|

|

| Jul/Aug 2014 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Jul/Aug 2014 • Nonfiction |

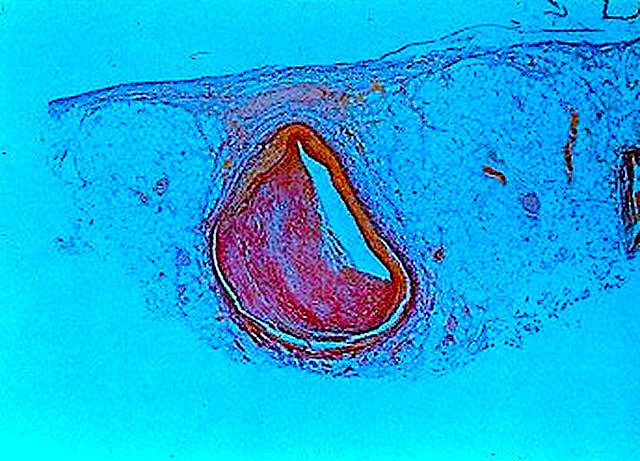

Image credit: Digital Media Database, www.genome.gov

There is a calm in the morning—waking up with the pain of leaving the warmth of my bed before I begin to drive and before the sun has even considered rising. I am 17 and needing sleep desperately as only a teenager can. I navigate by the clearest brightest stars and the essence of sleeping woods while the whir of truckers steadily hums past the breathing warmth of my car on the highway. I doze and coast along the lanes, letting myself linger in my haze, knowing my car will find its way. It's the same kind of calm that will allow my car to crash into a telephone pole at a full 45 miles per hour, cracking my sternum, a year later. Now, deer peek out of roadside trees with eyes that, like the street signs overhead, pop with the flash of my headlights. I can smell the dust of the objects in my backseat and trunk—a mustiness from their various cycles through the damp mornings at the markets, where dew forms on books and drips down glass. The chill of the dark penetrates my layers straight into my bones.

The gravel crunches as I pull into the lot. Hundreds of crickets tweet outside my car window as I settle in under a large familiar oak tree that will protect me from the midday sun. Last year, right in front of my table, one of its large limbs came crashing down at noon, decapitating a dealer. Still, I return to it like a second home and turn off my engine to sit and wait. It will be hours before the light comes. I curl up in my front seat listening to the radio voices of construction workers calling in to find comfort in the fact that others are awake, too. Sipping on a coffee, dozing slightly, I hear other cars pull into their spots. Jacketed dealers saunter out to adjust their tables according to their own rituals. They place heavy metal objects on top, clear enough space to walk in between, and push them close enough to prevent others from doing the same. Spreading sheets, cloths, and newspapers, they stake a claim on the area that is rightfully theirs while trying to justify the early commute.

As I hide and listen to my radio on low, people emerge one by one and start moving around the market like gently stirring molecules. Customers pop up and walk aimlessly in the dark, searching but not knowing for what. Bouncing off tables, they appear and disappear under dim streetlights illuminating the aisles. Sellers begin to buzz, start small conversations, and avoid unpacking. They are waiting for the men with flashlights to come around and shine them in their cars, front seats, trunks, looking suspiciously and expectantly at stacks of boxes while asking fervent questions. The buyers hope to get a positive response to just one of their queries from someone, anyone. "Got any jewelry? Coins? Toys? Any dolls today? Guitars?" Later in the day others will come looking for keys, Boy Scout memorabilia, cameras. Unlike the early eager vultures, the late morning guys have a consistent calm gimmick, an identity they show in their clothes and the way they ask questions without expecting answers. They wear vests of patches and advertise their wants on their hats. These men are noticed as much for the time they arrive as for what they wear, doing the rounds day after day and week after week at different markets. I know them as friendly familiar strangers looking more for companionship than merchandise: when you have what they want, they often lack the money to buy it. I have many friends of this ilk that collect around my table during the day. There's broken gold guy, record collector, and amateur photography connoisseur, none of whom ever buys anything from me. They tease me about my merchandise: it is old, dirty, and unpriced. They've known me from the time I was six years old. I've felt myself grow and change while they've stayed the same, telling me unchanged stories, smiling just as quizzically as I tell them mine.

"Any ummmmm," they ask me again.

"I think so, let me check."

They get excited. In the early morning before sunrise, it is all in the timing, the slow reveal. It is a burlesque show, a tease contingent on the excitement I can create for the flashlights. I can't put all my goods on the table right away. It's not exciting, it's stale. There's no anticipation, no chase. I have to wait, unpack slowly, and hook them with a good eye-catcher like a guitar or a cut glass vase. It has to be something not too expensive but just expensive enough, large enough, tempting and weird enough: antique fishing rods, a crossbow, an abstract painting. I hook them to get them excited about what more they might get to see inside my boxes, under the sheets, and in the car. I reserve a few things and pull them out only when they ask for them. They came from grandma's attic, my old neighbor's basement, or an auction in the country. This stuff is authentic. I have to slowly tease, pull out, and carefully unwrap fresh merchandise along with stuff I haven't been able to unload for weeks. The bad looks good when it's placed right and adjusted just so in the midst of beauty. If I've got great tits, they won't notice the scar on my navel. My pasties distract enough for me to convince them old merchandise is new.

I never price anything. Instead, I read the customers. After I catch their interest, I hook them with numbers. Numbers come out in batches. Depending on who it is and how I feel, the numbers ring out low enough to get interest from them and often the others hovering nearby. The more they buy the more expensive it gets cause when I start low they convince themselves I am giving it away. I obviously don't know what it's worth and am underselling, desperate, young, pretty, and dumb. They may have known me for 20 years, but the buyers are dying to be convinced of these things, and my cool demeanor convinces them.

Like my grandmother I always wake early, take a shower, apply make-up, do my hair, and compose myself to stand out among the dirt, and they smell it on me. They believe they are putting one over on me, that they know better than me, and this time, they've got me. I sell things cheap, really cheap, less than they are worth to start, just like a drug dealer. This is how I get them hooked. They will make stacks of stuff and pay anything without question. As they feed, others feed. There's no time to pause or think, or the others will go for it. They pile. This is the feeding frenzy I have to catch and maintain for as long as I can. After the long, slow reveal, I let it all fly. I talk. I never make eye contact. I concentrate on my unpacking as they pile up, push, drool, grab, grab, grab, as the numbers quickly fly off my tongue 5, 30, 100, 10, 7, 7, 7—I'm in a 7 mood. Others buy things they don't want cause it's so cheap, maybe they can get a piece. I take their piles of cash and don't even bother to count it, shoving the piles in my pocket with the other piles. I thank them, flash a huge smile and move on to the next buyers who are just waiting to give me all they've got. I don't care; money is nothing to me. Merchandise is nothing to me. There will be plenty of time for details later. The bills pile as I run out of grocery bags.

I clear half my merchandise in 20 minutes, and then it is over; they are gone and the sun has risen. I step more slowly now to arrange, rotate, clean up, and check that the piles in my pockets are still there. I have a long morning ahead of me. No rush now, I take my time. I am naked. It is six a.m. and time for a new cup of coffee. I sneak into the front seat of the car and close the door. I unfold the crumpled bills, carefully arranging them in a neat stack: $647. I will most likely make only another $50 over the next six hours. I settle in.