a woman wanted to go to bed with me. A vacationing secretary who seemed to be encouraging me at the summer resort where I worked decided against it when I'd dropped my big hiking boot on the floor of the resort's deserted theater barn, causing the sound to echo like a thunder bolt. At Michigan State, Marcia had gone into my bedroom, then pushed me away, then came to a party two months later and said she wanted to sleep with me. I'd declined, mostly because I had trouble with the nasal sound of her voice. Another time, an MSU coed from Escanaba, Michigan, came into my bedroom and kicked the wall whenever I tried to remove her shorts, instead of just getting up and leaving the bedroom.

(Ironically, a beautiful dark woman with purple lips who was with one of my housemates in an adjoining bedroom thought this wall-kicking meant my date was having a magnificent climax and said later she wished she could have an orgasm like that. Months later I had the dark woman in my own bedroom, realized she was not responding to any kind of stimulus, and decided that having sex would only mean another disappointment for her and a feeling of failure for me.)

In Boston an airline stewardess hadn't wanted sex until she tore knee ligaments skiing with me and ended up with her leg in a cast; then she'd insisted we could make love despite the fact that a log of white cement in bed can be a lethal weapon in such circumstances.

A woman I'd loved had wanted sex as soon as I met her parents and then didn't want it anymore when I said I didn't share her dream of having a house by the ocean. And her socialite mother thought we shouldn't get serious until I got an advanced degree, saying, "Dear boy, you can't go anywhere in life without a master's degree." Since Christie had her hand underneath the breakfast table at the time, I wanted to say, "Dear madam, you can't go anywhere if a woman is holding your urgency." I thought being married with a windswept house by the ocean, screaming kids, and a mother-in-law who had excised words like penis and crap from the human vocabulary would be what a Greek philosopher had called "the full catastrophe." After Christie said she intended to date other men again (presumably those more willing to live by the ocean), I'd begun fantasizing about European women, particularly dark, Mediterranean types.

It was the second day of October when we headed toward Brussels in the German tour bus and the driver announced that a man was passing water (wasser) by the side of the road. The man was next to his car and holding his penis straight out and waving at us with his free hand. That the man was peeing in the open and middle-aged bus tourists were laughing proved Europeans were less inhibited than Americans who hid behind roadside bushes. Or else Europe had more exhibitionists.

Later the bus driver told a joke, which Ada explained to me. A Paris businessman asks his Munich business associate why he didn't bring his wife along on his trip to Paris. The Munich businessman replies, "When you come to Munich, do you bring your own beer?" I thought this tasteless joke would be offensive to the women on the bus, but none of them killed the bus driver. Either German women were too polite, or none of them were capable of driving the bus if the driver was dead.

The tour bus arrived in Brussels and emptied us into a small hotel with small rooms. Ada and I walked around the city and returned for a tour group supper in the hotel dining room. The dinner wine had Ada in a good mood, and she said she had more wine in her luggage and would bring it to my room later. When we left the table, we took our wine goblets with us.

I returned to my room, and then Ada appeared and poured from a bottle of white wine. Since there weren't any chairs in the room, we had to drink while sitting on my bed.

She said, "I know a French student in Paris. He lives in an apartment with his father. They might show us around."

I said, "It would be interesting to meet a French family."

We talked some about what the tour of Paris would include, and Ada said that, except for a bus tour out to the palace at Versailles, we'd be mostly on our own. She definitely wanted to see Montmartre, which she said was a section of the city inhabited by artists.

Even though I was often wrong about what women wanted, I didn't think she'd brought wine to help decide whether we should visit Montmartre the first or second day. She confirmed that thought when she leaned over and kissed me. We held the kiss for a moment and then put our wine on the floor. I reached over and turned off a lamp beside the bed.

I woke up at dawn to an eerie feeling that the bed was wet. I turned on the light. The bed was soaked with blood. I'd heard a virgin could bleed, but this seemed excessive. How could she not know this would happen? How inconsiderate to omit that detail beforehand? Did she want to avoid the chance that I would have declined her virginity?

