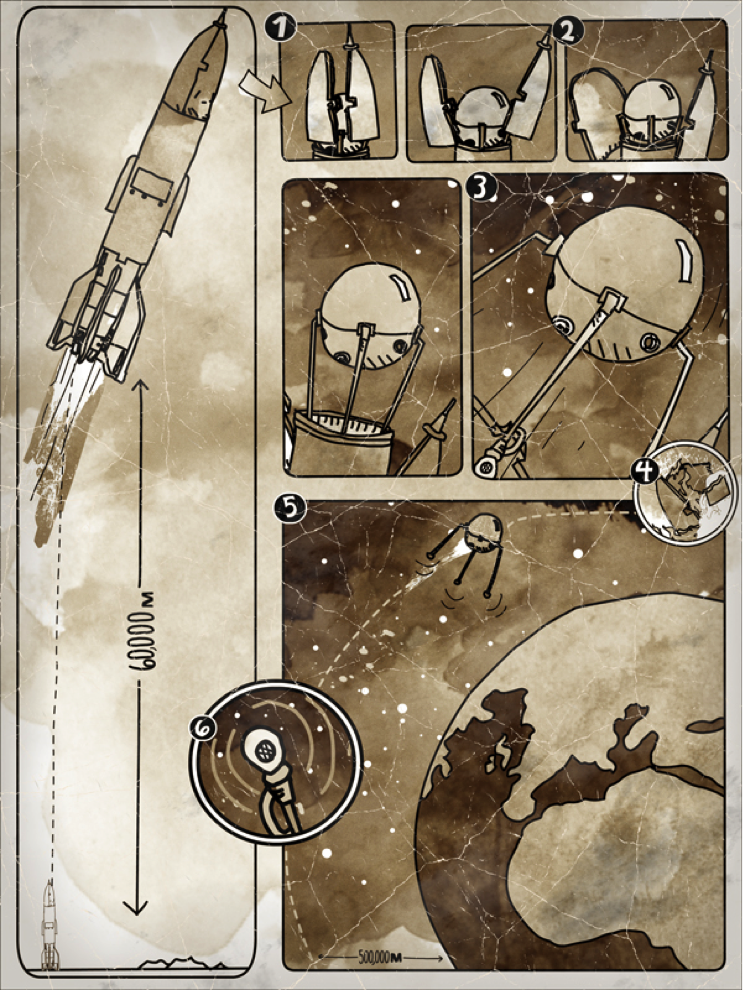

"Little Moon," First Interplanetary Radio Station, 1937 Notebook, Ivan Semilliovich Korolev, Moscow, USSR

"The bear... will never give up his forest to anyone." —Vladimir Putin, Annual Press Conference, Dec 2014, Moscow, Russia

US-RUSSIA TENSIONS ON SPACE STATION CONCERN LAWMAKERS

Wednesday, Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Fla., raised concerns on the Senate floor about potential fallout if Russia bans export of its RD-180 engines to the USA. The engines power the Atlas V rockets used for heavy launches. "This is a very complex issue," Nelson said. "It affects not only our military access to space, it affects our civilian access to space." —USA Today, May 16, 2014

Moscow, 1937

At 9:30 on Thursday night, Ivan Semilliovich Korolev returned home from his office at the National Science Institute No. 3. He climbed three flights of stairs to his apartment and found himself out of breath. Standing in the doorway, wheezing, feeling the tightness in his chest, he contemplated the events of the past week.

He was no further along with the engine problem then when he had begun working on it Monday. Indeed, this problem presenting itself as a minor obstacle at first had mushroomed over the course of the week into a major crisis. It was now no longer simply a matter of an erroneous calculation; there was the growing and ever daunting problem of materials. He had attempted to alert his colleagues with a request for new materials on Tuesday. He was informed on Thursday it would be in his best interest to wait patiently until he heard back from the Central Committee and to withhold any further demands.

