|

|

| Jan/Feb 2011 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Jan/Feb 2011 • Nonfiction |

It's a mighty fur piece between New York and California. And, as Saul Steinberg's classic New Yorker cover demonstrated for us New Yorkers so long ago, there is that seemingly impassable chasm to traverse between the Hudson River and the rest of this nation.

So, the spring after we had packed up and left our upstate comforts behind at Hamilton College, we felt blessed when my scholar husband managed to snag the D. H. Lawrence Fellowship as a Writer In Residence in Taos, New Mexico. With this summer grant, not only were we provided a colorful literary detour in that "traumatic" crossing and endless journey, we were to be offered a modest stipend and a place for my husband to work on the Ranch.

What with our two young ones along with our huge, "countrified" poodle literally stuffed into the back of an over-loaded Plymouth wagon for days on end, the Fellowship would be a welcome pause as we plowed our way out to the Coast, and even something of a liberation. So we headed Southwest on the double.

My young husband had not only recently completed a doctoral dissertation on the work of that eminent writer, but since he had already launched himself as a published poet and short story writer, his credentials for the fellowship were deemed tailor-made. I might just add that this was merely the first of many such jaunts into exotic territory which that artist was to grant us over the years!

D. H. Lawrence himself had, of course, been long dead by the early '60s when we journeyed to the West, but the British writer had spent the better part of his brief life in foreign parts. Among them, scattered over the world, were Italy, Sardinia, Mexico, Australia, Ceylon, the South of France, as well as the United States. In fact, throughout his evolving career in writing, his works focused on these distant cultures in which he had traveled and lived.

While here in the States, it was mostly at this New Mexico Ranch where he felt himself at home enough to work. Here it was that he'd been able to pursue his last novel about Mexico, The Plumed Serpent, the very book that my husband's scholarship had centered upon.

Lawrence's two years in our country had come about oddly enough. And this is not to speak of his subsequent ownership of this ranch in such an isolated region above Taos! It would seem that back in 1921, an invitation from a perfect stranger had arrived for him back in England, from someone who'd read and admired excerpts she'd seen of his then forthcoming Sea and Sardinia in The Dial, a prominent literary magazine of the period. He was offered a welcome to the ranch and to "her" little town below it by the ambitious, imperious Mabel, neé Ganson, an heiress of a wealthy banker, who, in those early days impulsively sought to found her own literary Eden by surrounding herself with artistic celebrity. The lady's first marriage had left her already widowed at 23, and she was by then Mrs. Mabel Dodge, having next married a rich architect, Edwin Dodge, another union to end not very long after. Later still, there came her third and fourth, when she came to be known as Sterne and finally, Luhan.

The globetrotting Mabel had in the interim already purchased a Medici villa for herself near Florence, Italy, where she had busily entertained everyone of rank and importance, as well as a host of scandalous other luminaries of the period like Margaret Sanger, Emma Goldman, Lincoln Stephens, John Reed, and Big Bill Haywood.

By 1912, and already estranged from her third husband, she impetuously decamped back to America, to New York and Provincetown, in order to rejoin her artistic, radical friends and further establish her Bohemian credentials with her openly outspoken displays of bisexual behavior in New York's own Greenwich Village.

Also to her credit is Provincetown's initial association with the very notion of Bohemianism. And this distinction, she followed by yet another: her inauguration and mounting of major European and Modern works of Art at the Armory Auditorium in upper Manhattan, an annual show and major event to this day!

At its first opening, the story goes, she even sponsored the publication and distribution of a pamphlet commissioned from her Bohemian friend, Gertrude Stein. Its purported aim was to accompany the work shown, though it did not concern itself much with the art in it. Called, "Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia," it offered instead a self-promoting discussion of the lady herself, which was to earn the heiress further notoriety.

But it was in her very next escapade to San Francisco that the restless Mabel made her discovery of that sleepy little pueblo village below the remote Sangre de Christo mountain region of New Mexico, then little known and less visited. This promptly inspired her to found there her ideal society, and to attract to her colony a choice of poets, artists, and intellectuals, luring them to settle and surround her with the culture of which she had always dreamed.

Thus her invitation found its way to the distinguished novelist, D. H. Lawrence. Yet, it was not until he and his wife were returning from an extended stay in Australia in 1923 that they would accept her hospitality. He and Frieda came merely for a short interlude of rest. Still, what they found was an enchanting environment, an unknown landscape, one wholly new.

