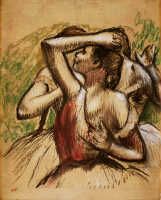

Crimson by Degas

"Exactly why would an artist go out with an accountant?" Mercer said.

Instead of answering, his secretary Beth-Anne wrote down Evelyn's number on a post-it note and reached it over. "You want it or don't you?"

"Why doesn't she have anybody?"

"Why don't you?" she said.

"You know why I don't have anybody, I'm a louse."

"You're not a louse, Mercer, but you do have your faults. So does Evelyn."

"Faults? I don't have any god damn faults. I don't have a god damn temper, either."

"Funny, Mercer. I meant your sense of humor."

"So what's Evelyn's faults?"

"Well I don't know all of them. She only came to the painting class about half the time. I was surprised to run into her at the store in fact, because one thing is she's afraid to go out anywhere, you know, in crowds and that. That's why she stopped coming."

"She's agoraphobic?"

"Damn it, Mercer, yes. She can't stand the sight of the Agora."

So now they were sitting across from each other in the restaurant, Mercer and Evelyn, waiting for their food. He didn't really like Greek food, but he couldn't resist bringing her into the Agora. Not that she had gotten the joke. He smiled, first thing, but she had a pale white face that was a little pinched, what with her sharp little nose, and she didn't smile back. Her hair was straight and black, which he liked okay. But before their water came, she had started listing her many faults, as if that was perfectly normal. For example, depression.

"So why don't they give you medicine?" he said.

"Doesn't work."

"Well how do you know it doesn't work if you don't try it?" He tried another smile, but Evelyn cleared her napkin and silverware out of the way, as if it took a certain amount of space to say what she had to say.

"I'm on Lithium and Pamelor now, okay? They don't do anything. It's nothing but malpractice insurance for shrinks."

"There's got to be something they can do."

"Oh there's lots they can do, and they've done it. Even shock therapy. It's still the same."

"This shock therapy," he said. "Isn't that risky? Doesn't it burn out your circuits?"

"It only goes one way now. When the current went both ways, that's when you got some damage."

"So it doesn't work," he said.

"In my opinion it doesn't."

"And that's all they can do? Isn't there an operation or something?"

"You mean take out the part of my brain that's bothering me?" she said. "Like the whole thing?" He was obviously touching some nerves. But maybe she'd been waiting for somebody to touch those nerves. She said, "I'd have a lobotomy if I thought it would help."

"I didn't mean that. Just a little tinkering here or there," he said, miming a screw driver.

"Right, because that's about what they'd be doing, isn't it? Tinkering? They don't know shit about how to fix people, do they? I even tried MAO inhibitors. I wouldn't have stayed on those even if they did work. Couldn't eat bananas or chocolate or cheese. Do you know how many foods there are with cheese? I couldn't drink coffee or red wine. My life is nothing if I can't drink coffee. I didn't mean to monopolize the conversation." She squeezed one hand with the other, to calm herself.

"I don't know what to say," he said. "My favorite cheese is Gorgonzola."

"Tell me about yourself. I never went out with a man who limped before. You look swashbuckling, like a pirate."

"A pirate?" he said. "It's not exactly a peg leg." He watched her eyes as she spoke, trying to get a handle, but the only change he could see was that she talked more and more. There didn't seem to be a pattern to what she was saying either, but that didn't bother him, he was game for anything. But there was no twinkle in her eyes. If he didn't find a twinkle, he knew he wasn't getting anywhere. Yet she did seem excited.

"It isn't a peg leg," she said. "But it does have a history, doesn't it? Unless it's a birth defect. But even a birth defect would be something. Tell me it's none of my business. Tell me you mind me asking. I'd like to know is all. Did you do something heroic to get that limp? Were you in a war?"

"No," he said, "I was never in any war."

"Not Vietnam?"

"During Vietnam I had to take care of my sisters. You know, hardship, no father."

