|

|

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Oct/Nov 2015 • Nonfiction |

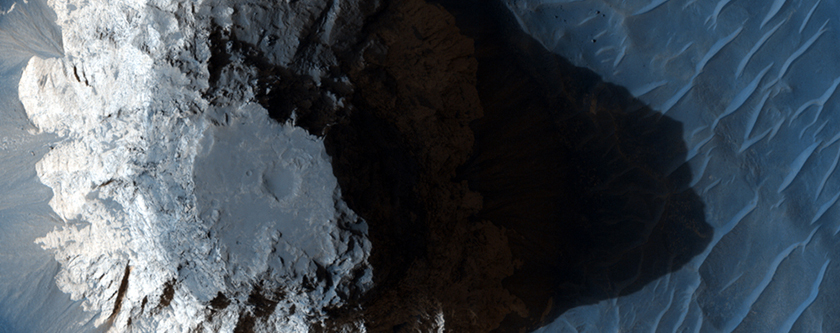

Image courtesy of NASA and the University of Arizona

"All it takes is three guys bringing their wives to ruin the whole fuckin' trip."

—Passing stranger on Las Vegas Blvd, to his female companion

Las Vegas seems worse off every time I visit, like an aging uncle whose vitality and humor amazed me 15 years ago, but who now drinks Schlitz on the couch all day, reeking of moldy Winstons and burping between dick jokes. It's a more festive version of what I imagine North Korea to be, trying its best to convince you everything is peachy keen, that everyone around you couldn't be more excited to be part of the jamboree. In reality, though, it's the Pleasure Island of Pinocchio's nightmares, where people wear three-foot booze-laced slurpees like feedbags and make mosh pits of the sidewalks among the tourists and their Canons. It's a place where parents poorly mask their boredom-induced getaway as a "family vacation" by dragging a couple toddlers past the naked pirates and Chippendales. Admittedly, it's better than internment camps. I presume. This is my third time here.

Despite its Fellini-ness, I got engaged here, about nine months ago. The proposal was indeed spur of the moment, but not in the assumed Vegas tradition of drunkenly promising my life to some floozy I met at a rave. Not that I'm the kind of guy to go to a rave, as demonstrated by my use of the term "floozy." My fiancé was on a work-expensed trip, so I tagged along and we stayed a few extra days, choosing the sweltering sand and neon over New York City's sweltering steel and asphalt. I'd been carrying the ring for months, waiting for the right moment, and it finally came after a blissfully relaxing day by the pool under the desert sun with a pitcher of tea and a bucket of beer. So it was more by happenstance that we got engaged in Vegas. Luck, I should say. Odds were roughly 1:364.

She's in Fort Lauderdale this week, in a rented house on the beach with eight other girls—none of whom are floozies, as far as I know, although I can't vouch for their pasts—at her long-awaited and dutifully planned bachelorette weekend. We're getting married in three months.

I've come back to the sparkling neon jungle of the Mojave desert for a fiancé-less jaunt through the most lustful city in our crazy nation, to see the long odds and longer legs, burlesque zip-lines and gyrating pelvises eye-level on every Fremont bar. I'm here for one last ride in the sinful cockpit of America's bachelor paradise.

And I'm here with my parents.

It's their 37th wedding anniversary, and Pops is retiring next week after 45 years with the phone company. It's also his 65th birthday a few days later, right before Father's Day, which is the day after Mom's birthday. So I'm not here, necessarily, to partake in the sin and lust and naked bungee jumps, but to gawk and point from a distance with my Christian, rural Virginian parents, while my beautiful fiancé lives the life I want in sunny southern Florida. Because I'm a good son. Also, hey, free trip to Vegas.

On the plane from Chicago I sat next to a married couple who didn't speak to each other for the entire four-hour flight. The husband watched two movies on his iPad and read while his wife's eyes glazed over, occasionally flitting to the in-flight movie when she wasn't reading SkyMall or playing some 8-bit iPhone game that 25 years ago she'd have screamed at her son to turn off and go outside. They didn't speak when we landed, nor when he retrieved her carry-on, nor even on the tram to the concourse of McCarran International. But the frightening aspect of their silence wasn't that it felt tense or angry, as if they were barely holding back an eruption. It felt normal.