The Lawrences were captivated, taking to the wildness of that Western country at once. The Ranch, some 7000 feet up in altitude, made breathing at that level something of a chore, especially for the frail Lawrence. But the air was divinity itself, while the open spaces and the views astonished these Europeans and city people. The Lawrences stayed on and on, succumbing altogether, and were to be won over, despite all the persistent shenanigans of their overbearing hostess. And, it was then, in her eagerness to keep the writer in her orbit, or so goes the local lore, that the heiress made her extraordinary offer to make the Ranch theirs, in exchange for the manuscript of his already much admired novel, Sons and Lovers.

Our own arrival there, many years after these events, was not so very different, for we, too, felt those magical effects. Lawrence's Ranch, so removed, so etherial, was after all virtually unchanged and remained high up there for us to enjoy. We felt we had arrived: The West had shown itself to us, instantly, gloriously, and with all its finest fixings on display, just as promised.

Once upon a time on the flat lands below, the land had served as an Indian Pueblo. It had been settled as early as 1615, and soon was to undergo attacks from battling Comanche. Natives were also to fight off the onslaughts of Spanish conquerors, who were followed by the fanatically devout missionary Christians brothers. Even later, ambitious Confederate soldiers would battle over that same territory when Kit Carson sought to fend off the forces then dividing the Union.

Our own impressions quickly cascaded in. We gazed upon that landscape in awe, at its openness and almost empty magnificence, blinking in the extraordinary light. The very vastness of its design could stagger any Easterner's imagination. Each vista more huge than what came before, with gigantic rocks, monster clouds, and brilliant panoramas at sunrise and sunset. And, all of it smacked of what once was upon our continent: a raw, emerging nation, almost limitless in scope! The spectacle brought forth for us that sense of a frontier, as it might have appeared to our early settlers with its then endless seeming land mass stretching out American opportunity, not just as far as the Pacific, but as far away as the Asian horizons!

As our old Plymouth wagon chugged its way up the steep dirt roads towards the Lawrence property at Questa, some 20 miles north of Taos township, we noted how the atmosphere thinned and how our breathing came with greater difficulty. I quickly urged the children to take deeper breaths and watched them closely as they coped with that altitude change. Arrived, we were at a vast, splendid height, with remarkable vistas to every side of us.

Immediately calling upon the Ranch Caretaker to welcome us, we found him settled in a fine, large house. It was the house built after the writer's stay and the one lived in by his widow during the years following the death of her eminent husband. She had returned with Lawrence's ashes, and she was to reside in that house comfortably along with a third husband, Angelo Ravagli, during the later period.

Yet, that summer, we "grantees" were instantly escorted by our gentleman Caretaker down a dirt road some distance away from it to our own shabby quarters, there to find a tiny enclosure with a garden of sorts inside it, securely fenced in and fastened by a front gate. Above its entry a newly-carved wooden sign was to be seen which read, "The D.H. Lawrence Fellow," and that followed by my husband's name, elegantly whittled into it.

Close beyond it, we looked upon a shabby, patched up and plastered cabin with a makeshift tin roof, upon whose walls were to be seen a series of free-style, faded frescoes of huge, fierce bulls forging across that land, painted, some said, by D. H. Lawrence himself, so many years back. And, when that structure was unlocked for us, it revealed one sprawling room, bare but for the four cots now filling it, and they, covered by worn army blankets, together with flattened, yellowed pillows resting upon them.

This cabin indeed dated from Lawrence's days at the Ranch and stood that day virtually as it had back in the '20s—primitive, unaltered, and unimproved. And apparently, the D.H. Lawrence Fellow was to occupy it, family and all! We could only suppose that its once magic atmosphere was to inspire his own creations.

Over in a far corner, we noted some additional fittings that had, at some point, been added to accommodate an electric hotplate. And below this, some space made to hold an assortment of plastic plates, cups, and implements. A sink had been set nearby, too, which seemed to be running hot as well as cold water. And nearby that was a little water closet with a primitive facility enclosed.

Inconsequential were our family's numbers, and of no concern to our Caretaker host, who hardly noticed our dismay while he swiftly displayed these provisions. His matter of fact tone asserted his own view: "What more could we need?"