"That's important," she said, tossing her dark hair out of her eyes. Her face seemed a little less pinched. "I'll bet you would have gone if it weren't for that."

"No, because of the leg."

"So you had it then? Well if it wasn't a war, were you in an airplane crash? Did you save someone on a subway track? I have nightmares about that, about being pushed in front of a train, and then someone strong always comes along to pull me up."

He wasn't quite sure how to take her. "It wasn't anything like that. It was my neighbor's .22."

"So it was a shootout! Were you feuding over the property line?"

He watched her closely, sensing a grin but not finding any. "He was going to shoot someone is all."

"You stepped in front of a madman with a gun? Whose life did you save, anyway? Your own? Some lucky lady's?"

"He wouldn't have killed her."

"So it was a lucky lady. How brave."

"It was no big thing. He'd shot her in the foot once before to keep her from running around. Didn't stop her then either. He wasn't trying to kill her."

"You didn't know that. You tried to stop him."

"I got in the way," he said. "I'm no hero."

Their dinners arrived, and she looked at him closely as he cut into his lamb, like she was measuring him. He didn't know what to say. She completely ignored her grape leaves. It made him feel funny, like this wasn't a normal date, but something might actually come of it, though what he didn't know. She frowned and said, "I'll never chase you. I won't chase anyone."

His mouth hung open for a moment, until he realized a piece of meat was about to fall out. He said, "Honest Injun, I'm a little old-fashioned. If it comes to that, I'll chase you." But he was thinking, where did that come from?

She looked at him, nodding her head like a school teacher who knows exactly what you've done wrong, and said, "You think you can rescue women."

"Wait a minute, I never claimed any of that."

"No," she said, "I'm talking about what you want. To rescue someone."

He felt nervous. "I do a lot of that at tax time, I admit it. Why don't you tell me about your painting. Are you any good?" It was a stupid dodge, he thought, but she went for it, and she launched into a whole whirlwind tour of what was wrong with art, hers and everyone else's.

When the meal was over, he had no idea what to do next. She had been strange the whole time, and he didn't feel quite right about asking her to his place. He decided to test her instead, by showing her his office. If she got too bored and wanted to go home, then probably it wasn't meant to be. But if she seemed interested in tax law or the hopeless state of his accounts, then he figured maybe something would happen.

The office was in an old building under repair. In fact it was a torn up mess that smelled of mildew and ancient wood. "Most of my clients pay late," he said as he took her up the rotting staircase. "We're renovating," he said, but everything was stripped down to its bare essence, and there was no sign of reconstruction.

She didn't say much, so he told her a few of his stories, the dirty little secrets about his clients. Which ones were cheating the government, which ones were cheating their business partners, or even their spouses. Which ones were so far into the red, the only sensible way out was something crazy like suicide.

"Why is that crazy?" she said, her arms folded as she surveyed the room.

"Because most of the time it's fatal."

"So why don't they declare bankruptcy?" she said.

"Because usually there's a wife involved. They don't go in for bankruptcy. If you're married, you've got to kill yourself plain and simple."

"You think women are mercenary?" she said.

"Not all, just wives. Remember, I've have some experience."

He went on to tell her about all the scams his clients were running, from computer piracy all the way down to restaurateurs fighting each other at auctions, all to get their hands on old meat, refrozen dinner rolls, or lettuce with bugs in it. Evelyn listened to all this, and even seemed interested. His test had come out okay then. He thought about trying to kiss her, but it didn't feel right. Instead, he suggested they go back to his place. Just like he feared, she said no, she wanted to go to her car. She didn't seem upset, only sure of herself.

"Whatever the lady wants," he said, a little defeated.

On the way back to the restaurant, they drove along the quiet streets and he couldn't think of anything to say. He felt like he had been cheated, like he had missed a signal somewhere. He did figure, out loud as he pulled to a stop beside her car, that he had earned an answer to at least one question.