My parents are not like this.

The cab driver from the airport, who looked like a hippie shop teacher and had the voice of John Madden and Jeff Lebowski's lovechild, complained the whole time about his family, who constantly asked to borrow his money. "Borrow," he informs me, taking both hands off the wheel to properly air-quote, "is a term I use loosely. I'm not giving you $80,000 for your husband's second Ph.D.!" he continued, watching me in the mirror to make sure I was paying attention, turning around at the stop lights. "Fuck, man. I told 'em immediate family, I'll help out with comps and shit like that, 'cause I can do that. You know? But no more of this in-law shit." He seemed to calm for a moment, tucking a greasy scrap of hair behind his ear. Then he remembered more evidence. "She's been married three times," he said, spinning around again and holding up the last three fingers on his right hand. "And she even got pissed when our step-dad starting seeing someone six months after Mom died. He's fuckin' 94, Karen! Right? If his dick works we should be cheersing him!"

Shockingly, he was not married. I couldn't muster the gumption to pry into his surprising financial situation. Nor why someone with such wealth and apparent Vegas prestige spent his days shuttling tourists from the airport into the fray. I was also afraid that more questions might encourage him to keep yelling.

Unlike the mute couple on the plane, my parents had plenty to say. As if they'd just stepped out of the freak show tent, I was regaled with mock anger at hotel mishaps and overly dramatic impressions (from both of them) of zigzagging "drunkards" on the Strip, and the "sireens" going all night long. Yes, Mom knows how to spell it, but being intelligent isn't going to make her take the r out of "warsh," either. She theorized that "something must be going on, 'cause I have never seen so many people." I assured her there was no offseason in LoonyLand.

"We just wanted to come and finish up what we didn't see the first time," she told me later, sipping a frozen margarita and shrugging her sun-freckled shoulders when I asked why they chose Vegas for their annual trip. "I doubt we'll ever come back." There was nothing malicious in her ambivalence. They'd visited once before, walked through the hotels, people-watched, booked a tour. They don't gamble, and I have to coerce them into having a drink with dinner each night, mainly so I don't feel so guilty about having three. She spoke about Vegas in the same tone I assume the mute wife would have spoken about her marriage. They'd squeezed everything out of it they could, and were content to cruise for the rest of their time here, gazing at the passersby, maybe taking in a show.

My parents never have a lack of things to talk about, even (and especially) when they aren't talking about anything. They constantly practice their calls-and-responses, surreptitiously pointing out odd landmarks or people the other might appreciate, in this case through a shared provincial astonishment at the kookiness of Vegas. John Gottman, the professor emeritus and marriage researcher who was the subject of an entire chapter of Malcolm Gladwell's Blink, calls these "bids." He claims they are basically a way for someone to connect with their partner, to share a moment, in the hopes of having the connection, or at least the attempt, acknowledged. Perhaps lovingly so. My parents are its most avid practitioners.

Pot-bellied drag queens, crackhead Elmos, card-clicking hooker hucksters, Willie Nelsons who somehow look worse than the actual Willie Nelson, floozy gaggles, stupid t-shirts, penis goblets, and janky souvenirs. Each spectacle prompted a quick gasp and a subtle, "Tommy..." from Mom, or a nudge and a furtive, "Look a' here," from Pops. And every instance received a dutifully silly and aghast reply. "His poor mother" and so forth. In other words, they make conversation when there is no conversation to be had, in the form of snippets, fleetingly shared to be bonded over later. "Remember naked Elvis, Tommy? Lordy, what would Pastor Keith think..."