So that was that. After this curt schpiel inside the cabin, our host concluded by adding "only a few minor details" before leaving us to make ourselves at home there. These minor "limits," as he phrased them, need "to be maintained at all times." It was then that he stunned us with:

THE DOG MUST BE KEPT ON A LEAD

CHILDREN ATTENDED AT ALL TIMES

NO WANDERING AROUND THE RANCH

and finally,

BEFORE ALL RANCH EXCURSIONS CONSULT OFFICE

Concluding with an offer to answer any further questions that might come up for us, he promptly took his leave.

While the children ran round the room, my husband and I stared at one another. "Any questions?" we chorused, in some despair.

Was this then to be our grand introduction to freedom in the WILD WEST? Our liberating exposure to the wide expanses, those stretches of natural wonders spreading out before us? Were we to be living in one room, enclosed in a pen on the Lawrence Ranch? Had we then, come all this distance to be so interned while at the same time on display for the gaping and curious, the D.H. Lawrence groupies scheduled to be appearing all that summer long? We stood together helpless that moment and smarted at the very audacity, the impertinence of it!

Had we voyaged so far for such a reception? Hardly! We'd visualized another life, picturesque and all new. Certainly, this regimen bore no resemblance to what we'd described and promised our adventurous, imaginative children. We had assured them that there were horses to ride, trails to follow, wondrous wilderness to explore at leisure, all of nature at their beck and call.

Then, too, consider the fate of our "Chien Royal" poodle, a regal animal, who'd not been tethered in all his adult years up at Hamilton College campus back east, and who could now barely recognize the need. Crossing the country, he'd shown just how well he comprehended any hazard around his family by his protectiveness and demonstrated how faithfully he obeyed urgent commands whenever they were issued. Now, that country nose of his directed every action, alerting him to danger. And with so many unfamiliar odors surrounding him, he was busier than ever making his investigations into the new circumstances.

My husband certainly did try to improve the situation, first by going directly back to our Caretaker to discuss other alternatives for housing. But his pleas proved to no avail. Nor could this gentleman imagine what the "difficulties" might be! Certainly, he had no intention of displacing himself from the main house for our sake; that had been clear from the start.

Telephoning the University of New Mexico's chief administrator down in Albuquerque was next, with another appeal to him. From that response, he comprehended the situation: Since his Caretaker maintained the Ranch for the University right through the brutal winters there, he could not afford to challenge any decision of his, nor would he intervene in this recent one. "We are confident that you will manage, young man," was his conclusion, "and will work happily up in that magnificent atmosphere."

There seemed little choice, so we tried! In those first days we worked to make do, to settle in, asking one another, "Were we not, after all, in God's country? Sitting high in the sky, where the air and the light were bewitching, and genius had once flourished?" Surely, we could flourish as well.

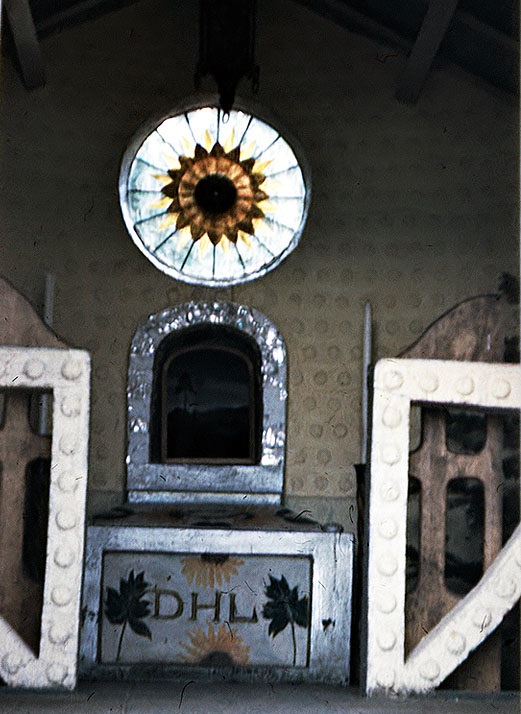

So after we had unpacked, squeezed all of us into that sparse, rundown cabin, bought some groceries and extra fittings, and even managed to get a decent meal fixed there, we soon began to investigate our surroundings. We visited the graves of the writer and his wife, Freida, just up on the hill from our cabin, and sat silently for a time in the little Spanish-style chapel above these which had been built not only to enclose his remains but to commemorate the writer's life at the Ranch. Inside it was to be seen the altar with the initials D H L carved large in the white stone. And over that sat an arched inset, decorated with superbly crafted aluminum work which on that day gleamed with the incoming sunshine. All was quiet around that memorial.