"What's that?" she said, opening her door before he could even unbuckle himself. He got out and followed her to her car.

"Whether or not you had a good time."

"Couldn't you tell?"

"No. I guess you didn't. Sorry. I tried."

She slid into her car without looking at him, and said in a quiet voice, "I had a nice time."

He was surprised. "Then can I call you tomorrow?" He had his hand on the open door, but she didn't say anything. "Are you going to talk to me?" She only stared at the windshield. "Did I do something wrong? You could say something."

Finally, he got frustrated and shut the door. When she was gone, he could have kicked himself. Him and his temper. He should have been patient and waited as long as it took to pry an answer out of her. What was the matter with her, anyway?

He waited an hour and then called her. No answer. She didn't even have an answering machine on. So he had ruined it after all. How could she be that mad at him? And what was all that crap about wanting to rescue someone? He didn't want to rescue her, he wanted to go out with her. She didn't need rescuing, she needed to smile. What he needed was a joke he could tell, or a surprise that would make her laugh. Trouble was, with someone like her, there was no such thing. You could stand on your head and turn cartwheels and she'd keep right on frowning.

"Burlington Brothers still hasn't paid," Beth-Anne said when he got into the office the next day.

"So send them a letter."

"Mercer, I've sent letters. At some point you have to cut people off and start the collection process. It might help if you took one or two of them to court."

"They're my clients. They're our bread and butter."

"They're barely birdseed, Mercer. It's pretty hard to pay bills this way."

"I gotcha," he said, knowing he could never do any of that hard-nosed stuff.

"So how was your date with Evelyn?" she said.

"I don't know. She won't answer her phone."

"Give her some time. She probably has to recover."

"I don't think you get over being crazy."

"I meant she'd have to recover from you. Anyway I never said she was crazy. I don't think she is."

"I do. You can always tell by the eyes. That and everything she says. Pure craziness, crazy in the braincase, crazy in the heart."

"Mercer," Beth-Anne said, and she waited until he looked at her. Then she said, a little too seriously, "Never assume you know what's in another person's heart."

"I gotcha," he said, and dialed the number for time and temperature to throw her off.

He tried calling Evelyn again the next day. Nothing. The day after that, she picked up on the ninth ring, with a "Mmm?"

"It's Mercer," he said. "Elmer Mercer? I wanted to know if you'd like to see me again. You don't have to. I thought you had a nice time is all. Are you there?"

"Helllllo?" she said. Her voice sounded like it came from the bottom of the sea.

"Yes, hello? I thought maybe something happened to you, or you went out of town. I couldn't get hold of you."

"I . . . said . . . yesss," she said, as if she had a vicious headache.

He thought for a moment. "Okay, sure. Look, meet me back at the Agora, tomorrow night at six. We don't have to eat there, but just meet me." He stopped a moment to listen, but he couldn't even hear her breathing. "Evelyn?" he said. "Evelyn?" But she didn't answer. He waited and waited. Finally he hung up. Had any of it gotten through? What kind of a mood was that?

And of course, he sat outside the restaurant, the fancy Agora, feeling foolish. He was all dressed up, everyone could see that walking by. Even the dishwasher who emptied a bucket of slop out the back door, even he stared for a moment suspiciously.

He waited an hour, then gave up. He didn't know why he did it, why he even bothered with her.

The next day, she called him and tried to apologize. "No problem," he said, whenever he thought he had to answer. After a while he stopped being angry and they arranged to meet again, but she still wouldn't give her address.

That evening he had her just where he wanted her. In the path behind the ball field, between the park and the fire station. It was overhung by pines so that it looked like a tunnel. Once you got inside the darkness, you couldn't see the trash or the beer cans, or the syringes. Sometimes he heard voices, people moving away from him in the darkness, but he kept walking. He was a large man, and he wasn't afraid.

It bothered Evelyn though. "What if we run into someone?" she said.

"Who?"