There is a consciousness, though, to what they're doing, or at least a subconscious acceptance that they're not immune to the caricatured foibles of marriage. They take them casually and with tongue in cheek. For instance, Mom's Nag Voice. "Now we're not gonna have any laggin' behind around here," she tells Dad, but in an octave higher than normal and with a cartoonish, henpecking tone. She knows she's being the prototypical Nagging Wife when he's dawdling, looking at the funny hats in the window or listening to the Richard Nixon Barbershop Quartet. But she hams it up. She makes a joke out of it and wraps her arm around his waist with a loving squeeze.

But she's serious. Walk faster, Tommy.

Pops is less self-deprecating, yet still very much an American Boomer father; two kids, various pets, house in the suburbs, retired after working 45 years for one company, all of which has given him the stoic patience of a comatose monk who wakes up only long enough for the occasional dad-joke. Probably something involving a cored jalapeño, or some other "holy vegetable."

In other words, he has become un-naggable. Perhaps he was born this way.

Growing up, I thought this was a weakness. After a wrong turn on the interstate or picayune marital spat, when Mom wouldn't just let it go already and the Nag Voice had long since disappeared, I would think to myself in the back seat of the Astro that marriage seems like such a pain in the ass. I saw myself as too prideful to roll over and let my future wife just keep carping on and on and on. How could he just sit there and let her hound him like that? Reply! Retort! Defend yourself!

It was rare when they actually argued, though. Or if they did, they hid it well. I've never heard one of them raise their voice to the other, and they're the kind of middle-aged couple who hold hands in the mall and sporadically smooch. I'm sure they'll be adorable fogeys. But when I was a child and witnessing the niggling warts of marriage that every young man dreads, my gender-limited perspective only allowed me to sympathize with Dad. I could only see the man of the house emasculating himself before the woman. And the only reason she was haranguing him was because he had gotten mad at something else. What foolishness is this?

As an adult in a long-term relationship with another human being, I get yelled at regularly, too. Sweetly, of course. But I'm old enough to understand that almost every single time, I deserve it. And on the rare occasions where it's not justified, I know that she's beautiful and strong and mature and humble enough to apologize later. But those cases are rare. Most of the time it's justified. I'm moody, quiet, loud, prideful, selfish, catty, flatulent, and forgetful. But in my defense, so is everybody else. As an adult in a long-term relationship with human beings in general, I have enough experience to acknowledge and accept that every single one of us is, at some point, an asshole. We're disgusting. We're rude, priggish, greedy, stupid, spiteful, hateful, and boring. We start wars and perpetuate slavery. We rape and torture. We pick our zits in public and condescend to waiters. We're mean to animals. In a purely pragmatic sense, the absolute best of us are merely the least worst.

An implicit acknowledgement of marriage—one nobody mentions because it's not romantic—is the unfathomable improbability of finding another human being whom we can perpetually tolerate for a few days at a time, much less for the rest of our lives. Recall the feeling of falling in love, the drunken bliss of discovering someone beautiful, who turns out to be funny, then smart, then kind and compassionate and loving. The worst thing you can find about them is an occasional impatience or morning breath. My fiancé and I—at least until she reads this—have discovered not only a mutual, synergistic amazement of one other, but also that we're the least obnoxious people either one of us has ever met. So we're holding on for dear life.

Obviously, this is not to diminish emotional connections, shared experiences, and similar backgrounds, interests, and dislikes, all of which are equally as important to mutual lifelong tolerance as not being an asshole. But those are the romantic notions, the pretty truths that we rehash for our movies and Nicholas Sparks novels.

Here is an ugly one: I understand now that when Pops was getting barked at for cursing out the GPS, his stoicism was not a sign of weakness but of strength, much more profound and practiced than simply picking his battles. These "married" moments that young men dread, of nagging wives and diatribes, force us to question why we latched on to another flawed human being in the first place. And we answer the question honestly: because the fleeting irksomeness of the moment should remind us that this is as bad as it gets. That not only are the great moments great, but the worst moments, already few and far between, are actually quite tolerable. That she is, indeed, the least obnoxious person in the world.