Beside the altarpiece sat the writer's own New Mexican homespun denim shirt, still there, his festive cowboy hat along with Lawrence's huge old typewriter (as though ready to sample). Indeed, sitting inside that curious shrine, with its Phoenix on the roof and huge crucifix marking his wife's grave outside, we did sense his enormous presence, that overpowering force so much a part of his literary work.

In those first days, we scouted about us as well for those settings where Lawrence had labored and was said to have created scenes for works which were deemed among his finest. We and our children lounged under the tree he had chosen as his favorite and in the grove he had found most attractive.

Then, too, it was exciting for us at first to travel down from the Ranch to the flats, to seek out the Pueblo with its tribe of Taos Indians, peoples whose ancestors had lived in that valley long before Columbus had ever set foot on our shores! Settled they had been even before Europe had emerged from its dark ages. And to gaze, for the first time, upon a village made entirely of adobe—which we soon learned was merely earth mixed with straw and formed into sun-dried bricks, then to be constructed into early apartment style dwellings, built side-by-side, and serving many separate occupants all together—was awesome to behold.

Close by stood the community's San Geronimo Chapel, built back in 1850, a structure which was already a replacement for an earlier one yet. In the early years of 17th Century, the Spanish Conquistadors had stormed through it, devastating whatever was in their path, and it was later only that they were to be followed by their missionary brothers then aiming to make good Catholics of their "heathen" neighbors in the new world.

By the time we'd trooped through the nearby town of Taos and surveyed its surrounding hills, there was little left for us but to get on with the main purpose of our residence there. My husband needed to find a good place for himself to work and to get at it immediately, while the children and I would somehow have to manage by occupying ourselves without disturbing his concentration.

I began to think of ways to amuse the children and keep them quiet and occupied. But as we idled about the Ranch, we were in trouble before we half-tried, given all the Caretaker's stipulations. And there seemed little for it but to get ourselves out of the way.

The simplest solution I could come up with was to drive them down to Taos daily. There I found a little nursery school operated by some enthusiastic local mothers and teachers, and where, in company of other children, they could frolick and run free.

A demanding routine that proved! What with getting the groceries up to the ranch, managing their daily lunches, meeting the endless schedules for their delivery, transport and pick-up, my own days resembled a frantic City life far more than the Western expanses we now reveled in.

So my husband and I soon arrived at a drastic decision. This was hardly the life we had sought. Indeed, especially not here in this open country. Nor could we stay put for such constraints over the long summer months. And since our modest stipend was already in our hands, we were free agents, after all, and could go our own way. In truth, the only commitment to the Foundation my husband was actually bound to was the delivery of a lecture on Lawrence's great contribution to the literary world, and this talk was scheduled to be presented at the University of New Mexico campus, down in Albuquerque. Most certainly, my husband planned to honor that obligation, to stay in the vicinity while he wrote and then delivered this lecture.

So in the interim, we were most certainly at liberty to seek out quarters for ourselves. Lodgings which did not dispirit us or restrict our own or our children's movements in the process. And, as long as the money lasted, this is precisely what we planned to do with ourselves.

So we packed up yet again and headed down to Taos to check ourselves into their Inn, where we found comfortable, separate rooms we could sleep in and even a fine swimming pool, set in their ample garden area to add to the package.

Yet, word had already spread in this minute village. Almost immediately our defection had become the talk of the town! Was it possible? The Lawrence Fellow had simply walked out of his post at the Ranch? That he and his family were staying in the Village, like ordinary tourists? And even more scandalous: that the year's recipient was now altogether without proper working space for his writing?

We were, at this point, very little aware of such erupting gossip, less still of the persistence of Taos' warring Writers' foundations surrounding us and their long-standing quarrels. Yet its force could fan revolutions, and suddenly we were thrust into the very heart of them.