"Kids or someone."

"I'll tell them it's past their bedtime."

"What about muggers?"

"As long as they don't shoot. Course, if they shoot me in my good leg it might even out my stride." He was grinning but of course she couldn't see it.

"You don't worry about anything, do you?"

"And you worry about everything. Why don't you leave all that for when it doesn't matter?"

"And just when is that?"

"When you're dead and gone."

"That's the only thing I'm not worried about," she said.

"Yeah? Why's that?"

"Because I know I'll live again, only in a different life, a better one than this."

He stopped in the middle of the path at the darkest spot, and reached for her arm.

She pulled it away, saying, "Yes, that's what I believe, that there's something waiting for me after death. But only if I keep living, if I keep torturing myself by living."

"That's what life is to you? Torture?"

"My life."

"And then you'll go to your reward," he said.

"Don't you make fun of me." She was angry, and he reached for both arms this time.

"Look," he said when he found her wrists, and then her hands. "It's just the way I talk, I put my foot in my mouth all the time. Here." He took her in his arms and was surprised to find that she let him.

She said, "Were you supposed to do that?"

"As opposed to what? What were my choices?"

"Sorry, stupid question. I always ask stupid questions. You can tell me to shut up if you want."

"I don't." He didn't know what else to say, so he started to relax his hold.

"Don't," she said, and pressed herself to him. For a long time they stayed like that and it was great. It was quiet, and they could barely hear the city around them. Then she said, "What would you do if I never wanted you to let me go?"

"What? Well," he said, "if I cared for you, that is, if you and I were an item, then I'd hold you as long as you wanted. If that's what you mean."

"And you would never leave me?"

Now he really knew they were on shaky ground. "I don't know, but whatever troubles you've got, maybe you're taking them a little too serious. People can get over things."

"I can't. That's why I've never been good for anyone here."

"Here? Here where?"

"In this world."

"Jesus," he said. "It's the only world we've got."

"You don't think I'll live again? You don't think I can make it through? Or don't you believe in other worlds?"

"I'm not saying there isn't another world, but if there is, I'd like to know how to get there."

He had bothered her now. He had made her angry, and yet she hadn't moved. He didn't know when he might have a woman in his arms like this again. Not for a long time. Not one that didn't want to squirm away and go do something. He caressed her head and gently pulled it against him.

"The other half of the time," she said, "I don't believe any of that. Which is why I know I'll kill myself. I don't know when, but I will."

"Jesus," he said, thinking, maybe she wanted him to think she was crazy. It could have been a game she was playing. Or maybe she really was. How could he tell? He should take his arms away and step back, but the feeling was too much. His face rested on the top of her head, and she had completely given in. If it came to that, he might have to pry himself loose. Finally, just to see what would happen, he did.

"You don't like me, do you?" she said. "Of course there's no reason you should. I always jump the gun."

"It's okay. I feel a little awkward myself, but that's nothing to worry about. If it was up to me, I could stand here and hold you another ten years."

"Thank you," she said, but he could tell she didn't mean it. She was back to her original self. "Please take me back now."

"Suit yourself."

"I will," she said, and she was cold, nothing but cold.

This time, when she was sitting in her car and he was holding onto the door, she reached to close it. He held it firmly. She pulled at it again, like she was about to explode some way or other.

Who else was there for him to go out with? Who else had paid any real attention to him in who knows how long? All he wanted was for her to say, I need you, just once like that.

"Evelyn," he said. "I don't understand you, but I like you. I want you to know I'm calling you again tomorrow, and I want you to answer the phone. Don't just let it ring. We'll get everything straightened out."

He let go and she sat there.

"Look," he said. "How do you know you'll never be happy?"

"Because I don't like life. I don't like to work, I don't like recreation, and there's nothing I like in between."

"You don't like to paint?"

"Not enough to live for."

"What about if you met someone? I don't mean me, but someone better."