I run this theory by Pops while we're topping 115 mph on Route 564 past Lake Las Vegas in a black Ferrari 458. The high noon sun gives a shimmer to everything, the sand and thistle and technicolor stone, the air itself and the draining lake, but especially the big, childlike grin on his face. Mom had surprised him with a ticket for World Class Driving, a company that lets American dads plunk down a grand to hurtle across the desert in a million simoleons worth of Italian metal. Between moments of trying not to piss myself or squeal like a girl in front of my father, I hear him chuckle.

"You think when she's giving me a hard time that I'm sitting there thinking about how wonderful she is?"

I would have said yes, tepidly, had he not dropped gears and floored it, trying to keep up with the Lamborghini in front of us. We eventually slow, and as my stomach settles back into my torso, he says,"Pfff" with a grin.

"When she's yelling and I'm quiet, it's just 'cause I know I'm right."

As if in preparation for this trip, I spent most of my teenage nights ravenously horny and unable to do anything about it, least of all because I was stuck in a bedroom adjacent to my parents. But those years of searching for nipples through the static-y lines of Cinemax did nothing to prepare me for the well-advertised notion that the hundred thousand people on the Strip below my hotel room were or would soon be getting laid, while I, in fact, was not.

This phenomenon isn't unique to Vegas, no matter how many sequined cleavages I pass or discount offers for 2-on-1 company I receive. I get lustful whenever I venture away from home, alone or otherwise. My fiancé and I are more salacious and uninhibited when we travel together, in hotel rooms or bungalows. So at the end of four lonely nights in a Sin City suite—between fits of anthropologically introspective masturbation—I come out with a sore wrist and this hypothesis: the newness is what makes me horny.

This is disconcerting to a monogamist.

The greatest marital invention never invented is a pair of glasses the husband wears that makes every woman other than his wife look like Rodney Dangerfield. Men rarely fantasize about relationships with other women. We don't pass a beautiful stranger on the street and think, "Wow, she looks communicative," or, "Man, I bet she compromises like a boss." But we're also not necessarily fantasizing about intercourse with other women, at least not the specific act. As adults with (hopefully) some sexual experience, we know and can recall what slippery flesh upon slippery flesh feels like. What we don't know, and try to stop ourselves from considering when the fiancé is around, is the beautiful stranger's newness.

We find ourselves dumbfounded, fantasizing of her nuances; the sounds and smells and tastes that we've never heard or smelled or tasted, and will never hear or smell or taste. But we have zero experience with her nuances in particular, and even their instinctual consideration is frustrating and futile. It's like fantasizing about what the moon smells like, or wishing you were a pterodactyl. We are aware and accept that those things can never happen. We can't even realistically think about them. Unfortunately, that doesn't stop us from trying.

The disallowance of "new experience" and the guilt of fantasizing about another woman produces in many men a natural skepticism of long-term commitment; we blame the carnal restrictions on the confines of marriage, as opposed to the fact that we have beer bellies and hairy backs. A fear of marriage allows us to convince ourselves that we might have been able to experience the beautiful stranger's newness, if it weren't for this damn wedding band.

But our man-boobs and pit stains and general imbecility are proof that our restrictions on carnal novelty have nothing to do with our jewelry.

It is no coincidence, then, that the Spanish word for "wives" is also the Spanish word for "handcuffs." The fear of sexual confinement is the bachelor's most commonly acknowledged anxiety about marriage, whether he's a swinger or serial-monogamist. Lust, at its essence, is merely our ingrained desire to "experience" (wink wink) something new, then another new thing, and another. It's evolution's raison d'etre: Make More Life (Or At Least Try As Frequently As Possible).

For those too weak or uncreative to refocus their primitive urges into a desire to experience new things instead of a desire to screw them, this often leads to infidelity.

I can hear Pops now: "Pfff. You think someone who's horny all the time should just travel more?"