Curiously, however, rescue did come, and from a completely surprising source. Before we knew it, we found ourselves summoned to visit with the elderly scion of the world-renowned Wurlitzer Organ Company fortune and now the senior executor of its Foundation. A long-term cultural venture, it was based in Taos and had been founded to provide artists—not only in music—but those working in every other artistic discipline as well, with stipends and housing facilities for periods of time, uninterrupted by financial concerns. Wurlitzer aimed to make possibilities for such artists to concentrate upon their art year-round.

And, it was this very lady, Madame Helene Wurlitzer, who now invited us to her mansion, located just near the main square of Taos. Her hospitality on the occasion was perfection itself, with fine china and fresh-baked scones in the New Eastern style. This was accompanied by the genial small talk and the etiquette of her hospitality. So all proceeded for a long while. Talk went of the beauty of her surroundings and the fine quality of Taos' air.

Soon enough, however, came the proper moment for her inquiries into our present state of affairs. And, there was little hesitation in responding to her query, for we were eager enough to tell of those current woes. We spoke candidly of the "insensitive" Caretaker up at the Lawrence Ranch. She attended all the while and to every single detail, clearly much intrigued to learn such circumstances. She greeted them, in truth, with considerable relish!

We explained how, after our try up there, we had found the regimen virtually unmanageable, certainly not in the cramped one-room lodging he had chosen to squeeze us into, adding only that we had had no choice but to abandon the glorious Ranch grounds altogether.

The expression upon the great lady's face was eloquent: her "competitor Foundation" had just been deserted by their year's grantee! Indubitably, she foresaw a thunderous scandal for this tiny community.

"Would you then, young man, welcome other means to stay on here in Taos?" was her immediate query. My husband's unqualified, enthusiastic assent had her instant attention. And before we knew it, she had called upon her Foundation's manager, Henry Sauerwein, Jr., to "find us such quarters, and to do so for that very night!" In short, she commanded, "to look to our every need."

Reveling in this situation, she delighted in the prompt procedures she alone could put into effect. Immediately after, she would make her claim to the "D.H. Lawrence Fellow" for that summer, transforming him for all concerned to a "Wurlitzer Foundation Grantee in Writing." And to prove it, she boasted of the spacious quarters in one of her Foundation's best houses that she had provided for us in Taos' village.

So before we knew it, we had quarters of Wurlitzer's own, with rooms for us all. The furnishings were spare and old, but entirely ample, and with the hardware store right there to supplement anything missing, there was no lack. My husband even had his light-filled study all to himself. We were content, the children were merry, even the dog was lighthearted, sniffing about freely and once again his own boss.

Settle we did, to stay for a productive two months. And it wasn't very long after that we found ourselves being approached by any number of colorful contributors to the Lawrence legend still living right there in the area. Remarkably, some of the principals from his own period were alive and very much a part of its cultural life as late as the early '60s.

Mabel Dodge Luhan herself still remained a vital presence in the community she alone had planned and cultivated. Unfortunately though, we were soon to learn that the now elderly heiress had been taken gravely ill shortly before our arrival there. She had been rushed to a hospital nearby, and reports came fast that she was failing steadily. She died not long after, and thus, we never did get the chance to meet her.

However, still remaining there, was the spirited Lady Dorothy Brett, a British aristocrat and painter, who had made her own way to Taos in the '20's with the Lawrences as they returned to the area, and in fact, she had never really left it since. By now, to be sure, Lady Brett was something of a doddery, and a very deaf old person, yet as chatty as ever and eager to recollect tales of her past life with her eminent friends, both here and back in England. Notably equipped with a huge earphone, which she carried about with her everywhere she appeared, she would haul it aloft, listen to each speaker, encouraging all to shout into her phone. Inevitably, this was followed by the chorusing of her constant refrain: "Eh, What was that you said, eh, eh? You will need to speak up, yes, louder, louder!"

Her stories of such early days remain memorable even now. How she loved to gossip over their initial arrival at the Ranch, and of the reception they received from the strong-willed, indefatigable, and ever-tenacious Mabel Dodge Luhan! She recollected Mabel's dogged attempts to rule their movements and even their lives, how this persisted not only over their first months up at the Ranch, but over the long years as well, even to those after the writer's death and the return of his widow carrying his ashes.