As I woke Ada she seemed groggy and unconcerned. I suggested she go to her room and pack up. She did. I removed the bedding and piled it in a corner of my room, trying to hide the red part. I was sure Belgium must have laws that covered murder or virgin sex in a hotel room. The police would see the blood and question me in French. I had no idea how to say "virgin sex" in French, and I couldn't imagine Ada admitting to it.

I packed up, met Ada and the rest of the tour for the hotel's continental breakfast, and prayed that we'd be back on the bus before the maids got to my room and sounded an alarm. At the very least, ruining the sheets had to be grounds for a serious surcharge.

I held my breath until the bus pulled out of Brussels. Then I looked at Ada, who was forming a mischievous smile and holding my hand.

I hoped Ada didn't think I was going to marry her just because I was the one to take her virginity. How was I to know some European women were not experienced? It was a logical mistake.

We didn't talk about love or marriage in Paris. We just enjoyed the sights—Notre Dame, the Sorbonne, small shops on the Left Bank. Despite my unspoken reservations, Ada slept in my bed at night. The sexual adventure seemed to have Ada emerging from girl status to woman status. She spoke French with Parisians, including her student acquaintance and his father, who took us on a night tour. She seemed bolder each day.

Her new boldness provided the illusion of sophistication. Ada was still naïve really. And I was afraid of taking more risks with a small-town girl who had just discovered adventure.

The bus ride out of Paris was subdued. The noisy anticipation of our arrival in Paris had been replaced by a quiet resignation. Maybe the German tourists were returning to lives in which their jobs had no real excitement or meaning. Maybe that was a universal truth.

Ada was quiet, too. Maybe she was thinking about things we needed to discuss before I left her. I said, "I had a wonderful time in Paris. Thank you for planning it."

She said, "I wish we could have stayed longer. Three days is not enough time."

"But it was romantic. I just hope I haven't given you the wrong impression. I didn't come to Europe for romance or a permanent relationship. I came to travel for a year and think about what I should do with my life."

"I know that's the wish deep in your heart. That's a great part of your efforts. Finding your purpose first. You should never have the feeling you have any obligations to me."

I reached over and held her hand. "I'm sorry if I hurt you. I'm sorry I couldn't be what you wanted."

"I know I can accept reality, but it will be hard." Ada wiped away a tear and then another.

Two days later I said goodbye to Ada and headed for Berlin. I thought Ada had fallen in love me, or was at least infatuated to the depth of her experience. I felt guilty. It was the first time I'd allowed sex to transform a friendship that should have remained platonic. And she was the first virgin, too. They say you learn from your mistakes, though, and in thinking about it, I concluded that a virgin was likely to fantasize love with her first sexual experience, especially if she was eager to leave her parents. Ada had seemed intent about what she wanted—romance in Paris—regardless of the emotional consequences.

She'd invited me for another visit when I returned from Berlin, and so I'd said I could stay overnight before heading north to visit my cousin in Oslo. I knew staying any longer meant I would be enduring the silent stares of her parents, who now believed I was the infant B-29 bombardier who had dropped explosives on them in the war and then returned 20 years later to deflower their daughter.

I drove the autobahn to a hostile East German checkpoint that required a transit fee, paperwork, and a car search, and then traveled on to the friendly smiles at the West Berlin checkpoint. My guidebook directed me to an inexpensive student hostel near the Olympic Stadium.

I called Erika Lessner, who was supposed to be Milt Thayer's international pen pal according to the computer in the Parker Pen pavilion at the World's Fair in New York, until Milt said that the closest he'd ever get to Germany was the beer we were currently drinking in the Lowenbrau Gardens. Erika invited me to meet her at the Berlin Free University where she was a student. Erika had written that she'd like to show me Berlin. And so she did, mostly at night, because this small dynamo with shaggy brown hair attended classes during the day. She asked if I wanted to hear Billy Graham talk.

In Berlin for the upcoming World Congress on Evangelism, Graham gave a "You-need-God-in-your-life" speech in a large hall at the University. Our world is on fire, and man without God cannot control the flames. The audience seemed receptive to the American evangelist, but I sat there thinking Billy Graham's God saw more sins than the Greek Gods. I remembered praying as a child that Reverend Graham's God would fix my parents. I remembered praying He would spare President Kennedy's life after the shooting. No luck in either case. Now I was trying Greek theology, which, fortunately, included lust. I knew lust theology could lead to trouble like virgin sex. But life was trouble, only the afterlife was not—unless I met my father there someday.

