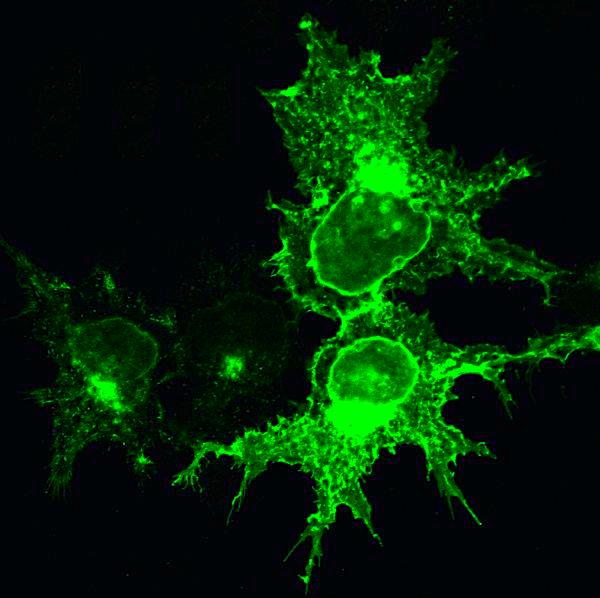

Image credit: Antonio Velayos-Baeza, University of Oxford, Digital Media Database, www.genome.gov

I fueled up the Nashville bus and coiled the hose back into the ground trap.

The diesel spume whipped across the drive-way. John Selby gave me a wave as he backed his scenicruiser out of the parking slot. He was careful not to hit the caved-in, iron-yellow railing running along the whole side of the Arizona Bar, an establishment which had no one in its history or ownership in any way connected to that state as far as I knew. Before he hit second gear, John touched his air horn, a tip of the hat to Rhonda, the Post House waitress who spent her days in pointless longing as she waited for John to get a divorce and marry her. An occurrence about as likely to happen as John bringing his bus in on time, something he had never done in nine years.

Back in the locker room, I used some Lava soap and talked to Murphy Man about his arthritis, which he swore got better when he took a daily dose of turpentine and sugar. Out in the baggage room, I hit the clock and waved toward the baggage clerks.

I crossed the parking lot past eight buses and stood by my old green pickup, watching some November geese flying high in a vee.

Out on South 41, I got behind a Peabody coal truck and watched coal grit looking like black sand hitting my windshield. A guy in a suit and tie roared by, his face all bunched and his shoulders tensed. Probably had to go home and hang dry wall or get on the phone and invite people to an Amway meeting, just the kind of thing you wouldn't mind killing yourself over.

On the radio Merle Haggard was singing "If We Make It Through December."

When I went over the bridge spanning the Ohio river, I saw driftwood in the muddy water. The river would be in my bottom fields by day after tomorrow. I'd have to take Buster down and shell out some corn for the pigs before it got soaked and rotted.

Ten minutes later, I stopped by Toby's Cut Rate Liquors. Toby was already heavy-lidded, sipping out of that bottle of Wild Turkey he kept under the counter right beside his 12-gauge Remington.

I grabbed two quarts of Heaven Hill vodka and gave Toby a twenty and got my change.

"Don't you break that seal until you get home, Moon Man," he told me with a wink.

"I hear you, Son," I nodded.

The pneumatic door wheezed behind me, cutting off his rasping laugh.

Fifteen miles later, when I drove by the Mt. Holiness Baptist, my mother's old Buick was parked under that tall maple with a fall raveling of brown vines. She was sweeping or dusting or scraping chewing gum off the bottom of the pews with a paring knife. She got paid $100 a month to be the sextant, but she would have done it for nothing. It was just her excuse for being at the church all the time, where she felt comforted and clear. There on the hill beside the cemetery, close to my Daddy's grave and her sister Nettie May's mound, where the brown grass was brittled frost every morning.

When I was young and smart-struck with myself, I used to watch her trancified and quivering with the Holy Ghost and think she was embarrassing and stupid, like something from Mars. After I got older, I came to see the church and the people buried there beside the church were the stones and mortar of her life's foundation. Moses and the Burning Bush and Lot looking back on Sodom and Gomorrah were just like sweet, familiar emblems of her only and best truths. Things she thought of every day just like some people always eat Grape Nuts or put a cup of Tide in the washer.

We don't go to church any more, me and Alice and the kids. We are just always off running. It pains my mother, but she doesn't say much, tell us she prays for us and that K-Mart owns our souls.

When I parked my pickup under the winesap tree, Buster came out of the barn, carrying a dead ground hog.

"He tunneling the crib?" I asked.