Freida Lawrence's return to Taos had come in 1934, four years after her husband's death in the South of France, where they had lived in his last days in hopes of recovering his health. Yet, by then she'd already made her future commitments to a new husband, Angelino Ravagli, an Italian, considerably younger than she, and still "married," as he accompanied her back to the Taos ranch, abandoning a wife and family back in Europe. Eager to leave Europe as soon as they could, she aimed to reclaim her property and her standing at the Ranch, as well as to transport Lawrence's ashes to the place he had loved so well.

The writer, of course, had already been interred, but he was now exhumed, cremated, and carried back to America, presumably at his own wish. Yet, exactly what transpired in the course of that trip remains in doubt to this day, and anecdotal versions came in different forms from the various witnesses we met during our stay there.

One story seemed to give everyone associated with the group a great guffaw. This, apparently happened on the way from Italy when the lady is said to have left the cylinder containing these ashes behind. Some claimed Freida had forgotten it at a friend's house, others insisted it was left abandoned on a train station platform. And scuttlebutt had it that the infatuated widow, Frieda von Richthofen-Lawrence-Ravagli, was simply too distracted to note that the ashes were missing until it was too late! A few went even further to add that this loss surely required some desperate replacement, to be made at some unknown stop, with the substitute of other ashes for Lawrence's own.

Such rumors concerning his burial persisted with further scandalous tidbits. We learned as well of Mabel Dodge Luhan's interference concerning the place where they were to be put. She objected to his being buried in that "that outhouse of a shrine" and had made her own, far grander plans for his interment below the Ranch with help from her Taos Indian husband, Tony Luhan. At the nearby pueblo, the pair had arranged an elaborate dancing ceremony to celebrate the departure of his great spirit. And, all of this only to be cancelled later by Frieda!

Ah, the outpourings, and the varieties of such recollections! After so many decades had already elapsed, to listen to the desperate reaches for celebrity, for notoriety, not to speak of the many recriminations and vilifications still active, was testimony to the endless claims made upon "genius." A memorable time it was, to be sure.

Madame Helene Wurlitzer, who so embraced us in rescue, also croaked away about her own vast efforts to bring chulchur of every artistic variety to "a then silent and barren land," chattering on about that early pueblo village of Taos as it then appeared to her. And several of her own remaining "grantees" added their eloquent recollections of such "old times" as well. Among them the influential painter Andrew Dasburg and her longtime Foundation's director, Henry Sauerwein, Jr., an articulate amateur historian of Taos himself, and an evocative teller of its many early visiting artists, like Georgia O'Keefe, for example.

Yet, can there be any who can better depict for us the Ranch at Taos as it once was, or describe it more vividly, than its "great spirit" himself, D. H. Lawrence? Back in Italy and already in failing health, he wrote longingly of it in Mornings in New Mexico:

I wonder if I am here, or if I am just going to bed at the Ranch. Perhaps looking in the Montgomery Ward's catalogue and drinking moonshine and hot water, since it is cold. Go out and look if the chickens are shut up warm: if the horses are in sight: if Susan the black cow, has gone to her nest among the trees, for the night. The cows don't eat much at night. But Susan will wander in the moon. The moon makes her uneasy. And the horses stamp around the cabins. In a cold like this, the stars snap like distant coyotes, beyond the moon. And you'll see the shadow of actual coyotes, going across the alfalfa field. And the pine-tries make little noise, sudden and stealthy, as if they were walking about. And the place heaves with ghosts. But when one had got used to one's own home-grown ghosts, be they never so many, and so potent, they are like one's own family, but nearer than the blood. It is the ghosts one misses the most, the ghosts there, of the Rocky Mountains, that never go beyond the timber and that linger, like the animal, round the spring-water. I know them, they know me; we go well together. But they reproach me for going away. They are resentful too.

Even now I can contemplate that bucolic, Arcadian scene as we found it then, and it remains stirring. Alas, when we were to return to visit there during the early '90s, it seemed hardly visible at all. All those many "improvements," the new structures, the long concrete path built up the hill towards Lawrence's Memorial Chapel, now so well-trod by the thousands of streaming visitors trekking up and inside the Chapel for a look. Long gone is that peaceful, isolated setting, along with his snazzy cowboy hat, denim shirt, and wonderful old Remington.

Today, his Ranch is just another tourist attraction.