The fact the Central Committee, and not merely the Institute's Scientific and Technical Council, was interested in his activities was not at all heartening. He had long held a deep and abiding suspicion his position in the research department was being undermined. He did not care to consider who exactly was behind the most recent development, but he could guess. The Second Five Year Plan had become an experiment even Pavlov could not have dreamed of. It had produced a new type of scientist: a petty bureaucrat, whose findings always miraculously corresponded to State demands.

He thought of Glushko. Would Glushko be named the next Deputy Director now that Klemmenov had been deposed? Or perhaps Frenkel? They were all mere opportunists, apparatchiks of unsightly character. Korolev would not cast his lot with any of them. He would find a way to continue his work without their cooperation, to hell with the recent Institute reorganization. If you lie down with the dogs, you will get up with fleas.

Korolev felt a profound sense of fatigue. Instinctually, he reached for the bottle of vodka hidden behind the bookcase and filled the small glass on the table. Then he sat down and drank the entire glass in two gulps. The taste of the liquid in his mouth brought a warm rush to his head. He felt a sudden if only momentary sense of relief, almost happiness.

He realized he was still wearing his coat. He would take it off once he warmed up. It was late April, but even still there was a relentless chill in the air.

The week before, Xenia, his wife, had complained about the draft. She had charged him with a lack of concern for all earthly matters. Well, it wasn't so easy. There was always the problem of materials. It didn't matter that he had the position at the Institute; he still couldn't take things without having to account for them. Now that they had their own apartment and no longer lived with his mother, Xenia had no right to complain.

He knew Xenia would be coming home soon. She had recently been selected from a handful of his comrades' wives to serve on the Executive Organizational Subgroup of the local Committee of the Women's Movement. Her recent activism troubled him. She had come home after one of the meetings dabbing her eyes with a handkerchief and blowing her nose. A member of the Central Committee had died the day before, Khojayev or perhaps Sloskovich. She had never known him nor expressed an interest in the man's career, but somehow the discussion at the meeting had moved her to tears.

It seemed to Korolev that Xenia was more disturbed by the Central Committee Member's death than she had been by the death of her own father two years earlier. Korolev did not know why he found Xenia's expression of public grief so troubling. After all, he had been the one to encourage her to join the group when she expressed reluctance.

Xenia was giving a speech tonight about her work with the Young Pioneers' theater at a women's dormitory near Red Square. Xenia would come home with news of the meeting, her cheeks flushed from the effort, her grey eyes tired but bright. She would sit down beside him still wearing her coat, shivering, her legs slowly sliding out from under her, all white from the cold. She would fumble then with the pins in her hair, trying to pull back the black strands falling over her face.

As she did this, Korolev would pour her a glass of hot water for tea from the samovar, which it was his duty to light when he came home each night. Then they would proceed to have their evening meal, a piece of the cabbage pie Xenia baked every Tuesday and proudly decorated with crusted flowers and birdlike shapes.

How many times had the two of them reenacted this evening ritual? Yesterday, Korolev had forgotten to light the samovar, and Xenia had registered the act with an icy stare. It was as if his negligence had been intentional and marked a growing distance between them. There was nothing Korolev could do to make amends for the small act of forgetting, and Korolev could still see Xenia sitting there before him, full of sadness and rage. Her expression made him look at her differently. It made him measure the growing weight under her chin, the way her black hair had grown thinner and blood vessels and age marks had attacked the once smooth skin of her face.

"What are you doing?" Xenia had snapped, and Korolev had not answered. But she knew what he was doing, and it did not please her. Avoiding further friction, Korolev had gotten up then and poured two cups of tepid water from the samovar. He could have reached out, placed a finger on Xenia's pursed lips, rubbed her shoulder, made some sort of conciliatory gesture... But he had not.

They had eaten slowly, Xenia sipping tea, Korolev vodka. They had talked in the steady, mechanical rhythm of two women kneading bread.

"I'm worried." Xenia had said, her voice a hoarse whisper, her eyes fixed upon her plate.

"What about?" Korolev asked hesitantly.

"I am worried about you."