"You do mean you. No one can make another person happy."

"Fine," he said. "Jesus, you're a case." She drove away without looking at him.

Sometime during the night he heard a fluttering at the door. He sat up in his easy chair with that sense of something important having passed. It bothered him so much he got up and went to the peep-hole. He put his eye to it but there was no one in the stairwell. He put his ear to the wood but couldn't hear anything except the wind. He opened the door and there was the note suspended by a single line of tape, twisting in the breeze.

He took the note inside, then sat down in the chair to read it, partly afraid and partly excited. It was the middle of the night, and anybody could have put it there, but he knew who had.

"I NEED YOU CALL" is all it said, and it certainly was her note. He had never seen her handwriting, but the shaky scrawl and the intensity said it was her.

He called and called but there was no answer. Maybe she was out driving around, hadn't gotten home yet, he thought, but after an hour he gave up calling.

He was so angry he wanted to wreck everything in his apartment, but he had seen that in too many movies, and always thought it was stupid. Instead he went walking in the tunnel under the trees, and every time he heard a noise, he said, "You better get the fuck out of here before I break every bone in your face." Once he laughed when someone scurried away in the darkness.

On Saturday, he hung out in the grocery store, waiting. After two hours, he found her in the canned goods picking out lima beans.

She didn't seem surprised to see him but she seemed a little scared, her red eyes large and round.

He said, "You know me well enough by now to see I'm nothing dangerous. I'm a mild-mannered accountant and I have a little bit of a temper, that's all. I'd like to come to your home."

"I'll come to yours," she said.

"You know where I live?"

"You got my note, didn't you?"

So she did come over and they had it, their first night of love. He watched her breasts swaying over him, her eyes open, the frown on her pursed lips. It was the look of someone concentrating, kind of like she was searching through a drawer for a postage stamp. He made her stop, and pulled her down beside him. Her eyes were wide then, wondering what she had done wrong, until he got on top of her and began making love to her that way, kissing her, kissing her breasts and her mouth and her neck, her arms and her fingers and her face. She had closed her eyes and he could feel her fingers clenching and unclenching, her heels digging in.

It wasn't perfect and it didn't go on for as long as he wanted, but when it was over, he held onto her and kissed her and listened to the music on his stereo. It made him think of the city and how different everything was in the city. There wasn't anywhere to run, only people cooped up in the same little boxes. How much an open window meant, the trees in brick planters and the sidewalks after rain. You could buy anything you wanted, hear any music or read any book, but you were always alone. Even now, with Evelyn, he was alone because in the morning she would leave. There wasn't room for her to stay. There wasn't room for anything, not one thing more than he had.

"I like you, Evelyn," he said, stroking her hair, and he added, "I just wish you weren't so down on everything." What he meant to say was he loved her, and if she would only smile one honest time, he would make room for her no matter what.

For a long time she didn't say anything. Then she said, "How can you like someone like me?"

"Maybe I can make you happy. Ever thought of that? How many guys you been with? Dozens? Two or three? You haven't been with every man on earth. How do you know I'm not the one?"

"I told you a person can't make another person happy."

"You're not dead yet, Evelyn, you got some life left in you. How do you know tomorrow you won't get over this?"

"You don't understand, do you?" she said.

"What, that you like being unhappy? That you'd do anything in the world to keep yourself unhappy?"

She stared at him for a second, in as much shock as he was for having said that, and he wondered which one of her would answer, the meek or the fiery.

"I don't like being unhappy any more than you do," she said. She got up out of the bed and began searching for her clothes. He got up too and started grabbing them up. She had her bra in her hand but he had her pants and her blouse and panties, and he was bending down for her left shoe when she started hitting him.

"Give me my clothes back, damn it what are you trying to do, keep me prisoner?"

"I don't want you to leave. I want to tell you I like you, and everything will be okay."

She moved away from him, not wanting him to see her face, and threw off the hand he placed on her shoulder.

