Page 4

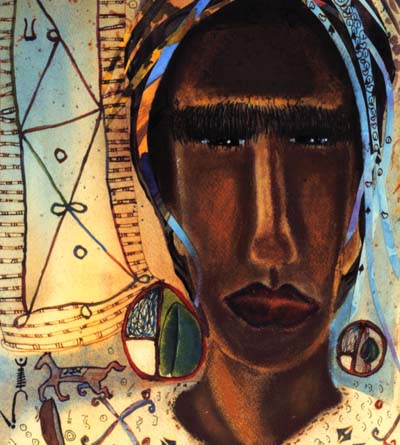

"Hope,

There is Still Hope, and So We Call Her Hope"

mixed

media, collage 17" x 11"

The painting of "Hope, There Is Still Hope, and So We Call Her Hope" was given to me as part of a series of sacred messages. The guide whose mortality this represents is one whom I have named Hope, There Is Still Hope, and So We Call Her Hope. I have asked for stories about what life was like for her as a mortal woman and afterward. She lived more than six thousand years ago in a dry, plateau area which was warm enough for her to neglect clothing most of the time. Nonetheless, after she was given a robe and tunic as a tribute from a very respected member of her clan, she wore her tunic every day. Hope was dark-skinned with long, straight black hair. One of the most distinctive features of her people was their eyebrow hair, which shrouded the eyes like short, straight bangs. Their faces were long, with pronounced occipital bones, long thin noses, and narrow cheeks. They had no mirrors, so Hope drew, through the facility of my drawing, the face of her apprentice. Following her instructions evoked several epiphanies about myself. First, I found myself fighting the urge to create high, Indian cheekbones. Even as she watched, my hands reached into a curve below the eye, instead of above it. Secondly, I had never noticed occipital bones, and did not have any sense of having seen them. When I was on a trip to New York City she pointed out several people with her sort of occipital bones and forced me to practice shape, light, and shadows that went above the eyes, and not below the eyes. Third, I could not reproduce dark brown skin. This I know to be a reflection of the racism of our time, that standards of humanity in the United States require white skin with certain flesh tones which African Americans and dark-skinned Indians do not have. It was with new humility that I recognized my submission to obey in images what the U.S. permits in ranges of skin color. That is a disgrace to my Native heritage, and I have suffered with the self-knowledge.

There are many elements in this painting which Hope explained about her life. The rectangular area in the upper left depicts the last phase of rug design which she was entitled to create. She wove saddle blankets for yaks which were used as pack animals by her people. The process of making a saddle blanket and being a weaver of such blankets required a psychic, albeit wordless bond with the animals. The animals were arrogant, and dominated the people in small ways by biting, spitting, and refusal to work if anyone displeased them. Hope became the peacemaker in many a dispute between humans and yaks during her lifetime. She was taught both by a mortal weaver (an old man) and her own spirit guides to weave the blankets. She was also taught by the yaks themselves. Every night she brought her weaving to the herd for whom she was making a new blanket. First she showed it to the animal who was to receive it. The yak would inspect it by nosing each stitch, sometimes using its tongue to explore the roughness of the texture. Since the blanket was usually the only one the yak would ever have, it was important to the animal to know that it would not suffer from abrasions caused by lumps in the weaving or sharp edges in the threads. Besides the owner yak, Hope also showed the blankets in construction to the head yaks. There were usually two, a mated pair. The herds themselves chose which yaks were their leaders, and most of the time it was the oldest pair, but not always. Both of the head yaks would inspect the blanket with the same care that the owner yak did, and sometimes they found mistakes or rough spots that the younger yak did not. Only once did Hope ever weave a bad blanket (her third), and she remade one for free as soon as the yak made her aware of its discomfort, mentally signaling her every time she passed. That was one of the ways she endeared herself to the yaks.

The design itself is one which Hope's immortal guides taught her. She started with the "X" at the bottom of the blanket. Her first blanket had only the "X" without a border or any other decoration. About two years later she was empowered to add the right side of the infinity sign on the "X". A year later she was told to add the left side. When that happened, the head yaks of that particular blanket signaled all of the rest of the herd to inspect the design. There were only twelve yaks, but Hope felt as honored as if thousands were applauding her ascension in her sacred training. Each of those marks signified a new stage in the sacred teachings she had come to understand. She began as an apprentice weaver when she was about 12, and died when she was 58. When she was 32 she was allowed to add the border of parallel lines (sans hash marks). Five years and 17 blankets later she was permitted to insert the triple hash marks between the parallel lines. Each of these stages was applauded only by the yaks. When Hope was 48 she achieved inserting the upper extension of the upper "X". When that happened she was accorded recognition by a special ceremony in her clan. When she was 55 she was told to add the "U" shape to the upper half. When that occurred, she was celebrated by the entire community in a large feast which lasted for a week. It signaled her sacred rapport with the yaks in a way which transcended the need to be immediately present to the animals. In other words, people of other tribes could order her blankets with full assurance that the rug would be perfectly suited in every way to the yak to receive it. She wove six such blankets before her death three years later. Because of the prestige of her ascension in the sacred to this level, one of the blankets for a distant tribe was used as a gesture of peace between two formerly antagonistic peoples. The head of that tribe gave Hope a pair of scissors (the first she had ever seen) made partially of iron (the first metal any one in her tribe ever saw). It was such a rare and coveted gift that she slept with it beside her head every night. It was awkward to use, and much duller than any knife Hope had ever owned, but she insisted to everyone that it was a miracle in the latest technology. She struggled to cut only one or two fibers at a time with the scissors, and put them down as soon as there were no witnesses. The head of her tribe often brought visitors to view the scissors, the blankets Hope was weaving, and Hope herself. Until that time, she was never given any notice by anyone, as she was born of a commoner family in her clan.

Hope, There Is Still Hope, and So We Call Her Hope died in peace at the age of 58. She was thought to be very old, but not the oldest one of her tribe at that time. She died alone, for it was the custom of her people that men and women dwelt in separate houses. She had four husbands, each of who was chosen for her by her mother to father her children. The system ensured that each child would have a father who was required by their code of ethics to provide at least one meal a day until the child was old enough to work for himself or marry. A capable man could have as many as three wives, and rarely one had four. One of Hope's children fathered four children, but was officially ousted from the community for failure to provide for them. He was capable of providing for only one, and did not heed the injunctions of his mother or clan leaders to abstain.

When Hope was near death the yaks knew, and seemed to grieve for her. One day about a week before she went into her final bout with illness, the head yak of the main herd in the tribe beckoned to her from the field. She had often found time to spend caressing this yak female, especially when she was called upon to resolve a human/yak dispute. When Hope was beside her old friend, the yak, in an unprecedented action, rested her head beside Hope's head for a few minutes. They could not exchange word thoughts, but the love and loss expressed by the yak were unmistakable to Hope.

Hope died of problems related to poor circulation. She could not warm herself, and suffered from a bone-chilling weakness. Shortly before her death, she declined into a final illness and coma. When Nancy heard the description of Hope's lifelong symptoms of weakness particularly during pregnancy, she posited that Hope might have suffered from gestational diabetes. Hope had four children, and during the pregnancy of each she was bedridden for four or five months, followed by a month of exhaustion after each. She ate voraciously, and never seemed to have any body fat. Although she ate big meals every day, she often felt that she was starving. Her diet consisted primarily of a mash made from a grain product which does not exist in Alaska. Hope and each of her children each ate about two pints of the mash each day. On rare occasions she was given salted dry fish, which she ate greedily.