Reluctantly, Korolev nodded. It was as if he was the last man in Moscow to be informed of a problem clearly everyone else knew about.

"We need to have a baby." She continued. It was less a request then an order. Her tone was dry and matter of fact. She used the same tone when she complained about running out of cooking supplies.

Korolev got up. The room lurched forward before him, Xenia's voice pounded on his skull. Then Xenia's face was very close to him: hard eyes and brutal lips. He smelled her, too, smelled the orphanage where she spent her days. They began making love in a haze.

But even still, the soreness had remained with him, long after the trying and fumbling. All day he felt it, felt the sting when he tried to urinate. It was his true and lasting memory of that which had passed between them last night.

Were they destined to repeat the cycle? Today, Xenia would return home with more stories about the Young Pioneers. He knew the stories about these little children, foot soldiers in the coming revolution. He did not want to hear them once more; he did not want to hear about the Women's Movement or any other movement. He had had his fill of the Revolution for the day. He wanted to be left alone, to forget about the Central Committee, the subgroups and directors, the apparatchiks with their empty slogans, and the assembly he had sat through only a few hours earlier. What use was it tormenting himself over what had been said and by whom? Aren't all cats black in the dark?

Korolev opened the notebook before him, his thoughts drifting to RP-318, the rocket that now sat in the Institute's hangar. The test was scheduled sometime next week. But it seemed impossible to meet this deadline without risking another accident. During the first test, the fuel in the ignition had caught on fire and ignited the entire stand. The accident had cost Korolev dearly. The original rocket had to be rebuilt from the damaged materials, and a comrade had been severely burned.

Korolev stopped and pulled out his mathematical rulebook, but somehow he was distracted by the sounds of the building's other inhabitants. He listened to footsteps above him growing more distant and then heard the washbasin flush.

Another thought followed, just a conjecture. The fire was not caused by human error; an enemy had tampered with the engine!

Losing focus, Korolov underlined the X he had just written on the page. The battle lay there before him. Everything else was a distraction. He found himself staring across the room to the bookshelf. He tried to read the titles printed on the book spines: Jules Verne, Bogdanov, H.G Wells, Kibalchich, Tsiolkovsky.

Recently, Korolev had begun writing fiction. He had written fiction as a student, but that had occurred under the watchful guise of his instructors and the Party leadership. He had even won a student prize for one of his stories from the Union of Soviet Writers. But those stories had been mere imitations, poor copies of great works. Korolev had been unable or unwilling to cut from the cloth of invention.

Now, Korolev was writing just to write, writing for no one but himself. Of course, everyone knew keeping a diary was inadvisable, but writing fiction? It was part of engineering: a way to define new challenges, think about problems, find new solutions. If the censors didn't approve, to hell with them! Sometimes it was easier building a radio station on Mars than dealing with the authorities.

A memory flashed, an image Korolev had seen in Pravda. There was Stalin standing by the Belomorkanal.1

Another figure flickered, perhaps a Central Committee member—Yezhov, Molotov?2

The face burned brightly for a second then began to fade.3

An ethereal light filled the room, and with the light came a profound sense of weight. Korolev felt it like a tug at his side. He, who had dreamed of weightlessness, of defying gravity, was being pulled back to earth.

Korolev remembered an incensed discussion with Glushko. They had been in violent disagreement about the purpose of new missile launches along Russia's western borders.4 Korolev shook his head; he had nothing to gain by worrying about the matter. It was beyond his control, a simple diversion from his broader goals.

Taking his pen in hand, Korolev began to write.

I do not know how long I lay there, but when I came through, I knew something had gone wrong. I sat up and felt a sharp pain in my side. The air around me was black and full of dust. I strained to make out faces, shapes, familiar landmarks, anything in the haze.

The pen leaked ink on the page. Korolev stared at the inkblot, tracing out the shape of its formation, the angle of light on its surface, the concealing darkness of its viscous depth. He continued writing.