"Sorry," he said. "I don't know the right things to say. If I didn't like you I wouldn't say anything. I'd just shut up and let you go."

"No you wouldn't, and you know why? Because you keep thinking you can rescue me. That's what you want, that's what you live for. Like that neighbor lady you saved, and your sisters, and probably every other woman in your life, and it didn't do a bit of good, did it? You limp around alone just like anybody else."

"So what?" he said. "What if it's true? Is that supposed to be a bad thing? Am I supposed to apologize for it?"

"No, you're supposed to suffer for it, and you will." She was holding back tears and tearing clothes out of his grasp. He sat down on the bed while she dressed.

"I'm supposed to suffer because I like women? Because I like you?" he said.

A minute later she was gone.

Sometime during the night he heard a fluttering at the door. He sat up on the couch with another feeling of something important passing. He got up and opened the door and there was a note suspended by a single line of tape, twisting in the breeze. It was the middle of the night again, and there were twelve white roses in a vase on the floor.

He took the roses and the note inside, excited once again, but partly afraid. The note said, "I'M SORRY. I TOLD YOU IT WAS THIS WAY."

What did that mean? He called and called but there was no answer. He was angry again. It was a roller coaster with her. Everything had to be up or down but nowhere in between.

He picked up the phone one more time.

"Hello?" said the calm and friendly voice. It was his assistant, Beth-Anne. He was hoping maybe, just maybe Beth-Anne had Evelyn's address. She gave it to him reluctantly, and she said, "I'm sorry I got you into all this."

"Don't apologize," he said. "I don't know why, but she's got her hooks in me. She'll talk to me tonight or I'll bust down her door. I'll let you know what happens."

He hung up and hurried down to his car. He wasn't taking no for an answer. He would tell her he loved her this time, no matter what she said or did. If she didn't love him back, that was her business. At least he wouldn't let this opportunity go by for nothing. The problem was, he had this feeling she had done something terrible, and he would never have his chance.

He ended up knocking on her door, and banging when knocking didn't work. Nothing. There was a dim light inside and he could see her car parked in the driveway below. What was she doing to him, hiding? He yelled and tried the door but it was locked. A light came on in another apartment. He ignored it, climbing to stand on the stair railing and look into her living room. The curtain was partly open but all he could see was the hallway and part of her kitchen. He put his hands on the brick and eased out onto the ledge, balancing dangerously so he could look into the next window, which was her bathroom, half expecting to find her in the bathtub with her wrists open and drained of life, but it was empty. He banged on the window and tried to open it, but it wouldn't move.

The front door burst open on the second kick. He ran in and she was sitting at her dining room table, not surprised at all, apparently. There was music on, and the light from only the one lamp. A glass of wine sat in front of her, untouched, and the music was something soft and bittersweet. She glanced at him with a pained expression and looked back down at the surface of the table, as if it held a clue to the mystery.

"I thought you might have done something," he said.

"Shut the door please," she said.

He shut it and came over to her.

"Your note, I didn't know where you were, I thought you might—" but he let the sentence hang there, not wanting to offend her.

"You thought I killed myself?" she said, looking up angrily now. She held out something for him to see, shaking it in his face, making it rattle like a maraca. It was a pill bottle, and it was full.

"I'm glad you didn't," he said, wanting to touch her, to at least put his hands on her shoulders. "Because I worried, and I—"

"I was trying to figure it out," she said.

"Figure out what?"

"What it would be like if I was," she said.

"If you were what? Dead?"

Now she looked at him with her mouth open, and he could tell she was thinking, long and hard before she spoke. "Happy," she said at last.

Brad lives in Charlotte with his wife and two dachshunds. His first novel is finally creeping toward its inevitable end, and so is his MFA degree at USC-Columbia, where he had the privilege of studying poetry with the (still) irrepressible James Dickey. With degree in hand, he hopes to teach creative writing somewhere, anywhere, someday.