He doesn't actually say this, of course, because of how weird it would be to discuss "horniness" with my father. The one youthful naivety I allow myself is the notion that my parents have had sex exactly twice, each time procreative, and somehow without any touching or funny business. But with Mom in the bathroom while Dad and I wait in the Italian marble lobby of a French-Canadian water circus, I see a beautiful stranger who makes me fantasize about being a moon-bound dinosaur.

I accidentally say, "Sweet fancy Moses," under my breath but a little too loud.

"Huh?" Dad says.

Dammit.

"That," I say reluctantly, jutting my chin at the beautiful stranger. She's taking a sip of chardonnay from a lucky plastic punch glass. "Does it get any easier to... you know, to see that and not..." He raises his eyebrows, curious to see how I'll phrase it. "You know," I say, bobbing my own like Groucho Marx. "Does it ever go away?"

His response surprises (and slightly disgusts) me. With a chuckle, he says: "Well, I hope not."

What? You hope not? I'd give my left arm for a pair of Dangerfield glasses, and my old man is happy just to catch a glimpse of a pretty lady, like he's driving past a sunset or a waterfall. It doesn't bother him in the least. In fact, he wishes it would occur more often and never stop.

When the hell does that happen? At what age do I begin to appreciate the beautiful stranger without primitively wanting her? Without at least instinctually fantasizing about her newness? Is Pops's sexual apathy a sign of maturity? Of acquiescence? Of laziness? Or is he just good at hiding it?

Maybe his eschewal of lust and simple appreciation of beauty is what makes him strong. And if I had to bet, I'd wager that that strength is one of those things I'm going to have to gain for myself, through experience and synergistic love. Figures.

Okay, fine. I'll learn for myself. But I'd still invent the Dangerfield glasses, because there's a mint to be made from the wallets of the weak. Just ask the cigarette companies. Or the lottery.

Like recovering alcoholics, men fight every single day against something their body is programmed to desire. We revere recovering alcoholics, though, and with good reason. Such abstention is a sign of tremendous strength. And they're justifiably proud of themselves. But if a husband has the opportunity to cheat on his wife and doesn't, there is no token. He's not revered, nor does he expect to be. But he should be proud of himself, too. Careful though; he shouldn't boast about it, lest he wants to return to bachelorhood, where he has no choice but to blame his lack of sex on his weird nipples and awful jokes, as opposed to his wedding ring. So maybe Pops's flippant appreciation of a beautiful stranger is simply a product of pride?

"Huh?" he says. "Alcoholics? Who's proud? Rodney Dangerfield?"

"Nevermind," I say, stealing one more glance at the beautiful stranger. "I'm an idiot."

"Tommy," Mom calls out behind us. She's standing next to a lithe, aqueous sculpture, bending backwards erotically. Her eyes are wide in playful embarrassment.

Dutifully, Pops responds, "That'd kill my back."

When I return to New York, a set of ring sizers are in my mailbox, sent by the company that's creating my wedding band. They're cheap aluminum rings similar to the size and shape of the one I ordered, designed to be worn for a day or two in order to ensure the proper fit of the finished product. I pet the cat and toss the junk mail on the table before plopping down on the couch, sizers tinkling softly in the padded envelope. I spill them out into my palm, their symbolism not lost on me.

Maybe marriage is like a wedding band; something you've confidently picked out and are excited about, because even if it's uncomfortable at first, you'll soon feel naked without it. Or maybe marriage is like Las Vegas; it makes you wish you had more money and freedom, but assures you that a transient, neon life is no way to live. Maybe it's like driving a Ferrari; if you cheat on the family sedan with a gorgeous Italian model, you risk losing everything from a single slip-up. Or perhaps marriage is like Rodney Dangerfield; you constantly fuss about not getting respect, but you know to your core that you're loved and adored a million times over, despite your beer belly, navel lint, and dad jokes.

My best guess, though, and I'm sure Pops would agree, is that marriage is like a simile: with a little finagling, you can get out of it whatever you're willing to put in.

I pick up a sizer and slip it on my finger, pushing it past the knuckle. Holding my hand at eye-level and watching closely, I dangle it limply and jiggle, checking to see if it fits.