I saw burned metal, steam, ash, wood, red cloth, dust. I heard screams. Men crying, then a garbled radio transmission from the cosmos above. A cryptic message followed. The war was coming, the war was vast and never-ending, invisible. You could not see it...

No that wasn't it. He needed something else, something more... Crossing out the last line, he continued in small, even spaced script to conserve as much paper as possible.

I saw a man's hand in the rubble. It looked to be clutching the handle of a crate. Then it came back to me. I was still near the launch pad. We had been loading petroleum canisters into the craft. There had been a sudden and intense heat. I-46 had stood beside me. Now, I was staring at I-46's hand. It had broken free from my friend's body...

The wind shifted, rattling the window open. Korolev felt the draft Xenia always complained about, saw the two sides of the window flapping like the wings of a caged bird in flight.

Old habits die hard. If he kept drinking, he would have to get another bottle. Another bottle was always a great expense. Xenia would not be happy.

He brought the small glass to his mouth and drank slowly, waiting to feel the warmth, waiting to taste the burn. But he felt nothing, tasted nothing. He set the glass down and inspected the bottle. Perhaps it had been diluted? Some black marketeer was always trying to make a small fortune by adding water.

There was only about one more glass left. No use saving it. Xenia wouldn't miss it. He filled his cup and drank. But this time, when he set the glass down, he was surprised to notice some liquid still in the bottle. He raised the bottle up before him and stared at it.

In the light, he could make out the dirty stains of his fingerprints on the glass. He could see too, a yellowish filament around the bottle's edge. He pressed his finger directly over an older fingerprint. Then, turned the bottle upside down above his glass and watched the last of the liquid pour out.

He looked down at the page. He had retraced the X so many times, pressing down so hard, that the page had torn through. He screwed his eyes up and saw a haze of numbers and letters giving way to the radio across the room.

Getting up, he walked over and turned on Radio Moscow. The announcer's voice came out in fits and starts.

School children make preparations for our great May Day Celebration...

In Paris, the Soviet exhibition opens to record number of visitors...

Then music... the nightly concert program began.

It was later then he had expected. He closed his eyes, listening. The pianist was making her way through Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major. She was playing the second movement, the slowest.

How many times as a child had he listened to his mother practicing this concerto? He would lay there on the Persian carpet, staring at her back, reading a book about the colonization of Mars. His mother kept playing, her body rising and falling above the piano like a wave. He could see the cover of the old book and the small birchwood toy plane on the floor beside him.

Static.

Korolev opened his eyes, got up from the table, and struggled for a moment to keep his balance. He made his way cautiously to the radio, focusing on the path before him. He had to admit he felt lighter than he expected to. Reaching the radio, he fiddled with the dial. The music came back, sharp and concise. He took his seat by the table once more and drank the last of the vodka. Eyes closed, his past melding with his present, his mother's figure seated by the old piano giving way to pure sound.

He followed the player's wide sweeps. There was an intense and moving beauty to the music. It opened a door right there before him. He walked through.

His mother had taken him once to a recital in Kiev. He had worn his best Sunday suit, and everyone who saw him had called him a "little angel."

When the pianist stopped playing, he opened his eyes. The door to the apartment stood open. Xenia was standing at the threshold, frozen like some statue. Behind her stood male figures; their faces in shadows. For a minute, he thought he was imagining things. He tried to count the number of men.

Two. No, three.

As he did, they began moving towards him.

He could hear the rise and fall of the broadcaster's voice. The pianist herself, thanking him for the opportunity...

Static.

A news broadcaster, "An expedition team lead by comrade Otto Schmidt has reached the North Pole in the high latitudes of Server-1..."

Xenia was still standing at the open door, her body frozen, her mouth moving, slowly, quivering, but producing no sound. Korolev screwed his eyes up to get a better sense of her expression. Her features were drained of all color as if she was staring at a ghost.

Moscow, 1957

The old man who had been allocated a room in the apartment at 25 Norenskya seemed oddly out of place in the youthful atmosphere of the building. Most of the tenants were film students at the All-Union State Institute of Cinematograph, and many of them were living there illegally without official residence permits. But in 1957, housing shortages being what they were, a newly married couple could expect to wait five years to get an apartment, and most students faired no better off. People did what they had to, to find a place to live even if it meant breaking the law.