"Yessir."

"Glad you killed him, then."

We walked together toward the yellow light of the back porch. Some swallows dived the night light over the garage.

Inside, past the mud room and into the kitchen, I found Alice making instant mashed potatoes. Leander was watching TV. Molly was on the phone with Alfred, her mechanic boyfriend, who worked at Monte Frey's Chevrolet in Hoskins.

I kissed Alice on the neck.

"Hi, Moon. You have a good day, Sugar?"

I set the bottles down on the kitchen counter and got us two glasses.

"Fair to middlin', I guess. I dropped one of them windshields Custom Glass ships every Thursday. Told Randall, and he laughed, said that's why we got insurance."

"A toddy for the body," I said as I set her Seven-Up and vodka on the cabinet next to the stove.

"Thank you, kind sir," she said and took a sip.

I could tell she had already had a couple from somewhere, but I didn't mention it. Now Molly was crying in the hall, like she does when she and Alfred are on the phone and fighting about the rumors Molly keeps hearing about his other girlfriends he says he does not have. I have seen him myself with Claudia Skaggs, the dark-haired waitress at the Elks, them pawing each other in passing, but I don't tell Molly that.

"Maybe you two need a break from each other," I suggested two months back.

She told me I just didn't understand. I admitted it was possible. I have long since quit trying to make sense of people and who they love or don't. Love, it seems to me, is a death-defying act, one toe in front of the other on a tight rope always moving.

By seven o'clock, when the meat loaf was done, Alice was weaving a little as she carried the bowls into the kitchen. Leander came in and set the table, stopping to tousle my hair. Molly slammed the phone down and ran upstairs.

Bobby Fisk went by on the road outside with his yellow state truck and blew his horn. He and Larraine would be coming by later to play cards like they did every Thursday.

During the meal, Leander ate smidgens and played with her food.

She told us she won the seventh grade spelling bee and would go to Hoskins for the county spell down. Buster ate two full platefuls and asked if he could go over to the Haber Barn and shoot around with some of the junior varsity.

He was at the door when Alice called out to him.

"You be careful, Buster. Josh Wayneright drives 80 on that road going over past Haber's.

"Yes, ma'am. I always pull over and let him by."

Alice nibbled on a piece of meat loaf. I poured us both another double and took the Courier Journal into the living room where I could glance at the headlines and watch the news. After I got the latest scoop on who was axe murdering who in New York City, I pulled on my coveralls and went out to feed the hogs and check to see if the Duroc sow had killed any of her pigs. Uncle Lon said he'd had a Duroc sow who ate two of her own.

Then I smoked a cigarette and sucked on a Certs as I took the corn row behind the barn down along the squirrel slough and across the ridge on a footpath to my mother's trailer.

"You get the church cleaned?" I asked her, slipping through the weather stripped door quickly so as not to let out the heat.

"It'll do in a pinch," she told me with a smile, looking out over the top half of her bifocals.

She fixed some fresh coffee while I went out and cleaned the cables on her battery. I came in, and we talked about piddling stuff: her varicose veins, Doe Pop Skaggs' car wreck down near Delbertson's Branch on the old Levee Road.

"Natalie Spivey worked rescue that night, and she said he smelled like whisky," my mother reported, her eyes narrowed to a half slit.

"Wouldn't be Doe Pop if he didn't," I said.

"That don't make it right, though, does it?"

"No, Ma'am."

Then, before I could leave, she wanted me to pray with her. So I got down on one knee next to that old brown couch, propped up on one corner with a cement block. I listened to her whispering to herself. She asked God to bless the widows and orphans and our boys on foreign soil. I felt a pain in my knee and watched a cockroach run into a crack where a tile was loose on the floor.

Walking back across the fields, I could smell some cold weather coming.

I heard a coon dog over on Piney Ridge. Must be the Loney boys. Nobody else that big a fool or so anxious to stay away from home. I hunted with them once, two years before, and I excused myself away when they started talking about things they did in Vietnam, things they saw. Donald, the oldest, bragging about his string of Gook ears he brought back and kept in a foot locker in the barn.

Back at home, I fixed myself a triple and saw bubbles in my bottle. That meant Alice had been drinking out of my bottle and filling it back with water. It was an old trick.

I heard someone crying in the back bedroom.

"It's Leander," Alice told me, coming out of the hall, her eyes a little glazed.

"She told us about the spelling bee. She didn't tell us about this."

She handed me a note from the principal. Leander had stabbed a girl in the hand with a pencil and stolen $5 from another girl's locker. The principal wanted a conference on the following Tuesday.

"What the hell?" I wondered half out loud.