Erika and I attended an American folk blues concert and then a concert by violinist Nathan Milstein at the futuristic-looking Philharmonic Hall. West Berlin was a modern city of glass and rectangular buildings like the Europa Center, which had the huge Mercedes ring on top. However, as a memorial to the war, a bombed-out church stood in the middle of this glittering city.

I wanted to see the Berlin Wall and look over the barbed wire at East Berlin. I went alone on a dreary day. I viewed the Wall of concrete blocks from a platform that allowed me to see tower guards with rifles and empty streets and drab apartment houses with bricked-in windows. It looked like an abandoned city, as if some plague had wiped out the population. I saw why some East Berliners had risked their lives trying to get over the Wall to the glittering city on this side, and why many had been shot trying it.

I whispered President Kennedy's words that I'd memorized long ago. "All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words 'Ich bin ein Berliner.'" Now I was a Berliner, too, but I didn't feel Kennedy's historic Berlin presence. Kennedy was dead, I was alone, and this was an uncivilized setting. The world had moved on without Kennedy the hero. I had to find a civilized society where his spirit still lived, where I could still feel his inspiration to do something meaningful with my life.

I returned to my room at the student hostel and read sections in A Thousand Days about Kennedy's time in Berlin. Kennedy still lived in the written word. I thought maybe books like this kept his spirit alive.

On Sunday, my last day in Berlin, I strolled through a manicured park of huge trees and endless walkways. Half of West Berlin must have been dressed up in their best clothes to walk their dogs on this sunny autumn day. If Russia had isolated them from the rest of the world with their circle of blockades, they didn't seem bothered. They seemed congenial. They had companions, if for some, just their beloved dogs. They seemed okay in their peaceful park.

Despite my time with Erika, I felt as though my week in Berlin had been empty. Maybe because I hadn't seen Erika's personal side or met any of her friends. She seemed more like a formal tour guide than the person I'd corresponded with. Or maybe I'd expected to recapture the Kennedy spirit and was disappointed about failing to do that.

I stopped in Braunschweig and spent a couple hours with Hanni and Peter Hamel, my sister Donna's friends when Peter was studying in Boston. Hanni was a stylish silver blonde, Peter was a tall intellectual. Hanni settled onto the cushions of a wicker settee, cuddling their one-month-old baby in her lap. Peter set down a tray of tea cups and a pot of tea onto a heavy round coffee table along with a plate of sliced stollen—tasty sweet bread packed with raisins, currants, and cherries. Even though Hanni had dark circles around her eyes, she was cheerful and wanted to know what Donna was doing these days. We talked about my sister and Boston. They cheered me up a bit. They invited me to return for a weekend. They seemed genuine and not inclined to ask me to hold the baby, so I said I'd come back.

When I arrived in Bundenhof, Ada retrieved the new car radio she'd ordered for me with her 40 percent employee's discount. She had insisted my car needed a radio, and it would only cost me 45 dollars. I installed the antenna and hooked it to the radio. The Blaupunkt had AM, FM, and short wave. Ada and I tested it in the driveway and picked up modern music stations across Europe. She said, "You will be happy you have music."

She asked me to return for a longer visit at Christmas, but I said I hoped to be in Switzerland by December. I couldn't say I resented her decision to have me take her virginity without consulting me first. It was a form of rudeness defined by hiding important information. But her sad expression hit my guilt chamber again, and I said I was sorry about Christmas even though I wasn't. I said I could stop by for a night when I returned from Norway. When we embraced beside my car the next morning, she said, "Just send me a little postcard sometimes."

Driving north, I sensed Ada and I had different anxieties. I was afraid of the uncertain road ahead but excited about it, too. I thought Ada, now that she'd had an adventure, was afraid she was stuck in an insular life that inhibited her dreams.

(Some names have been changed out of privacy considerations.)