One day in early October, Sergei, a second-year film student who lived in the building, found himself staring down at the old man lying prostrate before the stairs on the third floor. Reaching over, taking the old man's hand in his, Sergei felt for a pulse. His heart was still beating, but it was clear the old man had suffered some sort of accident. His face was pallid, his eyes clouded over. When he tried to speak, the effort caused him to hack and wheeze.

Seeing nothing else to do, Sergei called a doctor. An hour later, the doctor arrived and took the old man, despite his protests, to the hospital.

After two weeks, the old man had still not returned. When Sergei met his friend André, a first-year student, he told him a room was vacant in his building.

"And the old man who lives there?" asked André.

"Dead or in a coma, and no one has informed the Housing Authority."

André moved in that evening.

The room itself was not large. The walls were yellow and stained, the air damp and the ceiling covered with a network of tiny cracks spreading across it like the veins of a leaf. André did his best to clean up, dusting the windowsill and washing down the floors.

As for the old man's possessions, they were not many: pants, a shirt, a sheep skin coat, a small black box, a notebook.

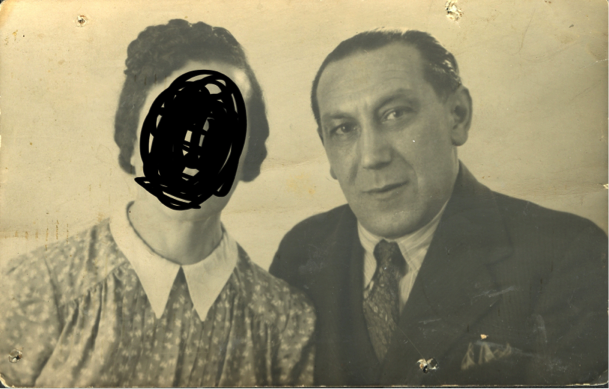

André tried to open the box, but it was locked. He shook it and heard some sort of metallic object clanging inside. He then took the notebook in his hand, thumbed through it. The pages were filled with neat, perfectly spaced handwriting. There were calculations and sketches, diagrams of rockets. One diagram struck André: a radio station orbiting the earth. In between two other pages, André found a yellowed and aged photograph of a couple. The woman blacked out, the man half-smiling, eyes sharp.

Unable to bring himself to throw out the old man's possessions, André tucked them away underneath the bed.

Three weeks later, Sergei, André, and Sergei's girlfriend, Lena, were playing cards in the kitchen when the postwoman arrived. It was Saturday, and the radio was turned on to the folk music program.

There were the usual papers, Moscow Pravda, Soviet Russia, and Lenin's Path, and also a letter addressed to: I.S. Korolev.

André explained, "There is no one here by this name."

At this point, Sergei interrupted, "How can you say that? You are living in his room!"

Upon hearing this, the postwoman stared at André, shaking her head in an expression of fatigue and disdain. She set the letter down with the rest of the mail and continued on her route.

After a little discussion, the threesome decided to open the envelope, and Sergei, in his most eloquent actor's voice, read the typewritten letter aloud.

In view of circumstances that have recently come to light, in accordance with the ruling made on April 1957 by the Military Board of the Supreme Court of the USSR, your wife, Xenia Korolev, who died in confinement on January 11, 1938, has been posthumously rehabilitated. The sentence she was to present against (you) Sergie Korolev before the Military Board of the Supreme Court on January 10, 1938 was never completed due to complications with her pregnancy. The case against (you) Sergie Korolev is, therefore, closed due to inconclusive evidence.

André looked at the letter, holding it up to the light, feeling the weight of its message in his hands.

"What should we do with the letter now?" he asked.

Lena responded, "Well, it really shouldn't concern..." but then she stopped mid-sentence, half frightened by the sound of her own voice. She heard her parent's generation.