Alice worked her fingers back through her hair. She was wheezing a little. She poured herself a half and half.

"Having kids just doesn't make much sense sometimes, Moon Man," she told me and shook her head, then wandered off in to the television.

I stood there, jiggling the ice cubes in my glass. I guess I have been Moon Man to half the county since my senior year when I slammed five break away dunks in a tournament game against Bremen. But it still sounds funny when my wife says it.

Bobby and Larraine came over about 8:40. Bobby brought a 12-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon and left it on the back porch to stay cold. Larraine sipped a beer and fidgeted like a bird.

Alice hid her bottle back in the pantry and went back there two or three times an hour for crackers or chips or bean dip.

Sometimes, coming home at night, I will think to myself that somewhere things have gone all wrong. There must be a better way for things to go. So I will stop by Toby's and get a six-pack and tell myself Alice can drink three and I will drink three and we will turn in early.

But then things go all sour.

Alice gets tense and starts arguing with the girls about cleaning their rooms. She starts sniping at Buster about his girlfriend or carrying out the garbage. Or maybe she will just go down in the basement and sit there in that old busted lounge chair, saying I don't love her since she has gained weight or, worst still, sitting there, looking through the wall, all the way to the Neptune, lost in a brown study.

Next thing we know, she is rooting in her coat for her car keys.

"I need to run to the IGA for cigarettes," she will say, handing us that fake smile.

Half an hour later, she will come cruising back in, all giddy with apologies and hugs for everyone. Nobody has got to tell me there is a quart of vodka buried under some oily rags out in the utility shed, and I am not surprised when Alice has to find three or four reasons that night to slip outside and check on Beluah and the new pups.

By 10:15, Bobby and Larraine were ahead $8 in poker, and Alice was bumping into things. Leander came in to get a drink of water and tell everybody good night.

When she got to Alice, her mother hugged her tight and kissed her on the neck.

"This is my baby, my spelling bee girl," she said too loud.

"Quit it, Mom," Leander said, pulling free, her face full of revulsion.

Bobby and Larraine laughed.

We switched to 500 Rummy. We talked and laughed about old times when we were newlyweds living in trailers down on Pigeon Creek, where the pipes froze every winter and the coyotes knocked over the garbage cans.

Alice picked up her glass and shook it at me.

"I need some service here, Mr. Moon Man," she said, giggling.

I bowed and went into the kitchen, where I fixed her a watered down drink and mainlined myself two quick shots. I felt something hard and heavy in my gut, something like anger or fear, something I couldn't put words to.

About 11:00, Bobby and Alice wandered off into the pantry where she was going to show him how to make a new kind of shrimp dip. I talked loud to Larraine about Rico Burns' new Chevy, trying to cover up that loud silence in the kitchen. I guess maybe they were kissing each other, whispering and giggling.

Twenty years ago, she was a cheerleader, and she has never got over being middle aged and ignored by check out boys who call her "Ma'am."

Men watched her walk down the halls back then, and they stuttered when they talked to her.

Maybe she and Bobby were whispering about sneaking off to Mortonsville some weekend, the kind of thing drunk people say to each other when they are trying to lose something or find something.

Around midnight, Larraine led Bobby off in a staggering shuffle toward the pickup. He was singing dirty songs he learned in the Marines. Buster drove up just then and helped her wrestle Bobby into the cab.

Buster and I stood and watched them back out and drive away. Buster shook his head and went inside. I started up the porch steps and tripped and barked my shin. Sat there for a while, watching the dark formless figures of farm machinery in the back lot under the pale light of the night light.

Back inside, Alice was laying on the couch. The kids were all in bed. I sat down in the Hide-Away lounge, meaning to watch the local news. Somebody was burning cats in the cemetery in the next county. Next thing I know, I woke up, my mouth full of cotton and my head my fuzzy and swirling.

There was an old movie with Joan Crawford on the TV.

Alice was snoring: loud, adenoidal, drunken snoring.

I turned off the lights in the kitchen and saw the clock: 2:34.

I stood there a moment, leaning against the door, looking down at her. She had come to me 20 years before, a Pentecostal girl full of dreams, sweet like peaches on the tongue.

I wanted to wake her now. I wanted to take her in my arms and tell her it was not true we were all dreamed out. That we would start over again and get everything straight this time.

"Alice," I would begin, "How can I tell you..."

Then I heard Leander crying out in her sleep. I tip-toed in and touched her hair. She was wrestled wild in her blankets, battling what demons I could not guess. Whimpering like something scared.

"It's okay, Baby," I said, sitting down, hugging her to me. "Everything is okay."