André, set the letter down on the table and brought the envelope towards him, running his thumb along the edge of the stamp. Before him a Soviet gymnast struck a tight pose as he twisted and turned, summersaulting through the air. The caption read "The 16th Summer Olympic Games, Melbourne." André had followed the games religiously that past summer, dreaming of one day traveling to Australia and other places outside the Communist Block.

The stamp was a collector's item. Of course, André would not admit to Lena or Sergei that he still collected stamps, but hobbies born in childhood are the hardest to give up.

The radio played a balalaika tune accompanied by an accordion. Everyone listened for a brief moment, as if they were contemplating the score to one of their film projects.

Finally, Lena said, "I suppose it would be our duty to turn it over to the House Management Committee. There really isn't anything else we can do."

André shook his head. But her logic was clear. Yes, there wasn't much they could do. The man had been fully registered at the address.

"You're right," he said grudgingly.

But then the thought occurred to him it was Saturday. Clearing his throat, "There is no use trying to get there now. They won't be there."

Lena, smiled in tacit agreement. It was almost as if they were acting out lines they had already rehearsed.

"What's the great hurry?" André sighed. Informing the Housing Committee wouldn't do a thing to help the old man. The Committee would simply file the letter and reassign his room to some new person.

Sergei distracted, spoke out, "Listen guys, " he said, "I can take it. I can hand it in when I go to see about the broken faucet."

Sergei had volunteered to register a complaint about the broken faucet two weeks earlier with the Housing Management Committee. He had joked the broken faucet would be an excellent topic for his second year film project. He could shoot it like a documentary, following the story as it developed, with no prior plan. He could even present the final film as propaganda and create a series of mock news reports.

Everyone had agreed. It would be a refreshing change of approach: a film without a script. It would certainly pass the censors, since they would have no script with which to find fault. But in the intervening weeks, Sergei had forgotten about his project or decided it was not worth his while to lodge the complaint.

Sergei continued, "Why are we all sitting here? It's Saturday. Whose deal is it?"

"Who's deal do you think it is?" André responded, his face lighting up, sensing that Sergei, in his own quiet way, had put the whole issue of the letter to rest.

But just then the nightly news began. The broadcaster's voice came over the wire loud and triumphant.

As result of great, intense work of scientific institutes and design bureaus, the first artificial Earth satellite has been built.

From Paris to Berlin, from New York to Tokyo, everyone was talking about the strange transmissions emitted from the little soccer ball of a satellite the Soviets had launched into orbit. No one could believe it.

The three students remained silent, breathing in the reports.

In spite of the news, André could not stop thinking about the old man. André remembered the old man's notebook, the plan for the radio station, the cryptic passage about war. André remembered the antique photograph. A door opened before him.

André strained to make out outlines: a man seated by a table, a woman standing in a hallway, stars. André closed his eyes. He felt himself getting lighter, floating out above a wide, vast expanse of uncharitable territory. He was giddy and seasick, flipping and turning, a gymnast in air.

"Strange." André said, out loud. He was back in the kitchen.

"Yes." Lena and Sergei agreed, shaking their heads. It was strange. Very, very strange. But no one was certain if they were talking about the news report or the letter addressed to the old man.

Then, since there was really nothing else they could do, nothing else they imagined they wanted to do, they went back to their card game. They had not yet resolved the question of who would deal the next round.

1 The Belomorkanal (White Sea Canal ) was often presented as the success of the First Five Year Plan. Its construction was in 20 months, between 1931 and 1933, almost entirely by manual labor.

2 Stalin with Nikolai Yezhov (head NKVD, the secret police), Voroshilov, and Molotov, inspecting the Belomorkanal (April 22, 1937) http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/revelation-erasure

3 Stalin with Voroshilov, and Molotov, inspecting the Belomorkanal after Nikolai Yezhov was removed from the original image and replaced with a stretch of water. (1940, http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/revelation-erasure)

4 The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact defining the “Soviet Sphere of Influence” would be signed a year later.